Welcome to Part Four of Bama Confidential, a week-long series that goes deep into the past and present of Greek Life at the University of Alabama. If you missed Part One — on sorority rush — or just want to read the intro to the series, and how it found its way to Culture Study, you can find it here. You can read Part Two, on The Machine, here, and you can read Part Three, on how the Greek System stayed segregated until 2013 (!!!) here. If you want to explore the content coming out of #Rushtok this week, I’m curating it over on my Instagram (and make sure and check the pinned stories). Regular Culture Study Readers: This series will arrive in your inbox every morning this week. If it’s not your thing, don’t worry, we’ll be back to regular Culture Study programming next Sunday. If you’re not a Culture Study subscriber but want to make sure you don’t miss the next installments, just sign-up below. A few months into the reporting for this series, we received an email from the Pi Kappa Alpha (Pike) fraternity:

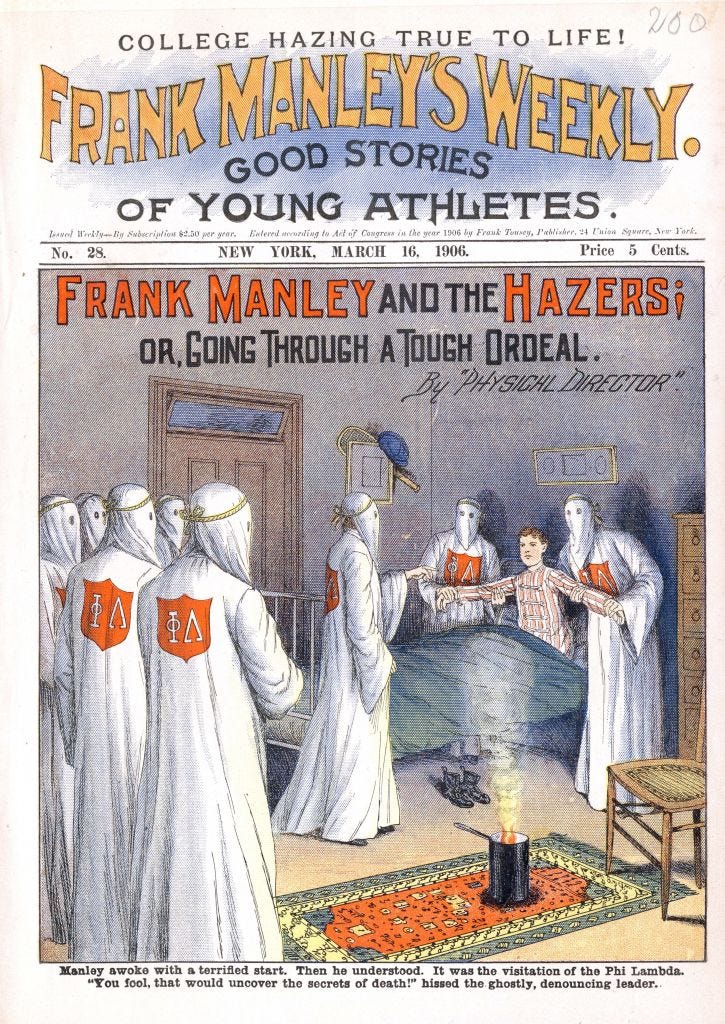

That email is silly, right? Not only does it openly admit to a code of silence, it shows the childish self-righteousness they have about it. But it also underscores what you bump up against when you try and report on fraternities at UA. Secrecy is kind of the point of this entire series, and though we often managed to puncture that secrecy, we also crashed into a bunch of dead ends. An email like the one above ostensibly gives us nothing — but it also reinforces just how pervasive (and oddly, open) the secrecy is. Still, it’s hard when unanswered questions are at the heart of your story. Questions like what happened at Pike one night in the fall of 2022 that prompted the suspension of several members and eviction from the fraternity house? That’s what the email to them was regarding — what we were trying to get answers to. All that’s been publicly confirmed is that the suspensions arose from “standards violations” and that the decision was handed down from the national fraternity (as opposed to the university). It’s unclear what those standards were, or how they’d been violated. Talking to students on campus, I heard wild rumors, which I won’t repeat here since they’re unsubstantiated (hence the email to Pike). We submitted an Official Open Records Request to UA for emails and other documents. After about two months of following up with them, they finally responded to just one of the seven items we requested (concerning the school’s contract with Navex, the outside company that runs the hazing hotline). They’ve yet to respond with the other information we’d requested. So we started doing what any journalist does in a situation like this: we tried to get just one person to talk. We reached out to current fraternity members and recent graduates. We DM’ed on Instagram and TikTok and priority messaged on LinkedIn. We found campus email addresses and phone numbers. All in all, we reached out to several hundred current and former Pike members. And we got…basically nothing. Which, again, is the story. In the past, I’ve struggled to get people to agree to an interview on touchy or potentially scandalous subject — but I’ve always eventually found someone willing to talk. This — this was different. A few guys gave us one short conversation before ghosting us entirely. Most just didn't reply. This total stonewalling was fascinating. No one would say as much, but it was clear that members had been told to ignore all interview requests, no matter what we said we wanted to talk about. Even Pike alumni — grown adults with much bigger things to worry about — wouldn’t break the code of silence. Something clearly happened in the fraternity house that night. But Pike has figured out a way to make sure no one — apart from their members, and maybe not even all of them — knows what. Silence creates conditions for power to reproduce itself. If no one talks, no one can question what’s happening behind those closed doors. But sometimes, you do find out what happens inside. Because sometimes… there’s a lawsuit. ● If the guys have it much easier than the girls during Rush, the opposite is true for the next step in the Greek initiation process. “Pledging” — or “new member education period,” as it’s officially called — is like a trial membership period. It’s when the active members get to see if you have what it takes, and how badly you want to join. And in contrast to Rush, it is decidedly unchill. At Bama, pledging would sometimes last for months, or even a full semester. It lasted so long, in fact, that eventually the university stepped in and put an official cap on pledging: eight weeks. That’s on top of the university’s policy that bans all forms of hazing, although pretty much every fraternity still practices some form of it, so who knows how effective this time limit is. A lot of it is physically harmless — even if almost all of it is physically coerced. But some of it is harmful. Because for the men in Greek Life, proving your loyalty can require going to extreme lengths. Based on the timing of the Pike suspensions, it seems likely that they were related to hazing — which helps explain the intense secrecy around it. Again, we don’t know what happened there, but we did finally get someone to talk to us more generally about what hazing at Bama is like — although he agreed to talk to us only under certain conditions. “I would say, based on the definition of being forced to do something that you don't wanna do, we were hazed 24 hours a day for 12 weeks,” says Luke, an alum and one of the only Bama fraternity brothers — out of hundreds and hundreds we reached out to — who was willing to broach the subject. “It's a huge, huge part of the fraternity culture,” he said. He also wasn’t at all surprised that we couldn’t find any current students to talk. “It would be like an explicit betrayal. They're in it. It's their whole life.”

I said he would only speak to us on certain conditions, so I should be clear that “Luke” isn’t his real name. He agreed to tell us about his experience so long as we didn’t use any identifying characteristics, so I also can’t tell you which fraternity he was a part of Bama, nor exactly what year he graduated. But I am allowed to say it was about a decade ago — which is notable because despite all those intervening years, Luke is still nervous about speaking out. It goes to show just how effective the system is at imposing secrecy. But back to the coercion: Knowing that fraternities often surprise pledges with events or tasks in the middle of the night, Luke says he spent months sleeping every night in his “pledge uniform” — Levi 505 blue jeans, New Balances, a tucked-in polo shirt, brown belt, and white undershirt. (I’ll let that outfit speak for itself, but you can also see it on display in the TikTok videos of current pledges, who are tasked with creating dances like sorority girls and posting them). Luke also slept with his phone on his chest every night in case a fraternity brother called him. This sounds like a pretty terrible way to spend three months, but also pretty basic power shit: you’re told what to do and you do it, over and over and over again. As are other pledging activities we heard about: cutting up a $1 bill into a hundred pieces and forcing pledges to tape it back together; sending pledges to the quad to catch a squirrel; delegating all setting up and cleaning up duties around fraternity parties to pledges. Weird, but I can see how, particularly in hindsight, you might come to see it as a twisted sort of fun.

“It's the best time you never wanna have again,” is how it was described to Luke — and how he described it to me. It’s part of the legend that you kinda have to buy into if you want to be a member of the club. Fraternities even allow some of this stuff to happen out in the open (like in the dance TikToks) because it's a good branding exercise. It’s also a way to make people look over there, at the pledges being ridiculous in public, and understand that as the extent of their hazing — not everything that goes on behind clothes doors. Which brings us back to the lawsuit. The lawsuit didn’t involve Pike, but it did focus on another Old Row, top tier UA fraternity: Sigma Alpha Epsilon, or SAE (which was actually founded at the University of Alabama, back in 1856.) It’s a reasonable analogue, and probably the closest we’ll get, unless any lawsuits arise from that Fall 2022 incident. The details of this case are pretty awful, so we’re not going to discuss it all. But here’s the broad strokes laid out in the lawsuit itself, which was originally filed in September 2023: It involved an SAE pledge named “HB” — that’s how he’s identified in the court filing, since he was a minor at the time of the incident — who was a freshman at Bama. And I know, based on conversations with his lawyer, that HB had been accepted into Harvard, but chose to attend the University of Alabama because he was offered a full ride. So you can probably picture this guy. New to campus. Wanting like every other student to just fit in, to make friends. The lawsuit alleges that during pledging, fraternity members ordered HB to snort a “white powdery substance.” HB refused, at which point a bunch of guys forced him to go into the house’s basement, where he was allegedly beaten in the head, stomach and torso. The lawsuit also tells us that while HB was being beaten, he was allegedly told that he was going to “die.” And it seems that he almost did: HB ended up at the hospital, having suffered a traumatic brain injury. (The lawsuit also says that after the beating, HB was allegedly forced into a kiddie pool where members demanded he shout racial slurs at Black students under threat of physical violence. According to the lawsuit, HB refused.) In a statement to Tuscaloosa station WBRC, SAE nationals said "acts of hazing and misconduct do not represent the Fraternity's values.” They noted that they don’t comment on matters related to litigation, but added that “members who engage in these activities will be held accountable to the fullest extent.” (A quick aside: In 2014, SAE officially eliminated their pledging process and instituted a new program called “The True Gentleman Experience.”) The SAE national organization has asked to be dismissed from the case, which is still ongoing. The UA chapter of SAE hasn't admitted to any wrongdoing in response to these claims. When we reached out to the University of Alabama about the lawsuit, they told us that students and student organizations must adhere to university policy, the Code of Student Conduct, and the state of Alabama law related to hazing. They also pointed us to the UA website, and resources that specifically address hazing prevention, like a hotline they’d set up to anonymously report hazing incidents. (When asked about the lawsuit, the IFC pointed us to the same resources). Though the university plasters the hazing hotline number on all the websites and literature connected to Greek Life, the students we spoke to said it’s considered a joke. There was no real way to keep anonymous, they might end up implicating themselves — plus, they said, as they’d already seen on campus, nothing would really change. According to a hazing database maintained by author, researcher, and Professor Hank Nuwer, in the last two decades, at least 70 fraternity members have died in hazing-related incidents while in college in the US. SAE – the fraternity HB was pledging – has an especially bad record. Over that same two decade time period, at least 10 members of SAE have died in hazing related incidents across the country. (We reached out to the SAE chapter at UA for comment and have yet to hear back.) This is part of the ritual humiliation and violence that thousands of men sign up to endure every year — some with more understanding of what’s going to happen than others. People who’ve gone through it will sometimes admit that it’s shitty, but they often follow up by insisting that it’s a crucial bonding exercise. It’s what makes them a brother. I get it; anyone who’s been through some form of trauma bonding gets it. But there are so many other ways for men to figure out how to develop trust and intimacy with one another. But no number of exposés has actually changed the culture of hazing within these organizations. If anything, it’s just been driven further underground. ● While the actual hazing rituals can vary greatly between houses and campuses, of those incidents that result in either lawsuits or police investigations, there are two mainstays: violence and alcohol.

While drinking is often one of the reasons people join fraternities, what we’re talking about is stuff that goes way beyond normal partying. Luke told us about one particular challenge — the “Tall Boy Challenge” — where pledges have to finish a six-pack of 24oz beers in thirty minutes. (“I don't know if it sounds fun,” he said, but “it's not fun.”) Most pledges throw up, often more than once. You boot, and then you rally. And that’s just step one. Step two is being lined up and given a “handle” of whiskey — a 1.75 Liter bottle — that each has to drink from it and pass it on. It has to be empty by the end. People go along with it because there’s no straightforward way to opt out; the implicit and explicit message is that dropping out just puts more work on the shoulders of your fellow pledges. Or, as Luke put it, “you have to take a big pull because you can't let the next guy down.” Step three is attending a “swap” party with a sorority, where the super drunk pledges are paired with sorority pledges. “In some cases,” Luke said, “a pledge might be like implored” (not forced, Luke clarified for me, but implored) “to like slap a girl on the ass or motor boat her.” That amount of alcohol over such a short period of time is a disaster waiting to happen — for the guys, but also for the women. They’re not allowed to bring alcohol on sorority premises. But they, too, often join the Greek system for the party life, which means that they’re left trying to circumvent these rules, either by sneaking in liquor and taking a whole bunch of shots in quick succession before heading to an event. Or, in order to drink, they have to depend entirely on the fraternities to supply it. Which means that they’re drunk on guys’ home turf, in cavernous fraternity houses that are unfamiliar to them — spaces where the guys are treated like unaccountable monarchs. And if you’ve just done some shots before walking out the door, the effects are probably kicking in just as you arrive at the party. “Fraternity boys in general scared me,” said Emie Garrett, who we heard from back in the first article. Before attending her first fraternity party, Emie had it drilled into her: Never leave your drink with anybody. Watch the bartender make it. Emie says girls were taught to keep their hand over the top of their drinks at parties. Of course, a lot of this advice goes out the window once you show up to a party, a little tipsy, with a bunch of jacked dudes shouting at you to do shots. “I just had so many friends who were roofied by guys that they trusted,” Emie said. It never happened to her. But other girls told her about experiences where they blacked out on a night when they didn't drink much or woke up somewhere with no memory of getting there. They’d make excuses for the guys: I'm the one that went there. I’m the one that drank it or did whatever drugs. They’d brush it off, make a joke of it. Reporting it never even entered the conversation.

Most of the sorority women I spoke to voiced something similar. They’d sat in their houses and watched the presentations on how to report a sexual assault, and how to get someone out of a vulnerable situation — as if they were soldiers, readying for war. Then there were the meetings after the parties — the ones where Emie saw sisters get dragged into hearings over pictures they posted online where they looked too drunk or were too provocative. “It’s like female sexuality that they were policing,” she said. So many women have internalized the idea that if something happened at a fraternity house, it was their fault for putting themselves in the situation. And they knew — by watching others — what usually happened when you tried to speak out about it. And it was usually nothing but embarrassment and shame. “The way of thinking in fraternities,” one fraternity member told me, “is that you're invincible. Nothing's gonna happen.” To some extent, that’s true: most know just how far to take things before crossing the line into injury, or the sort of abuse that would make someone hire a lawyer. Nationals mostly look the other way — all they really care about is liability. Same for the university. But that sheen of invincibility doesn’t mean there aren’t hidden scars. Luke told us about something called “the line-up,” which, he said, is “the definition of hazing to most guys at Alabama.” The guys line up, and then they get yelled at by the active fraternity brothers. Shamed. Embarrassed. For hours. Sometimes all night. “It's extremely verbally abusive throughout. That's the tone. And then it gets, you know,” Luke said, his words catching slightly. “Well, it certainly gets physical at times.” Pledges were punched in the face and punched in the gut. Matches were put out on their skin. They had to plank with their elbows on upturned bottle caps, cutting into their flesh. They might be told to fight each other, bareknuckle. This doesn’t happen just once. It happens many times throughout pledging. And there’s always one guy who cops it worse than the rest. “It's absolutely…” Luke railed off, before finishing: “It's a nightmare. It's horrifying.”

Why put yourself through the hazing and embarrassment? The physical and emotional discomfort? “It's a gang. And we understand that,” Luke said. And if you refuse to play along? “Well, you can leave,” Saying “you can leave” makes it seem like it's all up to you. And yes, of course, technically you have a choice. But at 18 years old, desperate to make friends, in a scary (and sometimes hostile) environment under that amount of pressure, I don't think it really feels like you have a choice — especially not if you’re locked in a basement. ● In 2014, SAE banned pledgeship at a national level in order to discourage hazing. But of course, these organizations also understand that underage drinking is one of the ways they attract new members — and have struggled to find ways to police them. So they often appear to have firmly worded policies….and very little enforcement. When someone sues them, it’s easy to direct the blame to the individual students — they were the ones violating the rules. According to UA’s Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life, Bama’s chapter of SAE has violated university policy and received some form of penalty for six out of the last ten semesters. It’s unclear exactly what those penalties are — the "Greek Scorecards" that the office maintains list out general codes like “disciplinary probation” and “loss of privileges” — but we found no evidence that anyone had been suspended or evicted. (We reached out to the SAE chapter at UA for comment about all of these allegations and have yet to hear back.) Some fraternity members argue that hazing proves a pledge’s strength. But what it actually does is make a pledge vulnerable — not just during the hazing, but afterwards, too. The things they did, the things they saw, the things they didn’t stop from happening. Plus, as a fraternity member, you don’t just endure a year of hazing. The next year, you become the hazer. To talk about what happened would be to implicate yourself in the process. In this way, hazing functions as a sort of blackmail, contributing to your own kompromat and thus continually extending the curtain of secrecy around it.

This is how the power of secrecy reproduces itself within fraternities. And it’s why so many anti-hazing measures don't work very well — because they rely on people breaking that silence. It relies on people telling on not only their friends but themselves. It requires them to admit to their worst moments of abjection, and accounting for what they did when given power over others. It relies on them processing what it is they went through, and reckoning with what it was all for. It's a lot easier to just keep your mouth shut, convince yourself it was all in the name of brotherhood... and move on. Take the example of Luke. While his exact experiences aren’t universal across fraternities, they echo conversations I’ve had with so many of my fraternity peers. Despite undergoing months of forced servitude and nights of “horrifying” treatment, Luke loved being in his fraternity. He thinks pledging does make you feel like you’re more bound to something larger than yourself. Crucially, he said if he had to do it all over again, he absolutely would. Which, again, is why it’s so hard to get people to talk about all of this. It’s a feedback loop. You join a fraternity to feel part of a club. Being part of the club means doing something you might not otherwise ever do. You keep it a secret so you don't get in trouble. Keeping it secret makes you feel more like part of the club. When we first started putting this series together, part of me didn’t even want to talk about fraternities — because I knew we’d have to tell so much of the same story about hazing that so many have before, to so little effect. We know hazing kills people. We know it’s coercive abuse. But enough people have come to understand it as a central to their identity within Greek life — central to their power — that the tradition, shitty as it is, will not end. That’s what I’ve come to believe about fraternities: so long as they exist, so, too, will some form of hazing. It’s at the heart of their understanding of themselves: as masculine dudes’ dudes, sure, but also as the next generation of power brokers, who then protect the generations that come after. No wonder The Machine seems to think it can act with impunity — it acts like an Avengers group of Greek members. And their power, as you’ll find out, is by no means limited to their four years on campus. ● Catch-up on what you’ve missed with Part One: Part Two: Part Three: |