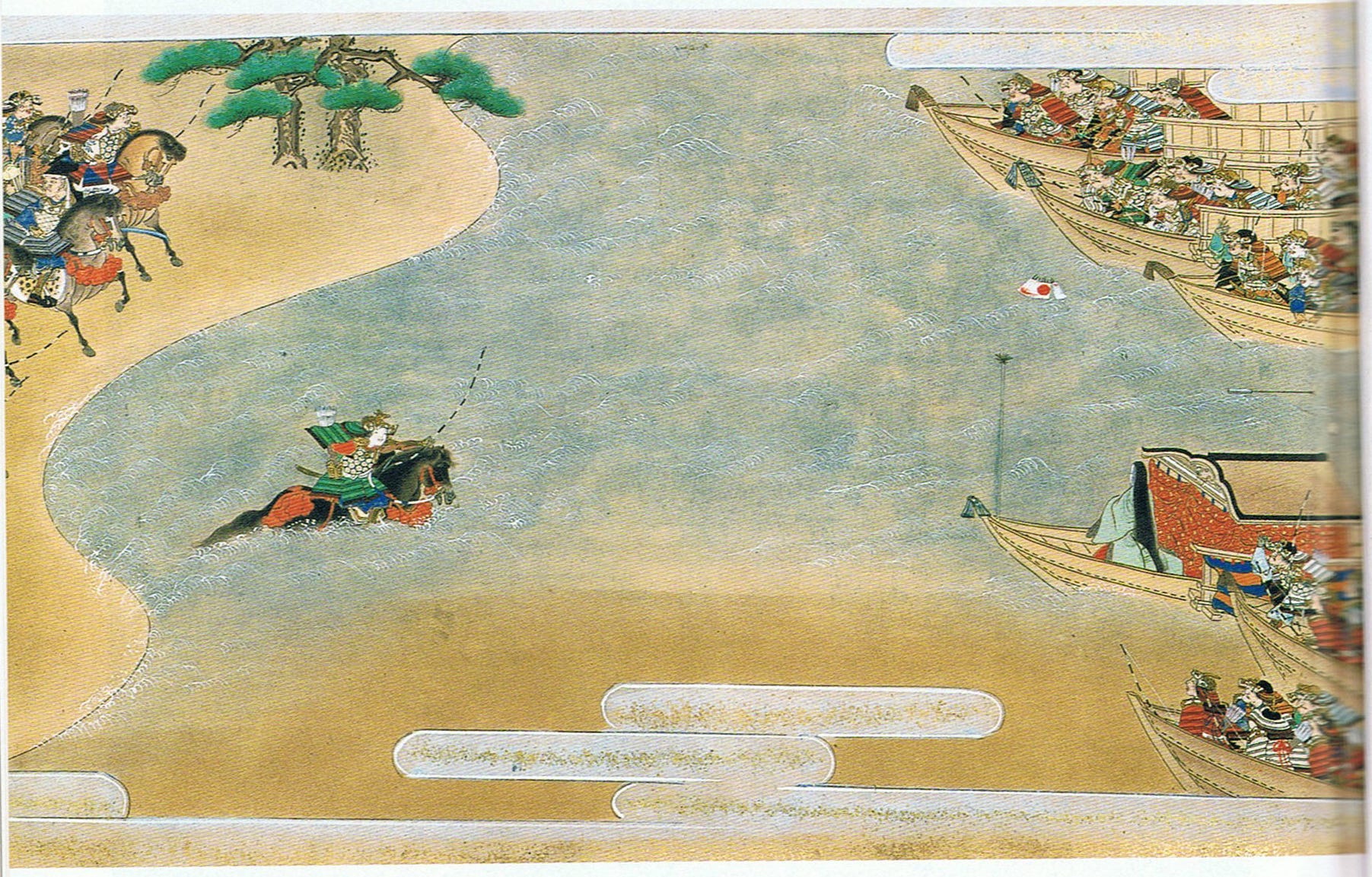

I can’t wait to share with you the rest of my work on the Genpei War, the History on Fire series I’m currently releasing. While waiting for the second and final episode (the first is here), I’d like to share a few things with you in print. Among the sources for the Genpei War (1180-1185) is The Tale of the Heike, one of the most important works in Japanese literature. Think somewhere between a history book and The Iliad. Much like Homeric epic poetry, The Tale of the Heike was recited by lute-playing bards, true masters of performance who could stir the emotions of listeners thanks to their skills in music and storytelling. Of course, much like in the case of the works by ancient historians like Herodotus or Thucydides, figuring out how much it’s factual history and how much literary embellishments is an impossible task. I fell in love with The Tale of the Heike from the very first passage. Before sharing it with you, I should mention that Gion Shoja was a place where supposedly Buddha taught his disciples, and the sala flowers are flowers of a tree under which, according to legend, Buddha was born and died. With this warning in mind, here’s the opening of the book. The sound of the Gion Shoja bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the color of the sala flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline. The proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night; the mighty fall at last, they are as dust before the wind. This is how The Tale of the Heike begins. With an opening paragraph like this, you can bet I’m reading on. Besides being colored with the kind of poetic Buddhist sensibility just quoted, the rest of the book is also packed with stories about some of the most renowned characters in the history and literature of Japan. And the tales about the secondary characters are just as powerful. Today, I’ll offer you a quick synopsis of two of these stories that will show up in part 2. The first comes from the most famous instance of single combat that took place at the battle of Ichi-No-Tani (1184). The battle itself was a big turning point in the war between the Minamoto and the Taira clans. As the Taira were fleeing to their boats, one particular clash took place between Kumagai Naozane and Taira Atsumori—a clash that would catch the imagination of writers and playwrights, and be re-enacted in theater performances ever since, becoming one of the most famous fights in Japanese history. While in Japan, I visited museums and parks that were entirely dedicated to just this one fight. So, without further ado, let me tell you why it became such a big deal. While chasing down the fleeing Taira warriors, Kumagai spotted one of them who had ridden his horse in the water and was making his way toward a boat. Seeing that this warrior was of high rank, Kumagai yelled at him, essentially accusing him of being a wimp for running away, telling him it was dishonorable to show your back to an enemy, and that the only way to redeem himself was to return to the beach to fight. You’d figure that anyone would be smart enough not to fall for this obvious bait, but the fleeing Taira was stung in his pride, so he turned his horse around and returned. Bad idea. Kumagai was much stronger. He threw the Taira off his horse, and removed his helmet to kill him. This is where things get interesting. Upon removing the helmet, Kumagai realized his antagonist was a very young lad of only about 15 or 16 years old. Worse yet, Atsumori didn’t look like some hardened warrior, but rather seemed soft and sweet. He actually reminded Kumagai of his own son who was about the same age. At this point, all desire to kill the enemy left Kumagai. However, Kumagai noticed other Minamoto warriors were rushing over: if he didn’t kill Atsumori, they would. Rather than letting them hacking Atsumori, Kumagai told his antagonist it’d be best for him to give him a clean death, taking his head with one stroke and praying for the young man’s soul. So, with tears in his eyes, he went through with his plan. After killing him, Kumagai felt already horrible enough, but the pathos of the scene didn’t end here. In looking through the young man’s belongings, Kumagai found a flute, a rather odd thing to carry into battle. He also remembered that before battle, he had heard coming from the Taira lines the sound of someone beautifully playing the flute. So, it became obvious to him he had taken the head of a wonderful musician, whose art he admired. The Tale of the Heike informs us that, distraught over what he had done, Kumagai ended up renouncing his warrior ways and became a Buddhist monk. Part of the reason why this story is so famous is because it underscores the tension between a warrior’s duty and humanity, fighting ferocity and artistic beauty, toughness and religious piety. A true tragic tale, if there ever is one. The second story comes from the battle of Yashima (1185). In one of the most famous moments of the battle, a beautiful lady from the Taira side placed a fan on top of a pole on one of their ships and challenged the Minamoto archers on the beach to hit the target. Between the waves rocking the boat, the small target and the distance, it was a nearly impossible shot. The Taira were either trying to get the Minamoto to waste a bunch of arrows or were setting them up for an embarrassing failure. Not one to back up from a challenge, the Minamoto leader Yoshitsune called one of his best archers, a samurai named Nasu No Yoichi and ordered him to take care of business. Yoichi took the responsibility a tad seriously. He vowed to either be successful or kill himself—which seems a little excessive if you ask me, but I’m not a samurai from the late 1100s so what do I know... A famous Taoist parable by Chuang Tzu recites: When an archer is shooting for fun In these lines, Chuang Tzu speaks about how emotional pressure lowers skill by robbing us of that mix of focus and relaxation that is essential to perform at optimum levels. Yoichi apparently had never heard of this parable and his mastery over his emotions was insane. With his life on the line, after offering a Buddhist prayer, he managed to hit the fan on his first attempt. Interestingly enough, the shot was so good that even the Taira cheered in admiration of the man’s skill. I’d say that when you get the people you are trying to kill to cheer for you in a battle, that’s a pretty amazing feat. I can’t wait to share with you many other great stories in part 2 of the Genpei War series (which should be out by the end of August). In the meantime, I hope you enjoyed these ones. You're currently a free subscriber to Daniele’s Substack. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |