Charlie Boy Criscola [CC BY-ND 2.0] via Flickr

Apologies for Friday’s outage, due to unavoidable delays in the delivery of adequately combustible fire-breathing fuels. Bitumen and fusel oil stocks being very nearly replenished, we anticipate no further interruptions in service. Today: David Roth, an editor and co-owner at Defector; and we are delighted to welcome new Hydra Parker Molloy, author of The Present Age, a newsletter about the intersection of media, politics, and culture.

Issue No. 142We Used to Wait

David Roth My Summer At Brain Camp

Parker Molloy

We Used to WaitThis story is part of The Lost Internet, a month-long series in which the members of Flaming Hydra revisit internet marvels of the past.

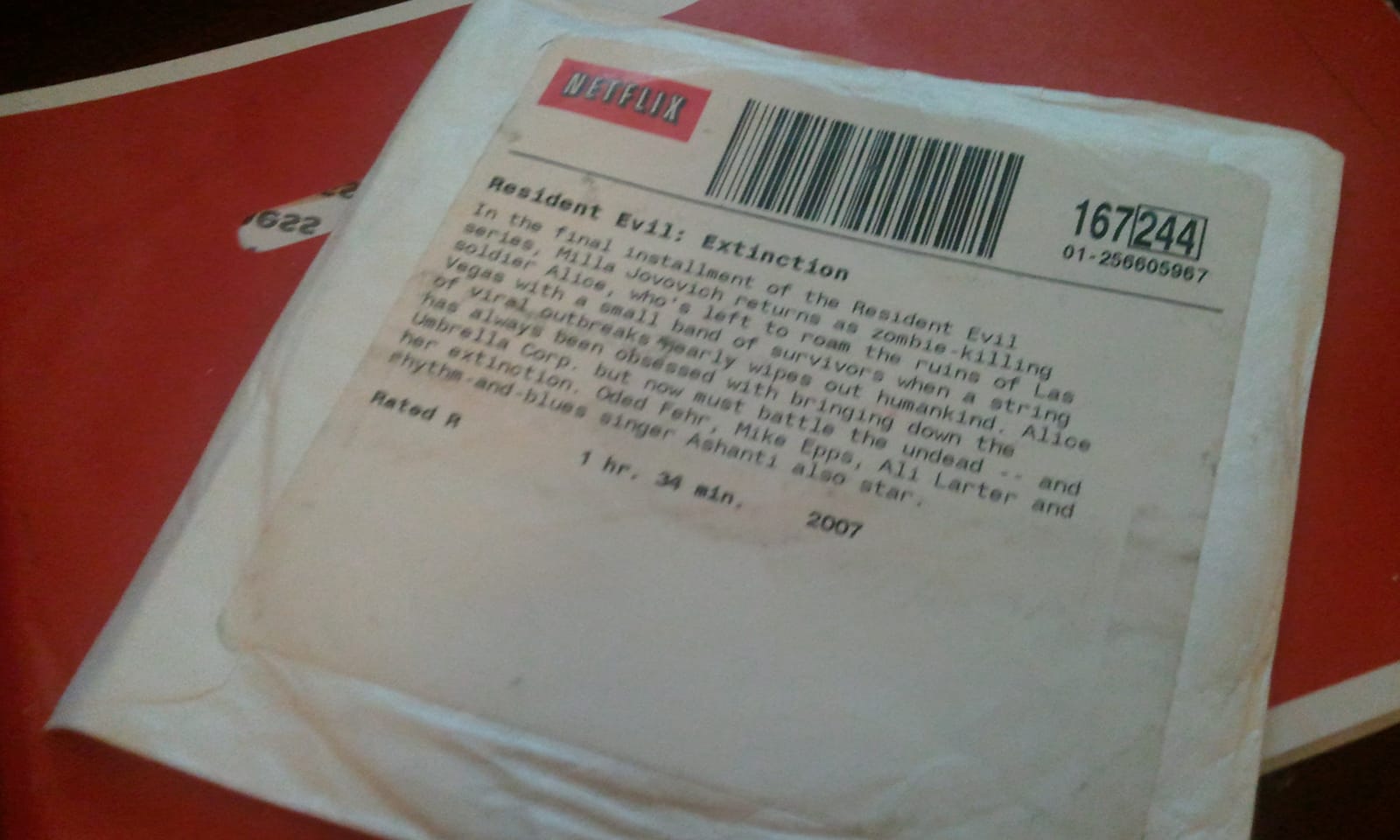

I think of Netflix mostly as a dire sort of weather system. This is unfair, maybe, as it is also and foremost an application, a very successful business, and it remains the premier place to experience the color red on film at its most dispiritingly oversaturated. Only on Netflix can you see the 2018 film Bird Box, which the company claimed was a massive global hit, or 2021’s Red Notice, which Netflix says has been viewed more than 230 million times. There are reasons to believe some or all of this, and roughly equally compelling reasons to believe none of it, but there’s no reason why anyone should care about any of it. That these movies seem like posters for fake movies that you might have seen hanging in the background of a scene from another, real movie is a much more accurate reflection of how they were conceived, and what they are for. Netflix exists, like other contemporary businesses exist, primarily to grow shareholder value; these movies are, more than anything, the proof of that growth—some numbers that turn into some other numbers—sometimes with the ancillary and unfortunate involvement of Ryan Reynolds and sometimes not. The long shadow that Netflix casts in my mind, though, suggests something more intimately sinister. As a streaming service that I mostly don’t watch, Netflix is just one button among others, the one with multiple seasons of Is It Cake? on it, but as an emblem of the cynical and anhedonic cultural moment it has come to rule, it is more than that. It is that weather system, a bleary jag of close, dense, stifled bright-gray days when it doesn’t even really seem to cool down at night. It always looks like rain but the air just swells and swells instead; it is stifling in ways that somehow turn people into much worse drivers than they ordinarily are; it is a heat that wakes up the bad smells latent in the pavement, somehow, such that the layered ghosts of ancient piss haunt even the shortest walks. You can’t do anything with it, because weather isn’t negotiable like that and because the decisions that brought it down over everyone were made some time ago. The traffic just sits there, fuming haplessly in its stink. There are legible technical reasons why all Netflix productions tend to Look Like That, but the reason it feels the way it does is that it sucks. It’s this that is replacing television and not so much eating as idly chewing on the movie business. Everything looks wrong, it’s too bright or too clear or else soggy with grayed-out CGI murkiness; it feels like you’re watching it on your phone even when you’re not. It feels like you’re watching it on your phone on a slow-moving bus, really. A host of recognizable artists is there on either side of the cameras but their talents seem somehow diminished, in many cases they look and feel a bit more haggard and sad; it is not the images that seem overcompressed but the stories and performers in them. Some of that is maybe the result of all these stories unfolding in a world in which the color red is all fucked up, which would bum me out as well. But a lot of it is very plainly earned, a pinched smallness that radiates from the inside out. It feels bad. And yet, somehow, when the question was posed to the Flaming Hydra team of what we missed about the vanished or vanishing internet, my first thought was of my Netflix queue. This was some time ago; we both wanted different things, then, Netflix and I. What I mostly wanted, cycling through periods of what could only nominally be considered employment and shorter, more anxious periods of what I thought was freelancing, was for werewolf movies of my choosing to be delivered to my home on DVD. I needed money for rent and food; I wanted to make that money from writing instead of doing other things, and mostly had not yet figured out how to do that. Netflix, which at the time was a service that sent DVDs to your home in exchange for a monthly fee, was largely extraneous to the fundamental challenges in the previous sentence, but it also played a bigger part in my life than I feel comfortable acknowledging even now. Here, and basically only here, I planned ahead with some delight; Netflix expedited this, and built a large and growing business in doing so. A symbiosis, of sorts; I wouldn’t have said we were friends. During periods of low inspiration and employment, when I was getting my ass handed to me pretty much every day in pretty much every other facet of life—doing but mostly just occupying various temp jobs at a reliably hungover B-minus level, having my pitches and stories rejected and ignored, and learning very little from either experience—my command of my Netflix queue, the care with which I programmed the hours during which I might have been working, was a rare area of mastery. I was not much of an employee, and not yet much of a writer, either, but the DVD of Neil Marshall’s Dog Soldiers that I got in the mail was watched and back in the mail within 24 hours. I attended to my Netflix queue with a degree of close attention that I could not or anyway certainly did not bring to any other aspect of my days. I’d been this way with video stores before, but those were already going away; Netflix was not yet in the streaming business, nor yet an experiment in the algorithmic manufacture of taste. My relationship with it was appealingly binary—they sent me a movie and I received it, and then we ran it back in reverse—and existed on a scale that I could manage. (This has been the most interesting throughline to the Vanishing Internet essays, I think: the extent to which the thrill of being online seems to curdle once it leapt from computers and onto our phones, and from being a sort of escape and into something inescapable.) I rated the movies I watched and received recommendations from the site in turn, and I considered those and incorporated them into my queue in turn. Even the queue itself, a list of titles sprawling deep into the triple digits, proved instructive, as I ranked and re-ranked and so reasoned my way towards an understanding of what I actually wanted to watch as opposed to what I merely wanted to want to watch. Part of the promise of the internet, as I have experienced and understood it, always came down to its oceanic and ungovernable vastness. I do not want to conquer it, and I am aware that, in the same blank way that the ocean is, it is home to a lot of things that would be happy to eat me right up. The pollution and predation to which it has been subjected by human thoughtlessness has made the internet a hotter and more volatile and less hospitable place. There are so many jellyfish out there now, and even the high tide stinks of rot and gasoline. This is the weather system that today’s Netflix feeds and is fed by; a service that once sent me what I wanted grew and grew, optimizing and refining itself ever farther from those simple and useful origins into something that can only offer me things I don’t want—overwhelmingly, artless, spammy, and uncanny things that Netflix itself makes or buys in the belief that it has unlocked some algorithmic secret solution to the question of “what people want to watch,” when the point of it and the fun of it, and the bit I miss most, was the work of figuring all that out for myself. Of course the reds are wrong, and the grays bleed artifice from the edges of every frame, and the stars are shrunken and dim. Netflix is compressed in every way, no longer invited or received into the time allowed for it but quite literally and neverendingly piped in. The care that once held it all together and gave it real dorky verve—which came from the people programming their idle hours from the shelves of a video store without walls—has been replaced with something colder and more predictable, something that feels and functions much less like a decision than it used to. The old way just didn’t scale.

A FIERY ROAR OF APPROVAL Flaming Hydra Kim Kelly: BRAVISSIMA!! Congratulations to Kim Kelly on winning the American Society of Journalists and Authors Articles That Make a Difference award for “The Young Miners Dying of An Old Man’s Disease” in In These Times!!

My Summer At Brain Campby Parker Molloy 'Spring', Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1563); public domain via Wikimedia Commons Late in the spring, I stood at the entrance of an unremarkable office building, my hand trembling slightly on the door handle. The air around me was thick with the promise of summer warmth and sweetness, but I could feel only numbness and dislocation. I felt transported back in time. Suddenly, I was five years old again, clutching my lunchbox on the first day of kindergarten, a rush of fear and uncertainty threatening to overwhelm me. Weeks earlier, I had sat across from a psychologist as she gently explained the results of my neuropsychological evaluation. My years-long struggles with severe depression and anxiety had hit a boiling point. I needed intensive help. Once through this glass door, I would step into a partial hospitalization program (PHP). The woman staring back at me in the door’s reflection was a stranger—lost, broken, hollow-eyed, held together by little more than sheer will and desperation. As terrifying as it was, I dared to hope that maybe this could be the beginning of something transformative. A lifeline. I took a deep breath and stepped into the unknown. Despite its severe-sounding name, a PHP doesn’t actually take place in a traditional medical setting. Instead, it consisted of group therapy sessions in a classroom-like environment. There I would learn an alphabet soup of therapy approaches that would serve as the foundation for my treatment: dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and cognitive processing therapy (CPT) skills. I had regular one-on-one sessions with both an individual therapist and a psychiatrist. After the first three weeks in the PHP, I transitioned to an intensive outpatient program—that meant fewer hours spent in therapy each week, though the work remained the same. Each day brought new insights, some more welcome than others. The DBT skills became my anchor, teaching me how to navigate the stormy seas of my emotions without sinking. I learned to identify my feelings with precision, labeling each one as it arose: anger, fear, sadness, joy. It was like learning a new language—the language of my own mind. CBT sessions felt like archaeological digs into my thought patterns. We unearthed beliefs I’d held for years, examining each one under a harsh light. Some crumbled under scrutiny, while others proved more stubborn. I began to see how these thoughts had shaped my reality, often distorting it in ways I hadn’t realized. The ACT group was perhaps the most counterintuitively helpful. Instead of fighting my negative thoughts and feelings, I was encouraged to make room for them. This approach felt foreign at first, but slowly, I began to feel a sense of freedom in accepting my experiences rather than constantly battling them. Throughout it all, my fellow “campers” became an unexpected source of strength. In their stories, I saw reflections of my own struggles. We shared knowing looks during sessions, celebrated small victories together, and offered silent support when words failed. There was a camaraderie in our shared vulnerability that I hadn’t experienced before. But “brain camp” wasn’t all breakthroughs and bonding. There were days when I felt like I was moving backwards, when the skills we learned seemed impossible to apply in the real world. The voice of my depression, ever-present, would whisper that this was all futile. Yet somehow, I kept showing up, day after day, driven by a mix of desperation and a tiny, growing spark of hope. As my time at “brain camp” came to an end, I found myself at another threshold. The woman in the mirror was no longer a complete stranger, but she was far from healed. Depression and anxiety aren’t foes easily vanquished, even after months of intensive therapy. I’d love to say that I emerged from the program completely transformed, my mental health struggles a thing of the past. The reality is far more complex and, frankly, more difficult. My depression still weighs heavily on me, clouding my days with a familiar darkness. Anxiety continues to twist my thoughts, filling me with dread and uncertainty. But amidst these ongoing battles, I now possess a toolkit I didn’t have before. The skills I learned—DBT, CBT, ACT—haven’t cured me, but they’ve given me a fighting chance. On my darkest days, when getting out of bed feels like climbing a mountain, I can reach for a DBT technique to help me weather the storm. When anxiety screams that everything is falling apart, I can use my CBT skills to challenge those thoughts, even if I can’t silence them completely. As I transitioned back into the world outside of “brain camp,” trepidation and hope welled up in me again. The protected space of intensive therapy had become a cocoon of sorts, and emerging from it was both liberating and daunting. Some of my fellow campers and I made plans to stay in touch; we created a group chat where we could share our ongoing struggles and victories. These connections became a safety net, allowing us to compare notes on applying our new skills out in the real world. It was comforting to know that others were navigating similar challenges, trying to integrate their therapy experiences into daily life. The stark contrast between the structured environment of the program and the chaotic unpredictability of everyday existence has been jarring at times, but having this support network has eased the transition. As we each found our footing, our group became a reminder of the progress we’d made and the shared journey we continued to undertake. My new tools don’t always work perfectly. Sometimes, they feel impossibly hard to use. But their mere existence gives me a sense of agency I didn’t have before. They remind me that even in my struggles, I’m not entirely powerless.

Thank you for reading our blogs. Please subscribe, and tell your friends to subscribe, so that we can keep breathing FIRE with you.

|