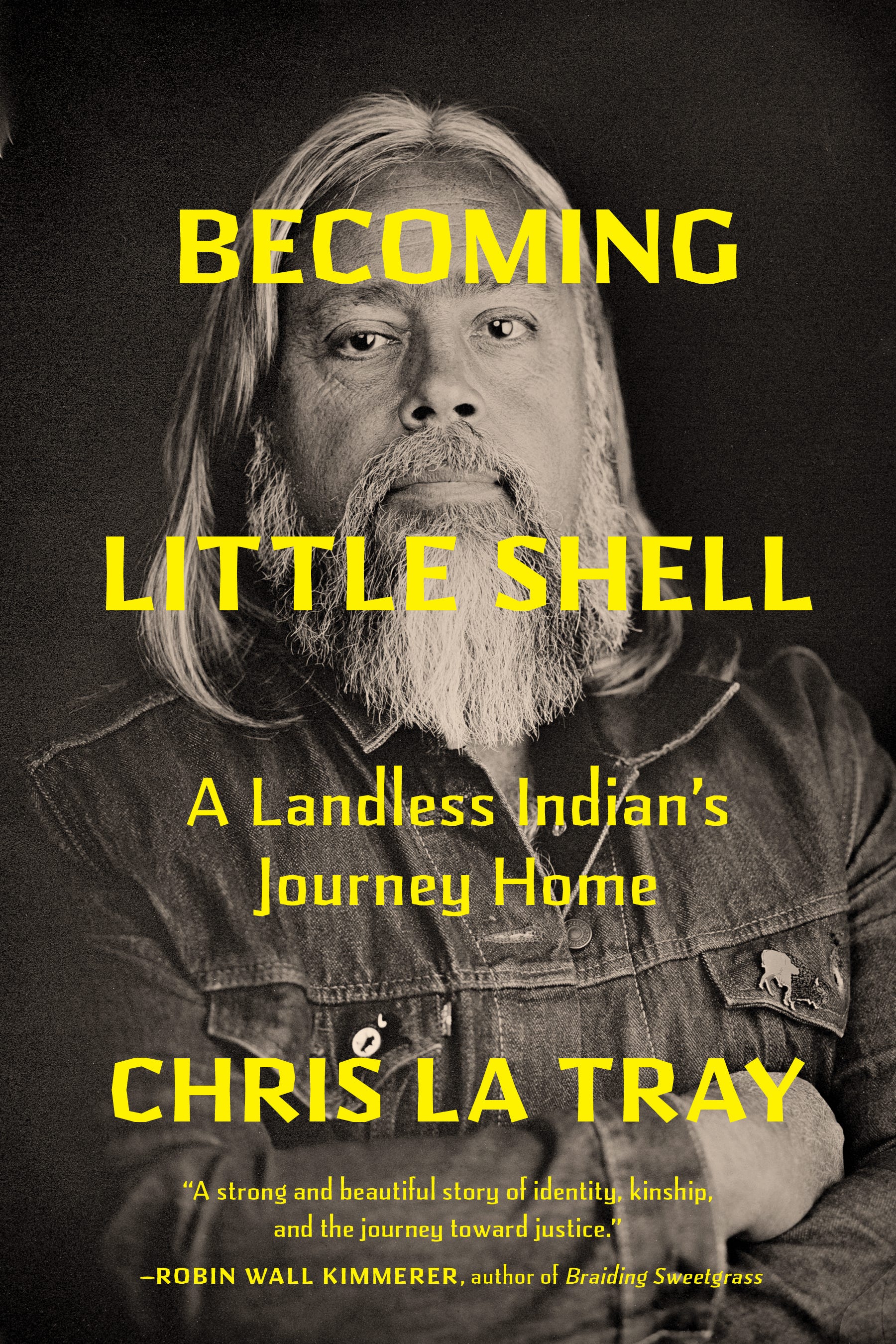

Subscribing makes this work sustainable — and makes it possible to offer almost everything I write for free. (Which makes it easier for you to send it to people and discuss!) Your subscriptions keep the paywall off articles like this one. Subscribing gets you access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive monthly links/recs posts, full Garden Study access, and all the weekly threads and discussion — like Tuesday’s typically massive What Are You Reading, August Edition, where, in addition to filling your TBR pile, you can read a whole bunch of divergent thoughts about Miranda July’s All Fours. If you’re exasperated by social media, this still feels like a really good place to be on the internet. I hope you’ll join us. And don’t miss this week’s episode of The Culture Study Podcast — an incredibly well-timed episode about ambition and Ben Affleck. If you’ve read this newsletter over the last few years, you know I’m a card-carrying member of the Chris La Tray fan club. His newsletter, An Irritable Métis, is one of a very small handful of newsletters I open immediately whenever they land in my inbox. His writing both challenges me and makes me feel at home in the world; he is deeply funny and readily moved and his broad love for the world, and anger at all the ways we’ve fucked it up, is always right there on the surface. His writing is deeply, persuasively human — and also deeply Montanan, in ways that challenge and rewrite the narrative of what “Western” writing (or “nature” writing) should look like. I’ve been eagerly awaiting Chris’s new book, Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home, for nearly five years. The book interweaves the history of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians and their decades-long quest for federal recognition and Chris’s own journey to understanding his family’s past, his own identity, and becoming an enrolled member of the Little Shell Tribe. It’s a story about the American erasure of Métis identity, about family stories and denial, about the colonial math of blood quantum, and so much else — and it’s a really, really good story. A maddening story, a complicated story, but also a glorious one, shaped by Chris’s indelible voice and sense of place. If you’re unfamiliar with Chris’s writing, I hope you read below (or check out one of my favorite interviews with him here) and take a chance on subscribing to his newsletter. And if you are familiar with his writing — which I know so many of you are! — I know you’ll love this conversation as much as I do, and hope you get your hands on Becoming Little Shell soon. I think there’s often a hunger for a cinematic revelation about identity: something very Henry Louis Gates Finding Your Roots style. But your book underlines the way identity is far more often an act of becoming: of combining information you’ve always known, of re-examining conversations you had decades ago, of haphazard connection and a lot of forms. I really appreciated the section where you describe attending a meeting where you thought you’d learn if your application for tribal membership would be approved, and it was incredibly anti-climatic. Can you talk a bit more about how you processed the relatively mundane parts of the process and how they’ve become meaningful — both to you and on the page? This sounds like kind of a copout but it’s really the mundane parts of our lives that comprise the bulk of our lives, aren’t they? So spiritually there are people who might consider themselves Christian or Buddhist or whatever, but they practice those aspects of identity only in performative moments like showing up for Midnight Mass on Christmas, or some retreat they go on once a year, or in front of an audience of googly-eyed sycophants … but then act like assholes the rest of the time. So for me to claim any kind of identity as an Indian I realize I need to live it every moment of every day, or as best I can. Not just at powwows or when it’s convenient. So that’s what I’ve tried to incorporate into my life, this daily grind of what it means to be an Indigenous person. It isn’t easy, but name anything any of us try and embody that isn’t! Because that’s what it is, it’s an embodiment. There is this idea I return to all the time, talk about all the time, that comes from a quote by one of our late elders, Eddie Benton Banai. He said that to live an Anishinaabe life, to live according to our Seven Grandfather teachings, is to live a life where every footstep becomes a prayer. Isn’t that beautiful? You know how when you walk through a field in late summer and grasshoppers are clicking and whirring all around you in your wake, just erupting off in every direction? That’s what I imagine “every footstep a prayer” to be, only those grasshoppers are the prayers Eddie mentions, exploding from the loving impact of our feet with the earth. Traditionally, most Indigenous cultures were constantly in prayer with and making conversation with the spirits around us. What a beautiful way to live. That’s what I try and do: make life a constant ceremony. It deserves it! What part of the process gave you the most trouble, for lack of a better word? (You can think of this in terms of subject matter or reflection or style or editing or WHATEVER) I’d especially love to hear about how some of those troubles may or may not have intersected with your desire to approach this book as a storyteller, not a historian. How do you tell the story of your own history? I was more interested in approaching it more as a historian, journalistically, whatever, because I love books like that. I feel like we’ve been in a golden age for a decade or more of narrative nonfiction where history has been shared with us by magnificent storytellers. That’s what I wanted to do! I wanted to write one of those books! And the only way I could get my head around the story was to approach each chapter as I might a magazine article and write it that way in chunks that I would hopefully tie neatly together in the end. As journalists (I’m not one, I just crash the pool sometimes like the caddies in Caddyshack) kind of the first rule is to keep ourselves out of the story. And I did! The first draft was definitely more me as a distant narrator sharing all of these facts and dates. Of course when I turned it in the first thing my editor – Daniel Slager at Milkweed – said was that the book needed more of “me” in it. Which was no surprise, really. Throwing a tantrum and ignoring it for a few weeks before going back and reworking it and deciding what parts had to go and what parts really needed to stay was the hard part. Let alone stomping around in my own memory and reliving some things that I’d forgotten about. I’m a private person and deciding how much to reveal was difficult. Some stuff I just don’t like to discuss, even things that are typical grist for small talk for people who aren’t surly and suspicious all the time. I see my dad in me when it comes to that. It wouldn’t be unusual for someone to ask my dad, “How’s it going?” and the answer could be, “What’s it to ya?” I’m a constant swirling muck of inherited kneejerk overreactions that I try and keep controlled all day every day, which isn’t a complaint because I inherited a lot of great stuff too. You talk a lot about questions you can never know answers to, because those answers are with your father and your paternal grandparents, all of whom are now gone. Acknowledging that your dad may or may not have answered any of these questions, I’d still love to know what you most wish you could ask each of them. I would just really like to know how much of where we come from my dad knew. He had to have known some of it. Because I’m telling you, I am so fucking proud to be who I am as a descendent of people who were so mighty, who overcame so much. My mom tells me of my great grandmother talking to her sister in their Native language; did my grandma know it too? Did my dad ever hear it? I just wish I could know. I know nothing of my dad’s life and that really bums me out. I also wonder what my dad might think of this book. It’s a fucking love letter to who we are and where we come from. I hope he’d appreciate it but I don’t know that he would. It’s probably the hardest thing about this book being out, the not knowing, the never gonna knowing, the stirring-up of all that, over and over. Maybe the answer will come through the connection of the book to other people who feel the same way my dad did, because there are a lot of them. Who knows. Sometimes book authors have a lot of say in their covers; sometimes it’s more like “pick between these three options, and we’ll take your notes under consideration.” You’ve talked openly about your ambivalence with having this image of you on the cover, and I feel like it’s a good way of talking through some broader issues you’ve been grappling with when it comes to your story/the story of the Little Shell. Why were you reticent to use the image, and has your thinking changed at all over the course of the promotion of the book? There wasn’t much discussion about it, really. I’d sent that photo in as part of a questionnaire thing Milkweed gave me that included the need for an author photo. It was maybe five minutes later (it seems like, heh) they came back and said they wanted to use my author photo for the cover and made a compelling case why. I was pretty ambivalent initially but as time passed I got more and more uncomfortable. Isn’t it only assholes like Elon Musk who put their faces on the covers of their books? I’m also uncomfortable about the perception of drawing extra attention to myself and having my face out there, every-fucking-where these days, stokes that furnace. IT’S GOING ON A BILLBOARD IN GREAT FALLS, FFS! At the same time, when I step back from the horror of my face staring at me from all those books I do see the faces of my ancestors. There were many faces just like mine comprising brigades of the mightiest buffalo hunters ever and I can get down with that, people who opposed the Americans and the Canadians and even other Natives as necessary and never backed down. The Cree called us the people who own themselves, and that is another aspect of being Indigenous, of being Métis specifically, that I seek to embody. But yeah, the face-on-the-cover is a little rough. I get constant and regular ribbing about it from my friends at Fact & Fiction, who I love and keep me sane. My friend Mara, who owns the joint, told me after a long week of fulfilling preorders, “I shoved yer head into a bag and then into a box/priority envelope over 600 times this week.” That’s just one example, heh. At the same time, if the picture inspires someone like Reese or Oprah or Jenna or whoever to bite the tip of their finger and murmur, “Ooo, I’d like to get that guy on my show….” along the way to selling a few tens of thousands of copies of it, then the sacrifice will have been well made. I’m willing to suffer that for my people. I found the end of the book profoundly moving for so many reasons. One of them was this passage: “The Indigenous part of who I am is still blossoming, and I do my best to embody it every day. All too often, now I’m someone people come to with questions about where they come from. They’re farther back down the path of discovery than I am, but the trail is still all too familiar to me because I’m on it too. So I take my answers, my ability to answer, seriously.” What’s difficult about this work? What’s essential? Nicholas Vrooman was a guy whose work as a historian and folklorist and just a full-on cheerleader for our people was essential to our federal restoration. He carried our torch, said yes whenever he was asked to go and talk about the landless Indians, the Métis, the Little Shell. When he died, someone had to carry that torch forward and it’s me, though I don’t know that I ever made the choice. If not me, who, right? A young relative asked me at an event one time if I feel chosen for this and I was answering yes before I’d even thought about it. That sounds woo-woo as fuck but I do feel chosen. I feel my life has unfolded in a way that prepared me to do this work and along the way, especially so in the last decade, so many doors have opened that shouldn’t have and I feel the weight of the hands of all of my ancestors on my back urging me through them. So the essential part of this work is to show up. Show up when asked to represent my people, show up for people who contact me with the stories of their profound loneliness in trying to return to who they should have been. It’s essential I show up for them because people showed up for me. That showing up is also the difficult part because some of those stories are hard, and they are a constant trigger for my own loneliness and the guilt that rises for things I don’t know, even as there’s no way I could know! I haven’t yet found a good balance between showing up and taking time for my own healing from the wounds that open as this road continues to unfold. But I trust the help will be there when I need it. ● You can buy a signed copy of Becoming Little Shell from Missoula’s Fact & Fiction Books — and you can subscribe to Chris’s wonderful newsletter below: If you appreciate this break in your day and the labor that goes into it, consider subscribing — I love not paywalling stuff like this, but it only works because of subscribers like you. |