Intel Missed the Party, while AMD's ZT Systems is the Bet to Stay in the GameA conversation about Intel and AMD and missing platform shifts.First, let’s start with Intel. Intel had a pretty poor earnings result. There’s no two ways about it. Intel reports Q2 EPS $0.02 ex-items vs FactSet $0.10, announces $10B cost reduction plan; suspends dividend

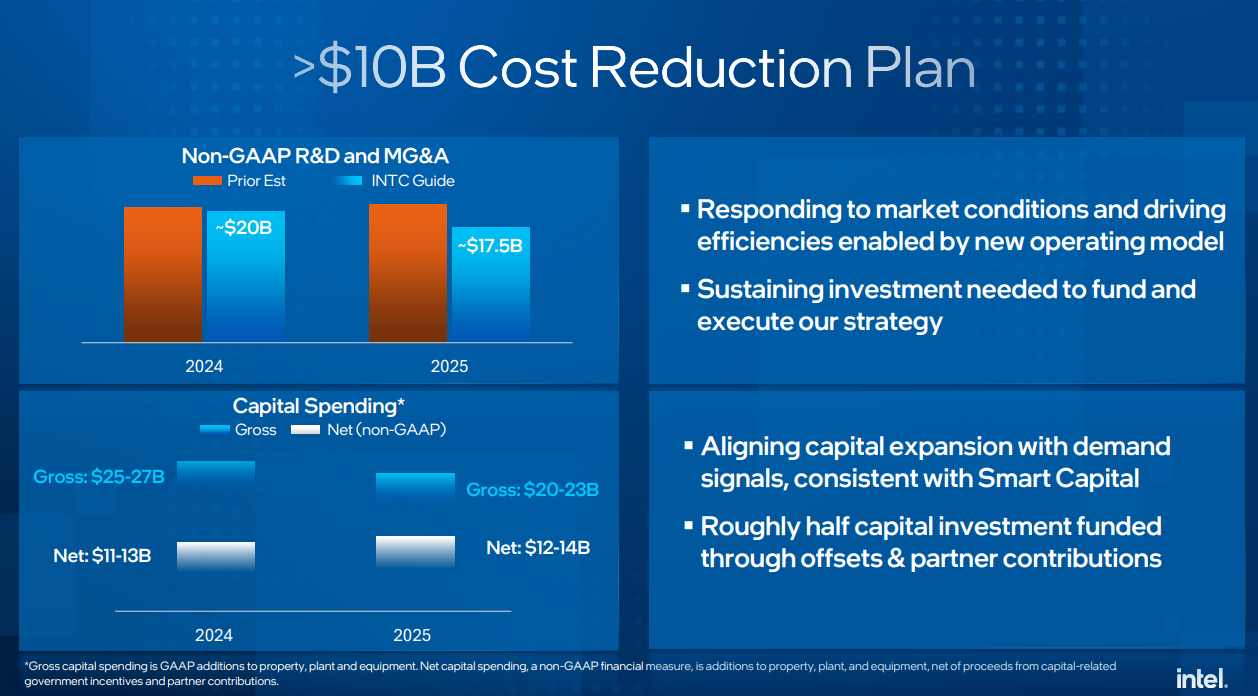

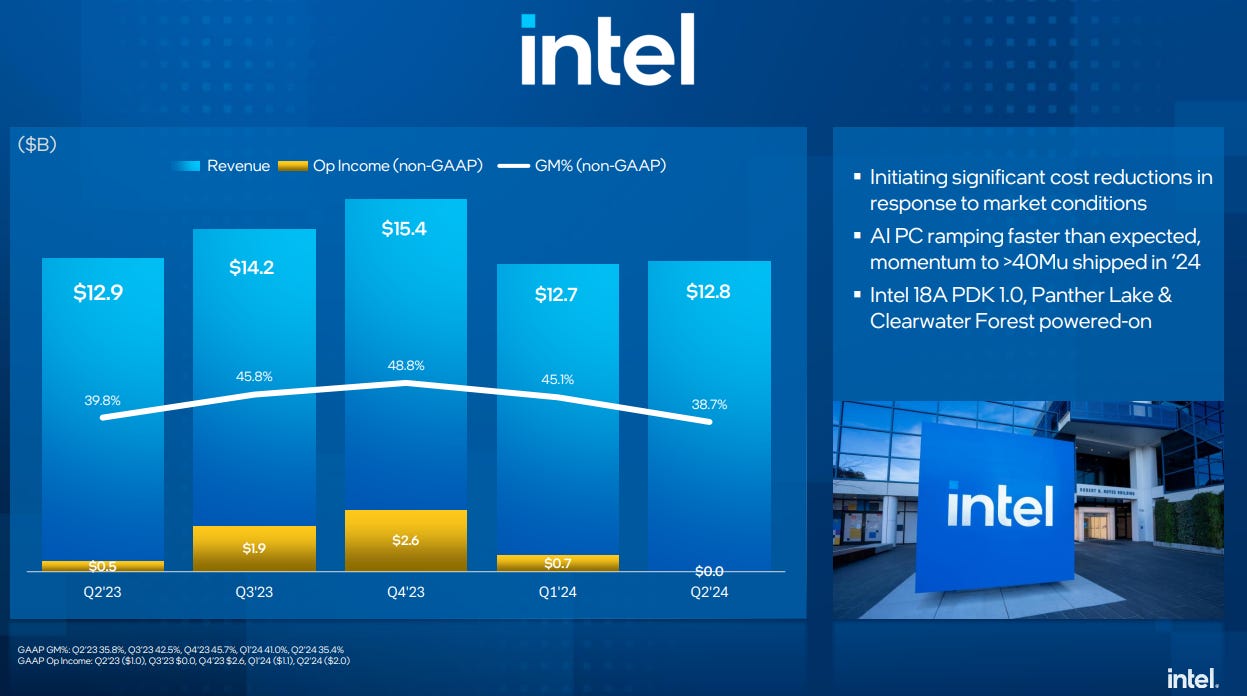

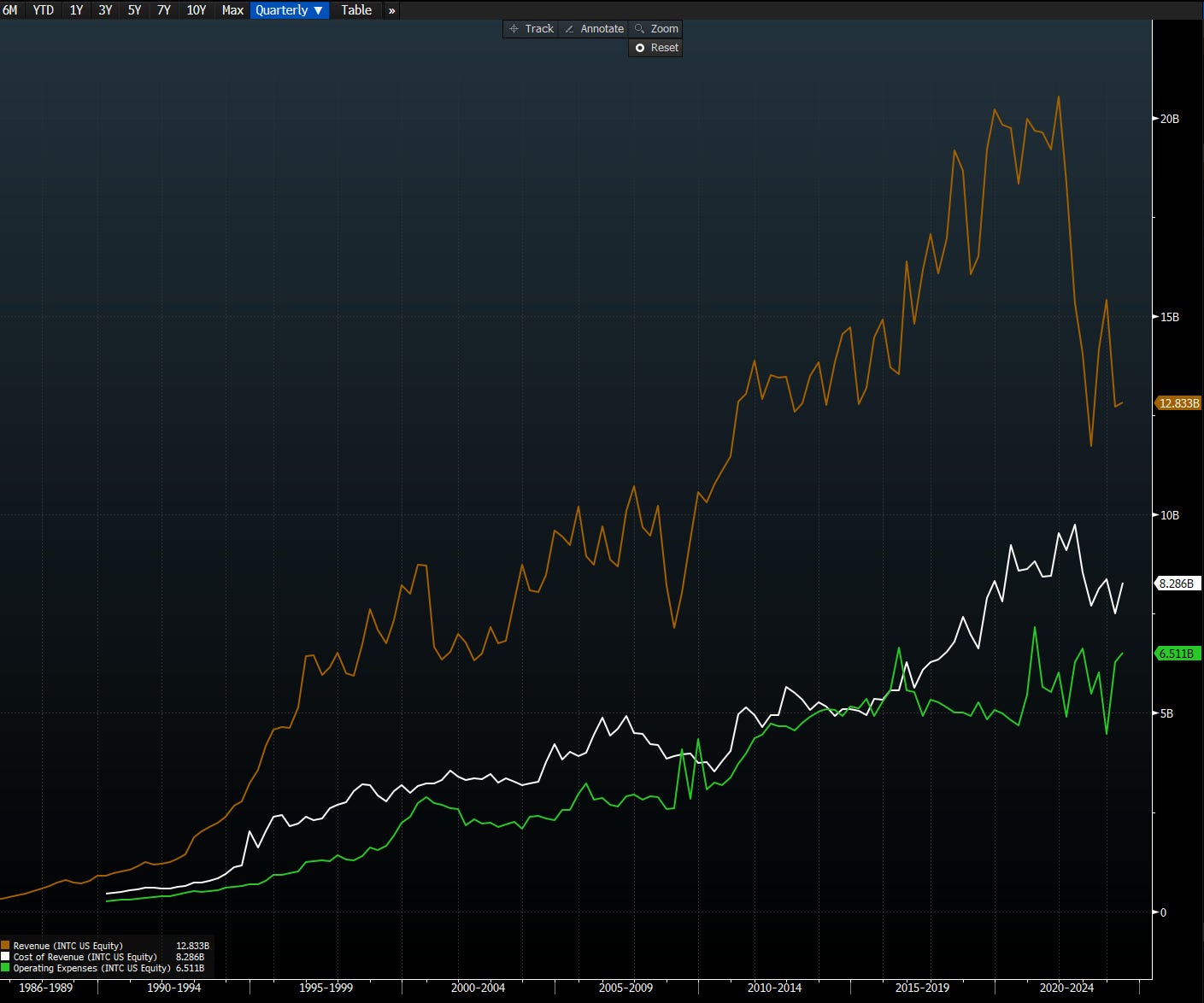

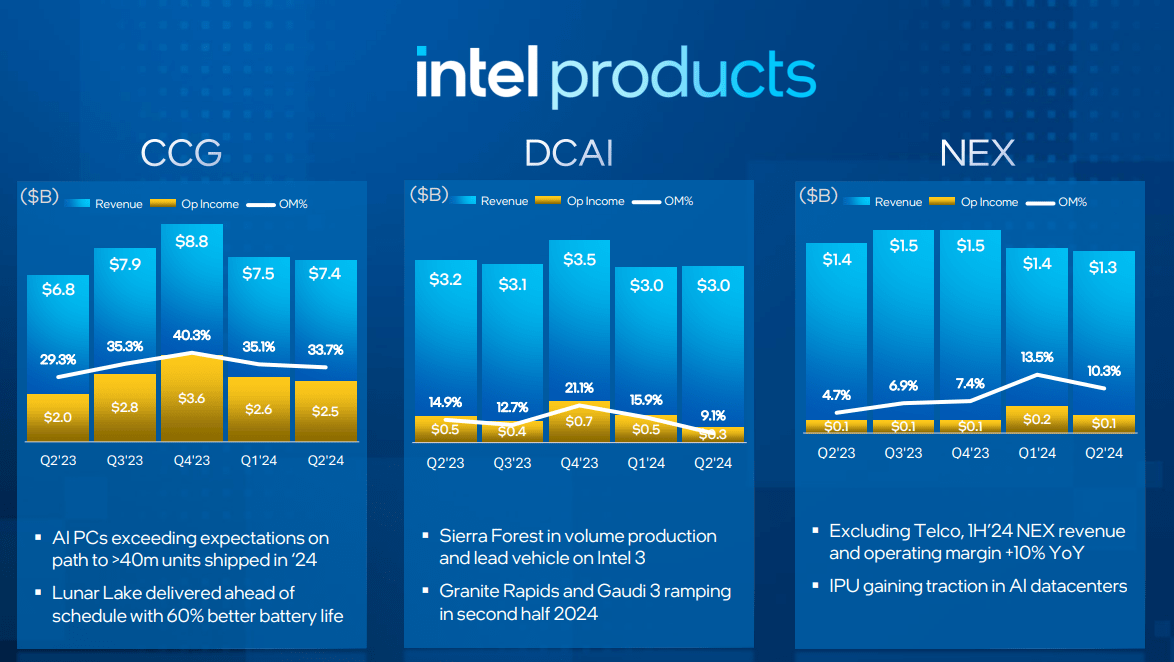

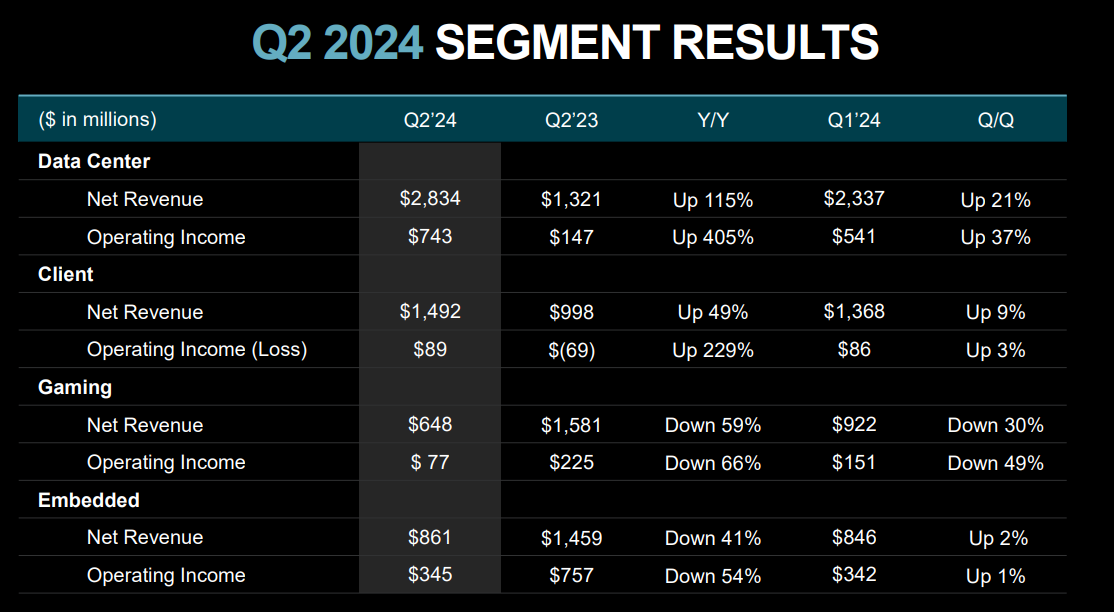

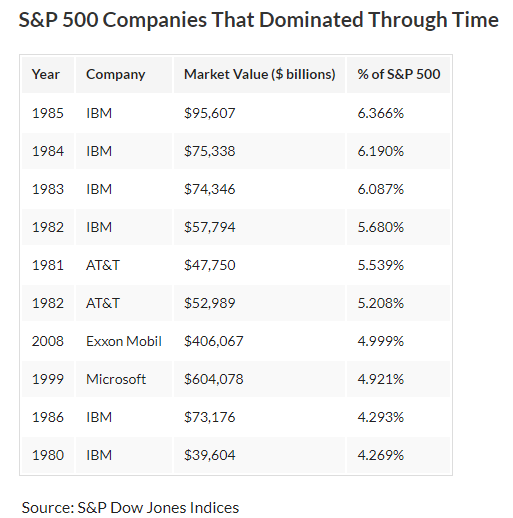

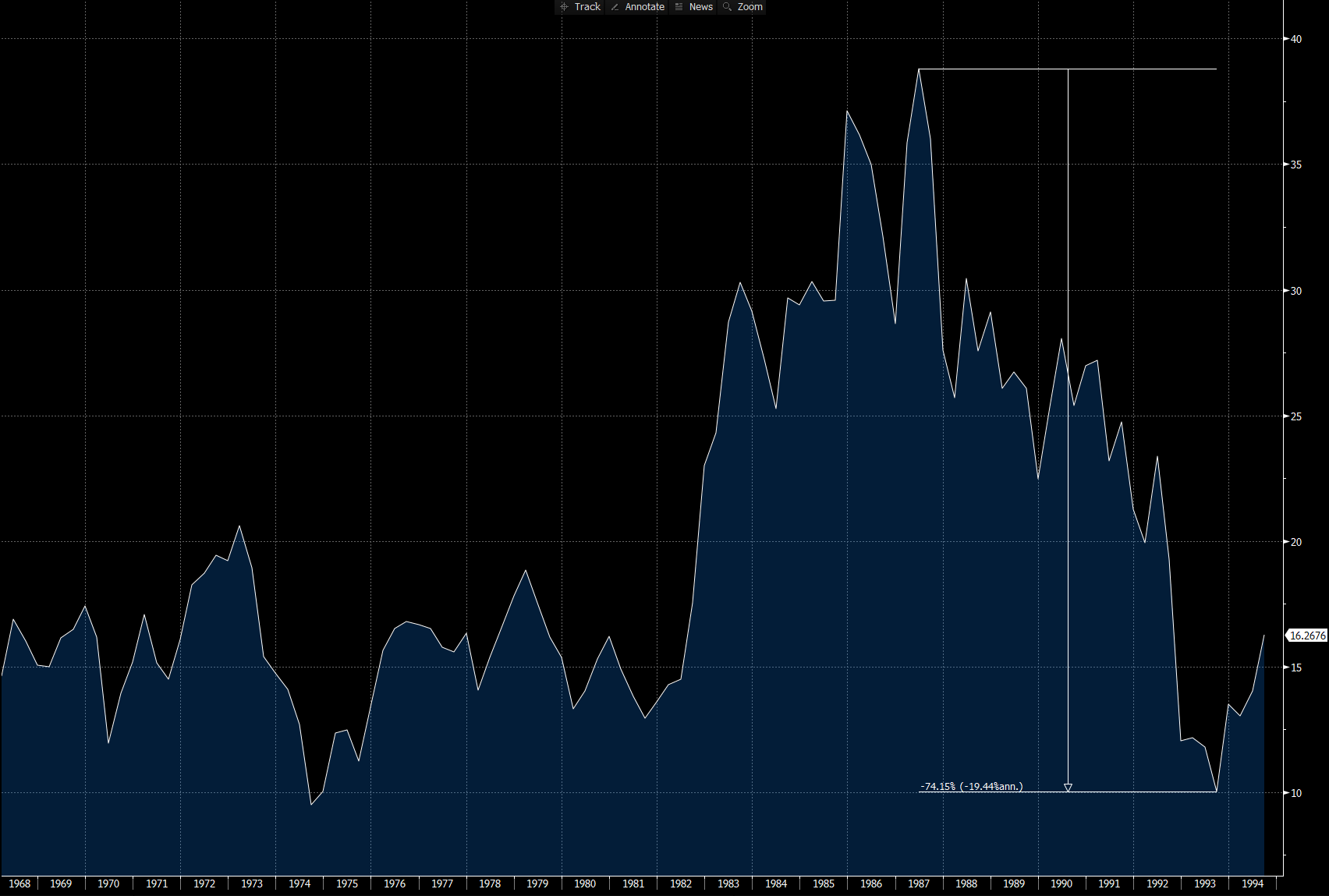

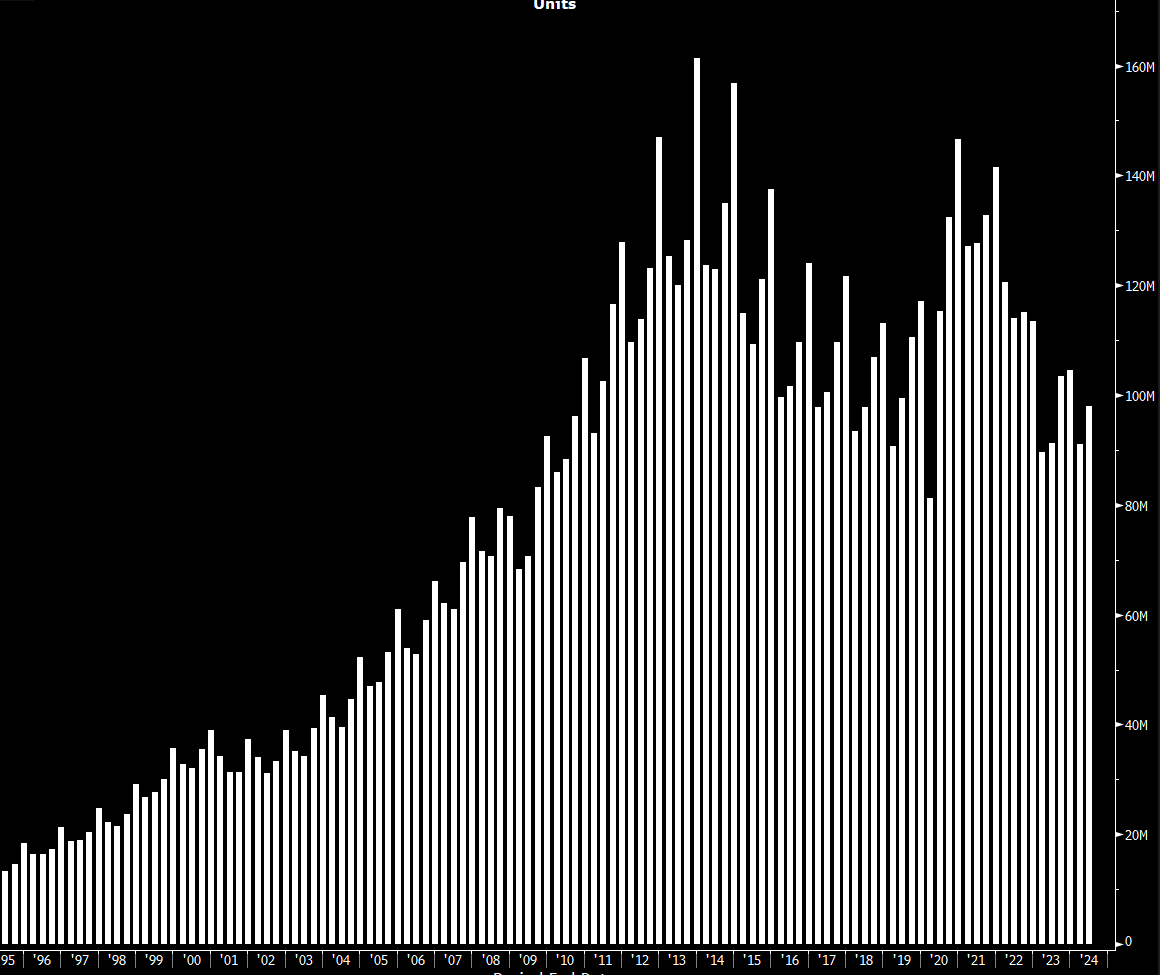

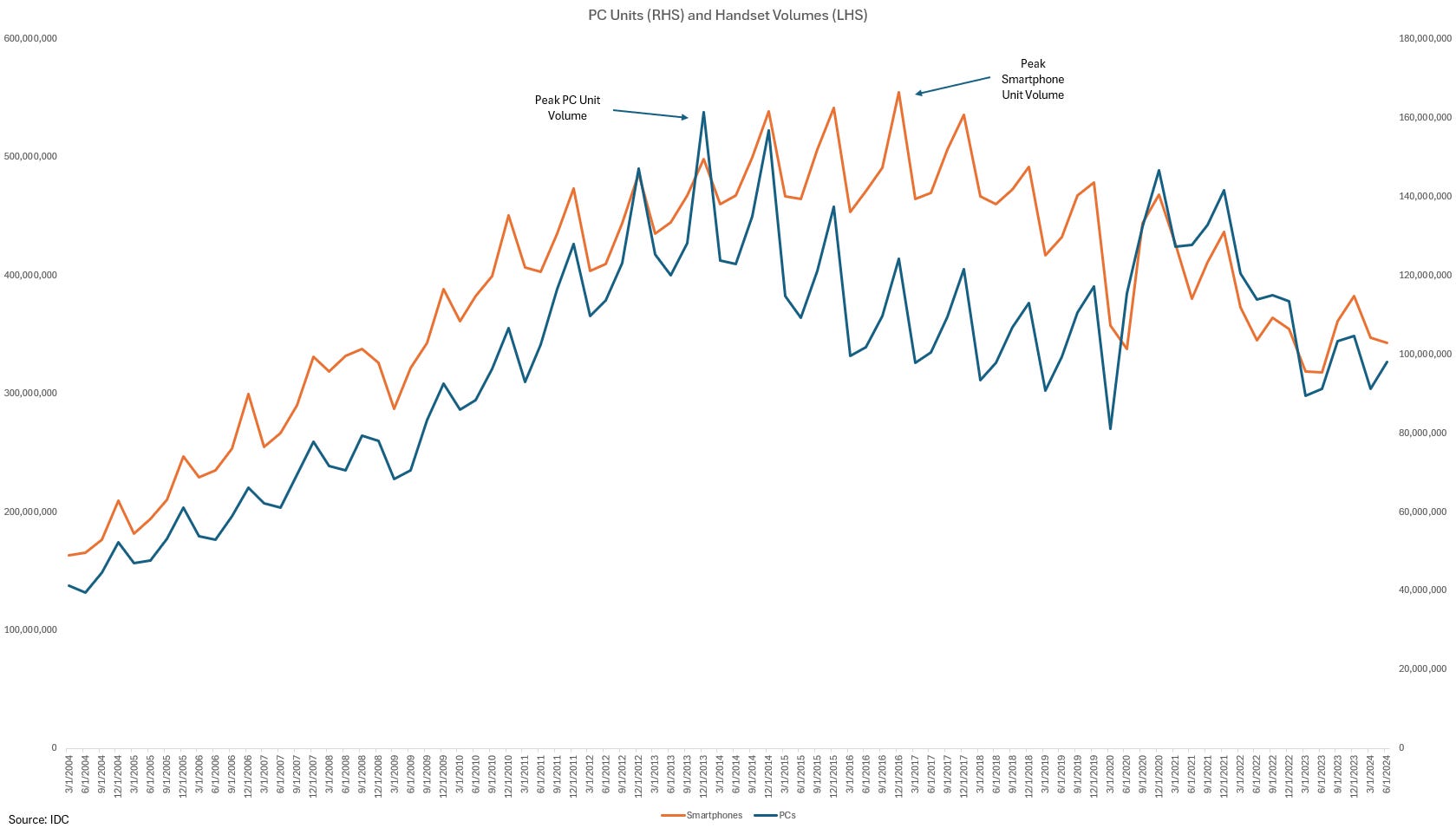

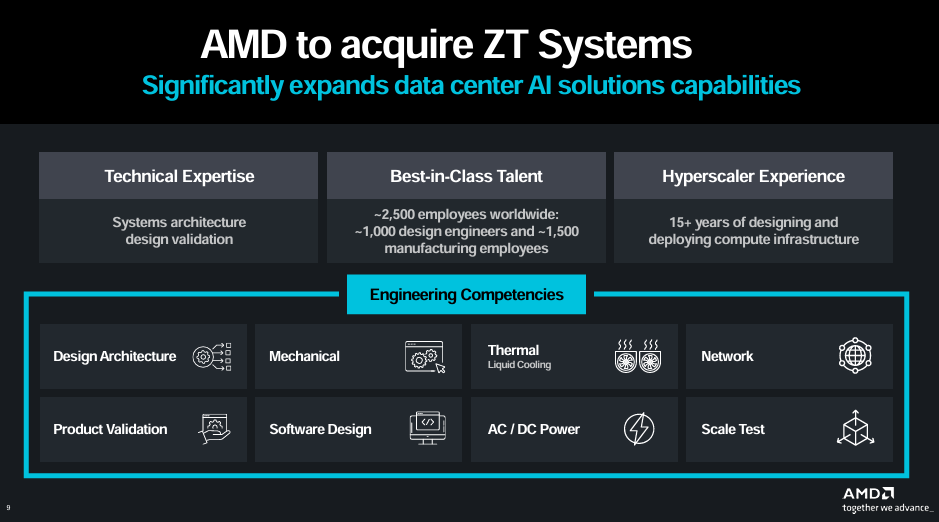

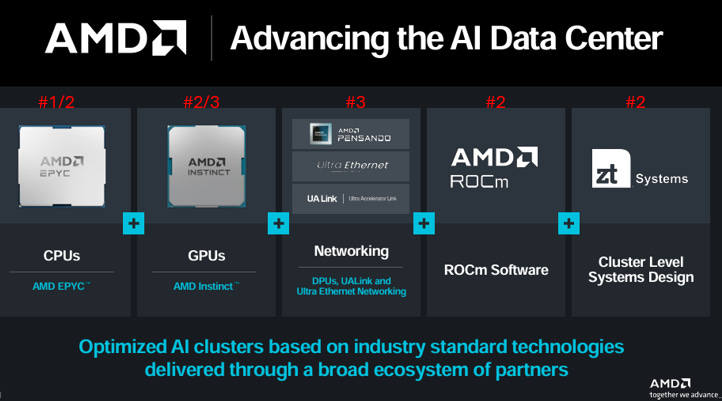

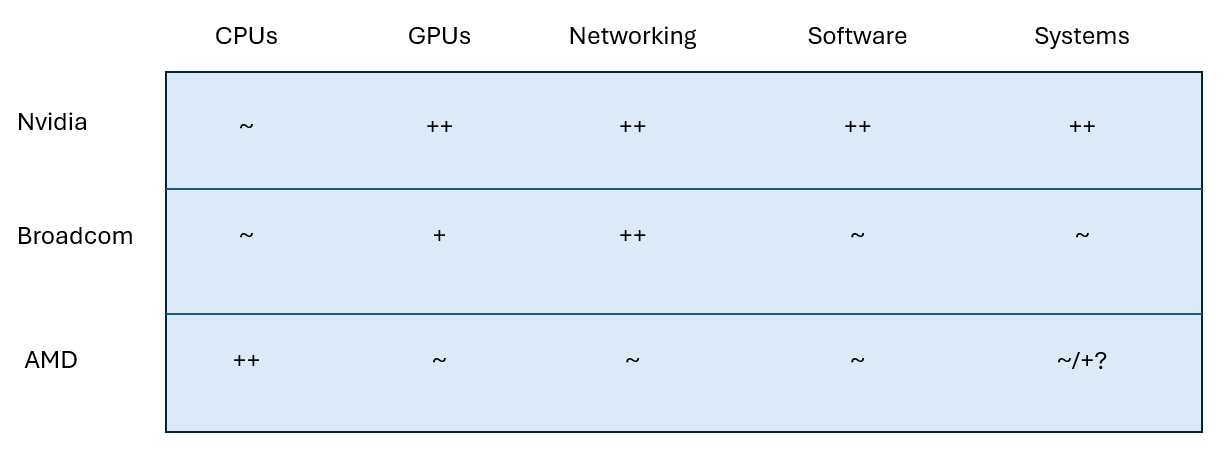

There was another layoff of around 15% of employees, a full dividend suspension (finally, guys), and a capex cut. At this point, it feels like an ambulance chasing to dig too deep and critique Intel’s results. I’ll call out some of the essential points, starting with WFE cuts, and then move my point to the broader point about platforms. The capex cut was light, and while some pointed it out as a bearish point for SPE, the reality is CPUs must be made, and many of Intel’s future CPUs will be made in Taiwan. They will purchase equipment, and WFE will essentially be the same. However, if you look closer, the real issue is that Intel sells almost 50 billion dollars of revenue annually and does not make much operating profit. The problem is that fixed expenses are incredibly high in a semiconductor business, and the operating overhead is likely way too large as the company unwinds. The reality is that x86 CPUs are irrelevant anymore and that Intel does not have much of a competitive advantage. ARM CPUs are coming from the client and data center. Intel’s competitive advantage doesn’t exist. Unwinds are just not graceful. Intel has been growing its revenue for decades, and now it has unwound to somewhere in the mid-2010s when it still had a massive competitive advantage. What’s worse is that the cost of revenue is meaningfully higher, and the operating expenses (employees, R&D) are also higher. As a corporate company, Intel must be sacked and run at a much leaner level than it is today. The painful and right thing to do is to cut expenses to the point where the business makes sense. This is no longer a tremendous American monopoly; a graceful unwind will hurt. It took almost a decade to grow the expense base from ~10 billion dollars a year to ~15, but now it has to react quickly as revenue drops precipitously. There’s no easy way to do that while pursuing a bold dash toward backside power at 18A. It’s time to cut deep and close to the bone. And maybe, in the words of a recent Redfin call, get in the trenches, drink urine, and thug it out until the Foundry business works. The bold leap towards the future will come at worse margins and with a worse competitive advantage than the Intel of Ole. And worse, if you look closely, no single business grows sequentially while competitors are. That’s share loss. Let’s compare the segment results of Intel (below) to AMD. AMD is growing sequentially, even in clients, and is booming in the data center. DCAI is losing share, and Intel has missed this platform altogether. AMD will likely sell more GPUs to AI companies than CPUs in the long run. Intel’s only hope is to lean into the manufacturing side, where it still has a relative advantage, and hope it can become a foundry. But let’s talk about Intel missing the platform and the party altogether. I think this nicely relates to AMD’s acquisition of ZT. Intel has Missed Not One but Two Platforms.Let’s take a minute to look at history. Intel has missed not just one but two big platforms in its time. The first was, of course, Mobile. It had a clear and early opportunity to be the company that could have ridden the mobile platform wave alongside Apple. There are many reasons as to why they lost, but the biggest one is this: x86. Instead of focusing on the future, Intel focused on its cash cow, x86. Intel has never done or concentrated on anything outside of x86, which was the reason for its extreme success in the PC era, its continued cash flow in the smartphone era, and its eventual death in the AI era. It’s almost the textbook case of the Innovator’s dilemma. Over and over, it focused on x86 while the world passed them by. The Intel you knew is now almost entirely dead. It will die with the incredible platform it rode the PC. Intel’s equity story, as I see it, is effectively dead. Equity is all about incremental cash flow and revenue; there’s no hope of that anytime soon. Managing a company in decline is different. It’s time to view Intel as an enterprise, not equity. This means that Intel’s manufacturing, CPUs, and other assets will continue, but likely after the long and painful road that breaks apart the monopoly that it once was. And this story is not precisely new. Instead of being broken up by the hands of regulators like Ma Bell, Intel is going a long way off the company that rode the platform before it, IBM. IBM, Intel, and Great Companies of OldFor some history, IBM was once the most significant American company of its age but slowly lost its way. In the 1980s, it was ~6% of the S&P 500. This was when you could safely say, “Nobody gets fired for buying IBM.” It was a household name synonymous with American technological success. Like Microsoft after, it had an Antitrust case that pushed it to subcontract the operating system to Microsoft in the 1980s. IBM was big blue and was the first fully integrated technology, from the hardware to software to the services that ran on top of its ubiquitous mainframes. However, IBM missed the significant platform shift, the change from business-led mainframes to personal computers. But by the time 1993 rolled around, the once-great company seemed to be an aging giant. As the computing platform shifted from the mainframe to the PC, IBM was utterly left behind by the early 1990s. Shares had dropped 75% from their 1987 high. Now, the story of IBM is probably too long for a single post. Still, for extracurricular reading, I highly recommend “Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance,” highlighting how Lou Gerstner did a culture turnaround and shifted the business from selling mainframes to selling solutions powered by mainframes. The IBM story sounds very familiar to the one that Intel is telling today. Intel was one of the key companies that disrupted the IBM paradigm of mainframes and was the critical chipmaker for the PC era. The Wintel alliance drove PC units from under 20 million a quarter to over 140 million units a quarter during its absolute peak. Intel was the gorilla of its time. I watched “You Got Mail” the other week, and I found this interesting reference in the movie of the rich old Birdie Conrad, who got her wealth by buying Intel at 6 ($1.5 split-adjusted). Intel was the cognitive referent for success in the 1990s, much as Nvidia or Mag7 stocks are today. It’s no surprise that Intel’s peak market dominance was at the absolute peak of PC units sold in 2013 or 2014, leading to the peak of smartphone units in 2017-2018. The PC cycle was a lot longer-tailed than the smartphone, but the reality is that Intel and x86 completely missed the smartphone cycle, but the continued longevity of the PC cycle was enough. The momentum of its continued dominance kept it afloat despite losing smartphones. But Intel is just a dead company walking. The Intel of Old is gone, and to miss not just one platform but two means that Intel is just not relevant in this new world of ARM CPUs or, better yet, Nvidia GPUs. To miss a platform shift is to relegate yourself to a zombie in the next era, but it took until AI took off to show how dead Intel was. Now, Intel is in the same space as IBM was in the mainframe era. And it’s no surprise that they have had a 65%+ drawdown. To miss a platform is death, and it's time that Intel realizes what it is—a dead company walking. IBM is likely the best-case outcome for Intel. IBM had to grow and change past its mainframe days, and in their case, it mainly consisted of consulting and software such as transaction services built on top of its mainframe processes. In the case of Intel, the theory would be that the acquisitions of Mobileye or Altera would bail it out, but in reality, it will just be the fledgling foundry business selling the service of making a chip. That’s a pretty horrible offramp from being the monopoly provider of a platform. But luckily for Intel, there’s a massive demand for a Western-based fab, and that is the way out. Intel will be lucky to focus on that, make the transition, and realize that it is not even remotely relevant in the world of accelerated computing. That sounds a lot like IBM. It’s starting to lose relevance even in general CPUs, as ARM CPUs are taking off in the data center, and AMD continues to run circles around Intel. Intel never crossed the chasm to the next big thing. This brings me to my next point on platforms: AMD. AMD bought ZT Systems so that It Won’t Miss the Next PlatformThis is a bit of a tangent thought, but it makes sense in the context of Intel. Nvidia is charging forward with system-level scaling in a way that is revolutionary and a new step for AI training and inference. Not pursuing systems scaling is like not adding a GUI in the PC Era. Rack-scale system architectures are going from a nice to have to a requirement in tomorrow’s AI architectures. AMD doesn’t have a choice. They are the me-too in this era like they were to Intel in the PC era, and they must do this to maintain relevance. It’s going to be expensive, but I think the cost of the acquisition makes sense. This is an acqu-hire that likely will be accretive quickly and help them not fall behind. This was not an optional choice, this was required to be relevant. They can sell the manufacturing business for cost and hopefully recoup the entire acquisition in pushing rack-scale solutions. Honestly, this is so much further-looking than what Intel is doing, which is nothing. Broadcom and AMD continue to fight it out for number 2/3 in the world of accelerated computing. But I think Lisa's move is the right one. Not pushing for systems is to relegate yourself to missing a platform. Consider this the scorecard for AMD’s market positioning. You have each aspect to be part of the accelerated computing era. ZT is a ticket to continue to make it to the system-level scaling era of AI accelerators. Another way to look at this is this simplified scoreboard. Since ARM exists, CPUs are the most commoditized part of this stack, and that’s AMD’s strength. But I find Nvidia’s positioning enviable, Broadcom’s second, and AMD is just trying to keep in the race. I think ZT Systems has a solid chance of having a real advantage over Broadcom for the first time. Broadcom is just focused on designing to customers' specifications, and while they are likely aware of system-level integrations, most hyperscalers bring their design. AMD can hop into second place, and ZT Systems is a real bet that could level this playing field. While it’s expensive, it’s the right move to avoid missing the next platform. Ironically, AMD has been number two to Intel for a long time, to the point that it’s always had to scourge for more relevance. The acquisition of ATI kept it as number two in the GPU game. As accelerated computing took off, AMD was incentivized to invest more and more resources into this new business. It wasn’t a company just trying to hold on to what it used to have. It will make all the difference; AMD will live as a player in the next game. Intel? Well, that’s just a great American company of the past and an example of what it means to miss a platform altogether. If you enjoyed this, please consider a free subscription or share this article! I’m not feeling great, but I’ll be at hotchips and get a few pieces out next week. Talk soon! You're currently a free subscriber to Fabricated Knowledge. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |