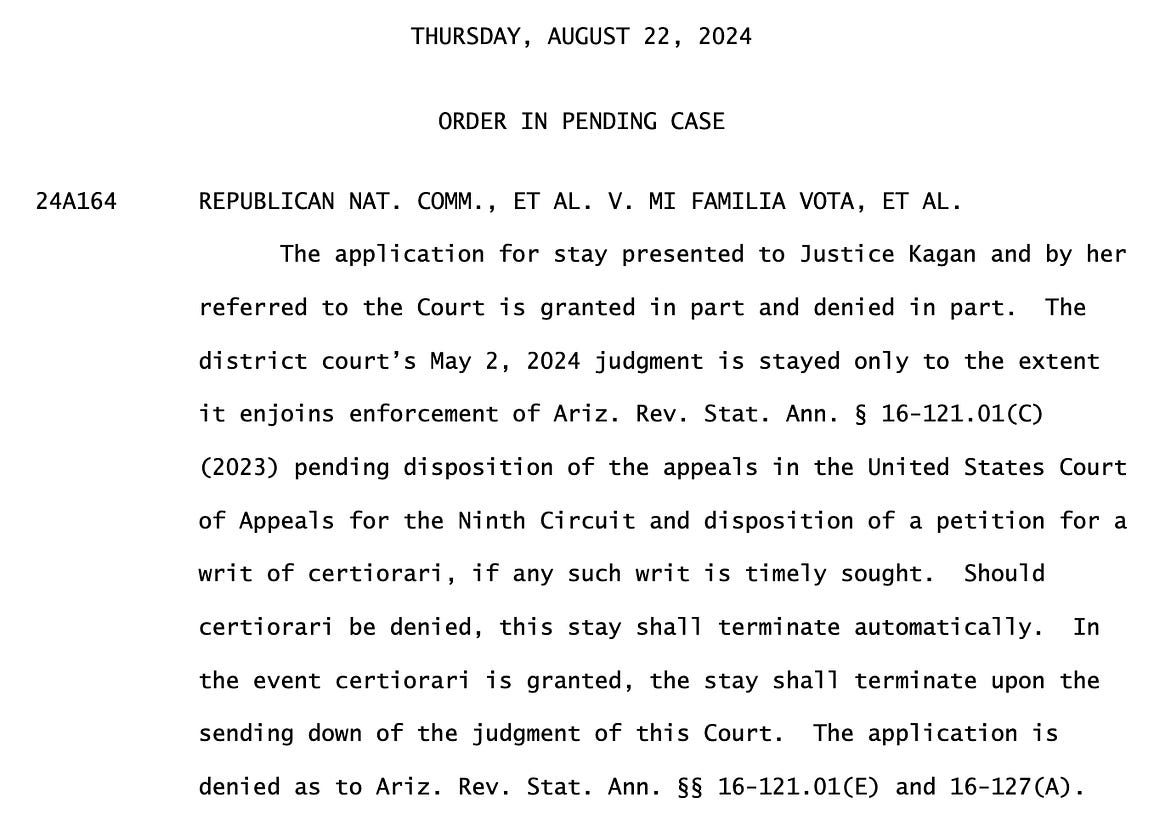

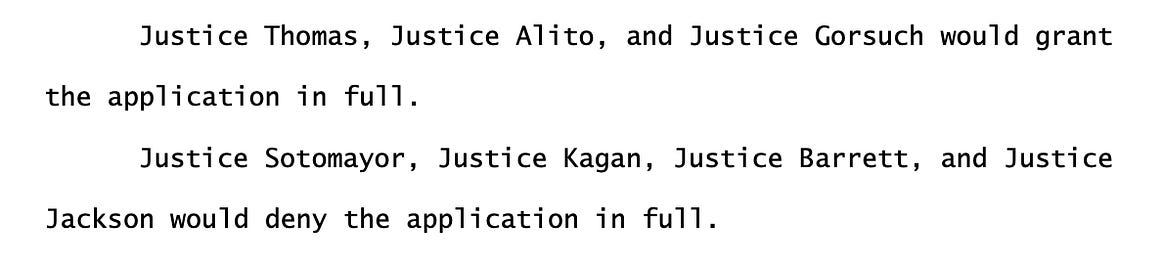

Thank you for being one of more than 36,000 people supporting Law Dork with a free subscription! I am so grateful to everyone for reading, subscribing, and sharing Law Dork. That said, my independent legal journalism does cost money to produce. Please consider a paid subscription, as little as $6 a month, to Law Dork today. If you do that, you’ll receive bonus features available only to paid subscribers — and support this essential reporting. I know that not everyone can afford it or prioritize a paid subscription, and, if that’s you, I am so glad you are here! Thanks, Chris This past week highlighted just how dangerous SCOTUS is on voting casesFive justices allowed last-minute voting changes. Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch would have allowed Arizona to enforce restrictions that clearly conflict with federal law.The conventions are done and the election is set. In the weeks leading up to Election Day and, perhaps, after it, the U.S. Supreme Court likely will be called to intervene in disputes — some raising legitimate questions, others potentially less so. The question for America is what the court will do. We got a hint this past week, and it was not reassuring. The Republican National Committee asked for multiple parts of a restrictive Arizona law requiring voters to provide documentary proof of citizenship to vote that had been blocked by a district court and, on a 2-1 vote, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to be made enforceable for this election. To be clear, voter registration forms require people to attest to the fact that they are citizens to vote. To lie on those forms would be illegal. If you are a non-citizen and lie, it could even lead to your eventual deportation. Despite that, Arizona, in a 2022 law, went further. One provision of the Arizona law will lead to a person’s voter registration being rejected if they use Arizona’s state form to do so and do not provide “satisfactory evidence of citizenship.” The other provisions would have blocked people from voting for president or by mail even if they registered using the federal form and did not provide that “satisfactory evidence of citizenship.” The federal-form restriction almost certainly is preempted by federal law, the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 — as the Justice Department clearly explained to the justices. The state-form restriction is troubling on its own, particularly due to the way in which it conflicts with an earlier consent decree in an earlier case — as Arizona Attorney General Kris Reyes made clear in her response to the request. The RNC, however, argued in its application that the earlier consent decree could not block state legislative action going forward. The Supreme Court voted on August 22 to allow Arizona to enforce the state-form restriction, but not the federal-form restrictions for this election. The court split at least three ways in its vote. The ruling as to the federal form should have been a 9-0 vote — and yet Justices Clarence Thomas, Sam Alito, and Neil Gorsuch would have granted both of the RNC’s requests. On the other end, Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Amy Coney Barrett, and Ketanji Brown Jackson would have rejected both of the RNC’s requests — likely an application of the so-called Purcell principle that counsels against courts ordering voting changes in the run-up to an election due to the confusion it would cause. (This also could be another example, at least as to Barrett, of her continued resistance to the use of the shadow docket.) Due to those noted votes, we know that Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh both voted to allow Arizona to enforce the state-form provision for this election. We also know that at least one of them voted to reject the RNC’s request as to the federal form. It’s possible that both of them did so, but only one of them needed to join Sotomayor, Kagan, Barrett, and Jackson to form a majority. The majority that voted to allow the state-form provision to be enforced — Roberts, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh — seemingly ignored the Purcell principle. Here, despite the court literally reaching different results as to different restrictions in the law less than three months before the election in an order that included no explanation, the word Purcell went unmentioned. There are 71 days until the election. What we saw this past week was not altogether surprising, as disappointing and dangerous as it might be. Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch are almost certain to vote for what the Republicans ask for. It’s hard to justify the vote that would have allowed enforcement of the federal-form restrictions in any other way. Even the RNC’s application is far weaker on that provision. We also seen that the Purcell principle will not stop Roberts and Kavanaugh from joining that trio when there is even an arguable basis to do so. And although Barrett joined with the Democratic appointees here, we have seen that she often will join the five other Republican appointees in much of their substantive rulings — even if she pulls back a little from the other five, as she did in both cases involving Donald Trump this past term. As such, and as with so many elements of our democracy today, the court will allow itself to be used as an arm of the Republican Party if and when they can convince Roberts and Kavanaugh that there’s a legal fig leaf to justify it. It’s not particularly uplifting, but the conclusion I reach from this is not that different from the conclusion many others reach as to Trump himself: The best answer for addressing this court when it comes to election litigation is by avoiding it altogether or ensuring that the only arguments that Trump and the Republicans can make are ones that are so bad that even Roberts and Kavanaugh can’t buy them. You’re a free subscriber to Law Dork, with Chris Geidner. To further support this independent legal journalism, please consider becoming a paying subscriber. |