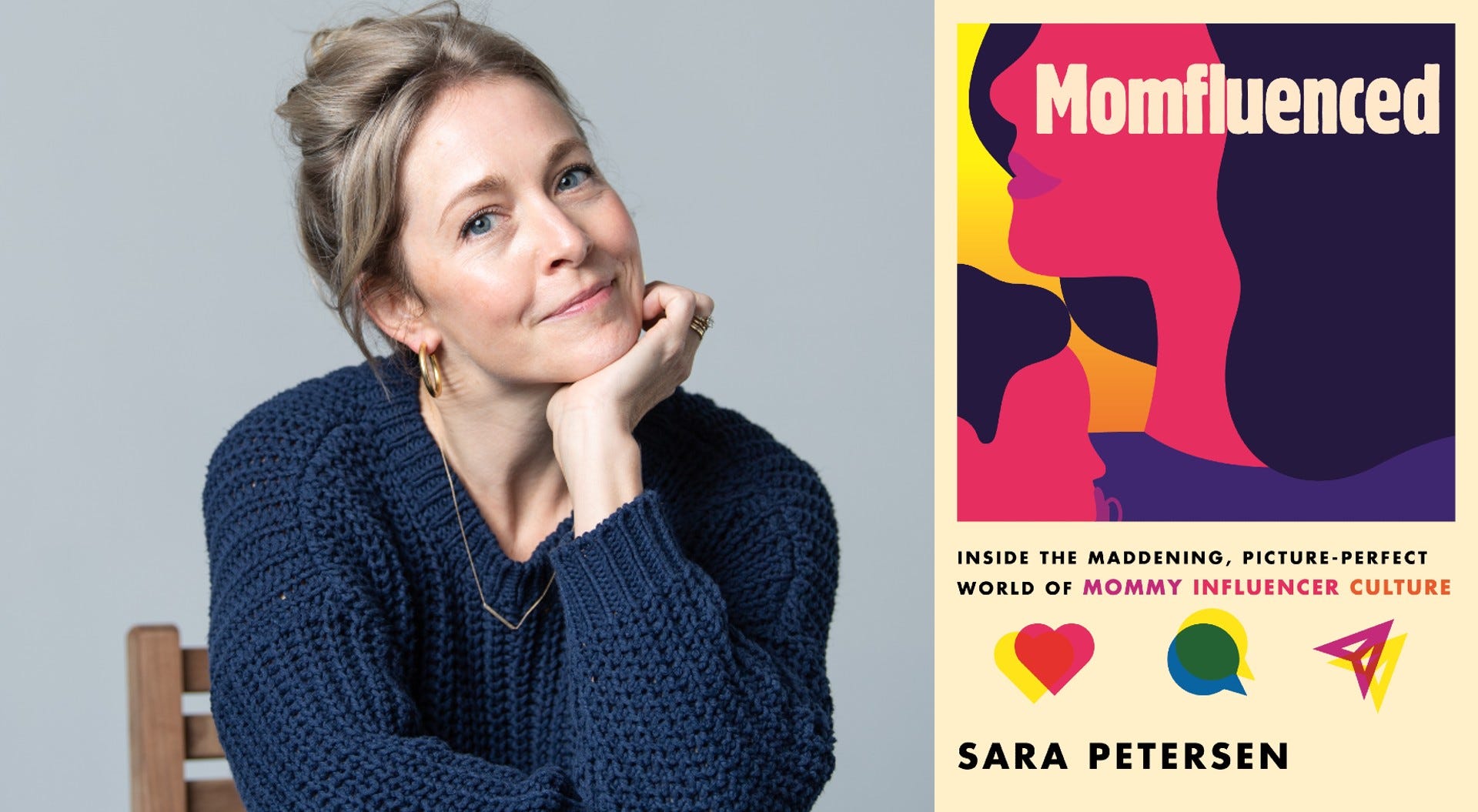

The momfluencer trap“These blissful versions of motherhood that are bought and sold on social media are more lucrative because so many American mothers are desperate to hope for something else.”Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, written by Kate Lindsay and edited by Nick Catucci. An earnest rec for my favorite momfluencer: Youtuber Rhiannon Ashlee. —Kate Sara Petersen and I first connected during a very weird time in my life. It was 2020, and if you can believe it, I was having a hard time. My way of coping was to go all in on a certain type of content creator: homesteading tradwives whose picturesque lives of homeschooling and baking seemed unaffected by the pandemic, as opposed to my life, which felt like it had entirely collapsed around my hallway of a Bushwick apartment. I wrote an essay about this obsession, which resulted in Petersen and I connecting for her book—Momfluenced: Inside the Maddening, Picture-Perfect World of Mommy Influencer Culture. The book is out April 25, but I got a chance to read an early copy, so can confidently encourage you to go here to give it a preorder. It’s been interesting to check in with Petersen‚ who also writes the Substack In Pursuit of Clean Countertops, every few years, as my own experience with motherhood presumably gets closer and closer. My relationship with that life stage is very much informed by the images of motherhood I consume online. The social media performance of motherhood can be extremely fraught, as my recent interview with Alexia Delarosa showed. But today, as Petersen emphasizes in her work, performing motherhood online is also inevitable. How do we go about navigating this public performance of something so universally encouraged but, in the U.S., so fundamentally undersupported? In this interview, Petersen and I talk about social media as parental validation, motherhood as an online identity, and the gateway drug that was Love Taza’s Naomi Davis (Naomi! We miss you! Come back!). How did you get on this beat? I've been writing about motherhood and feminism for several years. I didn't actually start seriously writing until I had my second kid. I started writing about motherhood primarily because I was constantly angry about motherhood and wanted to unpack my feelings. And then I started writing about mom influencer culture, again because I was trying to unpack my own feelings about the culture, trying to understand my own consumption of the culture. I started following a couple “mommy blogs” in like 2015 and [noticing] their representations of motherhood as being this rosy fun adventure versus being something that can be really monotonous, really thankless. I started writing about it to try to unpack that disconnect between maternal performance and presentation on social media and the reality of mothering. Was this your entryway into writing? I have a weird background. I was an actor first. And then I went to too much grad school and then I thought I was gonna teach. Writing is in my background, but I didn't study journalism or anything like that. What would you say was your first exposure to internet culture? My god. I think of stuff like AOL instant messenger and the dial up [sound], sitting in the hallway of my parents' house. I got my first email account for college to communicate with my freshman-year roommate. I still remember my old email address was based on my favorite candy of the time. Well, I have to know what it was. It was Junior Mints. And I had that email address for an embarrassingly long time. Like I applied to grad school with a Junior Mints email address. What came first: having children of your own or the mommy blog consumption? It was definitely kids first for me. I was very technology-resistant. I didn't get my first iPhone until I was pregnant with my first kid and I didn't start an Instagram account until like 2013, 2014. How did you end up discovering mom influencers and mommy blogs? I was probably Googling something to do with a specific kid-related problem, like traveling with kids, ways to entertain toddlers on a long flight. And then the big [mommy blogger] I'm thinking about is Naomi Davis. As soon as I found her I was all in. It just felt like a blueprint for how I might embody motherhood so that I was still the star of my own movie. I think one of the shocks of motherhood was that I no longer really felt the same sense of agency I had had, which is silly, obviously. I had plenty of agency. I had almost every privilege you can imagine going into motherhood, but there is just this erasure of self that happens, especially if you're not emotionally prepared for what it's gonna be like. I was trying to reclaim that sense of being the protagonist in my own story. Naomi is who I came to first, and it's so interesting that she was the gateway for both of us, but for totally different stages of life. What I was glomming onto was specifically the Mormonism of it all and discovering this world of Mormon bloggers and the very specific way they curated the images of their life. But also the agency aspect was interesting to me, too, because as I got older and became familiar with sort of the values of Mormonism ... to watch Naomi and that genre of bloggers in general become the breadwinners because of their maternal role and the way that flipped the script. So it was like girl boss, but also was it girl boss? Because it's still performing this subjugated role. I was definitely viewing them as if from behind glass or something. Yes. Because it is this uncanny valley thing where the labor of mothering is for the most part invisible and very private. And so to see this representation of motherhood that was so public was important because the visibility was the entire point. And when I really think about it, it's obviously foolish that I thought I could somehow replicate whatever it was she was doing in my own life without also becoming a mom influencer with thousands of followers. I think the whole performer-audience thing is so interesting when you think about mom influencers. Even if I had become a mini Naomi Davis and taken beautiful photos, if those photos were only for myself, I do think it would've done something for my sense of self, just looking at the photos and being like, this was my day and it was beautiful. But I don't know how far I can go without the external validation of thousands of Instagram followers. What would you say your social media presence was like, and when you started consuming this content, did you feel your presence change at all? I had no social media presence at all. And then I totally did start subconsciously and consciously replicating the style of posts, like zooming in on a kid's freckles and playing with the way the sunlight is hitting the subject. It a hundred percent impacted how I photographed and looked at my own motherhood. In this world where we're always presenting and branding ourselves, it can be hard to feel justified in doing it with my life as it is now. But I could go all in on posting about motherhood because that is societally important. We all agree that it's important. There are plenty of criticisms of mom influencers and it's a whole different kind of scrutiny that we'll get to, but in terms of the worthiness of what it is they're doing, that's not in question in a way that I feel like it is for anything else. I relate so acutely to what you're saying, but I felt that way when social media wasn't a thing. I was totally floundering in my career, but becoming a mother is an incontrovertible good. Nobody can judge that decision. I will have purpose and that will be my identity and I am assured success at least in terms of a worthwhile identity. Motherhood on social media is such a minefield and a big critique that gets leveled against these creators is that what they're showing is really not attainable. Is there an authentic way to post about motherhood that doesn't fall into these traps? I don't think anything we post on social media is completely removed from some layer of performance, no matter how much we want it to be. Like writing or sharing an image with like a single other person, there is an inherent performative element to it. Understanding that, I feel like centering conversations about individual experiences embodying motherhood. Like, this is what it feels like for me, and being really clear about, this is my specific experience and this is the context for my life. I think that's the closest we can get just being really transparent with where we're coming from. And centering the conversation on self. One of the big pitfalls of posting about motherhood on social media is that, more so than other things, if someone is posting their performance of motherhood, it is often taken as a judgment on someone else’s performance of motherhood. It's so fraught in ways like, how you feed a baby, how you wean them, whether or not their toys are colorful or beige. The presentation of one thing is innately seen as a really hard and fast stance and also judgment. I feel like that boils down to just a lack of support and resources. I would be really interested to see studies on Danish mothers, for example, and see if their feelings of internal inadequacy and comparison, if they were as high. I would bet they're not just because if you're operating from a deficit, and most mothers in this country are, you are going to enter conversations defensive and eager to prove that the way you're doing things is the right. We're all trying to prove to ourselves that what we're doing is the right thing to do. So much of it feels like a struggle and we get so little external assurance. How does social media play a role in that validation? So many of us are raised to think of motherhood as a) something we should automatically pursue and b) something we should automatically know how to do. When in fact it's not the case and we don't assume that of boys and fathers. We expect the dad to be bumbling with the diapers and whatever. But the mother is supposed to know how to do all this, which is absolutely ludicrous, like none of us do. And it's just so disorienting to be fed this narrative that motherhood should fulfill you and you should know how to do it and then push a kid, if you don't adopt, push a kid out of your body, not be supported by your government with paid leave, get one six-week postpartum checkup to see how you're doing, and then off you go. And then also motherhood is so optimized now. Our lunches have to be beautiful, our kids' bedrooms have to be aesthetically pleasing and be optimal for childhood development. We just are supposed to be operating at a 10 in every facet of our lives, so we're gonna look for guides for how to do it. What would you like the future of motherhood on social media to look like? I don't think it's a fresh point necessarily to be like, it's not real what they're doing. I think we all know that. I think we understand what influencer culture is. We are literate in that culture in a way that we weren't even five years ago. So just having just that base of literacy allows people to make more thoughtful decisions about how they wanna consume momfluencer content and for what purposes. Like I think even that example I spoke of earlier about Googling toys that will keep a kid entertained on a plane, that was a specific problem I was trying to solve. And I do feel like if we use social media for those specific purposes, we are probably less likely to get sucked into comparison spirals. At the same time we're also opening ourselves up to be more vulnerable and opening ourselves up to potentially harmful faux-expert advice. But I'm just so tired of any sort of belief in a maternal ideal. It'll take a long time, but I just hope we start operating from the knowledge that there is no ideal, that depending on our layers of marginalization or layers of privilege, motherhood looks and feels radically different for each of us. And that systemic support is necessary. And I do think that's connected to social media consumption because I think these blissful versions of motherhood that are bought and sold on social media are more lucrative because so many American mothers are desperate to hope for something else. And if we were less desperate and less in need of hope, I think that ideal would sort of fall flat and deflate.

|