2001 capaccess.com home page detail, via Wayback Machine

Today: Activist, musician, and writer jj skolnik; and John Saward, a writer based in Chicago.

Issue No. 152Community Based Network

jj skolnik Your Old Room

John Saward

This story is part of The Lost Internet, a month-long series in which the members of Flaming Hydra revisit internet marvels of the past.

I got my first email address from the public library. In 1992, with funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Georgetown University, a “community-based computer network” called CapAccess went online. For a one-time fee of $25, you could sign up at the library and get an email address of your own, access to an assortment of local bulletin boards covering life in the DC area, and a portal to a number of other early internet worlds, including other local “freenets” similar to CapAccess, Usenet newsgroups, and Telnet, which could take you to any other server in the world, provided you knew the address. My library account was a godsend, for a messed-up 13-year-old with a lot of problems who was a couple years deep into becoming obsessed with their local punk and indie rock scene. I could connect with other punks and DIY sorts through the local boards, Usenet, and mailing lists, of which I joined about 100. I shared a partially written mystery novel told from the perspective of the detective’s cat with a community of amateur mystery writers, who refused to believe that I was in junior high. Through Telnet, I explored early roleplaying sites—MUDs and MUSHes. I wasn’t super into the roleplaying aspect of it, but I liked hanging out in the “out of character” (OOC) rooms, where I could just talk to random people from around the world. Sometimes I’d meet up with a good friend of mine I’d grown up with, like me an early online adopter, to chat long past our supposed bedtimes. Which is how we met two other teen punks from California; one of them became my friend’s long-distance boyfriend, and the other became my best friend, and my roommate on and off through the years as we became adults. Twenty-seven years later, I’m still close with him—the longest continuous close friendship I’ve had. The Usenet group I frequented most often, alt.music.hardcore, spun off into a bulletin board when the web came around, and that bulletin board grew into a strong community of its own, through which I made many lasting friendships. Freenets exemplify the curious and democratic spirit of the early internet. Anyone could get online for a very reasonable price—and you could sign on at the library, too, for people who didn’t have computers at home (or a home to go to). It opened up access to an incredible amount of resources, knowledge, and connections. You could search and apply for jobs, learn what was going on in your community and communities beyond, and join any number of niche discussions on any interest you might have had. This was the internet I fell in love with. I could even talk to people who sympathized and understood about the darker things I was going through that I was afraid to tell a lot of people in my offline life about—sexual assault and its afterlife, substance abuse, disordered eating. The internet was smaller in those days, much less commercial, and much more personal. Not without its many problems, but a space in which there was possibility. Freenets also represented, for me, the importance of public libraries as a repository of knowledge and connection. My mother went back to school to become a librarian when I was a kid, and libraries have always loomed large in my life—for a kid who was bookish and shy, who learned to read early but lagged behind in a lot of other areas, there was no better place. My real life, while my parents did their best, was full of mundane horrors. The library represented safety and escape. Today, public libraries are still a shining beacon, offering access not just to books and internet terminals but to a real third space. In today’s internet, it’s hard to find a corner of the world that isn’t gated and isn’t plastered with ads. But my local libraries now offer free fentanyl testing strips and naloxone, language lessons and punk shows, book clubs and conference rooms for community groups who need them. Information access, well-kept public archives, and community space are necessary for any functioning society. It’s no wonder they’re such a target of the right, and no wonder they’re so in need of support. If you don’t have a library card, go get one. And use it. CapAccess became managed by WETA, the local PBS station, in 1995. It lasted a shockingly long time, until 2009, when the ubiquity of free email services like Gmail and the rise of smartphones rendered freenets a thing of the past. A public good, made possible by PBS’s continual funding by the federal government, eaten up by corporations. Let their memory be a reminder of why such things are precious and in need of constant defense. And let’s not cede what remains.

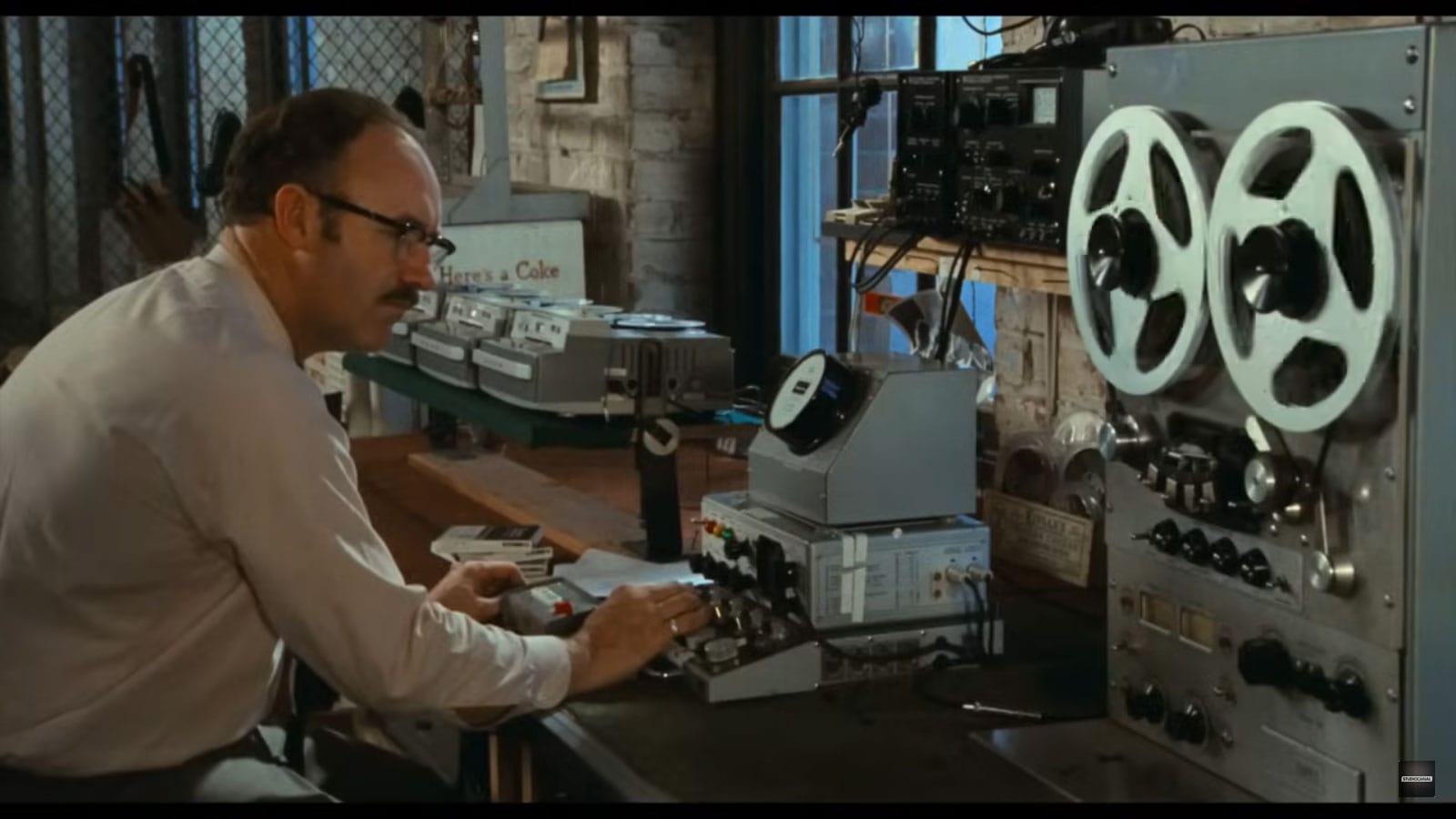

SHHHHHHH Screenshot: YouTube In her latest Guardian column, Flaming Hydra Arwa Mahdawi has some revelations regarding what everyone already knew: our phones are listening to us all the time. Bonus scary thing: “targeted dream incubation.”

Your Old Room Image courtesy of the author Here are all your retired sweaters, your D-list T-shirts, the jackets you bought with ambitions of becoming a Different Guy. Here is your dad’s old rec league hockey jersey, here is a slate grey dress shirt with this very strange and near-reflective sheen, which you wore to a bar in Hoboken one night after college, an almost repellent sheen honestly, but on that night you were a man with a big evening laid out in front of you and you were happy to wear it. All of it is in there, this mausoleum for all the different past versions of yourself, dumped in here between apartments. Here is an Albert Belle bobblehead and an Albert Belle action figure, here is a Rodney Hampton rookie card, here is possibly every piece of Albert Belle memorabilia ever made, in fact, each of which you can now see failed in capturing his simmering, remorseless brand of beefed-up sluggery. Here is the empty bottle of Mionetto that you bought for the 20-year anniversary of the bar where you worked, that you drank out of a little plastic cup with everyone who was in there while the sneering, trudging old grouch who owned the bar watched us and seemed to be having a rare and brief but genuinely nourishing moment. Here is a post-it your mom left you about going to the grocery store, back in a little while, which you kept just to remember what her handwriting looks like, and a photo your dad took of the dining room with the midday sun coming in through the back windows, a particular atmosphere you associate with a forbidden kind of leisure and freedom, home “sick” from school at 3:00 p.m. in an empty house. Here is Kim Kardashian’s Selfish, inexplicably, a Sandy Koufax biography, books that you didn’t and don’t know what to do with, hefty anthologies you bought for a college class, The Complete Piano Player: Omnibus Edition. A book called Heart Advice for Difficult Times, which someone gave you because you were dealing with what you would have to describe a difficult time, just a hideous and calamitous period, for no reason in particular besides that you were 26 and that’s just what you were doing back then, lifting all your little dramas to such a ridiculous height and volume that an onlooker might say, this guy could use a book written by a Buddhist nun about chilling the fuck out. And so that is in your bedroom too, because why would you take something like that with you when you move? And here are all your CDs, the cases with cracked and foggy plastic, three Built To Spill albums, Willenium by Will Smith, which was the first CD you ever bought with your own money, and a mix CD with an unconscionable amount of Iron and Wine. Here is Born To Run, which you took from your dad’s shelf one summer when you were in high school and listened to over and over while you played TimeSplitters 2 on PlayStation, every song big and desperate and looking for a way out of here. And a few years later when you e-mail an older music writer you admire you will describe that exact scene, as a way of building a narrative, only you will replace Bruce with Interpol’s Turn on the Bright Lights, all of which is enormously and horrendously embarrassing to you even now, but Bruce you had worried was the music of saps and dads, naïve romantics, men who were thinking about motorcycles but not men who were riding motorcycles. Interpol was “for real” (believing you’re the first person ever to be depressed on a subway train). They were skinny and acting ambivalent about their ex-girlfriends and they were making a career out of it. They were mostly privileged kids who went to NYU who nonetheless sang like there was some critical emergency in their lives. Their lyrics never revealed or described much at all, but being indecipherable was the point; being desperate and earnest was for suckers. They were sort of fraudulent but then again so were you. Most importantly they were what was prescribed for “complicated” men at the time by websites who might presumably pay you for your Ideas. Websites! Betraying your life for a website. Imagine? But the thing is you have been listening to Bruce your entire life, just about, while the book by the Buddhist nun never made sense to you and all those jackets only ever made you feel uncomfortable. Here is the chorus of “Backstreets,” tragic, ridiculous, heroic, making maybe too big a deal about itself in a purely mid-20s kind of way. Here is the saxophone solo on “Jungleland,” which has no delusions at all about the kind of mood it's in. Here are all your shames and glories. Here is some heart advice for difficult times.

Send this Hydra around, and ask friends to subscribe and donate. Preserve a world in which regular people can talk freely about what is going on, and many-headed beasts breathe FIRE.

|