When Sarah Smarsh writes about the heartland, she’s writing about her own heart.

So much of her writing works to undermine the JD Vanceian narratives that portray poor white people in America as lacking initiative as well as education. In her essay “Poor Teeth,” Smarsh wrote that it was lack of access to jobs with health insurance that prevented her and the people in her family from getting dental care. She wrote, “Such marginalization can make you either demonize the system that shuns you or spurn it as something you never needed anyway. When I was a kid and no one in the family had medical or dental insurance, Dad pointed out that those industries were criminal — a sweeping analysis that, whether accurate or not, suggested we were too principled to support the racket rather than too poor to afford it.”

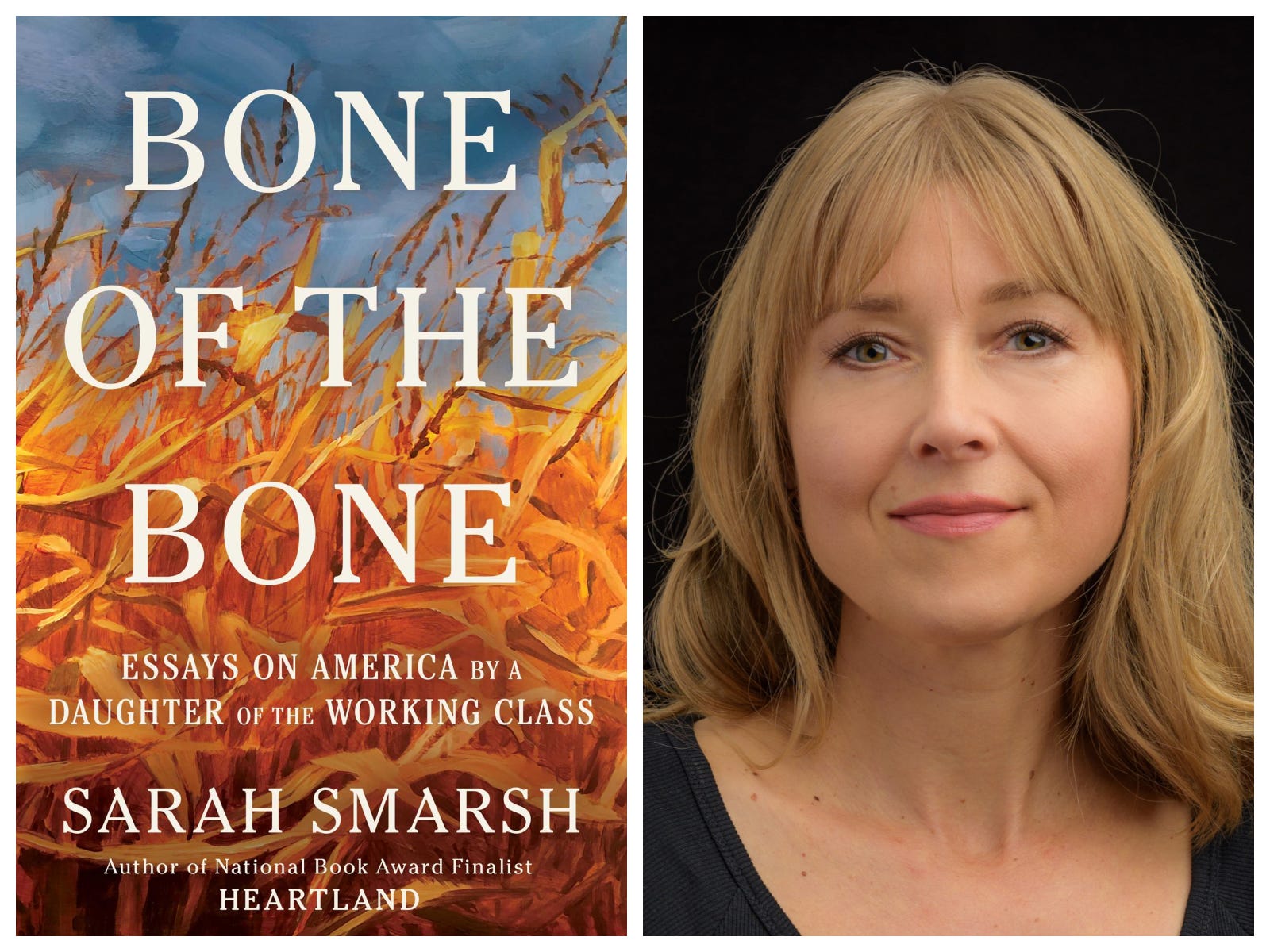

Smarsh’s book Heartland was an instant New York Times best-seller and a finalist for the National Book Award. Her most recent book, Bone of the Bone, is a collection of her work, some new and some previously published, that together offer a portrait of Kansas and other flyover states that complicates the narrative of angry men in diners. Yeah, men may be angry, but so are the rest of us, and how that plays out is far more complex that the red vs. blue maps account for.

I talked to Smarsh about her new book, her frustrations with “liberal blind spots” and the path to reclaiming America.

Buy Bone of the Bone

Lyz Lenz: I want you to at least take a stab at defining this amorphous middle space of America that you write from. In what space are we writing from? What makes you a Middle American writer?

Sarah Smarsh: Well, for me, there are a few threads that have to be braided to answer. One is geography and the fact that I'm not only from Kansas, which is the literal center of the contiguous 48, but I actually live there. And that makes me an outlier of place in terms of the media industry that I'm part of.

So many of my immediate colleagues in media and publishing have just about only ever literally flown over the place that every day I put my feet down on the earth. That's an aspect of my identity and my work that's paramount.

And then within that space, there’s another layer about my unique advantage as a writer, which is that I was raised among the rural working poor.

And that demographic, specifically the white rural working poor, has become synonymous with a particular sort of politics by way of narratives largely crafted by people who do not know that demographic or that place firsthand.

I'm challenging the pat narratives and stereotypes about that place, which is much more complicated than it is conveyed.

In addition to geography, we've got class. I would also add my gender. To be a woman that is speaking from this place and from that class experience is also a little bit of a disruption in the national discourse in that these same stereotypes that I'm writing against are often, you know, the white man in the hard hat.

Now, my dad happens to be a white man in a hard hat, a construction worker. He's also a progressively minded person. But for me, as a woman, I'm often addressing what I think are blind spots about the class experience along gender lines. So my place, my class, and my gender all kind of intertwine to hopefully offer a voice from flyover land that is relevant to our cultural moment.

LL: I do want to talk about that cultural moment. One of the essays in the book about liberal blind spots, specifically as they relate to “flyover” land. What are those liberal blind spots and why do they exist?

SS: That essay for the, which I wrote for the New York Times in 2018, was really responding to a moment within the media industry, when was a lot of these sort of, like, safaris into the red hinterlands to talk to Bubba wearing the MAGA hat at the diner. And even that has now become a cliche.

And I think there's been some improvement in political coverage and talking about that particular, the Trump phenomenon.

But when I wrote that essay, this was a peak problem of parachute journalism, in a way that I took quite personally, because my family and beloved are members of the white working class and not Trump voters.

And that's true of about one in three or sometimes even 40% of people in any given “red state.”

That “liberal blind spot," as the Times headlined it, was referring to what in the essay I assert is a lack of understanding by way of lack of direct experience. So if you're a very well meaning reporter and skilled journalist who has only ever lived in a major city on one of the coasts and doesn't know anyone in the middle of the country and has hardly ever gone there — maybe there were a couple professional conferences in Chicago —

LL: Yeah, they came to Des Moines for the caucuses twice and never left the city, except to go to Ankeny.

SS: There is culpability in that, a lack of awareness of the blind spot. And that blind spot often involves classism. It often involves what I'm going to call placeism, and it's utterly unchecked.

There are other aspects of American identity that we are now, thankfully, having open, important conversations about — addressing racial and gender injustice. But we still are just really clunky at talking about these other aspects of marginalization that are true for millions of Americans. For example, wealth inequality, lack of access to education, or health care.

This marginalization involves living in a place where you're 40 miles away from a hospital, let alone down the road from, you know, some sort of power center of the media or government.

We all have blind spots, but what I think is objectionable — and willfully, at this point, insulting — to presume that you could swing by the diner and now tell the rest of the country about all of Iowa or all of Kansas, and that electoral college map will tell you that it's a red state.

The blind spot is that everyone in the “red state” is homogeneous politically. It's lazy and it's inaccurate. And I can bear direct witness to that because I am from that place, in that class. In 2016, more people caucused for Bernie Sanders in the Kansas primaries than did for Donald Trump. That's a fact.

That sort of populist energy that has been artfully leveraged by the right is true, or at least at one point was also true, on the left.

And then, of course, there are all the gray areas in between and the center and the independents and the swing voters.

There are political trends, yes, but that is not the same thing as the simplistic narratives that are trotted out to explain a place in a movement which, by the way, has been created and led by very rich, very formally educated white people. At the heart of my critique is also that we're not talking about, even if it was true that every poor, rural white person in this country was a Trumper, where is the conversation about all the wealthy and middle-class and suburban white people who, by the millions, put this man in office?

I don't read any stories about that.

“At the heart of my critique is also that we're not talking about, even if it was true that every poor, rural white person in this country was a Trumper, where is the conversation about all the wealthy and middle-class and suburban white people who, by the millions, put this man in office?” — Sarah Smarsh

Share

LL: This frustrates me so much. There is this idea where people are like, well, y'all got Trump elected, so you deserve this. And I'm like, Trump was not forged in the fires of the Midwest. He was made in New York.

And let’s not pretend that voting is some accurate representation of a state. Wisconsin is one of the most gerrymandered states in the country. It’s a problem to write off an entire demographic of people based upon the color of their electoral votes. Where is a real, honest conversation about power?

SS: I think that as a culture and as a nation, we have to grow up and acknowledge that multiple, seemingly competing truths can exist simultaneously.

Here's an example. Kansas has gone for the Republican candidate in a presidential election for so many decades that it's now considered “ruby red” in national politics. Also true: Kansas held the first ballot measure after the overturning of Roe v. Wade during a primary in August 2022, when conservatives in the state legislature were basically trying to pull a fast one on the Kansas people, assuming that few people would be paying attention to that race, especially because we have closed primaries here in Kansas. Democrats often don't have anyone to even vote for on a primary ballot, so they don't even bother.

The “fast one” was a move to essentially undo or make way for the undoing of the right to an abortion being enshrined in our state constitution, as had been recently affirmed by the state Supreme Court. A coalition of Kansans, including progressives, moderate Democrats, Republicans, independents, previous non-voters, all colors, urban, rural, joined forces, engaged in some hardcore boots-on-the-ground rallying. As a result, the state of Kansas voted down that amendment.

It caused shockwaves throughout the nation. How could it be in red Kansas? And it goes back to these under-discussed political minorities.

And so to me, this is proof of what I'm often arguing, which is that there's a distance between the way we talk about politics and sometimes even the way that people identify politically and what is actually true in their belief system.

And when someone came along and knocked on a door and earnestly said, “I don't care who you vote for, if you care about freedom, how about the freedom of your teenage daughter to get an abortion if she's raped?” And that person went to the ballot and voted fuck no. And that then became a playbook for the Democratic Party across the country to hold off the predicted red wave in the general midterm election a couple months later.

And it remains a major strategy now for the democratic ticket running for president. So I find it ironic — and personally delightful as a proud Kansan — that that coalition of Kansans in this “ruby red” place, by successfully defeating that amendment, created such a ripple effect that it might do no less than save our democracy come the November vote.

To sit in a blue state and claim that you're engaged in some sort of cultural welfare with your taxes to red state people — check where your food comes from, check where your natural resources come from. Check who's fracking the hell out of North Dakota so that you can have a plastic-coated menu at the diner. Check who is drilling oil so that you can drive a car. Check who is working in a wheat field so you can eat a piece of bread.

“To sit in a blue state and claim that you're engaged in some sort of cultural welfare with your taxes to red state people — check where your food comes from, check where your natural resources come from. Check who's fracking the hell out of North Dakota so that you can have a plastic-coated menu at the diner. Check who is drilling oil so that you can drive a car. Check who is working in a wheat field so you can eat a piece of bread.” — Sarah Smarsh

Share

LL: Here's a question I hate, so I'm gonna ask it of you. You can fight me if you want to reach through the phone and punch me in the face, but here it goes: “How can those people vote against their self-interest and vote for Donald Trump? “

SS: So that particular idea comes from Thomas Frank, who wrote the seminal political critique, What's the Matter with Kansas? about 20 years ago. This was pre-Tea Party, but there was already a palpable rightward swing in certain corners of the middle of the country.

But I think his critique missed the mark in a lot of ways. If you're saying that people vote against their best interest, you're implying or you're stating indirectly that they're stupid, that they're gullible, that they're ignorant. So the question, “How could they vote against their best interests?” is actually, “How could they be so stupid?”

And that critique was wrapped up in the notion that cultural issues have been leveraged at the expense of good economic sense.

So a person who is a devout Catholic, for whom abortion is the No. 1 issue, will vote for the “pro-life” Republican Party even at the expense of their own pocketbook, when Democrats have better policies for economically struggling people.

I'm not going to say that that's never happened, but I think that to reduce everything to that framework misses a lot of important pieces, and it misses the culpability of the Democrats in this whole conversation.

Let's talk about NAFTA. Let's talk about where resources have not been invested because they have been employed strategically for the electoral college and left a lot of people feeling like they haven't seen a Democrat knock on their door in decades. Let's talk about the rise of conservative talk radio in the 80s, the rise of conservative cable television propaganda in the 90s and into the aughts.

Let's talk about social media strategically targeting particular demographics who have not been directly looked at or addressed or validated — particularly in their class struggles — by the Democratic Party for a really long time.

And in that void of concern the far right faction swooped in.

I am not suggesting that the people who then “fall for” far-right messaging are stupid. I think it suggests that they're human beings who need to feel validated on some level. And I don't want to discount the white supremacy and the racist undertones and implications that a lot of this phenomenon employs. But I think that simultaneous with that truth is real pain, real lived disadvantage.

Democrats just really fumbled the ball on that. Somewhere around the Reagan era, I would say that Carter was the last person that was really talking about it.

And in the 90s we got “free trade.” By then, the farm crisis had gutted our agricultural communities. Now industry falls as well. There's a lot of resentment. There's a lot of real pain. There's a lot of real struggle.

And who spoke to that pain? Politics is an emotional business before it's a rational one.

Sarah’s book Bone of the Bone is on sale now.