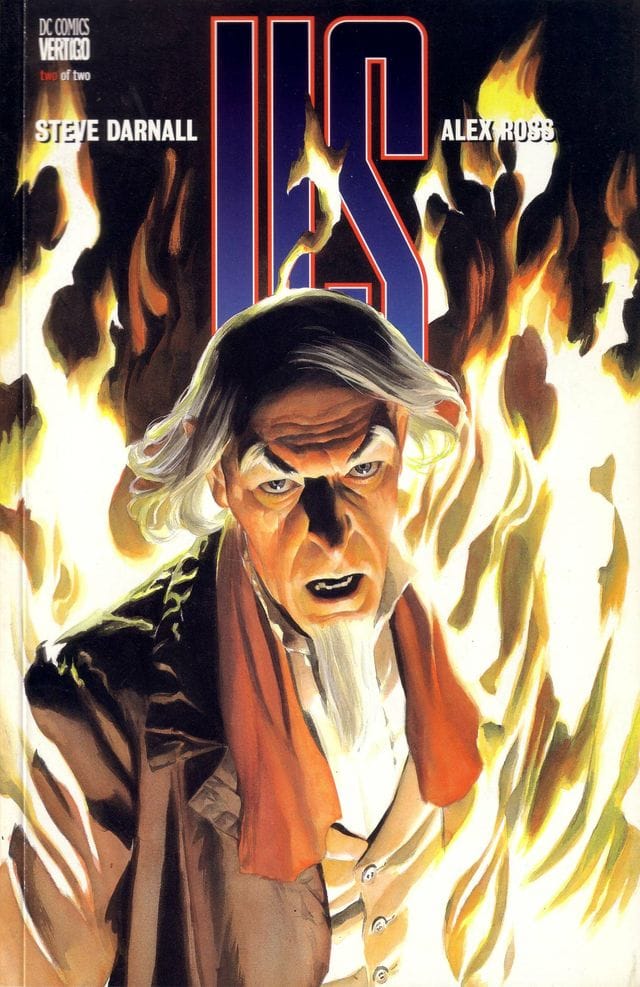

Cover of U.S. by Steve Darnell and Alex Ross

Today: Josephine Riesman, New York Times-bestselling author of Ringmaster and True Believer.

Issue No. 156Uncle Sam Deserves a Better Country

Josephine Riesman

Uncle Sam Deserves a Better Country“No! I will never apologize for the United States!” he screams. His skinny body is restrained by hospital orderlies; he is clad in a tattered yet instantly familiar suit of red, white, and blue. His white beard and dramatic eyebrows flail with emotion. Uncle Sam is having an episode. A doctor tries to intervene: “Sir, please understand—” “I don’t care what the facts are!” he yells, wild-eyed. “Gridlock!”—“Message: I care!” “Uh, I’m sure you do, sir,” the doctor says. And then, a moment later: “There’s nothing we can do for you.” “I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever—we begin bombing in five minutes!” Sam howls as he’s dragged out of the hospital. Such is the America of Steve Darnall and Alex Ross’s visionary 1997 graphic novella, Uncle Sam. Which is to say, such is our America: a 250-year-old idea on the brink of death and begging for help. And it was our America in the ’90s, too. Signs and portents. Symbols and icons. Legends and myths. The time is right now—today, this very moment—and the top-hatted embodiment of the United States is living on the streets. Good ol’ U.S. is down and out. Out of print for decades after its initial run with DC Comics’ Vertigo imprint, Uncle Sam was released last month by Abrams Books in a gorgeous new “Special Election Edition”, and it does, indeed, feel eerily relevant as the battle for the White House trudges on. But in re-reading Uncle Sam and speaking to its creators, I couldn’t help but think about it in the context of 9/11’s twenty-third anniversary. Post-9/11 Americans are all victims of myth. We, the People, were attacked by Heaven-oriented fanatics, and then we were “defended” (by which I mean surveilled, detained, and imprisoned) by true believers in things like patriotism, capitalism, and their own Heaven. These visions coalesced into a war that left American politics and much of the Muslim world a cratered, cynical wasteland. There were a few who tried to stop the bloodshed, but those resisters didn’t stand a chance. They were fighting passionate belief with reason, and that never works. If only the antiwar movement after 9/11 had read Uncle Sam. It contains what might be the ultimate truth of politics: The only thing that can stop a bad guy with a myth is a good guy with a myth.

I am a Millennial. When I was a teenager, all of the cool adults I could relate to were Gen Xers, and the ones who had the biggest impact on me were the anti-sweatshop activists and the comic-book storytellers. So this is an elegy for the political left of my babysitters’ generation. The activists hooked me at a weekend presentation in my middle school. They’d brought displays and petitions about the slave labor that went into the clothes I wore. I felt utter horror that I had benefited from such injustice. The scales fell from my eyes and I signed up to be an anti-sweatshop / anti-globalization activist myself. Around the same time, I was getting serious about comics. I’d read a lot of Marvel superhero nonsense and licensed Star Wars tales, but only in early adolescence did I start to read more ambitious fare. I don’t remember how it happened, but at age 12 I stumbled upon Uncle Sam in its initial release. It wasn’t a superhero saga in any conventional way. It was a surreal journey through the horrors of the U.S.A.’s past and present, rendered with Darnall’s jarring words and Ross’s photorealistic painting. Uncle Sam wanders the streets of an unnamed city, occasionally finding himself transplanted into scenes from America’s past, most of them shameful: Native genocide, chattel slavery, class warfare, and the like. He meets walking symbols of other failed empires: the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union. Over and over, he is shocked to learn how much his country has failed its own people. I had never experienced a comic book—hell, any kind of book—that was so brazenly and fastidiously critical of the United States. I tried to tell everyone I knew that they needed to read this comic. I even gave a copy to my Social Studies teacher. He said it was pretty, but underwhelming. I felt like I was shouting into the void. In the late 1990s, a preteen raving about the injustice of the 1791 Whiskey Rebellion had just about as much effect on society as, well, a homeless man raving in an emergency room. In 1998, the two issues of the comic were collected into a bound edition, and I eagerly attended a signing event for it in my hometown of Oak Park, Illinois. I got my autographs, assuming that there must have been countless kids across the country like me out there who were seeking Darnall’s and Ross’s guidance at events like this. But when I spoke with them last month, and asked them if they’d had lots of people coming up to them at signings and thanking them for their book, as I had, I learned they shared my feeling of being ignored, back then. “You were the exception by virtue of actually coming up to us,” Darnall told me with a self-effacing chuckle. “People were very shy about their affection for Uncle Sam.” There’s a lot about the United States, and about democracy, that’s great, Darnall told me. But when the book was published, “It was still a time when the idea of any work that took a critical eye of American history might be viewed with some suspicion. There was the whole ‘love it or leave it’ attitude…And that’s the sort of thing that the book was meant to address.”  Thumbnail of National Comics No. 3, September 1940 (image via Wikipedia) Darnall and Ross began working together when they were both living in Chicago around 1990, and hanging out at a local shop, Comic Relief. If they ever got to make a comic together one day, they agreed, the 1940s comic starring Uncle Sam—a scrappy superhero—was an inspiration they’d pursue. Ross also had a concept for a painted, realistic comic about the full sweep of Marvel Comics’ decades of mythmaking. Darnall wrote a script for a teaser about the original Human Torch. Marvel loved it, but they wanted a more established writer than the amateur Darnall. The end result was Marvels, one of the most acclaimed comics of the ’90s. Ross became a superstar, and Uncle Sam went on the back burner. But eventually the time was ripe; Ross now had enough cachet to get DC on board, and the duo dove in, poring over through revisionist historical texts and thousands of depictions of Uncle Sam. Darnall interviewed Alan Moore, the venerated British magician and comics writer of revolutionary works like Watchmen and From Hell, for the magazine Hero Illustrated. Moore was elated by the Uncle Sam idea, and later gave Darnall a whole reading list, nonfiction and fiction, about Uncle Sam as a political and literary symbol. The resulting narrative was loose and jazz-like, filled with evocative snippets of dialogue from American political rhetoric (Darnall compared it to hip-hop sampling, though one can also draw parallels to the experimental cut-ups of novelists John Dos Passos, Thomas Pynchon, and Robert Coover—all likewise critics of America). Sam’s antagonist is another Uncle Sam, one who is well-dressed and confident, who appears at conservative political rallies, who sits atop a throne of TV sets and says things like, “I’m ending welfare as we know it while building a bridge to the twenty-first century…So why don’t you just go back to your cardboard box, okay?” The book was released in its two parts. The critics loved it; comics fans greeted it with a shrug. Uncle Sam was the victim of the same hyper-patriotism and apathy that afflicted its hero. Reactionary conservatism was on the rise, and liberal complacency was at an all-time high; the Rush Limbaughs and Bill O’Reillys of the world were still laughingstocks who could be safely mocked by the likes of Keith Olbermann, whose first show on MSNBC debuted that year. Conservative readers were turned off by the book’s accusations against their country; liberal readers, for whatever reason, were unmoved. Still, the critical success led to some awards, and even as it fell out of print, Uncle Sam’s afterlife continued. There was talk of a sequel in which Sam faces down Hitler, who is revealed to have never truly died; DC felt it was too much of a downer, and that fascism no longer posed a threat. Back to the Future director Robert Zemeckis wanted to adapt the book into a movie, going so far as to take a meeting with Darnall and Ross, but that project fizzled out, too.

When the first plane hit the World Trade Center, I was in my tenth-grade geometry class in suburban Chicagoland. I could tell the world had changed, but I didn’t realize how tight the vise was about to get until about a week later, when I went to the first post-9/11 meeting of Students Against Sweatshops, my teen labor-rights group. Our Gen X adult adviser told us that the antiwar movement was about to take total precedence over every other issue on the left. I was gutted. We’d been pushing for proactive change, and now we’d been forced into a totally reactive position. “Oh, and also,” our adviser said, “you all have to be more careful about communications. The FBI is going to be listening in now.” But the feds weren’t the only reason the Gen X leftists lost their battle. Just as critical was the lack of an animating myth. The dream of the ’90s left, as I experienced it as least, was fundamentally an anarchistic one: no gods, no masters, no plan, no participation. In the wake of Communism’s death, there was no single goal that masses of leftists wanted to unite to glorify and achieve. My own activist teachers (most of whom, it is important to say, were white and upper-middle-class) were part of a largely critical movement, rather than a constructive one. The closest the Xer leftists in my circle came to a positive program was backing Ralph Nader’s disastrous third-party run in the terrible year 2000. Their critiques of society were legitimate, but critiques can’t build a movement, or a nation. For that, you need dreams, big ideas—myths. A myth is not a lie, per se—it’s an unreality that can shape reality. The right understands this, and they traffic in extremely potent myths; myths that withstand all fact-checks and accusations. Unlike most of the radical left, the radical right truly believes that America is an idea worth saving—it’s just that their idea of “America” is an abhorrent one. Why not fight it with our own myths? That is the message of Uncle Sam. Perhaps it can find a following now, in an age when criticism of America is again de rigueur on the cultural left. Maybe there will be more kids like me, kids who weren’t even born when 9/11 happened, who will feel the scales fall from their eyes upon reading it.

I’ve had a long-running argument about patriotism with my spouse, the writer S.I. Rosenbaum, who told me she was a patriot. I said patriotism was the last refuge of the weak-minded, and she replied that she isn’t a patriot for the government or the Constitution. She’s a patriot for the other America. She centers the oppressed Americans who have survived and changed America: poor immigrants like my great-grandfathers, the descendants of enslaved people, the unhoused, the queers, the religious minorities. She is a patriot for their America. And that other America, the one that doesn’t write the headlines or produce the TV shows, has always been making art like Uncle Sam. Often, the art had to be tucked into secrecy, or masked as something else in order to reach an audience. But there will always be kids who are ready to learn about their country’s underbelly. I’ll confess that it took me a while to come around to my spouse’s point of view, but re-reading Uncle Sam was what sealed the deal for me. Its climax is a battle between the Sam we’ve followed and the Bad Sam, the one who is animated by greed, cynicism, and evil. They have a war of words, and briefly of fists. But the conclusion is unspeakably beautiful: as the Bad Sam screams out Reagan’s catchphrase, “It’s morning in America!” our Sam heaves in a breath. Without a zingy one-liner, he simply exhales in Bad Sam’s direction. The symbol of all that I can’t stand about my country simply blows away into a cloud of nothingness. It had been a myth, but ultimately an empty one. Sam wakes up on a street corner, baffled but newly hopeful. A couple walks by and asks after him, then gives him some money and wishes him well. The Good Sam is the Uncle Sam of the America that my spouse salutes, built and tended to by the despised, the discarded, the homeless. On an anniversary of an awful day, let us believe in that America, the one that cannot be crushed, no matter how hard the powers that be squeeze it. Let us have faith that it will rise again, and higher and better than before. Let us believe.

ELSEWHERE IN FLAMING HYDRAAt How Things Work, Hydra Hamilton Nolan has a clear-sighted, compelling analysis of Dick Cheney’s endorsement of Kamala Harris.

|