The Compaq Deskpro 386 permanently changed the computer market, though not too many at the time realized just how substantially. The first major change was that innovation was occurring outside of IBM within what was formerly the IBM-compatible market. That is, the market that IBM had created was now moving away from IBM itself. The second major change was with the operating systems people used. The Compaq Deskpro 386 was the first machine to ship with Windows/386 and was capable of running MS-DOS applications in a VDM. Compaq was decidedly ahead of IBM in both hardware and software capability, and the market was responding. On the 2nd of April in 1987, IBM announced the Personal System/2 series of computers. These were the PS/2 Model 30 (an 8086 desktop, 8530), the Model 50 (an 80286 desktop, 8550), the Model 60 (an 80286 tower, 8560), and Model 80 (an 80386 tower, 8580). The entry level model 50 was essentially a modestly improved PC AT. It used an Intel 80286 clocked at 10MHz and 1MB of RAM (expandable to 7MB). The machine had a serial port, a parallel port, integrated video, one three and a half inch floppy disk drive that could read disks of 720K and 1.44MB, one 20MB hard disk, and it had three expansion slots. The computer had a smaller foot print than the AT, and it cost $3595. The biggest changes with the Model 50 were in video, expansion, and keyboard connectors. For video, the PS/2 Model 50’s video graphics array was integrated on the motherboard, a first for IBM. Additionally, this single video controller could output monochrome, CGA, EGA, or VGA. As regards those expansion slots, they were a completely new type of slot, Micro Channel Architecture (MCA), and they were incompatible with all previous expansion cards. Then, the keyboard and mouse ports were six pin mini-DIN. These ports are still around today on some PCs, and they are effectively just miniaturized AT keyboard interfaces. The Model 50 was the most popular computer from IBM through 1989. The Model 60 was equivalent to the Model 50 in almost every way. The primary difference is that the Model 60 was physically much larger, shipped with larger capacity hard disks (44MB or 70MB), and had four more expansion slots. Pricing for the Model 60 started at $5295. The Model 60 was the poorest selling of all PS/2 models. Both the 50 and 60 received faster RAM and greater capacity RAM with an update in June. These newer iterations were the 50 Z and the 60 Z. The Model 30 became a 286 machine in September, but it continued to use the ISA bus. This latter version of the Model 30 did decently well. These models went on sale later in April and shipped with PC-DOS 3.3 as IBM’s OS/2 wasn’t yet available. The IBM 8580 made its way to the market in July. The most powerful of all of the first PS/2 machines, it was outwardly similar to the Model 60. Inside it was quite different; it sported an Intel 80386 clocked at 16MHz, up to 16MB of RAM, three 32 bit MCA expansion slots, four 16 bit MCA expansion slots, and one 16 bit MCA expansion slot intended for use specifically with video adapters. For disk drives, the buyer could select a 44MB ST-506 drive, ESDI drives of 70MB, 115MB, or 314MB, or SCSI of 120MB or 320MB. From the announcement for the machine:

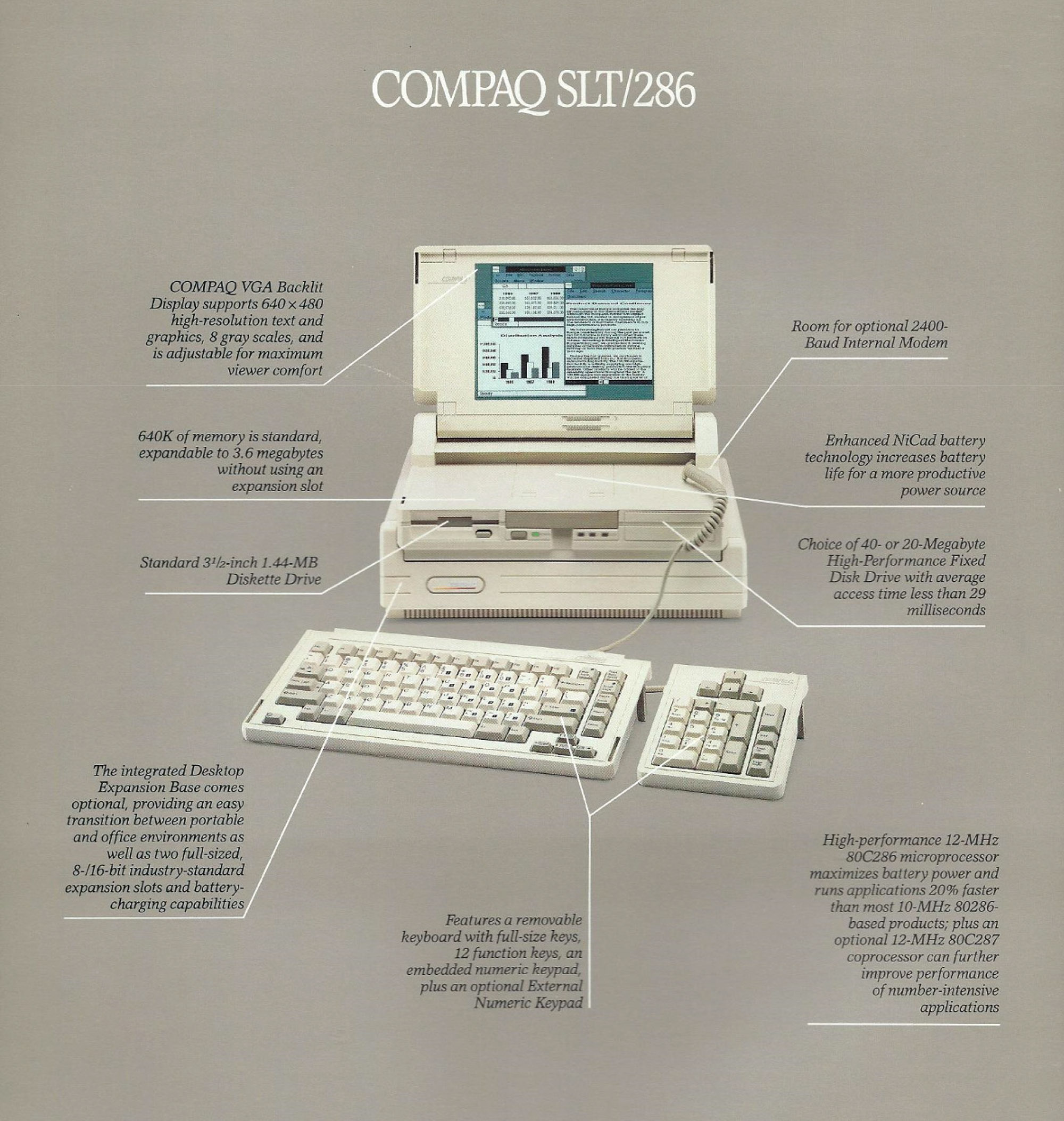

The first version of OS/2 to ship was originally intended for the 80286, and it was a text mode system. When OS/2 finally became 32 bit with version 2.0 in 1992, most users of the PS/2 line were already running Windows 3 which had been released in 1990. For those who’d purchased the Model 80, there were also ports of XENIX and AIX available. Despite the PS/2 line actually having moved quite a few units (around three million in two years), the computer market had expanded so dramatically that this sales figure was considered a failure. Worse, clone makers chose not to license MCA. Unlike IBM, Compaq had 286 and 386 machines available that sported five and a quarter inch floppy disk drives so that users could install their old hardware, ISA slots so that users could install their old expansion cards, and Compaq’s machines were generally more affordable than the IBM equivalent. When news of the PS/2 line first made its way to Compaq, however, the market reaction was completely unknown. Inside Compaq, the company’s leadership had met and they’d determined their position. Compaq publicly announced that they had no intention of licensing the MCA bus technology unless and until the public demanded it. They further publicly committed to making hardware and software that was fully compatible with already established industry standards. In a clever move, Canion compared the PS/2 to New Coke, but not everyone agreed. Many people were continuing to place their bets on IBM. Compaq announced the Deskpro 386/20 on the 29th of September in 1987. This new version of the Deskpro bumped the CPU to 20MHz, had a cache controller that allowed peripherals and the CPU to access memory simultaneously, and it featured a 32 bit math coprocessor from Weitek. With these changes, the Deskpro 386 was indisputably faster than the Model 80. Just to rub it in, Compaq brought the same advancements to the Compaq Portable 386. According to Kleiner Perkins, Compaq closed 1987 with over $1 billion in sales revenue making it the fastest company to have done so up to that time. There was one issue that Compaq faced. The company had very loudly and very publicly declared that it wouldn’t sacrifice backwards compatibility. The company had also stated that IBM was fumbling with MCA on the PS/2. Still, IBM had a 32 bit bus for their 32 bit computer while Compaq did not. Compaq didn’t want to do anything proprietary. The entire business was built on there existing a broad market of compatible machines, and this was something that the company intended to protect. Compaq’s solution, therefore, was to design and develop the bus, the controller chips, and the slot and then give it away. They planned to bring together Intel, Microsoft, expansion board makers, and other PC makers to get broad agreement. By January of 1988, Compaq had a list of companies whom they intended to recruit. The first meeting that they made was with Bill Gates over at Microsoft. He enthusiastically supported the idea, and he even got Compaq in touch with the correct people at each company on the list. The next meeting was with Intel where Compaq already had a good relationship. They were in, and they liked that they’d be the company making the chips required. As promised, BillG had called HP and warmed them up to the pitch that Compaq was to present. After the initial meeting, the two companies’ engineers were in correspondence working out details, and after a few weeks, Robert Pruette called Canion and expressed their intention to join the coalition. Following HP, Compaq managed to bring AST, Epson, NEC, Olivetti, Tandy, Wyse, and Zenith into the Gang of Nine. This new bus was called the Extended Industry Standard Architecture (EISA), and it had nothing to do with Big Blue. In the late morning of the 13th of September in 1988, executives from the Gang of Nine were gathered at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in NYC for a press conference. The first of the executives to speak was Rod Canion. For the most part, he jumped right in on EISA. While he didn’t say, “Compaq gave you compatibility,” he took some time to explain the necessity of compatibility as that was the context for EISA vs MCA. He then mentioned that about two thirds of all computers sold were based around the industry standard architecture, that MCA was about twenty percent, and that Apple made up the remaining thirteen percent. Finishing his remarks with some hopeful rhetoric, he was met with tepid applause. Albert Yu, VP of Intel, then took the stage, followed by Steve Ballmer of Microsoft. As the host, Richard Shaffer, returns to the stage and opens things up for questions, he announced that add-in card company executives were also present. The questions came, and when a pause was found, Shaffer closed out the formal event stating that all members of the panel would be available for interviews. It wasn’t altogether a wonderful response, but everyone involved was more or less prepared for that as such was the power of IBM in the minds of people at the time. The next day, the Wall Street Journal ran a full page ad purchased by the Gang of Nine whose text in large, bold letters said “Over the past eight years, business has invested more then $100,000,000,000 in industry standard personal computing. Today it just paid off.” No one need have worried. Following the event and the ad, that New Coke comparison became a bit more common, and the corporate press was taking notice of IBM’s market share losses since the introduction of the PS/2. On the 19th of September, Compaq expanded their product line to include five 80386-based machines at five different price points. In October, Compaq brought the SLT/286 to the market. This was a fourteen pound, battery powered, 80286-based, LCD packing, hard disk spinning beast of a machine. I wouldn’t quite call it a laptop given its size, weight, and detachable keyboard, but it was close to that form factor. Compaq wasn’t the dominant player in the industry. Compaq was number three. IBM was the market leader, Apple was the second largest, and Compaq was third. The important thing, however, is that Compaq was the largest of the IBM-compatible computer companies, they were growing, and they apparently lacked fear. It’s also worth noting that the 8 bit and 16 bit ISA busses we all know and love had been referred to as the PC bus and the AT bus, but around this time, they began being referred to as the ISA bus. The coup within human minds had already been won. EISA was the extension of an existing standard while MCA was the aberration. Compaq closed the year with over $2 billion in sales. Building upon the SLT, Compaq introduced the LTE line on the 15th of October in 1989. These machines were true laptops or notebooks in the sense we think of them today. The LTE/286 measured eight by eleven inches, was just under two inches thick, and weighed in at just under seven pounds. To achieve this, Compaq had adopted surface mount technology for nearly everything which allowed them to shrink board sizes. This size reduction extended to HDDs and floppy drives as well which allowed the LTE/286 to maintain large storage capacities, off-the-shelf software installation, and a full-speed 80286 CPU. The LTE/286 could also be fit with an 80287 for those needing it. Compared to other laptops of the time, this was a remarkable achievement. The Toshiba T1000SE released around the same time was lighter, but used a battery-backed RAM card limiting the machine 2MB of storage. Meanwhile, the LTE/286 could be fitted with a 40MB hard disk. The only true annoyance of the LTE was its display: 640x200 super twist LCD. While both a poor resolution and not a great visual experience, the technology did allow Compaq to produce a display that was both thin and light… even if I’d rather use the orange gas plasma displays of their luggable machines. Of course, I said this was the LTE line, not just the LTE 286. There was an LTE with an 80C86 clocked at 9.5MHz, 640K RAM, three and half inch 1.44MB floppy disk drive for $2399. The base model also lacked a socket for a math copro. For the 286-based machines, there were three models. The base model of the 286 was roughly the same as 80C86 version except for upgraded CPU. The Model 20 came with a 20MB hard disk, and the Model 40 featured a 40MB hard disk. The 8086 had a max RAM capacity of 1MB while with 286 had a max RAM capacity of 2.6MB. All of the machines featured an expansion slot on the right side which could be outfitted with a 2400 baud modem. Other external connectors were serial, parallel, video, and floppy disk. For all of this, the battery life of the machine was around four hours for the 286, around five hours for the 8086, and certain power saving features could be managed with the The Compaq SystemPro was shown to the world for the first time on the 6th of November in 1989. This was a beast of a machine. This was a floor-standing machine that could accommodate up to two 80486 CPUs clocked at 33MHz, up to 256MB of RAM, and up to 1.6GB of disk storage This machine used the EISA bus, and it also used an early RAID system. Pricing for the SystemPro started at $15,999 for a single 80386 CPU, 64K cache, 4MB of RAM, and 240MB of disk storage. At launch, SCO Unix was the only operating system capable of making full use of the hardware, but both OS/2 and Novell NetWare gained support for the machine over time. The most fascinating OS choice was Windows NT 3.1 which had some code specifically for the SystemPro. But given how much later NT shipped, I imagine that most SystemPros were running SCO Unix. For those who purchased a SystemPro, the machine would offer serious upgrade potential over time with eight internal hard drive bays, slots for Weitek copros, compatibility with the 80486, and seven EISA slots. A single SystemPro was capable as serving as a host to sixty UNIX terminals. Given that target, the SystemPro was roughly six times faster than a DEC VAX6310 but cost more than $100000 less. This is a particularly apt comparison as the VAX6310 launched in January of 1989, supported a maximum of 256MB of RAM, and could be fitted with multiple CPU modules. Compaq, Intel, Microsoft, and SCO were now not just aiming at IBM but also at all of the minicomputer makers. Simultaneous to the debut of the SystemPro, Compaq released an updated Deskpro that made use of EISA and could accommodate an 80486. Unfortunately, the years 1990 and 1991 weren’t kind to Compaq. While the company had saved the compatible market, fired the first shots against minicomputers and mainframes with high-end microcomputers, and largely set a standard of excellence within the clone market, Dell, AST, and Gateway were rapidly eating away the company’s market share. Their machines were just far less expensive. This was especially true as the US dollar strengthened globally and more than half of Compaq’s sales were outside of the USA. The company had gone from third to fifth. There were also a number of mergers and acquisitions within the dealer network which hurt Compaq’s bargaining position. Compaq experienced its first quarterly loss since 1983 (roughly $70 million), laid off fourteen hundred employees, and the company’s stock price fell by more than two thirds. Rod Canion left the company on the 25th of October in 1991 followed shortly thereafter by Mike Swavely (President of Compaq North America), B. Kevin Ellington (VP of Market Development), C. Murray Francois (VP of QA), Robert E. Vieau (VP of Manufacturing), and Jim Harris (SVP of Engineering). Eckhard Pfeiffer then became CEO having previously served as the head of foreign operations. Following Canion’s dismissal by Ben Rosen (chairman), over a hundred employees gathered outside the company’s headquarters to protest Canion’s departure carrying signs expressing their love and admiration for their leader. Weeks later, the selfsame group of employees bought an ad in a local newspaper that read "Rod, you are the wind beneath our wings. We love you." With Pfeiffer at the helm, Compaq’s new mission was to compete in the budget-friendly PC market to which Compaq had been losing so badly. This started with the Compaq Presario launched in 1993. Initially, these were all-in-one machines with a fourteen inch monitor, Intel 80486 clocked at 25MHz, a 200MB hard disk, and Windows 3.1. Pricing started at $1400, and these machines typically included America Online along with other bundled software. Compaq’s return was swift. The company became the first major name to to use CPUs from AMD and Cyrix to hit their desired price targets, and was therefore one of the first major brands to offer a PC for less than $1000. To keep driving prices down, Compaq went into a joint venture with ADI, a Taiwanese manufacturer of computer monitors who’d made a good number for Compaq. Compaq and ADI setup some factories in Mexico and Brazil where the monitors were manufactured and stored. Further completing the product offerings Compaq had, the company began working with Cisco in June of 1995 to get into the network business having failed in a bid to acquire Applied Network Technologies. Compaq wasn’t the same company, but it was firing on all cylinders and their dominance in the market seemed to be certain. I have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment. You're currently a free subscriber to Abort Retry Fail. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |