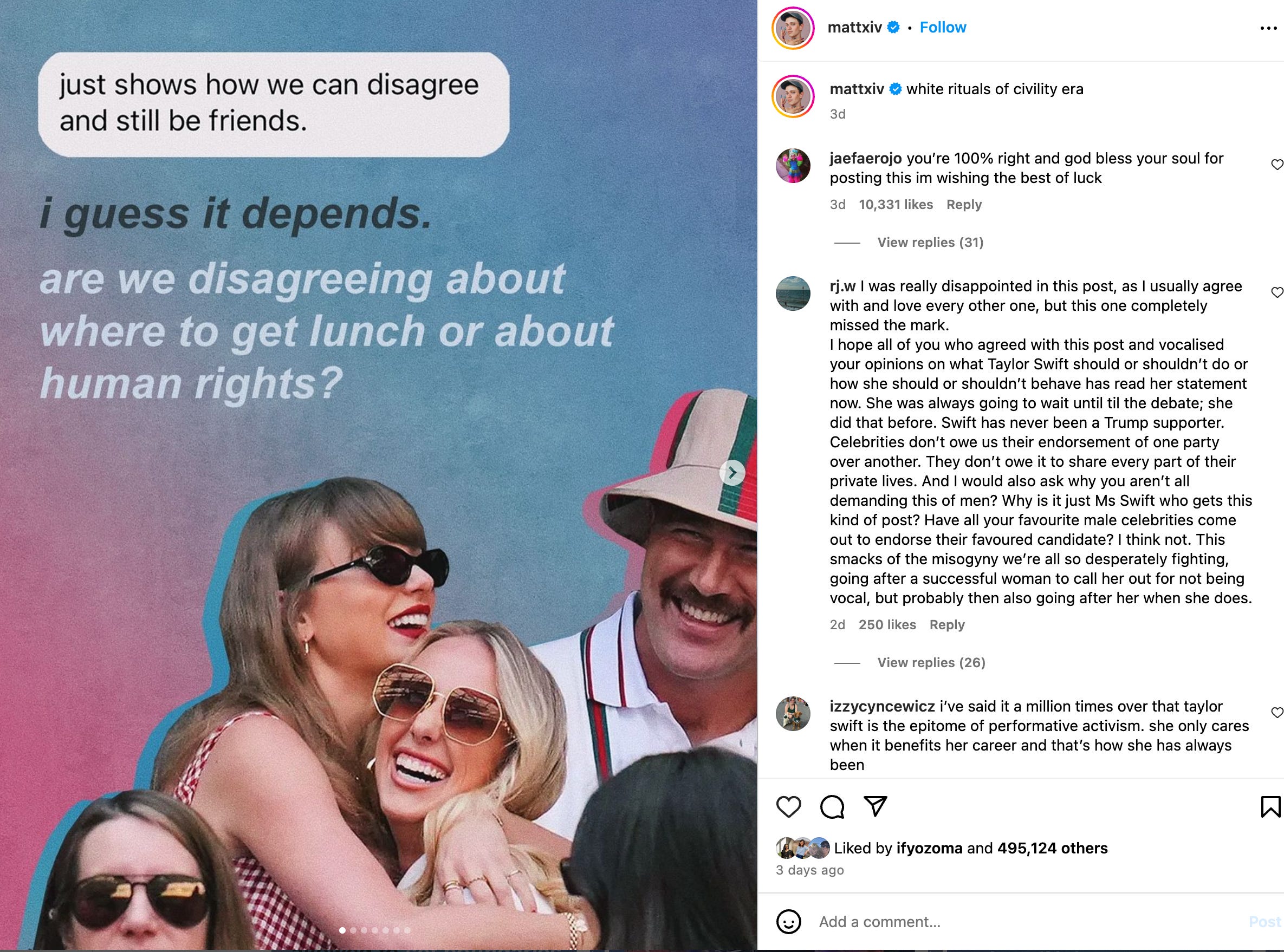

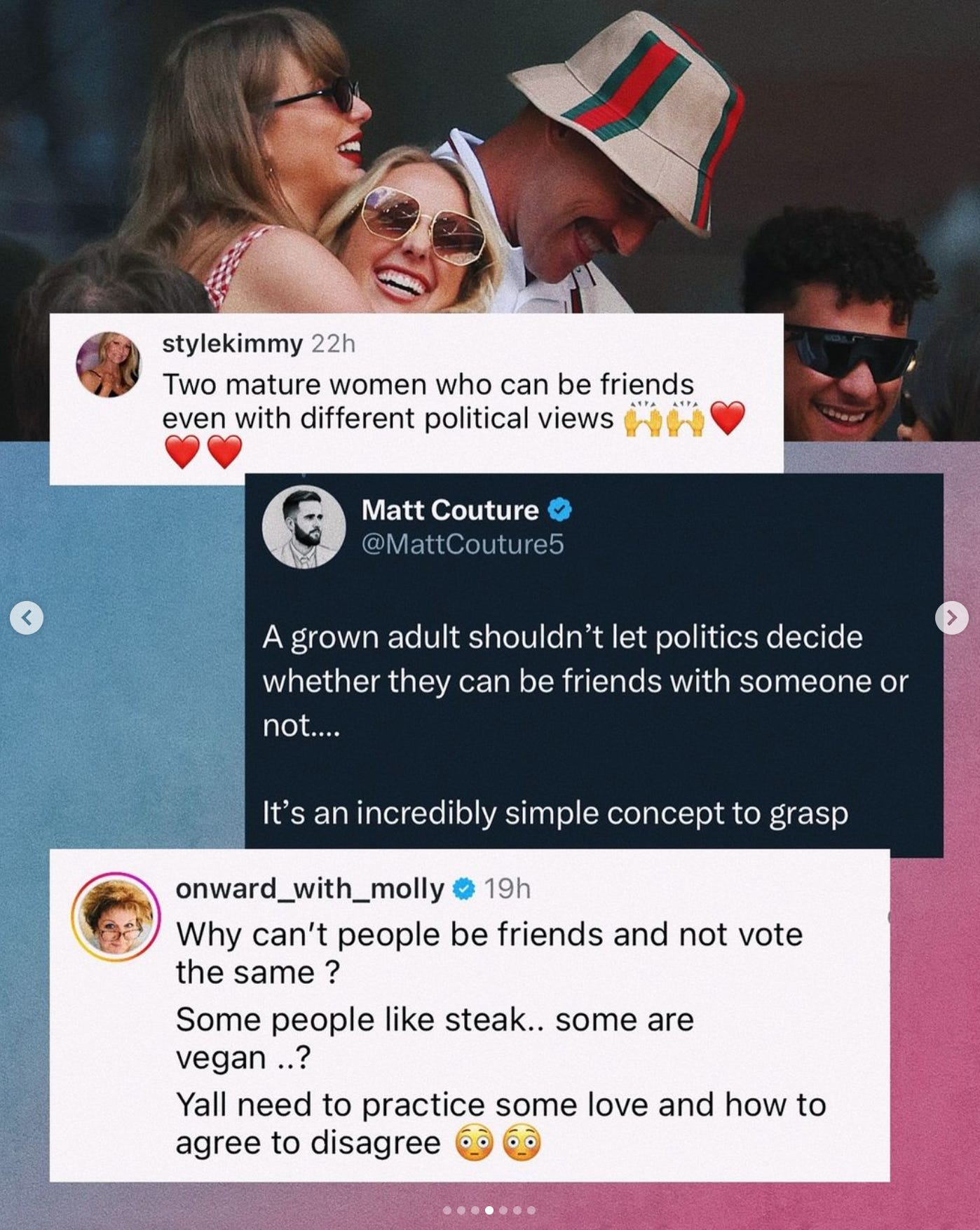

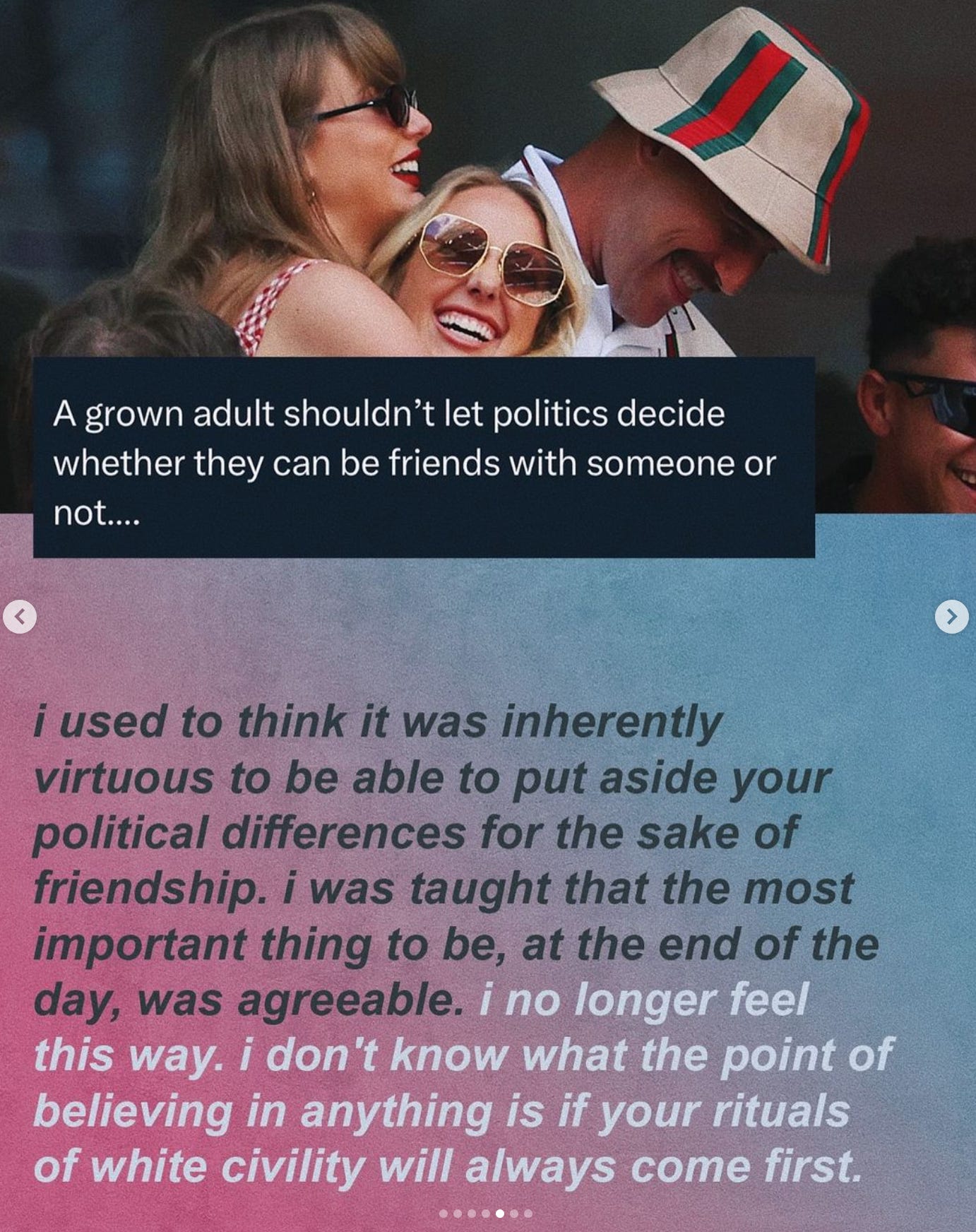

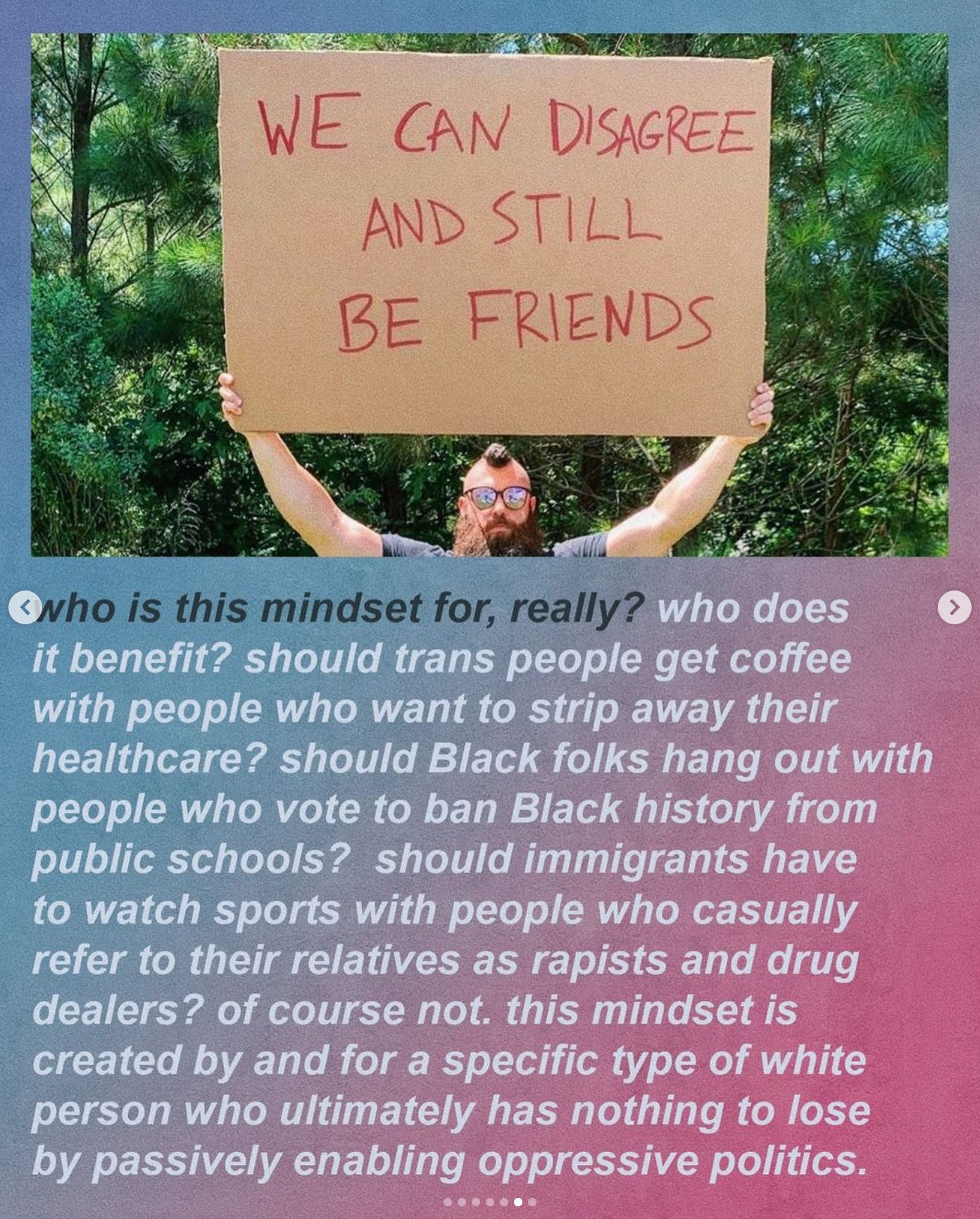

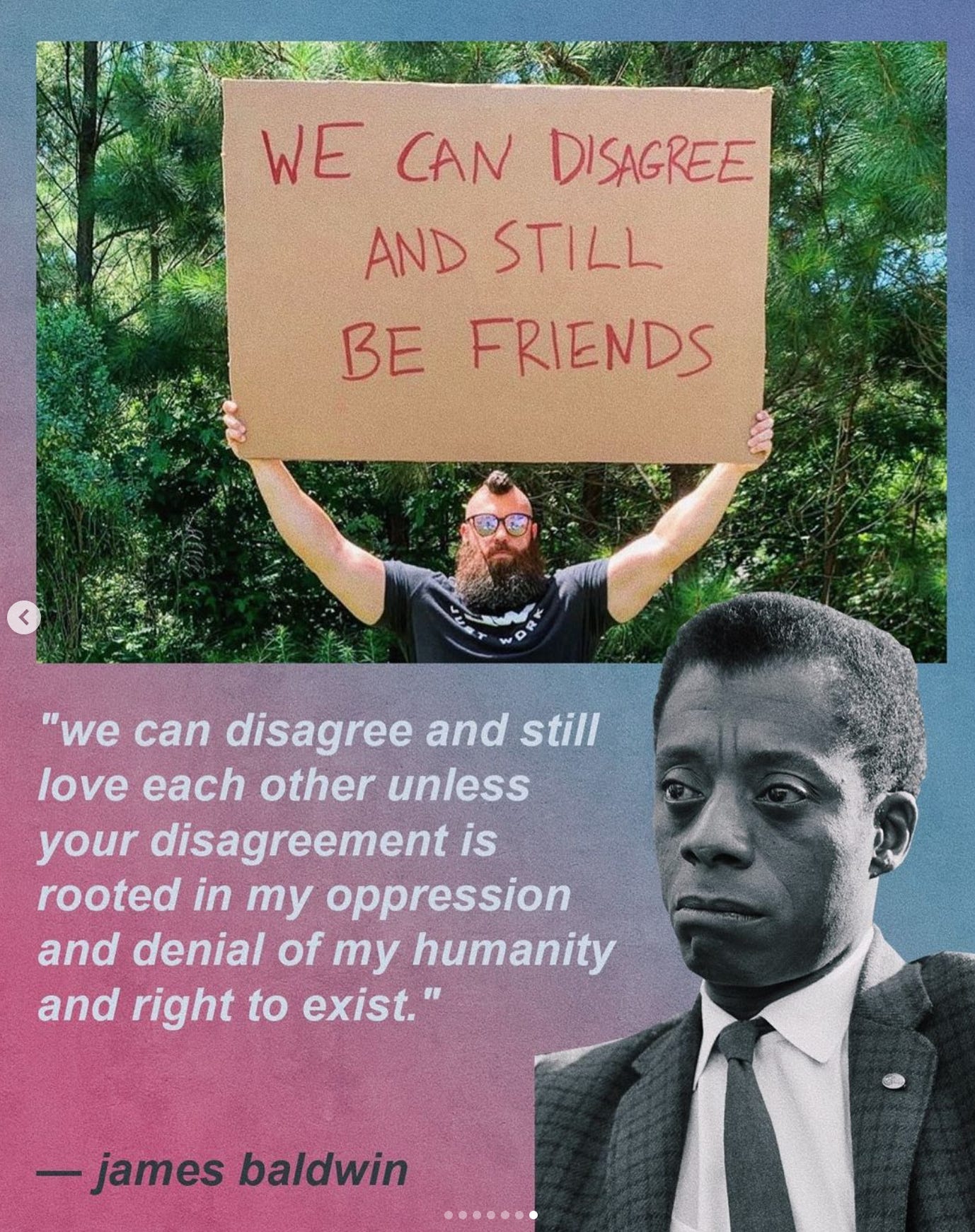

White Celebrity and Rituals of CivilityTaylor Swift, Brittany Mahomes, Kate Middleton, and Culture StudyYour subscriptions keep the paywall off posts like this one — which makes it possible for you to share it with others. Your subscription also gets you access to this week’s expansive threads — and forthcoming threads that will pack your TBR list and give you the opportunity to seek advice on anything and everything from a bunch of wise internet strangers. If you have the means and you’re not already a subscriber, consider joining us. Earlier this week, Matt Bernstein — better known as mattxiv, podcaster and tremendously successful meme/slideshow creator — posted a series of slides to his Instagram with the caption “white rituals of civility era.” The reference was Taylor Swift’s friendship with Brittany Mahomes, forged in the early days of Swift’s relationship to Travis Kelce. (Kelce and Brittany Mahomes’ husband, Patrick, are teammates/best football friends/etc. etc.) Brittany had recently “outed” herself as a Trump supporter by liking (and then quickly unliking) one of Trump’s Instagram posts, specifically (and this is important) one that outlined his policy plans for a second term: “Seal the border, and stop the migrant invasion,” “Keep men OUT of women’s sports,” “Carry out the largest deportation operation in American history,” and cut “federal funding for any school pushing Critical Race Theory, Radical Gender Ideology, and other inappropriate racial, sexual, or political content on our children.” Now, I follow a lot of people on Instagram whose beliefs I find abhorrent; if I liked and unliked a post from “The Transformed Wife” (a horribly bigoted trad wife) I could (rightfully) defend it as a slip of the thumb. But Mahomes doubled down. First, she posted a note to her stories: I mean honestly, to be a hater as an adult, you have to have some deep rooted issues you refuse to heal from childhood. There’s no reason your brain is fully developed and you hate to see others doing well. The next day, she posted a screenshot of a tweet, adding “READ THAT AGAIN!” I don’t want to get too bogged down in the timeline that followed, but the basics are straightforward. Trump was thrilled and posted about it; fans began speculating how and whether Swift would distance herself from Mahomes; Swift appeared at the most recent Chiefs game in a different VIP box than Mahomes; Hunter Harris pointed out that Swift’s mastermind publicist Tree Paine was likely losing her shit….and then, on September 8th, Swift gave Mahomes a big hug at the U.S. Open (with Travis Kelce grinning in the background). That image is what you see in the mattxiv slide at the beginning of this piece — and the slides that follow point to a fundamental tension at the heart of white liberalism: I first started seeing this discourse about civility and friendship pop up after the 2016 election, which transformed more abstract “political differences,” particularly on the part of the white men and women who effectively voted Trump into office, into palpable political danger. There was a camp of people who said: if your friend or family member supports Trump, you have to end that friendship or distance yourself from that family member. I saw this argument arrive most forcefully from white liberals addressing other white liberals, who are statistically more likely to have friends or family members who voted for Trump. Like a lot of things in those post-2016 years, the message often felt absolutist in a way that only those who lived and grew up in exclusively liberal spaces could accomplish. But I understood, and still understand, the sentiment at the heart of the argument: white people with societal power cannot be allies to those with less of it if they’re also allies with those who believe in the eradication, degradation, and/or dehumanization of that first group of people. But over the last eight years — and, most vividly, over the last two — I’ve watched another discourse emerge from the moderate (and usually older) wing of the Democratic party. It was forcefully on display in Tim Walz’s convention speech, where he talked at length about his relationships with people who voted for Trump — in part because many of them also voted for him. (And even if they didn’t, he’s still civil with them). This sentiment is particularly persuasive amongst older voters whose relationships (with friends, but also with family) were forged in a time of far less political polarization, and when the difference, particularly on the local level, between Democratic and Republican candidates was far less extreme. Crucially, those relationships might also date before the most recent political realignment, when identity became the primary indication of political persuasion. Today, if you know where a person lives, how much college they’ve attended, how much money they make, their religious beliefs, their gender, and their race, you can predict (with great certainty) their political party. But in the 1970s or ‘80s, if you were a white person who lived in a rural place, worked at a factory, and went to church, you could’ve just as likely been a Republican as a Democrat. A small town — or even a largely rural and religious state, like Idaho — could swing back and forth between the control of both parties. My Presbyterian church was filled with Republicans and Democrats when I was growing up; of course I knew them. Now, I bet you could count the Democrats in the pews at that church on one hand. So you can see how this argument operates: I know this person; I know their family; I know their kindness. Just because they vote for Trump doesn’t make them a bad person. And if you’re a white person, a citizen, able-bodied, and cis-gendered, it’s true: that person has likely always been a kind person to you. I’m sure Brittany Mahomes has never been anything but nice to Taylor Swift. What that argument misses is how societal power insulates both members of this theoretical friendship from the consequences of Trump’s politics. The stakes, in other words, are very low. Why blow up a friendship, cause a riff, make a scene over something that doesn’t personally affect you? But instead of acknowledging that insulation, you come up with a narrative that valorizes civility. This is what Bernstein invokes so well in the slideshow: the mindset that “is created by and for a specific type of white person who ultimately has nothing to lose by passively enabling oppressive politics.” That last adjective is key: these aren’t just politics. They’re oppressive politics. The post that Brittany Mahomes liked wasn’t, I dunno, some state legislator advocating for cutting taxes on the rich. It was a post outlining Trump’s oppressive policy stances. You can only be truly friendly with oppression if it’s not oppressing you. But here’s where we get to the complicated part — the part where I have Garrett Bucks’s writing clanking around in my head, reminding me that separating my “good” white self from those “bad” whites is just a different easy way out. It’s a narrative that also, in some ways, fetishizes civility: you’re avoiding the sort of conflict that could occur if you used the trust and intimacy at the heart of your connection as the beginning of a much more difficult conversation. And I’m not talking about getting in fights on Facebook with someone you haven’t seen in person since 1998, I’m talking about setting out the stakes of oppression, in person, with someone you love. Awkward! Bad! So much potential to come off as self-righteous and preachy! But we know people don’t change their political minds because of ads or speeches. They change them — often very gradually — through conversations. Or very targeted slideshows for your Midwestern Dad, like the one in the TikTok above. Is Taylor Swift having these conversations with Brittany Mahomes? I dunno! Should she? If they’re actually friends, I think so. In fact, the way someone reacts to your attempt to humanize other people who matter to you might clarify whether you actually want to remain friends with them. ● I don’t think Swift and Mahomes need to have a public debate or anything that ham-fisted. But I do think she pulled a pretty classic white lady move, which was to respond to criticism of her associations with a narrative-changing declaration of individual belief. From a PR perspective, this is masterful. The timing, the cat, the AI bit, the reference to her own research and specific policies that matter to her, the link to register, all of it. Some argued that this declaration jeopardizes her career, but some people are delusional. Fans already knew her politics. This changes nothing in that regard. Getting people registered to vote is powerful; so is activating (even more) fan energy around the Harris campaign (even before the announcement, Swifties for Change had raised more than $163,000 for Harris). Swift is already balancing so many contradictory demands to do with her relationship, her appearance, her fashion, her music, how she should or shouldn’t react to Katy Perry dropping the c-bomb at the VMAs — classic Good Girl Trap stuff. If she released a statement about how she and Brittany talk about politics, chances are very high it would come off as both corny and cringe. So that’s not what I want. I don’t think it’s what anyone wants. I don’t look to celebrities as models for action, but as opportunities for reflection on how power operates — in society, but also in my life, in my writing, and in the stories I tell myself about which conversations are worth having and avoiding. Interestingly, the “rituals of white civility” discourse popped up earlier this week, when part of the conversation about Kate Middleton and her post-chemo cancer video considered whether or not it was nice, or appropriate, to analyze the publicity video a royal figure releases in the wake of a serious illness. There’s a line between “meanness” and analysis that’s often hard to parse with celebrities — and I think it’s particularly hard to parse for those of us who have watched various celebrities, many of them our age, destroyed by the demands of fame. If you’ve never taken a media studies class (or been asked to read and perform engaged analysis of a media studies object) it’s even more difficult. If you don’t have anything nice to write, don’t write anything at all. I’ve seen this sentiment manifest in various ways since I first started analyzing celebrity on the internet: on small blogs, on BuzzFeed, in the New York Times, and here in the newsletter, regardless of form or length or academic tone. And it always comes out strongest when I’m writing about white women. There’s the classic retort that you’re just jealous, but there’s also the ringing accusation that I’m tearing other women down. I understand this reaction. For some, it’s a very tender way of trying to protect a figure who, for whatever reason, seems vulnerable. Many of us have been socialized to understand talking about other women as gossip, and gossip as one of the primary ways women police each other (and maintain our own subjugation). But that understanding elides just how much power these particular women wield, how much work their images do in propping up larger ideologies, and how deftly that work manages to avoid scrutiny. It is profoundly un-intersectional, in other words, to think of Kate Middleton uniquely as a woman, and not a white unspeakably rich mother who wields tremendous power. That power might be “soft,” but it’s still power: power that reproduces itself, despite profound anachronism, through obstruction. You make the queen-to-be relatable, you make analysis feel objectionable, and you effectively insulate the monarchy from critique. In this framework, it’s fine to say that colonialism is bad, but it’s déclassé — at least as I’ve seen it manifest in the U.S. — to criticize the person who’s its most likable figurehead. It’s also worth spelling out that these celebrities are not suffering because of these critiques — or even reading them. I mean, I wish they would! That would be cool, maybe a little moment for self-reflection! But they’re not. I’m not injuring them, and I’m not writing for them. I’m writing for me, and I’m writing for you. Because celebrities are ultimately ciphers that enable us to talk about the things that matter in our lives — including how we can and should relate to those who endorse oppressive politics. They’re the glossy hook that makes talking about various ideologies (in this case, “white civility”) compelling. But their status as humans also periodically complicates the conversation. I think there’s also some understandable projection going on in cases like this, whether it’s Middleton or Swift or any other relatable white celebrity. I have certainly been that white lady who’s muttered to myself I just can’t win when I fail to meet the exacting but not always unfair standards of the internet. What do you want her to do!! is really What do you want *me* to do!?! But one thing I’ve learned when it comes to criticism is to sort the irrational (usually unrooted in anything I’ve actually written) from the considered, and then let that criticism hang out in my mind for a while as I figure out how and whether I could do things differently. What perspective did I miss or not fully consider, what framing did I neglect, what questions was I not asking myself (or you, as readers)? ● Back in 2017, I wrote a feature for BuzzFeed News about “Ten Long Years of Trying to Make Armie Hammer Happen.” I’ve previously written about the dog death threats and general vitriol directed my way in the wake of that piece, much of it fanned by Hammer himself — and how it it made me doubt my skill, my framing, and whether I should continue to analyze celebrity images at all. I never said this out loud to anyone, but I basically decided that if I was going to write about a celebrity, I'd only analyze the images of stars I found interesting and in some way praise-worthy — see, for instance, this analysis of Charlize Theron. I was already dealing with so much political vitriol. Why subject myself to celebrity-related hate as well? My Hammer thesis was later borne out, but I’d already internalized the lessons of the initial blowback. And a lot of writers who came up in digital publishing at that time were internalizing similar ones. Back in the gossip blogging days, it was a lot easier for someone like Perez Hilton to just spout horrible shit about celebrities and use Microsoft Paint to draw penises on paparazzi photos they’d stolen off the internet. Fifteen years later, the easy way was to write about how awesome a celebrity was. Fandom, but make it journalistic. To be clear, that style of press had been around for decades — it’s the guiding ethos of the fan magazine industry and the so-called “personality journalism” we associate with People and Entertainment Tonight. I also know that in the 2010s, my former employer was partially responsible for the shift back towards “nice” - a posture that was aall ways strategic. “Sharing” on social media was the beating heart of BuzzFeed’s success, and people (particularly women, who did the vast majority of social sharing) were far more likely to share when the story was positive. You might assume that my editors pushed me towards positive frames, but at least in my corner of the company, that was never the case. In fact, I’m sure one of my editors would’ve loved it if my stories had been more sharp, more comfortable with the pillory of a particularly noxious celebrity. But like the rest of my colleagues, I also knew that whatever I wrote, I would be the primary recipient of the backlash. If someone pressed the “tweet this” button on an article, the tweet that auto-populated would automatically include my handle. The feature was intended to build a writer’s social media following (which it did) but it also put the writer immediately and directly in the line of fire. Same with any retweet by the main BuzzFeed account and its millions of followers. So after the Hammer maelstrom, I watched myself become more celebratory and less critical — or at least less critical of anyone I knew people actually liked. You might think that leaving BuzzFeed — and, after Elon, Twitter — to write an independent newsletter would liberate me to write about celebrity however I wanted. But like anyone else who’s paid directly by their audience, I can be a coward. Will this make people unsolicited ? Will this? How about this? When Sara and I were chatting about whether or not we should write about the Middleton video, we both knew that we would probably piss some people off. And we did. Some of the conversations I really appreciated, particularly the ones about approaching this video through the lens of a person who isn’t and hasn’t been chronically ill. Several of you made points that I have internalized as I think through how I’d do a piece like this differently in the future. But the one that stuck in my craw was straight-up policing. This isn’t Culture Study. It’s the sort of comment that’s meant to injure. It touches on that vulnerable part of me that wants, above all, to be liked — because likability is the primary source of my own power as a white woman. It’s also meant to steer me away from celebrity analysis, and to keep me focused on topics that don’t touch visible nerves — or, more precisely, that only interrogate power and oppression when it’s bold-faced, and when naming it doesn’t require interrogating our own participation in its larger project. There are so many places on the internet you can go to find that posture. But that — that’s not Culture Study. When I hang out with other newsletter writers, we often talk about how our best readers are the ones who know that a good writer, a trustable writer, is someone who won’t always write exactly what they find interesting - and whose beliefs and interests might not perfectly match their own, but who consistently challenges them to think. Not think exactly the same, but think. Part of my success as a newsletter writer is rooted in the fact that I am white educated woman of a certain age who writes in a way that makes a lot of white educated women of a certain age feel seen. But part of that success is also a willingness to do the work even when it’s hard, or complicated, or discomforting — and to ask you to do it, too. ● For today’s discussion, I don’t think it’ll be useful or generative to rehash the Kate Middleton post-chemo video. Instead, I hope we can think about civility and niceness and how they relate to the protection of power, and how your thinking has evolved on the responsibility to try and change other people’s minds. There’s truly so many places we could go. And when I say “don’t be butts,” as I often do at the end of one of these posts, it’s not because I don’t think we should disagree — it’s that I don’t want to make this a place as hostile to conversation as the rest of the internet. That’s a needle we can collectively and carefully thread, and I’m grateful to be here trying to do it with all of you. And quickly, here’s This Week’s Things I Read and Loved: ... Subscribe to Culture Study to unlock the rest.Become a paying subscriber of Culture Study to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|