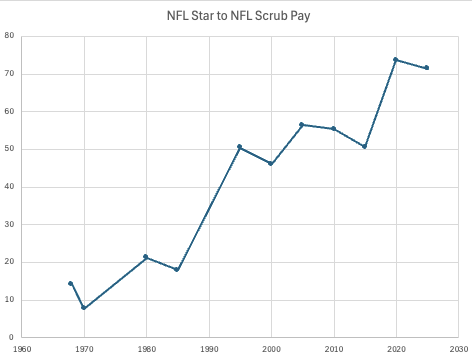

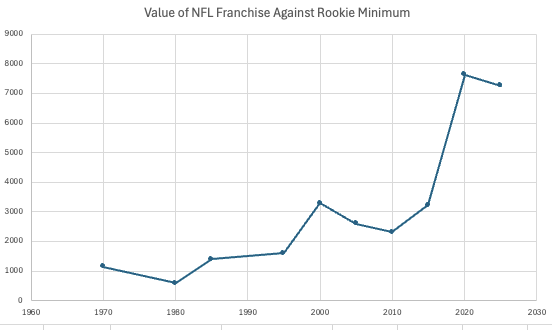

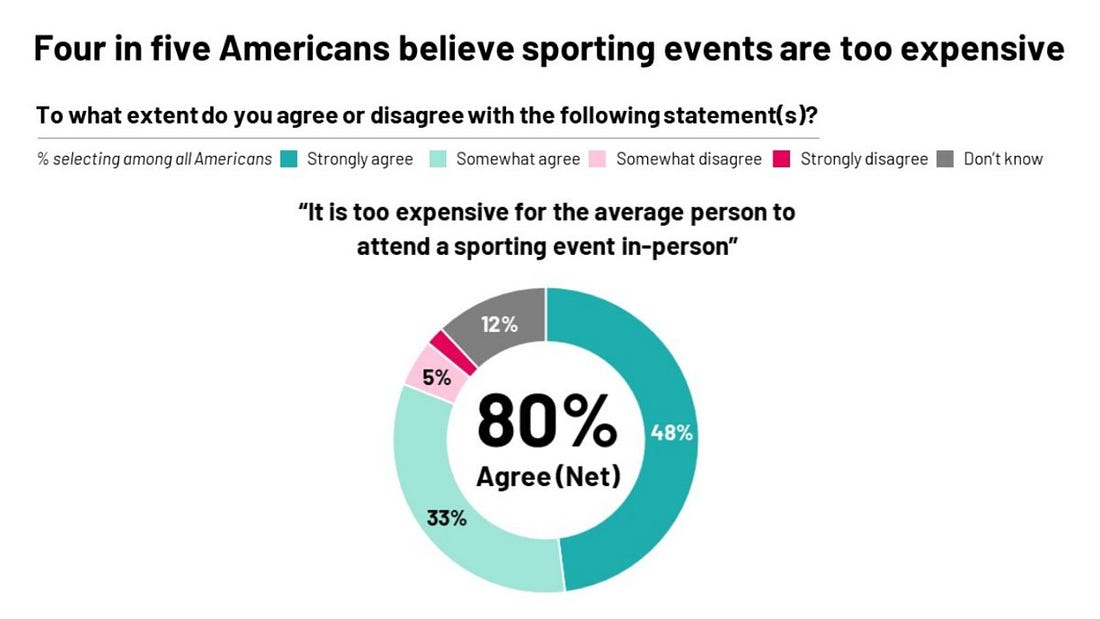

Monopoly Round-Up: American Sports in an OligarchyA billionaire owner NBA scandal hits the heart of the Democrats, plus fallout from the Google monopolization case, the end of the FTC campaign on noncompetes, and heat on Trump's antitrust corruption.Lots of news, as usual. The most important story of last week was obviously the Google remedy decision, but I already wrote that up. Instead, I will focus on a big story in sports, since it’s the kickoff of the NFL season. That said, there’s plenty to discuss on the Google front, including fallout and criticism of the decision, as well as the fact that there’s another break-up attempt of the search giant coming in just a few weeks. After the paywall, I’ll have the full round-up. What Does American Sports Look Like in an Oligarchy?I’ve been meaning to do a sports-themed piece for some time, what is motivating me now is a story that independent podcaster Pablo Torre published this week on corruption in the National Basketball League. In it, he linked alleged attempts to cheat at basketball by ex-Microsoft monopolist and L.A. Clippers owner Steve Ballmer, the sixth richest man in the world, aided by notable people in the Democratic Party. It’s a perfect illustration of how America works today. To get there, I want to start with how sports have changed over time, from when we were a middle class nation to our more oligarchy-style nation. Traditionally, from the 1920s onward, American sports were a sort of cultural public utility. On radio and then TV, depending on the sport, games were publicly available to a large local audience for free, financed by local advertisers. Going to the games was affordable, a fun thing to do, to grab a hot dog and beer and sit in the bleachers. “As American as baseball and apple pie" is just one of many expressions centered on this common experience. Stadiums and arenas were and still are often financed with taxpayer money, in part due to corruption, but in part because people are proud of their local sports teams and want them to succeed. (Pat Garofalo is the best writer on the topic of taxpayer-funded stadiums.) Even today, the biggest contests, like the World Series or Super Bowl, are national events. From movies like Major League and Friday Night Lights to video games like Madden, sports are a cultural currency that were recently available to everyone. First generation immigrants used sports to integrate into America, and NBA stars projected American soft power globally in the 1990s. To be clear, the business of sports was never based on equality. Teams were owned by rich locals, such as the Rooney family of Pennsylvania, which founded the Steelers in 1933 and still runs it today. And top players always did well. A great story is in 1930, when Babe Ruth was asked why he earned the fantastic sum of $80,000, which was more than the $75,000 salary of President Herbert Hoover, and responded, “I had a better year than he did." It’s a funny line, but it also speaks to a dramatic change in the U.S. In 1930, it was shocking to have an athlete make more than the President of the United States, today the President makes just $400,000 a year, which is less than half the NFL minimum for rookies. In other words, sports, like America, were unequal, but they were not that unequal, and there was a broad ability, with the obvious exceptions of race and gender, for the middle class to participate. The Legal Underpinnings of Professional SportsThe legal structure of American sports has always been a function of anti-monopoly and labor laws, because sports as a business is especially susceptible to monopolization. In most industries, competitors can operate independently, but sports leagues require collaboration by competitors. In addition, sports is really human effort and muscle, automating something or disrupting it with technology is besides the point. The business history of baseball, basketball, and football is thus littered with antitrust lawsuits, mergers, and strikes. One of my favorite stories about anti-monopoly law and sports is about the merger of the National Football League and the American Football League in 1966. This deal, which built today’s NFL, also created a clear monopoly of professional football in the United States, which was illegal, and would lead to suppression of player wages. So it needed special dispensation from Congress, but Judiciary Chair Emanuel Celler was opposed. Enter Louisiana Congressman and Democratic majority leader Hale Boggs, who had lost popularity because of his support for civil rights. Boggs attached such an exemption to a budget bill to route around Celler, on the condition that New Orleans would get a team and Boggs could become a local hero. In other words, today’s New Orleans Saints are a result of antitrust law. The story of the Saints is not an anomaly. The Muhammed Ali Boxing Reform Act, passed in 2001, broke the power of dominant bosses in boxing, meaning that top boxers gain most of the lucre from their matches. By contrast, the Ultimate Fighting Championship has monopoly power over its fighters, and has faced a series of antitrust suits forcing it to pay out large amounts of money to them. Major League Baseball has had a weird antitrust exemption granted by the Supreme Court in 1922, defended eventually by Robert Bork. The PGA Tour, by offering pro-am golf tournaments for members of Congress, killed off a Federal Trade Commission investigation in the 1990s There’s an alleged teenage cheerleading monopoly, Varsity Brands, which paid out tens of millions in settlements, youth sports from Little League to hockey is being taken over by private equity, and professional tennis players have filed antitrust claims against the major tournaments and tours. Donald Trump is trying to facilitate a monopoly between LIV Golf and the PGA Tour through a merger. NASCAR is under assault as a monopolist, by Michael Jordan of all people. And newer sports, like video game esports, are also seeing some antitrust/labor action. And antitrust is essential in sports. While labor unions matter, sports union are often less powerful than in other industries. Athletes have brief careers, and cannot exert much leverage by striking because the costs of a lost season are so high. Players are also focused entirely on training, leaving little time for business. In college sports, the athletes graduate in a few years, meaning organizing is almost impossible. And while there’s a lot of money involved, athletics are also a vanity project for billionaires. They are also political; most sports owners are very right-wing and tied to the GOP establishment, though some are pro-Wall Street Democrats. For instance, Ballmer is the sixth richest man in the world, but he’s also a basketball nut, so the Clippers, which are a small part of his net worth, are nonetheless his main focus. Even in the 1960s, owners had power, which is how they pushed the NFL and AFL merger through despite the opposition of Rep. Celler. In other words, owners have a ton of money and a lot of ego invested in tight control of a business venture whose main workers have little leverage. And they use this power, aggressively, even today. Sports in an OligarchyAs America has become more unequal, so have college and professional baseball, basketball, football, and even high school athletics. Even within sports, the inequality is much higher. Here, for instance, is a chart of the salary of the top NFL player against the rookie minimum. The top player in 1970, Jets quarterback Joe Namath, made a little less than ten times the rookie minimum. By 2025, Dallas QB Dak Prescott made over seventy times. And that’s not counting endorsements, salary guarantees, and all the other goodies that make it much easier for the top players. This compensation skew tears at the solidarity of the NFL Players Association, which has become quite weak over time. It’s even more extreme with the value of a team, which puts the owners and players on a completely different footing. In 1972, a rookie at a league minimum would have to play a thousand seasons to buy an NFL team. By 2025, that was over seven thousand. And most of that increase was during the 2010s. And of course, this inequality is hitting the consumer as well. Going to a professional game is now so expensive it’s impossible for middle class people to make it a routine part of their lives. Here’s sports reporter Joon Lee:

Nebraska Senate candidate Dan Osborn did a thread on the problem, chalking it up to billionaire owners. The Chaos of OligarchyAlong with this increasing inequality, there are three other reasons the sports landscape is in chaos. The first is that the main financing mechanism for both college and professional sports - broadcast TV - is moving to streaming. The second is that the advertising to support sports is oriented increasingly around gambling, which introduces a host of conflicts of interest. And the third is that college sports, which is the basis for training Americans for both professional sports and the U.S. Olympic teams, was upended by a Supreme Court antitrust decision saying that the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) can no longer engage in key restrictions of student-athlete compensation. This decision has spurred a reorganization in college sports and TV networks. Let’s start with streaming. Earlier this year, ESPN owner Disney acquired sports streaming service Fubo, and while that merger is under antitrust investigation, it’s silly to assume any merger would be challenged under this administration. ESPN also acquired the NFL Network, and has consolidated broadcasting power over college football. The NBA has signed a significant streaming deal with Amazon, while MLB is streaming over Apple’s streaming service. The net effect is that it costs thousands for a hardcore sports fan to follow the professional teams he or she might have watched twenty years ago for much less, or even for free. Then there’s gambling. I don’t want to offer too much here, since legalized gambling is its own very serious topic, facilitating addiction, domestic violence, and social despair. We did a podcast on DraftKings and FanDuel last year. But across sports, gambling is attacking the integrity of the games. Part of the deal with the cultural public utility model of sports is that we all acknowledged that cheating was wrong. Sports was a touchstone to promote vigorous competition, with integrity. But no longer. “In the past year, five players, one umpire and one translator have been suspended, banned, fired or imprisoned for gambling-related activity,” wrote journalist J.R. Moehringer, “and those are just the ones who’ve been caught.” Athletes now gamble, leagues are taking huge amounts of money from gambling sites, and the message is clear. Cheating is fine, just don’t get caught. Finally, there’s college athletics. And this one’s more of an optimistic story. For a long time, college athletes in football and baseball at major programs had full-time jobs as players, while only being allowed to get an education instead of monetary compensation. This dynamic made it very hard for poor athletes, and was fundamentally unfair. Since the Supreme Court decision, however, top college athletes are getting paid. That said, there are many college sports that aren’t profitable, and those were cross-subsidized by popular football, basketball, and baseball programs. These payments are draining that subsidy. One result is that Congress, led by conservative Republicans who are generally happy with college athletes getting paid very little, are pushing the SCORE Act, which would essentially restore control to the NCAA. It’s impossible for one person to keep up with all of the action in sports, labor and antitrust, but that’s my brief tour of that world. I left a lot on the cutting room floor. And that’s because I want to get back to the big theme, that sports, which used to be a cultural public utility, is now a central way for oligarchs to project prestige. With the fall of the traditional media and the rise of dominant entities like ESPN, there’s very little investigative journalism. But that’s changing too, since there is a hunger for stories about power in sports. And this week, we got such a story, and it goes straight from the NBA and the billionaire world to the heart of the Democratic Party. Sports, the Corrupt Superrich, and Democratic InsidersOne of the best investigative journalists in America these days is an independent podcaster named Pablo Torre, who has published a series of groundbreaking stories on the rot and corruption in professional sports. In June, he got ahold of documents from the National Football League showing that the NFL was suppressing the wages of its top players. What was shocking is that they were keeping that fact secret with the collaboration of the NFL Player’s Association. We had him on our Organized Money podcast to discuss what he found along with former Biden Antitrust chief Doha Mekki; it’s really worth a listen. This week, Torre published another story, this one with an explosive allegation about ex-Microsoft monopolist Steve Ballmer, the sixth richest man in the world and the owner of the L.A. Clippers. Torre got documents and sources implying Ballmer orchestrated a scheme to get around the National Basketball League salary cap and secretly funnel money to star player Kawhi Leonard. And he did so with the help of two high-profile Democratic insiders, one of whom is now in jail. Ballmer, so goes the allegation, funneled the money through a Democratic-aligned company called Aspiration Inc, an eco-friendly financial institution that planted trees to offset carbon emissions. Ballmer invested $50 million in Aspiration, and Aspiration in turn had a secret set of deals with Leonard to send him $48 million in cash and stock in return for doing no work. Aspiration went bankrupt earlier this year, and Leonard’s payday became public in the bankruptcy filings. And that’s where this scheme connects to the Democratic Party policy world. Aspiration itself was founded by two high-profile Democrats, donor Joe Sanberg and former Bill Clinton speechwriter Andrei Cherny. It included board members such as Ben Jealous, the former head of the NCAAP and Sierra Club, and Ibrahim AlHusseini, an early investor in Uber and a board member of anti-war group CodePink. Earlier this year, Sanberg pled guilty to wire fraud. His co-founder Cherny, who signed Leonard’s contract, resigned as CEO of Aspiration in 2022, and has not been implicated in legal wrongdoing. The interesting wrinkle is that Cherny is the organizer of Project 2029, an attempt to craft a policy agenda for the next Democratic administration. And that’s not just a random project, it was unveiled in the New York Times, and has a “Who’s Who” of centrist notables, such as Biden domestic policy advisor Neera Tanden, former National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, New America’s Anne-Marie Slaughter, Third Way’s Jim Kessler, and Brown University’s Marc Dunkelman. To what extent is Cherny involved in this scandal? That’s not clear. We still haven’t heard publicly from Sanberg and Cherny, or Leonard. For my part, I asked those five participants in Project 2029 for their thoughts. None responded, which isn’t surprising. They haven’t done anything wrong, and there’s no upside to commenting on this story. That said, the most charitable interpretation is that Cherny showed extremely bad judgment, which is not unusual for Democratic insiders. It’s a story that’s still developing. The Clippers have denied what Torre wrote, the NBA is investigating, and NBA Mavs part-owner Mark Cuban went on Torre’s podcast to defend Ballmer. That said, Ballmer is a rule-breaker extraordinaire; he made his $150 billion plus fortune as the number two guy behind Bill Gates, the original Microsoft monopolist. He also got fined for circumventing the NBA salary cap in 2014, and even broke rules to bring in paid ringers to improve his son’s high school basketball team in Seattle. I don’t know if this story is true, or if it could really damage Ballmer. But it’s certainly the most heat he’s ever faced as a public figure. In some ways, in today’s oligarchy, sports is the only place the superrich are ever really in the spotlight. Americans love sports, they pay attention to things like salary caps and ownership structures in a way they don’t in the rest of corporate America. They often think they could do a better job managing a team than the random billionaire who owns it, whereas few think they could, say, run Google better than Google CEO Sundar Pichai. So this story, which isn’t abstract, but is about a scheming billionaire allegedly trying to cheat at basketball, tells the story of modern America in a way that everyone finally understands. And now, the rest of the round-up. There’s some good stuff in here. The FTC unsurprisingly ended its campaign to ban noncompetes. Some state enforcers asked a judge to investigate the Trump Antitrust Division - and it actually might happen! And big tech CEOs embarrassed themselves at the White House. There’s even a jump cut of billionaires saying ‘thank you’ to Trump. All after the paywall... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |