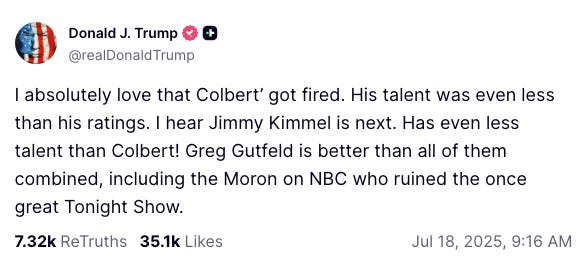

On Jimmy Kimmel: It's Time to Destroy the Censorship Machine and Repeal the Telecommunications Act of 1996In 1996, Bill Clinton set the stage for what Donald Trump is doing now by creating a censorship machine of consolidated media, broadband, and tech firms. It's time to break it apart.Yesterday, comedian Jimmy Kimmel was pulled off the air by Disney/ABC because of some mild joke he made about slain conservative activist Charlie Kirk. Or rather, that’s the excuse, because two months ago, Donald Trump, in gloating about Stephen Colbert’s firing which resulted from a merger that his administration approved, tweeted that “Jimmy Kimmel is next.” What is happening with these firings is obvious. With Colbert, the Federal Communications Commission had to approve the takeover of Paramount by Trump ally Larry Ellison, so as part of the process, Ellison’s buying group had the late night host fired, and also put a conservative minder in charge of CBS News. In Kimmel’s case, there are multiple deals at issue. For Kimmel, it’s more explicit. On a recent podcast, Carr made it clear that he would use his authority to enforce speech codes.

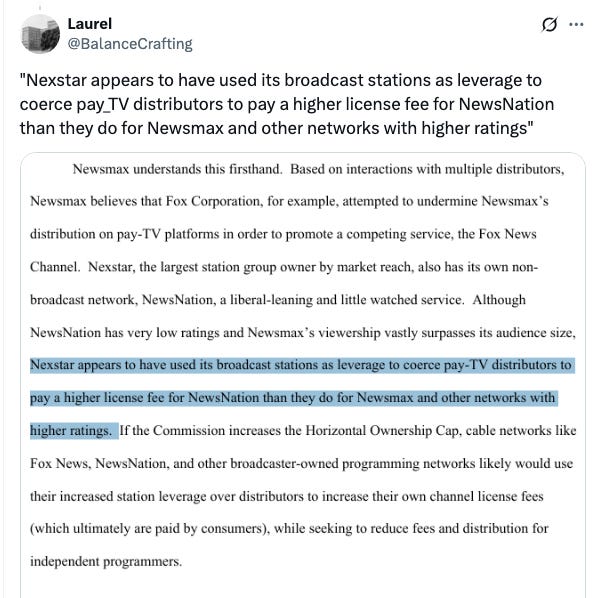

A few hours later, Nexstar and Disney acted. Why? Well Disney, which owns the ABC network, is in the midst of a merger investigation of sports streaming site Fubo, which the Antitrust Division can challenge. More importantly, Nexstar Media Group, which owns 200 local affiliates, demanded Kimmel be pulled off air, and that he make a personal donation to Kirk’s political group. Nexstar “is in the middle of a $6.2 billion merger with media company Tegna,” which “remains subject to regulatory approval from the FCC, currently chaired by Brendan Carr.” We can all connect the dots here. Axios did a useful round-up of the broader context, which is the roll-up of media properties by oligarchs over the last few years. In 2022, Elon Musk bought Twitter, Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post and killed a Kamala Harris endorsement, LA Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong blocked his paper’s endorsement of Harris, Univision got bought by a Trump-friendly outlet, and the Baltimore Sun did as well. Apple, Google, and Meta CEOs have all moved in more Republican directions, in Meta’s case explicitly settling with Trump for millions of dollars over deplatforming allegations. And now Trump ally, Oracle’s Larry Ellison, is trying to buy CNN-owner Warner Bro. Discover, and potentially TikTok. While this kind of political behavior is disturbing, it’s important to see that there are really two separate problems. The first is Trump’s choices, and he is seeking controls over his critics. The answer to an elected leader doing these kinds of things is ultimately elections. The public must express disapproval, and if they do not, then that is that. Elections aren’t my forte, so I’ll leave that to others. The second problem is that the tools exist for Trump to engage in a coercive censorship regime because Bill Clinton and a Newt Gingrich-led Republican Congress helped consolidate the media with the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which supercharged a wave of media and telecom consolidation kicked off by Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. As More Perfect Union noted, “In 1983, 50 companies controlled 90% of the U.S. media market. That number is now down to 5.” If the ability to wield power over content exists, it will likely be purposed, and Trump isn’t the first one to do it. Those of you who have read BIG for years know I’ve observed that censorship relies on consolidation to work. It’s not that there can’t be attempts to exert political control in decentralized media ecosystems, it’s just that it doesn’t work very well. If there are a lot of newspapers, controlling what one of them says doesn’t much matter. If there is one newspaper, or multiple newspapers controlled by one entity, then controlling that entity is inherently censorship. Editing is what someone does when there are lots of channels of discourse, censorship is the same activity when there are very few. Even old laws against obscenity relied on things like having one book distributor in a state, placing liability on that distributor. Why was the 1996 law so important? The fundamental thrust of the Telecom Act was to overturn New Deal restrictions on media consolidation. That law changed strict bright line media ownership rules that prohibited acquisitions of local stations by chains, and moved them to a discretionary system where regulators could approve such acquisitions, which they did and are doing now. It also, not coincidentally, laid the foundation for broadband monopolies with its deregulation of telecom providers, and big tech, with Section 230 that disallowed a whole suite of common law rules from applying to platforms. The effects of that law were striking, almost immediately. It’s hard to remember now, but in the aftermath of 9/11, conservatives and a rapidly consolidating media sought to control the speech of anti-war liberals. George W. Bush said almost immediately after the attacks that you are “either with us or against us,” which was taken to lump together Al Qaeda and domestic critics of U.S. policy. And those signals were received by the media ecosystem. Large swaths of pro-George W. Bush commentators, like Andrew Sullivan, called liberals traitors, “the enemy within the West itself—a paralyzing, pseudo-clever, morally nihilist fifth column that will surely ramp up its hatred in the days and months ahead,” (which he later chalked up to excess emotion). The popular TV host Phil Donahue, then on MSNBC and the only major antiwar voice, was “fired because—as the leaked internal memo said—Donahue represented ‘a difficult public face for NBC at a time of war.’” This was a few years after the Telecom Act, and while we were in the midst of a giant consolidation wave. But even so, McClatchy, a newspaper chain, did do important reporting criticizing the bad intelligence that led us to war. That would not happen today, because those newspapers are mostly gone, their revenue taken by Google/Meta. Courts have further weakened regulatory authority and the FCC has undercut what rules do exist, leading to a wave of further mergers. Nextstar and Sinclair have rolled up what used to be local broadcasting outlets, leading to even conservative outlets complaining about monopolistic behavior. These roll-ups happened under both parties. Obama allowed NBC to buy Comcast, and a judge approved the disastrous AT&T-Time Warner merger that Trump in his first term rightfully challenged. Here’s a piece I wrote in 2018 after that decision, in the then-meaningful site Buzzfeed, about the emerging tools for authoritarianism. And that merger did explicitly lead to censorship. Here’s Adam Conover, in 2022, describing it.

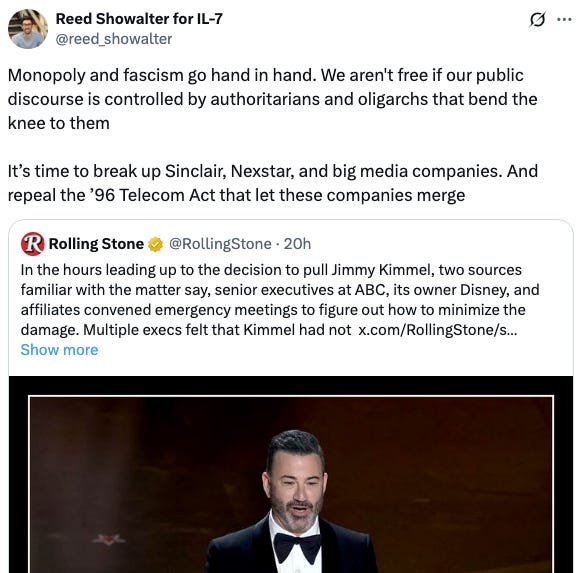

There are many other examples. In 2008, for instance, Comcast refused to run political advertising that included criticism of a politician who had helped immunize the firm for facilitating unwarranted surveillance, Chinese censors routinely control American media content, Facebook used explicit censorship to build its data-invasive business model, big tech de-platformed Trump, and Facebook executives also told Bernie Sanders what he could and couldn’t say on his Senate Facebook page, if he wanted to reach his followers. Today, turning what used to be a network for friends and family to connect into AI slop is its own form of speech control, and that’s not even getting to TikTok. We could find similar examples with Google, Amazon, Sinclair, and most other important institutions of public communication and media. The Biden administration was slightly different. They actually did block some media mergers, such as Standard General’s attempted takeover of Tegna, or Penguin’s purchase of a division of Viacom, Simon & Schuster. Companies like Nexstar and Disney eagerly sought to combine, but couldn’t because they were afraid of litigation from antitrust enforcers. Biden didn’t try to restore any broad media laws, but there was a shift in enforcement. Under Trump, these guys can violate antitrust law and just pay a speeding ticket, kicking a couple of unprofitable liberals from their companies. At any rate, there are two approaches to trying to address our system. The first is to associate the problem solely with Donald Trump, and to focus on the bad regulators doing bad things. That’s essentially the approach of Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries, who offered a statement calling on Carr to resign and suggesting this decision was an “act of cowardice.” Same with Chuck Schumer, who called Carr one of the “greatest threats to free speech America has ever seen.” The premise here is we need good regulators to do good things, angels to run the systems versus devils. Jeffries pledged to investigate if the Democrats win the Democratic majority. And he’s setting up the Democrats in 2027 and in 2029 to do absolutely nothing about corporate consolidation in media, if they win. That means that corporations engaged in aiding Trump have zero incentive to resist, because they know they will not be penalized if they go along with him. More fundamentally, Jeffries’ view reflects a superficial understanding of freedom, because he sees nothing wrong with retaining a system with the built-in capacity to arbitrarily coerce Americans based on speech. There are some indications of a different approach. Antitrust lawyer and Congressional candidate Reed Showalter, for instance, called for restructuring the media. But the Democratic Party leadership broadly speaking is adopting the same approach conservatives took when they perceived liberal censorship in the early 2020s. Donald Trump is their angel, and now they seek to punish the devils. I’ll note that Conservative perception of a censorship regime arrayed against them wasn’t irrational. There were corporate attempts at speech control over things like Hunter Biden’s laptop and Covid vaccines, and there was a significant chunk of liberals who wanted to focus on disinformation and content moderation. But the right also overstated what happened. At no point did Biden use antitrust or regulatory choices, as they are with these firings. When the Hunter Biden laptop coercion happened, Biden wasn’t even President, Trump was. Eventually, Elon Musk opened up Twitter internal records to a team or journalists, and they found nothing explicitly linking decision-making on law enforcement under President Biden to demands over content. It was things like a government official yelling at media official and asking him or her to moderate posts on Covid vaccines, without any underlying threat. And though obviously intimidation tactics are bad, even the conservative Fifth Circuit had a tough time figuring out what was illegal about it. That court offered a mild remedy. The Supreme Court felt even that remedy went too far, and asserted Biden hadn’t overstepped the law. (For what it’s worth, I mostly agreed with the Fifth Circuit). The broader dynamic at the time was that everyone just accepted the reality of dominant tech and media platforms, and liberals and conservatives were fighting about how monopoly platforms should censor. They intuitively got that whatever Mark Zuckerberg chose was not “content moderation,” but censorship, because Facebook is so dominant. Zuckerberg didn’t like this situation; he wanted to be an editor, but wound up a censor. It turns out that putting anyone in charge of a consolidated system inherently bending towards censorship ends up where we are now. If you create a corporate structure premised on the ability to arbitrarily coerce people over speech, it simply will be used. So to take away that structure, we have to undo the damage of the 1996 Telecom Act by repealing it, as Showalter suggested. Politically, that can’t happen right away, since the majority in Congress and the President would oppose doing so. But the thinking about how to do so needs to start now; if a minority party is to win power, they have to define their agenda, and that definition leads to governing. If Jeffries pledges nicer regulators and nothing else, that’s all that’s possible. If they pledge a restructuring of the corporate media, then that becomes possible, especially in a recessionary environment. And media and tech outlets will see the writing on the wall, and recognize there are costs to going along with overt political speech controls. Now, obviously it’s not 1996 anymore, Google wasn’t even founded until 1998. So to do this repeal, we have to restore the older principles of the New Deal system Clinton tore down, and articulate them in the context of today’s business and technology environment. In other words, we have to propose laws that de-concentrate media and communications platforms by offering bright-line rules. We must also restore regulatory power that courts have stripped. And these must apply to new areas like artificial intelligence, search, social media, and so forth, as well as older media systems. Let’s call it the End Corporate Control of Speech Act, or the New Communications Act. A bill like that needs to incorporate a lot of the thinking that has gone on in the last fifteen years. Here are some of the elements that could be incorporated. While this list isn’t complete, the goal of each of these proposals is, like the original Communications Act in 1934, to de-concentrate our media and communications systems and ultimately get rid of the ability of corporate executives or political leaders to easily engage in coercive arbitrary behavior.

I’m sure there are more, but that’s the mix of policies that are mostly baked and ready to go in addressing corporate control of speech. Still, is any of this stuff possible? I think so. While the media and tech world is highly consolidated, there are reasons for optimism. Americans no longer trust our institutions, and that’s pretty reasonable, since those institutions are obviously not trustworthy. CBS News, for instance, while powerful, just isn’t the force it used to be. Liberal elites are also having to stare oligarchy in the face, instead of gently mocking fear of the superrich. Telecom deregulation showed up in an episode of the The West Wing in the early 2000s, and the message to liberals was that there were so many channels, who cares who owns what? Just a few years ago, Chris Cillizza published this article, which was fairly common when someone expressed a fear of oligarchy and media consolidation. That is self-evidently absurd. Another reason for optimism is that a new media ecosystem has started to emerge and fill the trust void, and the public is increasingly interested in a different set of authentic voices. There are plenty on the right, people who are independent and successful at it, like Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson. There are podcasters like Theo Von and Joe Rogan. But it’s happening everywhere. Pablo Torre has taken the sports world by storm with an independent investigative podcast, breaking through because of the decline of reporting in that space. Similarly, Drop Site News, Zeteo and Popular Information routinely break news in the political realm, and Breaking Points is part of a long list of influential political talk shows existing outside this increasingly decaying media infrastructure. Substack itself is part of a set of newsletter platforms attempting a route around social media giants. The demand is there for something different, because Americans are a democratic people. That said, I don’t want to overstate the new ecosystem, because there just isn’t the financing available to do the large scale reporting that used to characterize the American media scene. Most money is still being harvested by monopolists. But if we can restructure the incentives through law, there’s no reason we can’t have a much better and more open media and communications environment. The tools that exist now to build it are spectacular. And let’s not lose sight of the lesson we are learning right now. As media and tech firms make decisions to consolidate power for themselves and Trump, the fairy tale that Abundance co-authors Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein tell each other, that oligarchs can be nice and good, is revealed as just that, a fairy tale. Ultimately, corporate consolidation is necessary for authoritarianism to flourish, and the heart of authoritarian politics lies in the corporate boardroom. And we are seeing this dynamic explicitly. Whether we learn the lessons is up to us. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |