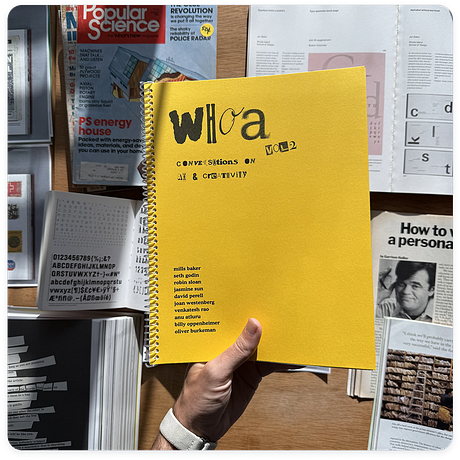

A conversation with Seth GodinWhat people will pay for, the talking dog theory, and why he's being more creative than he has in 20 yearsIn case you missed it… we released our annual zine: Whoa, Vol. 2: Conversations on AI and Creativity. Over the next ten weeks, we’ll be releasing one conversation here each week. If you’d rather savor instead of scroll + want early access to all ten conversations, including David Perell, Oliver Burkeman, Robin Sloan, Venkatesh Rao, Anu Atluru, and more… grab the physical + digital zine. This series is made possible by Mercury: business banking that more than 200k entrepreneurs use and hands down my favorite tool for running Sublime.Companies are only hiring AIs. You need VC money to scale. This economy is bad for business.If you’ve fallen for any of these oft-repeated assumptions, you need to read Mercury’s data report, The New Economics of Starting Up. They surveyed 1,500 leaders of early-stage companies across topics including funding, AI adoption, hiring, and more. - 79% of companies who’ve adopted AI said they’re hiring more, not less.- Business loans and revenue-based financing were the top outside funding sources for accessing capital.- 87% of founders are more optimistic about their financial future than they were last year.To uncover everything they learned in the report, click here.**Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.A conversation with Bestselling Author Seth Godin

The edited transcript:Alex Dobrenko: Alright. Shall we get into it? Seth Godin: Seth here for you, sir. AD: This is, broadly speaking, a conversation about creativity and AI. From what I gather, it feels like you're pretty pro-AI. Does that feel right? SG: I think it's more interesting to talk about it like it's the weather. You can be pro-snow or anti-snow, but if it's snowing out, it's still snowing. I'm glad there are electric typewriters instead of manual typewriters. I'm glad there are spell checkers. Does all the disruption that this is going to cause matter? No. Here's this tool, and I'm playing with it joyously. I'm well aware that people can make arguments all day long, and it's just a waste of time. AD: So you feel like there's not much use in those arguments because it's here. SG: Yeah. When iPhone photography came along, painters were furious, and so were wedding photographers. The fact is, most creators spend very little time actually creating. We spend most of our time doing tasks. Some of those tasks include getting published, some include sorting our files. There's a long list, but the actual number of minutes per day that you're doing something profoundly original—I've never met someone who does that more than an hour a day. I'm up to seven hours a day because one of the things that's happening for me with AI is there's no one to slow me down and no one to say no. A lot of people who get paid to do tasks are stressed because AI is going to take over their tasks. There's a long history of that in art, creativity, and innovation, and it's going to happen again. AD: I love this idea of going from one hour to seven hours of creating. What does that look like for you? SG: Let me give you an example. I used to be a book packager. My job was to invent complicated books that individuals didn't have the resources to make. I did young adult novels. I did books on gardening. I did a book a month for ten years and had ten people who I worked with. A book like the Information Business Almanac took five of us a year to make. Five weeks ago, I got an idea to create a deck of cards. Each card would have an icon on it that would remind you of someone's body of work. If you scanned the QR code, it would bring you to an artifact in Claude that would have an endless conversation with you based on that body of work. Imagine a patient, inquisitive coach who talks you through everything they know about Warren Buffett's financial approach or everything that Annie Duke has to teach about making decisions. I then illustrated the entire thing, wrote all of the artifacts, got all the QR codes, laid out the whole project, and sent it to the printer in ten days by myself. I've since followed it with two more decks that I'm going to announce in a few weeks, and that's only in the last three weeks. So yes, I get that I have an enormous head start in two ways. Number one, I don't have to sell something today to pay the bills tomorrow. And two, it's not my first rodeo. I know what it takes to bring something into the world. But if I wanted to go faster, I could write a book every three weeks. The idea that I have many partners, each with different skill sets, who are willing to work on things without pushback—unless I ask for it—is extraordinary. So I am being more creative now on a per-minute basis than I have been in 20 years. AD: It's a very practical approach, which I like, because so much of this conversation gets very theoretical and heady, rather than just, "Let's do stuff." SG: I made a Udemy course last week about how to think about AI. One way to do it is to say, "How can I lower my costs? How can I become more efficient?" That's what almost every big company is doing; they're racing to the bottom. The other way to do it is to say, "How can I work harder? How can this put me on the spot to do things I might be uncomfortable with?" And that's what I'm trying to do. If you say, "Here's this AI tool, and I'm going to give it my copy and ask it to make it slightly smoother," that's a fine tool to save you a couple of hours of work, and it leads to the world turning into mayonnaise. I'm not interested in that. That's why it doesn't write blog posts for me. But what it does do is I'll give it a chapter of a book or a blog post and I'll say, "You know, there's something wrong with my argument here. Give me some really direct pushback on this." And it will highlight something, and I'll go, "Oh, yeah, I guess I gotta fix that." Then I'll have to spend two hours doing more work to make it better. Well, what happens when we add that to every doctor's office, every therapist's office, every geologist's office? That can't help but make things better. AD: There's a fear I think for a lot of writers and creative people. Does it bring up insecurities or fears for you? SG: If we're going to have an ego contest, I'm going to win, right? I would start by saying most writers don't have a voice. I have a voice. I have a style. I've written 4 million words. Claude has read all of them. Most people who write, write simply to be understood. It's specific but generic, and why isn't AI going to be better than people at that? Of course it is. When I first asked AI about me and my writing, I was secretly hoping it had read everything I had read. I was delighted to discover this is true. I want it to steal all my work—that's why I wrote it: to become part of the culture. And if we get to the point where I don't have to write my blog anymore as a service to other people, I'll probably write it for myself. If we look at something as prosaic as instruction manuals, everything from IKEA to how to use software, they're inherently flawed. They lack empathy. They frustrate all the people who read them. AI should do it. The purpose of an instruction manual isn’t to give a job to a technical writer. It’s to help the person who’s reading it. AD: What's something about AI and the conversation that feels underexplored to you? SG: I don't think my peers, regardless of age, are using it nearly as much as I expected. When I bring it up at dinner, lots of people who do what I do, their eyes glaze over and they don't want to talk about it. I'm stunned by this, but I felt exactly the same way in 1995 when I was talking about the internet. But for people who are listening to this who already get most of the joke, I think there are two or three hacks that are really helpful. One is loading up AIs with large pieces of existing writing and data. Like, "Here's every email I've had back and forth with someone over the last year." That sort of loading up with context is huge. I gave it a 40-page business plan that five of us had written over the course of six months and said, "Give me a two-page memo analyzing this from the point of view of a Harvard MBA." It was brilliant. It saved us an enormous amount of time. And then, going with that, just simple little things like taking a picture of all your bookshelves, or a picture of all your storage closets, and putting them in a folder. Every time you're looking for something, just upload it and say, "Where's this?" and it will tell you. AD: Why do you think people glaze over when you bring this up? SG: When in doubt, look for the fear every time. They sell Supreme T-shirts at a store in Manhattan. People wait in line to pay $90 for a T-shirt. Why are they doing it? Look for the fear: status, affiliation. Sometimes we call it greed or seeking profit, but that's also a form of fear. I'm talking about people with 10 million views on their TED talks, people who have had multiple bestsellers, because people who lead deep down feel like imposters. Because we are imposters. We're doing something that hasn't happened yet, doing something that hasn't worked yet. And when AI shows up and there's some 22-year-old whippersnapper in Ukraine who's so much better at it than you are, what do you do? It's easier to just say, "This'll pass. This is like Dogecoin; it's going to go away." But it's not. This is the biggest change in the world since electricity. AD: It sounds like you don't do a lot of stuff with AI out of fear. So what do you do things out of? Is it love? What else is driving people? What's driving you? SG: What drives me is the delight of solving interesting problems. But it has a flip side and a cousin, which is we all know we're going to die. And one symptom for me of pre-death is calcification. You know, the "Hey, kids, get off my lawn." So for me, there's the delight of figuring stuff out. Making these decks has made me so happy. It's been really exciting, even if no one buys one, it's fine. It's been joyous for me. It's good to feel that thrill 50 years after I first started playing with computers. AD: What is your personal AI thesis? The core belief that drives all your decisions around these tools? SG: It's the talking dog thing, which has two parts. Part one is if you meet a talking dog and its grammar isn't very good, don't forget that it's still a talking dog. It's still a miracle. But number two is just because a talking dog said it doesn't mean it's important. AD: "The medium is the message" is the thing everybody says all the time. If AI is the medium, what do you think the message is? SG: Okay, so what was McLuhan trying to say? The kind of stories that run in newspapers are different from the kind of stories that run on the evening news, which is different from the kind of stories that run on the internet—even though the world is the same. We report it differently because of the medium. It's not an accident that pop songs are 3.5 minutes long. They're 3.5 minutes long because that's how long a 45 holds of music. We came to understand that a pop song needs to be 3.5 minutes long because of the way Edison invented the phonograph. So if this medium of AI is showing up, how is it going to change the way we deliver messages? Go look at the explore page of Midjourney, and what you notice is, even though Midjourney is capable of quite a few ways of expressing itself, it all seems to be this near sci-fi robot, soft porn. Because the medium encourages that. It doesn't mean it's going to stay like that, but we should be aware of its biases. We should be aware of what feels natural to it. I'm hyper-aware of that all the time. That's part of it. So what ChatGPT did was they exposed that. Claude put a layer of friendliness on top of it that hid a little bit of its non-humanity and its biases. And I fell for it, and happily, because I want to work with something that's pleasant. So, long answer to your question: we need to think about what people are going to pay for. Because creators have to make money, and they're not going to pay for pretty good nonfiction books anymore. The value of those is going to go to zero. They're not going to pay, even with ads, for sort of funny one-minute videos. Not going to pay for that. They're definitely not going to pay for $200 million blockbuster movies that aren't very good, because there's nothing in the new Superman thing that I couldn't make in Midjourney in a minute and a half. We're going to have to figure out how attention is going to be adjudicated. What is going to get made to fit into that attention hole? AD: What do you think people will pay for, if you had to bet? SG: I think in the medium run, people are going to pay for community. I think the loneliness epidemic is real. And some people are going to pay AI for a substitute for that. But most people who can afford it are going to find circles that are worth being part of. But the value of scarce content is going to plummet to zero. AD: What advice would you give people who want to use AI thoughtfully? SG: I think you should begin by creating a series of documents in Word or TextEdit and describe your situation in as much detail as you can. Go on for pages. Write a five-page autobiography. Include your resume. Make a different document with all of your health history. Make another document with relationship history for business or personal things you're dealing with. Then, because remember, you could never do this with a person, when you're going to ask an LLM a question, upload the thing. No one's going to sit there and listen to you read five pages of background when you ask them a question. But AI will. So go spend an hour talking to Claude about that. And don't listen to people on podcasts. Listen to Claude, because it's read your five pages and I have not. You don't have to do what it says, but you have to agree or disagree. And if you disagree, ask new questions. When I think back to what got me into the book business, the late Byron Preiss worked with me when I was in the software business. He knew I was leaving the company, and he said, "You should be a book packager. You'd love it. As soon as you quit and move to New York, call me and I'll get you started." And I did it. I quit, and I moved here because one person said this was the job for me. Then Byron ghosted me, and I never spoke to him again because he didn't answer any of my calls. Now here I was, committed. This is a lousy way to pick a career. It's so much easier now to not get a guarantee, but to understand the lay of the land, to understand where the opportunities are. AD: Do you have any particular tips for using LLMs? SG: The one I wish I had known about six months ago is this: if you find yourself in a frustrating conversation or it's hallucinating or doing something that's not helpful, shut the window and start a new one. As a human being, this feels really rude and inappropriate, and I don't know why it works, but it's spectacular. Sometimes the new one will be this eager, smart, cooperative intern. And sometimes it'll be this lazy jerk. And it's the same program. What I've discovered is I don't have to apologize. I don't have to say goodbye. I just close it, start over, and I've got all my docs. I reload the docs, and then we're off to the races. So that's my biggest hack. The other one is that I regularly ask ChatGPT to help me write Midjourney prompts, and I ask Claude to help me write ChatGPT prompts. And then we'll boil it down to a really good prompt, and I'll paste it into the other one. I find that is less recursive than pasting it back into itself, because when I paste it back into itself, it seems to have shortcuts in there that I didn't intend. So that's a big part of it. The other one is being loquacious about what I want it to be like. We were taught by Google to use as few words as possible because Google was supposed to be a miracle. It would read your mind. So, when I was running Squidoo, if you typed "laptop bags," two words, it would take you to the Squidoo page on laptop bags, which was the perfect place to go. And it was ten screens worth of links and prose about which kind of laptop bag to buy. That's not a good way to talk to an LLM. Instead, you can say things like, "Memento is one of my favorite movies, but I also like the production values of The Matrix and the sense of humor of The Usual Suspects. Please give me five movies I haven't seen yet." If you just say, "Give me five movies," who knows what you're going to get? But if you give it these anchors, what I have found is that certain anchors set it up almost instantly. If an anchor is Kevin Kelly, or Seth Godin, or Baratunde Thurston, or Patti Smith, those are great anchors. In just two words, you sort of know where it's going to go after that. So you say, "If I was asking Kevin Kelly for career advice based on my resume, what would he tell me to do?" That's a really useful prompt. AD: What do you think makes for a good anchor? What makes those names better? SG: I think you need to have someone who has a significant body of work, is able to be read, and who is distinctive enough that you could make a parody about them. There are plenty of people who have written semi-funny movies, but Woody Allen is somebody that instantly you can parody; he instantly reminds you of somebody. So when you can find those sorts of voices, whether it's my friend Jill Greenberg, the photographer, if you say to Midjourney, "in the style of Jill Greenberg," it knows exactly what to do with it. Richard Avedon is the same way. AD: Did you actually do that prompt about the movies? SG: I didn't do that one. But I was looking for the right kind of vintage movie to watch with my wife, and it recommended Charade, a movie that I had never seen. It's next in the queue, but the reviews look perfect. I never would have picked it. AD: Where do you think it keeps coming up short? SG: Very clearly, for me, the place where it's coming up short most glaringly is it has no idea what to do next. This is part of why I think it's terrible at writing anything funny, because it knows how to do a one-liner. But if you ask it to write a Seinfeld script, it's absolutely useless. That's hard work. Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld would have new people in the writers' room every year, and these guys would come in with true stories from their life. Like, the Soup Nazi is a real person. Really. Some guy in the writers' room told the story, and the hard work was picking the good stories, stringing them together, then deciding, "We're going to do a deck of cards" versus doing this or that—that's reserved for creators right now. I don't know if that's always going to be true. I think it's a surmountable problem. The challenge will be that there's going to be a period of time where it will be gray goo and crappy stuff, and it needs to figure out good taste about figuring out what's next. The same thing is true for coding. I think if you say to it, "Build me an entire operating system that's better than the Mac," it couldn't do that. But in the long run, my thesis is that all of this is trivial compared to what's going to happen next. The Internet is about connection, between and across people. And for the longest time, everything that worked on the Internet worked because it connected people to each other or people to information they were looking for. So what happens when Claude knows everything there is to know about me, and it knows everything there is to know about you, and we opt in to let it be an intermediary between us and other people in our circle? Something as simple as, I'm about to throw out a whole pile of something because it's useless, and it says, "Wait, wait, wait. Alex was just looking for that on eBay right now." There's a whole new level of intermediary magic that's happening, because there's this sort of confidential slush pile in between us, and it's sorting it out on our behalf to create new connections, new opportunities. Someone's dealing with a problem; someone has the answer to that problem. Magic happens that we believe is only supposed to be coincidental. You're on an airplane and you discover the person sitting next to you is someone you've been wanting to know your whole life. Well, Claude already should know that. So how does that start to perfect the human condition in ways that people can't even imagine right now? The thing that worries me, in addition to all the other things that worry me, is that Sam Altman has to pay back a lot of people a lot of money. And that always leads to organizations becoming evil, the way Google did. Watching Google become evil, shutting down companies like mine, doing things that they couldn't possibly be proud of, that's sad. And I think advertising will accelerate that. I'm hoping we can stay ad-free. AD: Everyone's making predictions about AI. Let's make a prediction about humans. Where do you think humans will be in ten years? SG: Exhausted, slightly broken, with glimmers of hope. AD: Haha. So like we are right now, basically. What question about AI and creativity do you think people are not asking enough? SG: "How can this make my work harder?" AD: Beautiful. Seth, this was amazing. SG: You made my day. |