Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about awe, wonder. impossible colours and how unbelievable things actually happen pretty much all the time.

🎂🎂🎉🎉🎉Welcome to the end of season 7! 🎉🎉🎉🎂🎂

(Sorry about the emojis - I’m desperately trying to pretend I’m not 54 next month. 💩.)

As usual, this was going to be a short-and-sweet season that unfurled into something more sprawling, thanks to all the fascinating scientific side-quests I found myself unable to avoid writing about along the way.

On that note, before we recap all that stuff:

That’s two huge steps towards potentially making life bearable for hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, once these treatments are made accessible & affordable to them. Honestly, I will never tire of this version of the future arriving - as it so often does without the fanfare it deserves.

Anyway, where were we?

The biggest theme over the last 7-and-a-bit months has been the science of the mostly invisible sea of air over our heads, as I introduced here last October. It’s been a lot, and I’ll link to all of it today - which probably means that if you’re reading this in your email, it’s going to be rudely chopped off somewhere below. To get the whole thing, you’ll have to click through to the Web version.

(Just click on the title of this newsletter in your email version, and it’ll open up the Web version in your browser.)

OK! Here’s what Everything Is Amazing has covered since the end of January.

“It’s just before two on an afternoon in early September, and professional aeronaut Henry Tracey Coxwell has just discovered something that’s turned his blood cold.

The balloon he’s riding in with meteorologist James Glaisher has developed a serious fault. As it rose above the countryside around Wolverhampton, it’s developed a slow but inexorable spin - and Henry’s just discovered this has tangled up the release-valve line, the duo’s only way of venting enough gas from the balloon to trigger a descent.”

“This may look like a deep-frozen toupée, hence its name, hair ice - but it’s actually due to a specific kind of fungus (Exidiopsis effusa) that grows on rotten wood. Via a process called ice segregation [PDF], the ice is extruded into these long, thin and incredibly fragile hairs, and then the fungus chemically stabilizes them with something akin to the proteins in antifreeze.

(Its discovery is credited to German climatologist Alfred Wegener, who also originated the hypothesis of continental drift, laying the groundwork for plate tectonics - but Exidiopsis effusa’s role in hair ice formation was only discovered in 2015.)”

“By breaking down around a million tons of airborne organic carbon every year, airborne bacteria sustain themselves by eating the clouds they live in - and they even seem to have a role to play in making those clouds produce rain.

(This also makes every rainstorm an absolute deluge of single-celled life - maybe an unsettling thought when you’re caught in a storm, but that’s because most of us associate the word “bacteria” with “disease” when the reality seems to be that over 50% of the cells in our healthy bodies are bacterial. This makes each of us a united collective effort, comprised of bacteria working alongside human cells, that would put any attempt at human social collaboration to absolute shame. We could be the ultimate immigration feel-good story.)”

“On deck, Beryl could see it coming: a rogue wave, impossible to have predicted, “a great wall of water…so wide that she couldn’t see its flanks, so high and so steep that she knew Tzu Hang could not ride over it.”

This was her last visual image before impact - and the next thing she remembers is floating in the sea, her life-line broken, but when she turns, a miracle: the boat is there, just a few dozen yards away.

It’s lying low in the water, and both its masts are gone.”

“The roughly 3,200 pairs nesting on the Farne Islands (from around 2 million Arctic terns worldwide) follow a similar route every year of their lives. It’s absolutely normal behaviour for them - meaning that this record-breaking tern had probably already done this journey six times already in its life. Furthermore, since these birds can live until they’re over 30 years old, it might be repeating the trip another couple of dozen times over the rest of its lifespan.

That would total around 1,700,000 miles, enough for nearly four roundtrips to the Moon and back - all from a tiny restless creature that weighs less than the average smartphone.”

“Thanks to their amazing sensitivity to infrasound - very, very low-frequency sounds - combined with their awareness of changing air pressure, it’s possible that birds can sense (or even hear!) storms approaching from days and days away – and alter their flight patterns accordingly.

In 2014, golden-winged warblers in Tennessee all scarpered en-masse, just before a huge storm front barrelled in and thrashed the landscape with a total of 84 tornadoes.

Once the bad weather had moved on, the warblers all came back.

So – can’t see any birds at all? Well, maybe forget walking.

Start running.”

“I know the title of this particular newsletter, ‘Let’s All Remember When We Saved The World’, is the kind that will attract clap-backs like “oh stop with the sensationalising, the ‘world’ will be fine, it’s just humans who will find it harder, I hate you climate-change clickbait people.”

To pre-empt a bit of that, let’s look at our world without its ozone layer, which was exactly what Rowland and Molina’s work seemed to predict.”

“Considering the fanatically polarised nature of so much in my social feeds right now, what could I learn - and pass along to you - about creating curious, mutually respectful conversations about even the most inflammatory topics, and maybe even helping change a few minds along the way? How do the professionals handle this stuff, and what can I borrow from them?”

“You loathe trolls, right?

Okay! Then your job is to defy them.

Not to respond blindly out of anger or frustration, and not to be tricked into having your precious time squandered by them, bamboozled into giving away your attention and therefore your power - but to properly thwart them.

Up for that?

Good. Because genuine thwarting requires some forethought, a cool head and a bit of detective-work, as I’m about to explain.”

“Talking about kindness, we usually think of tangible gifts, the kind we get at Christmas or on our birthdays. Or we just boil it back to money. But taking the time to listen and understand are a great kindness too - sometimes a priceless one. They give another person the dignity of being heard, to have a voice that says exactly what they’re saying, instead of what we assume they’re saying.

All of this is fantastically hard to put into practice. Election cycles remain dominated by news media soundbites, social media yelling-matches and everything else that hasn’t worked so well in actually creating conversation. Oh and hey, an extremely opinionated billionaire recently took over Twitter. The yelling will continue.

But as Guzmán says: “whoever is under-represented in your life will be over-represented in your imagination.” ”

“Kish lost his eyesight at the age of 13 months - and he’s 58 now. That’s just under 57 years learning how to perform this astounding feat. He’s been training for it his entire life - so, without attempting to suggest his abilities are anything less than incredible, it’s no wonder he’s so good at them?

As Kish notes in the video, he’s taught himself to form a broad acoustic map of his surroundings, but it’s still nowhere near the fidelity of bats (which can determine distances down to 1 centimetre, which is how they can snatch insects out the air) or of mechanical acoustic location devices like active sonar."

It’s also a very long way from Matt Murdock’s ability to dodge punches or air-ballet his way through a fast-moving brawl. But it’s certainly something - and that something requires Daniel Kish’s brain to be doing things most of ours can’t.”

“As far as I’m aware, I now have two courses of action available to me: go down into the bar-room, sitting there spattered in drying mud, glaring at people until they avert their eyes, warming myself with a glass of the local gut-rot and wallowing in self-disgust. Or I could just accept that I probably can’t feel much colder & more sodden than I do now, so I might as well go explore some more of the Wall until the heating comes on at 4pm.

One of these options is entirely sensible. The other is a course of action it’s hard to justify without making yourself sound unhinged (including 13 years later, when you’ll put it into a newsletter).

I already know which one I’ll pick.

Oh god, Mike. Why are you like this?”

“In 2013, four University of Leicester physics students had a go at working out how feasible this might be, based on current understandings of physics:

the information (in bits) of one human cell: roughly 1 x 1010 (ten billion)

the information needed to transmit a human brain in its entirety: 2.6 x 1042 (there is no name for a number this big, but by contrast, it’s estimated there may be a septillion stars in the known universe which is 1 x 1024 - and when you remember every power is ten times the previous one, it’s best to just stop thinking at this point, make a cup of tea and stand in the garden having a nice, relaxing shriek).

the time it’d take to transfer this information over a 30 Ghz (Extremely High Frequency) signal: around 4.85 x 1015 years. Since it’s about 14 x 109 years since the Big Bang, this means this method would take around 350,000 times longer than the lifetime of the known universe to beam someone anywhere! Efficient it ain’t.”

“Never forget the Rumsfeld Matrix: what you think you know & what you think you don’t know are both massively outweighed by the unimaginable vastness of what you don’t know you don’t know - and there’s a lot of joy waiting for you if you make an effort to discover some of the latter.”

“From that robin’s perspective, with its blindingly fast speed of living, how long in subjective time was it in my flat? Did it feel like it was imprisoned for hours? Or an entire day?

It seems some creatures might be able to adjust the rate that they experience subjective time by boosting blood flow to their brains, or using neurotransmitters like dopamine, so that their neurological processes can speed up without exhausting themselves. This is currently being investigated in relation to humans because of its potential to help folk with dopamine disorders, like ADHD. (One frequently recorded aspect of ADHD is that time seems to be flowing maddeningly slowly.)”

“This is what the best stories do - including non-fiction ones. They’re not just trying to stuff our brains with dates and data. They’re also trying to tug at our emotions (the real power behind our ability to make decisions), to make us feel something so intensely that we can’t just shrug it off as we watch, read or listen our way onwards into an infinity of available information…

In short: good, intimate storytelling helps stir your readers up, in the hope they’ll do something with what you teach them.

Forget this at your peril.”

“In September 2023, geophysicists across the world started picking up a very odd signal coming from the ground under their feet.

A seismometer in the Arctic recorded it. Another in Antarctica registered its presence. It could be detected everywhere - and it wasn’t hard to spot against the normal discontinuous background noise of our planet bending, cracking, heaving and erupting in fabulously complicated ways, because this was a single vibration frequency, as regular as a metronome.

For over a week, the Earth chimed like a struck bell. One pulse every 90 seconds, every hour of every day, for 9 days.”

(A version of this story also blew up on Bluesky and Threads.)

“The distant ancestors of humanity seemed to have fared better than we can, but nowadays our major organs, such as our kidneys and brain, have lost most of their regenerative capacity. As for other parts of our bodies, once they’re gone, they’re gone.

This is a major biological setback that evolution has bottlenecked us into. Just look at the closest living relatives to humans that can regenerate an appendage: lizards, complete with their remarkable and often horrifying ability to detach their tail as a defence mechanism, later growing a new one.

So what could be done to unlock our lost ‘super-healing’ abilities?”

“This is why I’m here, to gawp. To look upwards at this colossal fog-streaked edifice, the product of so many people knowing things I’ll never learn, and doing things I’ll never be capable of doing, and working together in a way that surely would fix everything if only everyone round the world agreed to try it for a change.

As I look upwards, everything else shrinks away to nothing. I forget my aching feet and bruised-feeling shoulders from yesterday’s 26-mile walk to get here, carrying an overladen rucksack. I forget the cold, and my mild headache from forgetting that bitter cold can dehydrate you just as much as scorching heat. I even forget my ever-present anxiety about whether I’ll ever find a way to make a living as a writer (a worry I’ll wrestle with for another decade, until I begin writing an odd little newsletter called Everything Is Amazing.)

For a few astonishing minutes, this is all there is.”

Neuroscientist Dr Susan Barry has just been asked a very strange question:

“Do you think you can imagine what it’s like to see the world with two eyes?”

Her response, in her own words:

“Yes, of course, I can imagine that. I’m a college professor, I teach about it in class. So, yes, I think I know exactly what it is I’m missing.”

Susan was born cross-eyed, which rendered her stereoblind, unable to see with binocular vision. She eventually had it surgically corrected, but only after the age of two - beyond the point where the brain cells involved in binocular vision have learned to work together. For her, despite her eyes now being aligned, her vision remained depthless, nothing between the near and the far. Her view of the world is as flat as it appears to a binocular-visioned person with one eye scrunched shut.

Three months after giving this reply, she sends her questioner back a letter, which covers 9 single-spaced pages and begins with these words:

“Dear Dr. Sacks, you asked me this question, I gave you this answer, and I was completely wrong.”

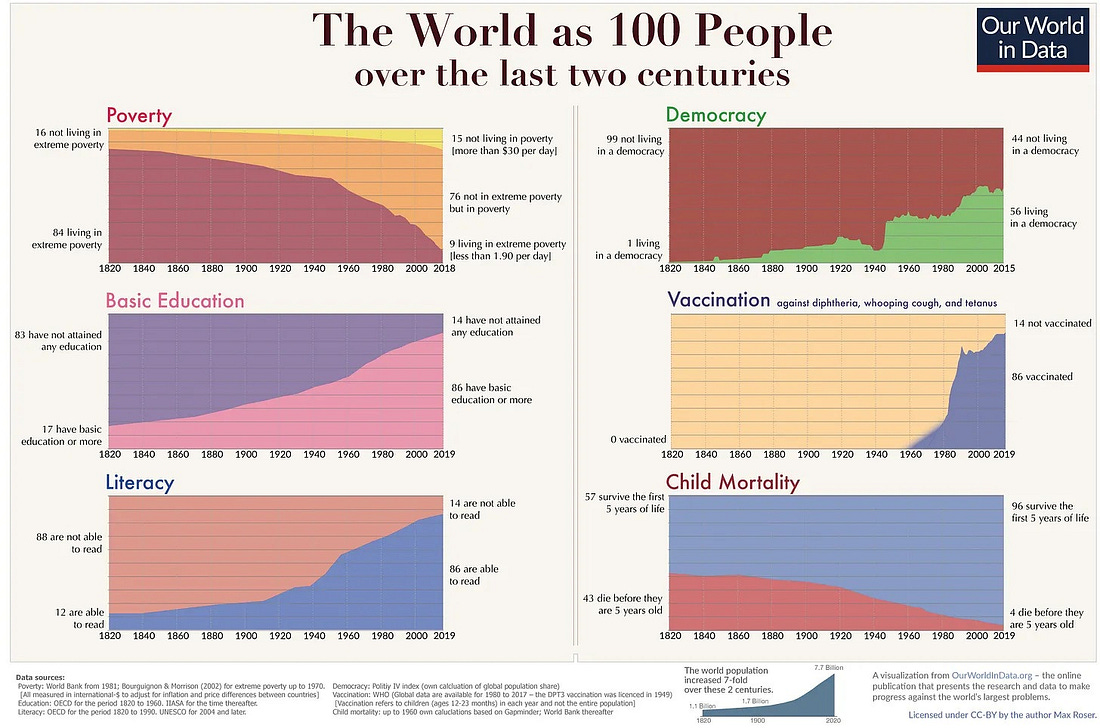

“Medical advances, technological leaps forward that create huge boosts to quality of life, our incredible new abilities to hear and understand each other across vast distances (hi there!) - it’s all absolutely incredible.

It’s also a mess! It’s riddled with all sorts of new problems (alongside the old problems given a lick of new paint), and the struggle to make sure everyone benefits equally is absolutely real. That’s progress for you. It isn’t pretty and it’s often maddeningly unfair in a socially lumpy way.

It’s also just so complicated. Seriously, who the hell knows what is happening, on the whole?

I’m grateful to Sam Matey-Coste for teaching me a few new things about how rapidly the future is arriving when we had a great chat about it recently.

These charts alone (source, via Sam) are so startling:

But there are four big changes in particular in my lifetime, arguably far less consequential than anything in those charts but astonishing in their own right, which I will never, ever want to fully get my head around, because of how much they fill me with such gratitude and wonder.”

Back tomorrow with details about where we’re going next!

Cheers,

- Mike