This is the Sublime newsletter, where we share an eclectic assortment of ideas curated in and around the Sublime universe.

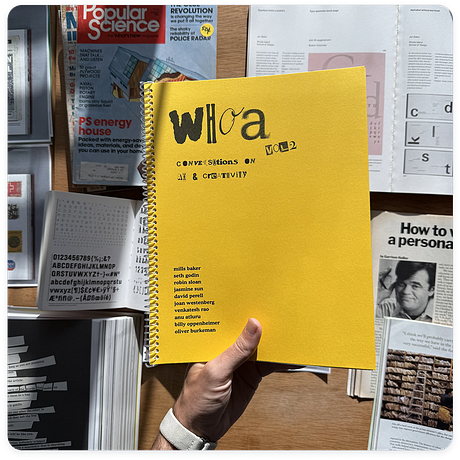

In case you missed it… we released our annual zine: Whoa, Vol. 2: Conversations on AI and Creativity. We’ll be releasing one conversation here each week. If you’d rather savor instead of scroll + want early access to all ten conversations, including David Perell, Oliver Burkeman, Venkatesh Rao, and Anu Atluru, grab the physical + digital zine.

Get your copy

This series is made possible by Mercury: business banking that more than 200k entrepreneurs use and hands down my favorite tool for running Sublime.

Running a company is hard. Mercury is one of the rare tools that makes it feel just a little bit easier.

Every other banking platform makes me feel like I’m doing taxes. Mercury makes me feel like I’m building something. The interface is unbelievably intuitive, fast, and lets me handle everything in one place – banking, cards, spend management, invoicing, and more.

If you’re a business owner of any type, visit mercury.com today and find out why so many of us actually love how we bank.

**Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.

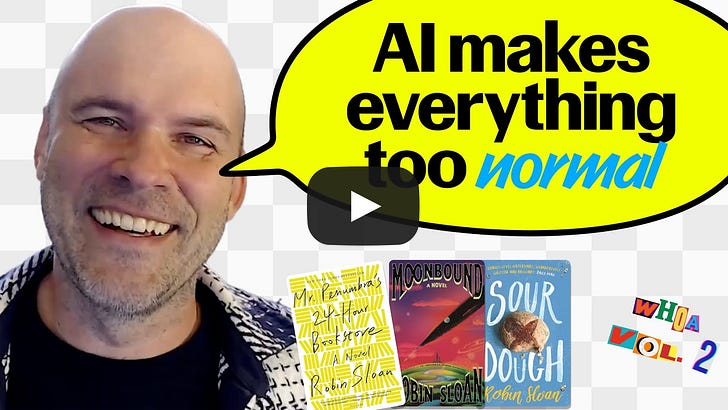

How to describe Robin Sloan? He is the New York Times bestselling author of the scifi novel Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore published in 2012, and Moonbound, which arrived in 2024. But calling him a novelist misses the point.

Robin is something rarer—he codes for fun, worked at Twitter at some point, prints zines on a Riso machine in his office, makes specialty olive oil, and has been experimenting with AI long before it was cool.

This makes him possibly the tech world’s most literate programmer, or literature’s most technical novelist (do these words even make sense?). Either way, he has a unique vantage point that lets him see both the promise and the absurdity of the current moment.

In this conversation, we cover:

What it was like experimenting with GPT back in 2017

Why offline economics works better for artists

Why AI makes everything too normal

What he wishes AI could do but fears it never will

The questions about AI and creativity not being asked enough

His favorite use cases

and lots more…

Or listen on Spotify and Apple.

Alex Dobrenko: I want to start with something that feels like ancient history, that video of you talking about using GPT from like seven years ago. Everything has changed, and you were doing it so much earlier than everyone else. I’m curious, how has that been for you?

Robin Sloan: First and foremost, a confession: I’m often guilty of that classic feeling of “I was into this band way before you guys were.” I’m not proud of it, and I don’t think it’s particularly healthy or productive.

I got deeply engaged with these tools around 2017. I was tinkering with the code and trying to put together models of my own. I went through this whole arc of learning, experimenting, and then building some tools. To tell you the truth, I kind of got burned out. The creative results—what the tools were actually producing for me—ended up being a lot less interesting than the technical part. At a certain point, I had to say, “Well, back to work; I have to write a new book.”

I haven’t quite recovered from that. I still use these new tools and think about them a lot. I do kind of wonder if I lit the firework and watched it burn in the late 2010s.

AD: Could it be that the vibe of the experience just wasn’t right? That’s something I keep running into—I don’t feel great as I’m doing this.

RS: I think that’s right. A lot has changed beyond just the technical capabilities. As these tools became obviously valuable, many people rushed into the industry, and the culture around them changed. Back then, it wasn’t clear they were valuable for anything, so it was just the nerds and the weirdos, which is always fun. I don’t think it’s always wise to say it was better in the early days, but it was more pure.

I think folks who are interested in this stuff now might take for granted that a model is something that can only be trained at essentially a nation-state scale. But back in those days, everything was smaller. It was something you could train yourself. The most exciting thing was imagining what I might put into my own personal model. I spent a lot of time pulling down interesting text. I also thought about the same issues that are front and center for these big companies now: Is it appropriate to use this material? What’s the moral component?

At the time, I had this almost sci-fi vision: Imagine every writer working with their own custom model they had brewed up themselves. You’d say, “Yeah, all the great public domain stuff, and then a little sprinkling of Ursula K. Le Guin, and maybe I’ll put some code in there to give it a more systematic way of thinking.” That was appealing, but that’s not the way it went.

AD: Yeah, I think I would feel a lot better using something that I made myself.

RS: I think so too. Max Kreminski, a great scholar of AI and creativity, wrote a paper about a year ago about AI-written content that doesn’t seem to quite press our buttons. The title of the paper is also its thesis: “The Dearth of the Author.” Not the death of the author, but the dearth of the author. His point is about a paucity of decisions. When you prompt an AI model to write a whole story, do a revision, or write part of it, you’re essentially making one big decision. That’s very different from the real human process of writing, where every single thing is a small decision. The accretion of all those decisions is what gives writing a certain density and value.

The model itself is a series of decisions as well. Back in the old days, when there were no publicly available models and all you could do was train your own, you had to sit and think about it and make trade-offs. There are decisions being made now; they’re just not being made by you, the user.

AD: As a writer, I find myself being very defensive about how this is going to be okay for all of us. One thing I hold onto is that when I’m writing, I’m often trying to do the thing I’m not supposed to do. It’s supposed to be this, but then I do that. I feel like that decision will always be one step ahead, even when AIs get very competent. Like if it’s going to do that, I can always do something a little weirder, and that makes me feel okay. Like I can rest in that or something.

RS: Absolutely. They always talk about a model scoring 99.7% on a test. Well, how about a joke test? I confidently presume the answer is currently no, and I think it stays no for a long time, even at their most capable. This isn’t a moralistic “go humans” judgment; it’s the technical reality. They operate on a probability distribution of data. I love the idea that it’s the comedian’s job to always be headed out to the borderlands. If your punchline is in the distribution, it’s not a punchline; it’s a dad joke.

They always talk about a model scoring 99.7% on a test. Well, how about a joke test? I confidently presume the answer is currently no... This isn’t a moralistic “go humans” judgment; it’s the technical reality. They operate on a probability distribution of data. I love the idea that it’s the comedian’s job to always be headed out to the borderlands. If your punchline is in the distribution, it’s not a punchline; it’s a dad joke.

We’ve seen this happen so many times. AI programs master the perfect New Yorker short story format, and then we all decide the format is busted, and we’re onto the next thing. We know this about art, right? First, you have to master the basic technical skills. Credit where it’s due, AI technologies have ascended that slope, and you can get something that’s very competent. But when you crest over that, you’re still far away from the pinnacle of the great artists of history. As soon as you cross that threshold, you understand that what makes things interesting is the subtle ways in which they are kind of fucked up. I think there’s a courage and a real precision there that, at least so far, does not seem available to AI models.

AD: Yes, bingo. It’s that thing that, as the viewer, you just feel when it’s not there.

RS: Yeah, it’s funny. People say you just have to be more precise in your instructions, that these models can take guidance. It’s interesting and cool that they can, but I’ve heard people say this about novels or poems where the only actual description of the novel or the poem is the thing itself. A good novel or poem is self-describing because it has that density. There are probably some novels and even poems you can summarize very accurately, and those are not the good ones because they don’t have that density.

People say you just have to be more precise in your instructions, that these models can take guidance. It’s interesting and cool that they can, but I’ve heard people say this about novels or poems where the only actual description of the novel or the poem is the thing itself.

AD: That has happened to me so many times. I’ll try to use AI to write an email for me, and I want it to say something in a certain way. And then I’ll be like, “Wait, I just wrote the email. The email is done.”

RS: I think we have to cut people some slack. There seems to be this odd hack happening in the human mind right now where the time you spent sitting and prompting and coaxing and waiting, it actually wasn’t easier. But I think there’s something in the brain that makes it easier to get into that mode of asking. Most writers would agree that it’s easier to edit a cruddy draft than it is to stare down a blank screen. So I get it, but it might not actually have saved you any time or mental effort in the end.

AD: What a lot of people have is this obsession with shortcuts or like figuring out how to automate something where I’ll spend six hours automating something that would have taken two seconds and I won’t ever have to do again.

RS: Yeah, classic, classic.

AD: So, do you consider yourself a hater? Or what do you consider yourself?

RS: I’m not a hater. Skeptic isn’t even right. I guess I’m often frustrated because for me, the interesting and noteworthy thing about these models seems really different from what I hear other people talking about. The thing that continues to compel me deeply is what they are, and in my estimation, what they are is something radically new on this planet.

They are super complicated computer programs that were not programmed. The scaffolding for them—the trellis—was programmed, obviously, and highly skilled programmers did a lot of work to do that. But what they produce is different. It’s the trellis and there’s no plant. There’s no rose bush. You’re just slamming this system with all this data, and a particular kind of computer program of incredible complexity grows that does these astonishing things.

That’s so interesting to me. All I want to talk about is how that works and what’s happening inside the program. The programs operate inside these high-dimensional spaces—these vectors, these points that don’t just have two or three components but thousands. Physicists have talked about high-dimensional spaces for a long time, and they’ve complained that you can’t imagine them. We know things are happening; the math works incredibly well, but when you try to visualize it, it just kind of breaks.

That to me is fascinating. It seems different from the sort of businessization of just turning this into plain old software and asking how people are going to use it. I’m just not interested in that. So it’s not that I’m a skeptic; I just want to have a different conversation about AI. There are some folks who are engaged in that, including many at the big frontier AI labs, but it’s not what you mostly encounter.

AD: I want to talk about your analog and offline world. Is that move toward more physical stuff a response to AI?

RS: It’s a response to a suite of trends, and it really has to do with the evolution of the internet over the last ten years or so. It’d be easy to say it’s all because algorithmic crud is being shoveled at us by recommendation engines, and a lot of it is that. But there’s also a lot of beautiful and interesting stuff out there—there’s just so much.

I’ve observed my own response to things when I look at them on my phone or browse the internet. I’m a voracious reader; I seek things out and I’m always up for interesting art projects. Yet when I find them on the web, my reaction is often, “Cool. Onto the next thing.”

I’ve observed my own response to things when I look at them on my phone or browse the internet. I’m a voracious reader; I seek things out and I’m always up for interesting art projects. Yet when I find them on the web, my reaction is often, “Cool. Onto the next thing.”

Luckily, I have the counterexample of books and people’s engagement with them. I’ll get an email from somebody saying, “Hey, I read Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, and I really enjoyed it.” That’s incredible because what looms behind that message is the image of a person sitting on an airplane, at home, or in bed with a book, spending somewhere between five and 48 hours immersed in this thing that I made, bringing it to life in their own mind and truly paying attention.

I think about the value of that encounter versus these online encounters. If there was a preexisting trend toward there being just so much stuff, AI only accelerates that. So for my own sake—for my own feeling that work is worthwhile and sustainable—I’ve been on a pretty steady trajectory of making things in the physical world and hoping to get a bit more of people’s time and imagination offline.

AD: How’s that been going, and where do you see it going next for you?

RS: It’s been going great. It’s not only an attentional gambit; it’s also an economic gambit. It’s wild that you can make money online, but when it comes to content and writing or art, the online money math is just absolutely punishing. You could be an aspiring YouTuber and post some really cool creative videos that get 100,000 views, and you’d be saying, “Well, that’s not going to cut it, right?” That’s not a living, which is insane. Flip it around: I’ve been printing these little zines right here in my office on a Riso graph printer. I lay them out and design them on my computer. I’ve been printing them in editions ranging from 500 to 1,000. These aren’t web numbers, but they sell out fast because I have a pretty substantial email list. I sell them for $7 each. You do that math, and you’re like, “Hey, that’s pretty good.” How many YouTube views, Spotify plays, or Substack subscriptions do you need to hit that number?

That’s not to crow about my super profitable empire, but the point is that offline math is so much more appealing and sustainable. It puts you in that realm where, especially for an artist, it should feel so empowering. If you could get a hundred people who are down for everything you do, you can actually begin to build a life out of that. But that’s only possible if you’re talking in real physical-world dollars and not views, plays, and clicks.

It’s not only an attentional gambit; it’s also an economic gambit. It’s wild that you can make money online, but when it comes to content and writing or art, the online money math is just absolutely punishing.

AD: That’s super inspiring. I’m probably close to that with my Substack, but it feels like not enough because it’s internet math.

RS: When you submit to the internet game and say, “I’m going to take a shot at the internet math,” whether you’re successful or not, you sacrifice that frame. The literal framing of what this thing is, what it’s about, and its goals. YouTube really thinks the number of views on a video is important, and therefore, they are important to you whether you like it or not.

The beautiful thing about the physical world is that, if you think of it as an API, it’s an endlessly rich and flexible API. The online stuff is just a little box for you to fill in, whereas the physical world is this completely open canvas. Things can be a certain size, a certain shape, and they can arrive in a certain way. I find it oddly exciting. The technology of the physical world honestly feels more interesting and flexible to me than the relative rigidity of the online world. It’s so odd that in the digital world, this perfectly protean thing could be made to feel so rigid.

I do think one of the formats we’ll see more of is things that are not just rectangles the size of a screen. If you’re making something that is a rectangle about the size of a screen, maybe you haven’t done what’s fully possible. Whether that’s the march of big movies toward IMAX or print products that return to the old newspapers in the ‘60s that were like a bed sheet—that’s cool. You can have a lot of fun with that. I think that’s something for artists and content creators of all kinds to really think about.

AD: Do you personally fear AI taking away anything you do? And for people who do have that fear, what advice would you have for them?

RS: I don’t have a huge fear. That’s not to say it doesn’t cause me any angst. Anybody who has a really firm opinion of what comes next is wrong because a lot of the real, deep assumptions about what writing and media are are suddenly unmoored.

I often have this thought I’ve shared with some publishing people: If we were presently operating under a great novel shortage, then maybe I would be like, “Man, these AI robots sure can write a lot of novels.” That is not the case. There are already way too many very good, very interesting novels and books written by real humans. So the addition of more good or cruddy AI novels really doesn’t change the dynamic equilibrium.

To your question about what people starting out can do, I think there has been a crisis in criticism. I mean that in the most expansive way—not just hardcore criticism, but consideration of art. Think about the first album from some little band down the street from me. Who will write a review of that on the internet? No one. It was always hard to get attention, but I have this sense that a decade ago, there were more people consciously engaged in the work of telling you about new stuff. One reason that has fallen away is that recommendation algorithms have taken that role. So it’s hard to tell people they should spend a lot of time doing that work because it’s even less remunerative than making the art. But I try to do that in my own newsletter. I think it’s something everybody interested in the future of art ought to be doing more of.

The person who’s beginning to write in the age of AI and hoping to one day have readers has to have a vision for how, in five or ten years, there’s going to be a mechanism for people to find the thing they wrote and are proud of. So one of the things you can do today is to help keep those mechanisms of discovery healthy. Otherwise, everybody who wants to make cool stuff and find cool stuff made by other people is going to be in a tough spot.

AD: You’re saying, essentially, elevate the work of others.

RS: Yes, elevate the work of others. We’ve seen this pattern play out in the economy with a real focus on the top winners. There’s cool writing about Taylor Swift, but where does the next Taylor Swift come from? Who’s going to be the first person to respond in a deep and sensitive way to a piece of music posted on Bandcamp by somebody in their bedroom? All it takes is a little bit of attention and consideration. So I do think, in almost moral terms, anybody who aspires to have people engage with their work has got to spend a little time passing that baton of attention around.

AD: I’m embarrassed to admit that I think about doing that all the time, and then immediately I think, “Well, maybe that can be how I monetize,” but I don’t want to do that. But then the other fear is, I’m hustling, you know.

RS: You put your finger on it. The economy has turned all the artists into hustlers. They’re afraid to surrender any of the meager attention they’ve been able to find. When, in fact, it’s like a prisoner’s dilemma game. If everyone was more generous with that attention, the whole ecosystem would be healthier.

AD: If the medium is the message and AI is the medium, what do you think the message is?

RS: This could change, but for now, the message is, “Why not a little bit more normal?” If what you were making was sub-normal, not very good, or if your goals are normal, then that works for you. But if you’re doing anything that would benefit from being not normal, you’re not going to get what you need out of it. The whisper in your ear is, “Couldn’t it just be a little bit more normal?”

AD: Someone else I was interviewing brought this up, saying it seems like the people who need AI the least are the ones who can use it the best because they already have taste. They know what they don’t like about what’s given to them.

RS: Yes, that’s true, and it’s a deep paradox. And everybody else is still kind of like, “Well, I was pretty bad at this before, and now I’m a little less bad. I’m bad in a new and exciting way.”

AD: Now I’m bad in a new way that takes up a lot of time, and nothing really gets done, but it’s fun. So, walk me through ways you are actually using AI.

RS: Some of the uses are so profound and useful. At the same time, it’s shocking to recognize that if these were the primary uses for these tools, they would be a commercial failure because so much money has been poured into them that they can only transform the entire economy.

Here’s a simple thing you can do when traveling to countries where they don’t speak the language. For many years, I gratefully used Google Translate to capture the nuance of what I wanted to say. But it turns out that’s not always what you want. I have a little prompt I copy and paste into Claude or Gemini. The prompt is basically: “I’m going to give you a phrase, and I would like you to translate it into Japanese (or any other language). I would like the tone to be extremely polite. However, I would like it to be as concise as possible because I’d like to say as few words as possible. If the meaning is about 70% correct, that would be fine. Please now show me the translation in Japanese script, in the official romanization, and then finally give me a phonetic pronunciation.”

It works amazingly because you realize that to have something short and simple means you can walk up to the counter and you’re ready to go. The alternative from Google Translate was a paragraph of text to precisely modulate the English meaning. It has actually transformed my travel and my communication.

AD: I love that. Do you have any others?

RS: I think that’s it. The other recipes would be anti-recipes. For years now, since 2016-2017, I’ve been checking in on the writing and editing capabilities for fiction. I did a test recently because the stuff keeps improving, and I can’t just make one judgment and walk away.

I wrote two different prompts. The first was: “Please read the following story draft. Act as an editor. Recommend and think carefully about how it could be improved in ways both large and small. Then please offer three to five suggestions that the writer will then go away and implement.” It did that with incredible fluency.

Then I piped that result into a second prompt that said: “You are a writer revising a draft of the story. You received this bulleted list from your editor. You don’t have to implement all of them, but anything that seems appropriate, please implement that in this draft and then respond with the edited manuscript.”

The edits were good in the sense of being competent and actually reflecting the subject matter and language of the story. You have to concede it’s pretty wild that a computer program would do that. But these were not the edits of an expert who has written a thousand short stories; they were the edits of someone who has read a hundred books about how to write stories. Ultimately, I couldn’t use this thing, and I know from experience I would have gotten at least a few good things from a really good human editor. So that’s where we are with editing with AI at this time.

AD: In a hypothetical world where it does give you really good ideas, what happens then? Do you use them?

RS: That’s a great question. The honest answer is I don’t know.

AD: What do you wish AI could do but fear it never will?

RS: I think it should be able to remain silent. They’re so fluid; they can respond in so many ways. The only thing they cannot do is refuse to respond. I mean, they can refuse, but they do that by saying, “I’m sorry, I would rather not talk.” The only thing that exists is more speech, more text. In our physical world, there is great eloquence to sitting in silence, and an AI, definitionally, can never do that.

The only thing they cannot do is refuse to respond. I mean, they can refuse, but they do that by saying, “I’m sorry, I would rather not talk.” The only thing that exists is more speech, more text. In our physical world, there is great eloquence to sitting in silence, and an AI, definitionally, can never do that.

AD: What question about AI and creativity is not being asked enough?

RS: It’s good to go back to what AI is as a subject. What’s happening in that high-dimensional space? There are people who are pursuing this question vigorously, and most of them are at the frontier labs in the discipline they call mechanistic interpretability. After years of incredibly intense effort, they still mostly don’t know. It is substantially a mystery. So that’s the question: What’s going on in there?

AD: Last question: What do you wish people talked about more instead of AI?

RS: I was going to say money. Questions of money, wealth, and power get laundered through an AI conversation. I wish every time people talked about AI, they also talked about the money—where it’s coming from and where it’s going.