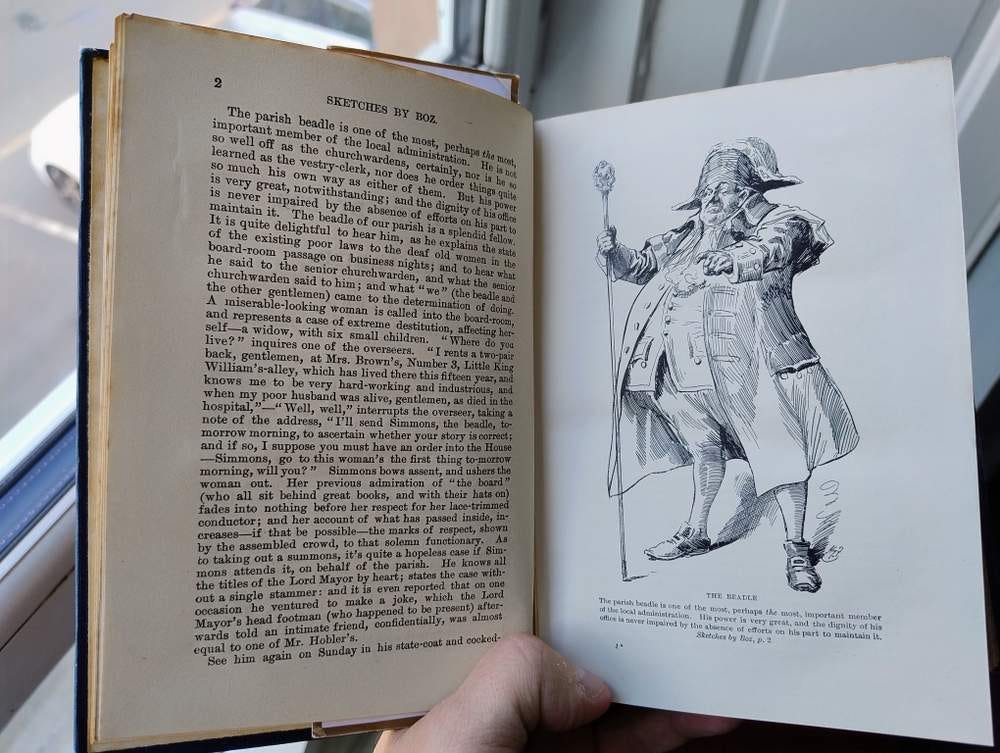

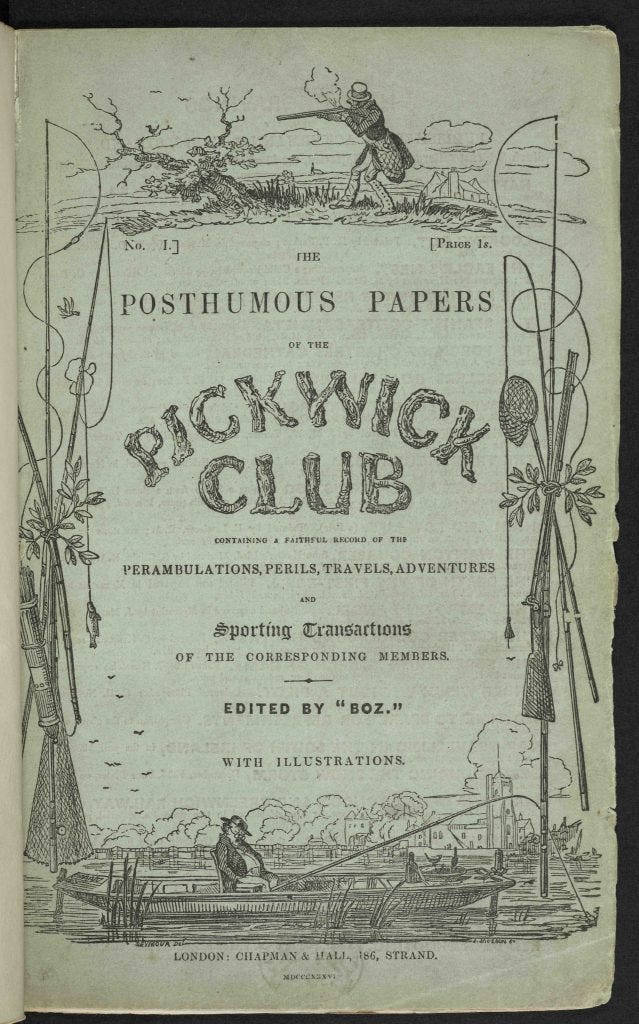

Hello again! Today’s the last day of the end-of-season offer for Everything Is Amazing… …and it’s time to explain what’s coming for paid subscribers in the upcoming season. If I may, I’d like to introduce you to a book that’s very special to me. Every year at this time (it’s my birthday today), I like to sit by a window and read it for a while, to remind myself how ludicrously subjective the term “old” is. The spine crackles as you open it, and the pages have a musty scene that’s so complicated it could only be the product of decades of moving through the world, soaking up the smells of so many different rooms and their furnishings and occupants, until it’s become a piece of 20th-Century olfactory archaeology. (Yes, that term refers to a real branch of research! No, I didn’t know this either.) And its author? It’s the work of an entrepreneurial young journalist writer from London, whose stuff you really should read. Sketches By Boz is a series of 56 portraits of Londoners and their environment, a mixture of the true and fictional, accompanied by beautiful illustrations, and eventually bundled together into…well, this: Boz didn’t have any problems marketing this book: pretty much all the major London newspapers and magazines eagerly agreed to run many of these “sketches” in their pages because they were already wildly popular. (Think of it as a British semi-fictionalised version of Humans Of New York, with a similar level of fame for its time). However, that wasn’t Boz’s master-stroke. Seeing the massive potential for serialized content like this, he’d been working on another title - a wholly fictional story he was eagerly writing his way into. But instead of choosing to publish that as a book, he drew on his journalism experience to release each new segment of the story as a separately printed pamphlet, a ‘column’ printed outside of a newspaper, and sold for the equivalent of the price of a beverage. (A newsletter, I guess, as we now understand it!) This he delivered with the help of a publishing house in 19 monthly editions across nearly two years. Sales went nuts - as did piracy. Bootlegs, ripped-off characters, blatantly unofficial merchandising - basically, everything we’re used to seeing when something’s a big-enough hit. The first instalment shifted an encouraging 1,000 copies. The last sold over 40,000 (these are physical copies, mind, not just emails that cost almost nothing to send, so it was an amazing feat) - and since Boz quickly saw the value of bundling the instalments into a single book at the end, he started his next series with book-writing firmly in mind, while continuing to play on all the strengths of serialization that he’d discovered with the previous story. It was a career-building model. At the age of 25, Boz was a colossal success. That super-successful fiction project was titled “The Posthumous Papers Of The Pickwick Club” - and Boz’s real name is Charles Dickens. The book I have here in my hand is the first in an 18-volume set printed by the Educational Book Company in 1910 - published to celebrate the centennial of the birth of Dickens in 1912. I have the others in storage at my aunt’s house, waiting for the time I make enough of a permanent home for myself that I can give them their own bookcase. I don’t know how many copies of these books were printed - they’re certainly not terribly hard to find online (here’s the full set on eBay for £150) which suggests it was a big, popular print-run. But this particular book? This one is here. It’s spent twice my lifetime travelling who-knows-where to get here, being a tiny corner of 20th-Century history while holding within its pages a major part of the literary legacy of the previous century - and now *I* get to be the one reading it? Pinch me. Aren’t books terrific like that? Not just what’s in books, but the physical objects themselves. Don’t get me wrong, I love all our fancy new e-reader tech to distraction (my Kobo Libra 2 for the win!) but nothing beats reading an old, beautiful book that makes your wrists ache because it’s just so heavy and so impressively real. There are many great newsletters about the joyful acts of reading and writing, including on Substack - go check out Jillian Hess or Simon Haisell if you want proof. But I find myself quietly haunted by something I learned a while back about the power of handwriting in this increasingly digital age - of the vast difference between typing a word and writing it:

What if reading an actual, actual book is somewhat similar? Since books have been around for thousands of years, surely we’ve adapted to respond to them as physical objects as much as to the raw information conveyed within them? Isn’t that worth looking into? But while we’re at it - what is a “book”? Is it a book if words are written on, say, metal plates instead of some kind of paper? (If so, the oldest book is an astounding 2,670 years old!) And how exactly do you make a book? How do you assemble and bind a book together? No, wait - how do you even make paper? (And what exactly constitutes “paper”, while we’re at it?) Why am exactly 54 years old today and I still don’t know the answers to these questions? (What have I even been doing all this time? Explain yourself, man.) Then it occurred to me that where I currently live, there’s a timber processing plant a ten-minute walk away, and a paper-making mill on the horizon, belching white smoke into the Scottish sky all year round. Do they offer tours? Do they offer tours to idiots with newsletters? I intend to find out. This, then, is what’s afoot for paid subscribers in season 8. We’re looking at the physical presence of books in our world, this human-built, plant-based information technology that’s served us so well (and perhaps changed us so profoundly) over the last couple of thousand years that we’ve come to view it with a love bordering on obsessive. A love that can leave us morally outraged when, say, we learn two and a half million “unwanted” romance novels have been turned into a motorway. Scandalous! But I’ll also be looking at research into what paper books do for our minds, and what the rise of electronic reading is doing to our ability to comprehend, to think and to imagine, even while it seems to offer us shiny, trendy new ways of doing all these things. Exactly what experiences and feelings are we trading off here? What’s the science on this? I want to know. (An analogy: you know what I love about paper maps? It’s when you spread them out and lean in and they fill your entire view, including all of your peripheral vision. I liken this to my first experience of trying contact lenses - suddenly the spectacled window I’ve always peered through the world at was gone, and I was suddenly *in* the world in a way I hadn’t been beforehand, which punched the breath out of me…which is why I recently found Dr Susan Barry’s story so affecting.) I reckon there’s a lot to learn here - and if you’re one of EiA’s paid supporters, I’ll be sharing all of it with you as I go, along with the results of my quest for a good night’s sleep, and every other article I’ll be writing behind the paywall. If you want to upgrade, click the button below to get that discount before it runs out. Thank you so much! - Mike |