Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing - a newsletter about science, curiosity and the joys of a good, hard Wow. This newsletter is on a between-seasons break right now. If you’re on the free list, alas, you won’t get anything new from me until mid-November! I’ll only be writing original pieces solely for paid subscribers, including on my quest for a good night’s sleep according to the latest science - and if you like the sound of that, you could join them by clicking below: Today, though, here’s a re-run from a while back (originally here). It concerns the most northernmost part of the still-poorly-mapped ocean floor covering over two-thirds of our planet - the subject of the fourth season of EiA - because it seems there’s something unexpectedly huge and dramatic under the North Pole? To set the scene, let’s chase solid land as far up as it goes. In the middle of 2021, a group of researchers announced they might have found the world’s most northerly island, off the top of Greenland. Perhaps that sounds that sounds a bit non-committal? Yes, commendably so! As good scientists work with hypotheses and theories, they try to remain open to the possibility (however remote) of being proven dead wrong - so it’s a source of ongoing frustration for researchers when their circumspect language is mangled into emphatic certainty, as when the BBC ran this story with the headline “Greenland Island Is World’s Northernmost Island - Scientists.” (As the text of the article itself made clear, those scientists actually weren’t saying that, because they didn’t have conclusive evidence for it yet. Contrast this with Smithsonian Magazine’s “Scientists Discover What May Be The World’s Northernmost Island.” Much better job of it.) The unofficial name for this 30 x 60 metre something-or-other is Qeqertaq Avannarleq, which is Greenlandic for “the northernmost island.” From the air, it looks like - and I apologise, but there’s no avoiding it - a huge dollop of s—. (Call me unromantic, but - imagine you’re out for a walk across a field one bitterly cold winter’s morning, snow and ice crunching deliciously underfoot, and suddenly the way is blocked by a cowpat so substantial you’re wondering if the cow even survived the experience. That’s what I see here.) The researchers ended up there by accident - they were planning to take samples from another candidate for the Earth’s most northernmost piece of land, Oodaaq, discover in 1978 and sitting around 780 metres away. In the words of expedition leader Morten Rasch of the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management:

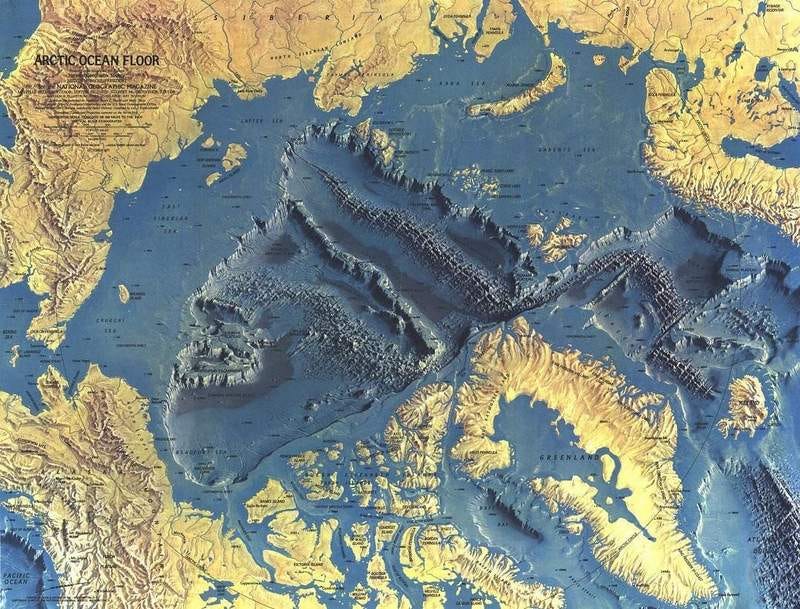

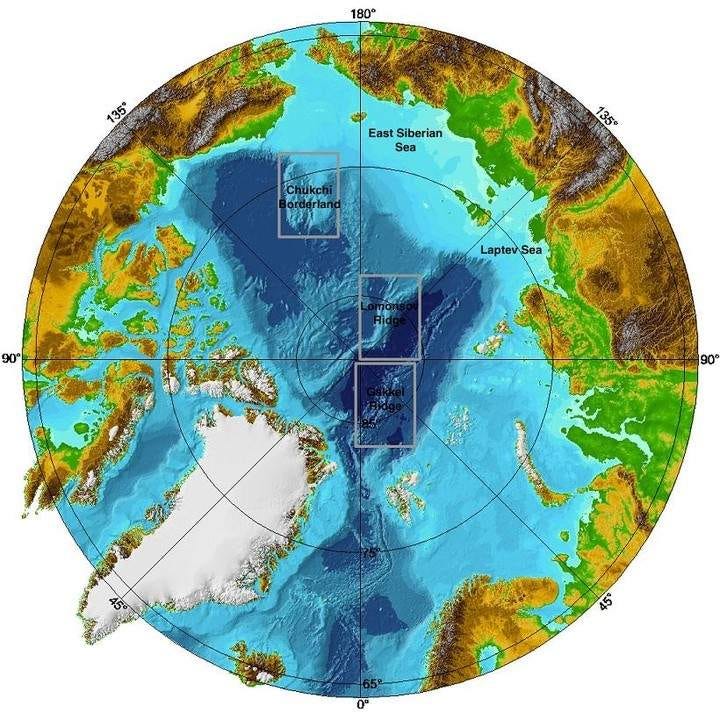

“Island hunters” (nothing to do with the reality TV show) are hobbyists and/or enthusiasts chasing the thrill of being the first to discover new land - so I guess it’s only natural these folk realllly wanted Qeqertaq Avannarleq to be crowned the island at the top of the world. Yet the research team’s caution was warranted. After continuing to investigate the maybe-island - a complicated job, as the sea around it is permanently covered with a layer of ice up to 3 metres thick - in 2023, they found evidence of water flowing underneath, and no sign that Qeqertaq Avannarleq was physically connected to the sea bed by anything except ice. However headache-inducingly imprecise the general definition of an island is (like the human invention we call a continent, it’s riddled with infuriating inconsistencies), what we generally seem to agree upon is that naturally occurring islands are made of land, and “land” isn’t the same thing as “ice”. As a rule, if an island is completely surrounded by water or ice, including underneath it, it’s not an island. Well, except for floating islands! They’re completely different, because, because…uh…? ANYWAY. LET’S MOVE ON, SHALL WE. The researchers now agree that Qeqertaq Avannarleq isn’t an island - it’s just an unusually befouled iceberg. At some point, the immense pressure of the surrounding sea ice pressed a particularly big chunk up against a lovely pile of filth (gravel, soil, mud and other detritus, perhaps depositing by landslides) and then that mucky ice slowly tumbled & bobbed its way to the surface. Not a new thing for this region - these dirty faux-islets appear and disappear all the time - but this time, the hype had clearly got a little too far ahead of the science. It’s a nice example of how some very human aspects of island research - the urge to be the first to a discovery, the compulsion to find the most extreme examples of them - can turn the whole thing into A Grand Adventure, with all the emotion-driven complications that can lead to. (Sometimes this can help grab attention to important research - yet if you’re a professional scientist, you’ll already be aware that grant application hacking by turning it into ‘a good story’ is an ongoing problem that can make a mockery of the whole process.) But here’s something amazing that turned out to be very real - with dramatic consequences for the future of the Arctic as a whole. This splendidly-adorned chap is Mikhail Lomonosov (1711-1765): Russian polymath, scientist, writer - very much the Isaac Newton of his part of the world. Amongst other things, he discovered the law of conservation of mass in chemical reactions, he was the first to announce that Venus has an atmosphere, and he founded some of the key principles of modern geology. There’s a town named after him in the Petrodvortsovy district of Saint Petersburg, a lunar crater with his name, a Martian crater with his name (that’s just greedy) and even an asteroid too… And at some point, as legend has it, he predicted there was something MASSIVE under the Arctic ice. In 1948, a Soviet high-altitude expedition of scientists, pitching a camp on the Arctic ice sea, detected unusually shallow waters stretching northwards of Russia’s New Siberian Islands. Here’s a glorious relief map from the October 1971 edition of National Geographic (in exactly the same style as the ones modelled from Tharp & Heezen’s data, as I previously mentioned here): It clearly shows what the Soviet scientists found (with the vertical height exaggerated for emphasis). Across the whole of the Arctic Sea basin, flanked by mid-oceanic and volcanic ridges on either side, is a whoppingly huge belt of continental crust. How huge? It’s more than 1,800 kilometres (1,100 miles) long, and between 3.3km to 3.7km above the surrounding sea floor, for its whole length, getting to within 400 metres of the surface at its highest point. Imagine a ridge of mountains as high as the Dolomites, with sides almost as steep, stretching from London (UK) to Belgrade (Serbia) or Detroit to Houston - with a flattened top that’s between 60 and 200km wide. On dry land, this would be an absolutely incredible landmark - a standing tidal-wave of rock, dividing whatever continent it ran across. Millions of tourists would come to see it every year. You might have walked along it yourself, or dreamed of owning a little cottage in sight of it. Alas for all that water and ice hiding it from us! It’s now called the Lomonosov Ridge, in honour of the man who guessed its existence 200 years earlier. Now the three countries that border on it - Canada, Denmark (via Greenland) and Russia - are determined to lay claim to it. Here is a map (via the Barents Observer) created by Canada as part of one of its claims to the United Nations: (If you’re wondering what the massive, wholly unlabelled continent at the top is, it’s called “Russia”. Talk about making a statement. 😬) Each country is claiming it’s an extension of their continental shelf, as Martha Henriques explains at BBC Future here:

For decades now, its scientists have been working hard to establish the facts, to take to the United Nations to bolster their formal claims. Extraordinarily, these claims have now become palaeogeological. It’s becoming not about where the ridge is today, but where it was, up to millions of years ago. Imagine laying claim to a place based on its ancient geological history! How messy could THAT get? (Considering my nearest Scottish island Arran started its geological journey near the South Pole around 540 million years ago, as I previously wrote about here, would that mean Australia or New Zealand could lay claim to it? Or the United States, which Arran’s ancient motherland Laurentia turned into? It quickly gets absurd.) All this didn’t stop Russia sending out an icebreaker & two mini-subs in 2007 to plant a rust-proof titanium flag on the seabed, 4,200m (14,000ft) deep: Sergei Balyasnikov of the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Institute issued a statement: “It’s a very important move for Russia to demonstrate its potential in the Arctic... It’s like putting a flag on the Moon.” Other countries? Less than impressed. “This isn’t the 15th Century,” said Canadian Foreign Minister Peter MacKay. “You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say ‘We’re claiming this territory’.” Quite. But of course a worrisome question hangs over all this. Is it going to be yet another flashpoint for future global conflicts, considering how all that inaccessible (protective?) polar ice is already melting? It’s true that new seaways will open up, and the Lomonosov Ridge may contain mineral resources - including millions of barrels of oil - which every country might be more than happy to get their hands on (if that oil exists, which is far from certain). But this is still, & will be for a long time, one of the harshest & therefore most expensive places for humans and their machines to linger on our planet. Expedition costs currently run upwards of $250k every day. International cooperation is still vital for research to get underway in environmental conditions this arduous. And of course Russia’s geopolitical focus is - shall we say - elsewhere right now. All this means time. Time for the science, and time for all the right voices to be invited into the room, as Henriques notes:

For now, the Arctic sea floor remains the site of one of the hidden wonders of the world, with much to reveal to the scientists of the future. Let’s hope it remains that place of mystery and of wonder - and of nations remembering their most productive way forward is when they work together. If you enjoyed having your mind bent by the scale of that story, you may enjoy this piece about what would be the world’s longest international walking trail, tracing the eroded ruins of our planet’s mightiest highlands, if it were ever fully joined together! It’s a piece I wrote just for paid subscribers - and if you wanted to become one, from now until the middle of November when the next season begins, all paid subscriptions to Everything Is Amazing are 10% off. A paid subscription would also give you access to everything new I’m writing over the next 6 weeks, to all paywalled articles in the archive, and give you an optional one-to-one ‘curiosity call’ to motivate you to chase your own nerdiness in a similar way, as I explained here. You’ll also be helping this newsletter exist. It’s completely dependent on reader support - and since 2022 when EiA became my fulltime job, so am I. (Gulp.) You’d be helping me pay my bills and grow this project into what I hope it can become. That’s what you’d be investing in. Click below to sign up with that 10% discount: Thank you so much! Images: Annie Spratt; gcaptain; Stefano Bazzoli; CIA World Fact Book/Wikimedia; Alexander Haffeman; GEBCO. |