The rise of Compaq was fueled by exceptional quality, extreme backward compatibility, strong relationships with retailers, remarkable agility, and lots of bravery. The company began to struggle as low cost clone makers like AST, Dell, and Gateway began taking the market. This forced Compaq to change. Starting in late 1991, the company worked on its supply chains and manufacturing to cut costs resulting in a product line of noticeably lower quality but also tremendously lower cost debuting in 1993. This started with the Compaq Presario which sold over one hundred thousand units in its first sixty days on the market. This may have been due, in part, to a $12 million advertising campaign. More than any other single company, Compaq was responsible for the diminished state of IBM as Compaq became the single largest computer vendor by units shipped by the end of 1994. IBM ended the PS/2 line in July of 1995. In 1996, Compaq made a huge change to how it operated. Up to this point, Compaq had always maintained a large inventory of machines, and they were ready to ship to any dealer who needed product on their shelves. This led to a glut of inventory as sales slowed, and dealers were selling machines at severe discounts. Compaq ceased this practice. The company’s new strategy was more similar to Dell, parts suppliers delivered to Compaq on demand, and Compaq assembled machines as dealers placed orders. This streamlining was managed by software that Compaq had built in-house, and it saved them quite a bit of cheddar. This grew Compaq’s cash reserve from $700 million to around $5 billion. While IBM certainly lost control of the market as Compaq grew, IBM’s PS/2 line was popular in the enterprise desktop space. IBM’s mainframe business was still big, and Sun, SGI, DEC, and others were likewise present in the enterprise market, the workstation market, and the mainframe/server market. The rising Compaq set its sights on these untapped potential sales venues, and on the 23rd of June in 1997, Compaq announced its acquisition of Tandem Computers for $3 billion in stock, and Tandem became a wholly own subsidiary of Compaq. Compaq’s CEO at the time, Eckhard Pfeiffer, stated:

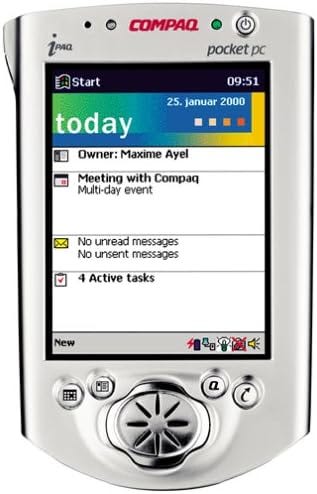

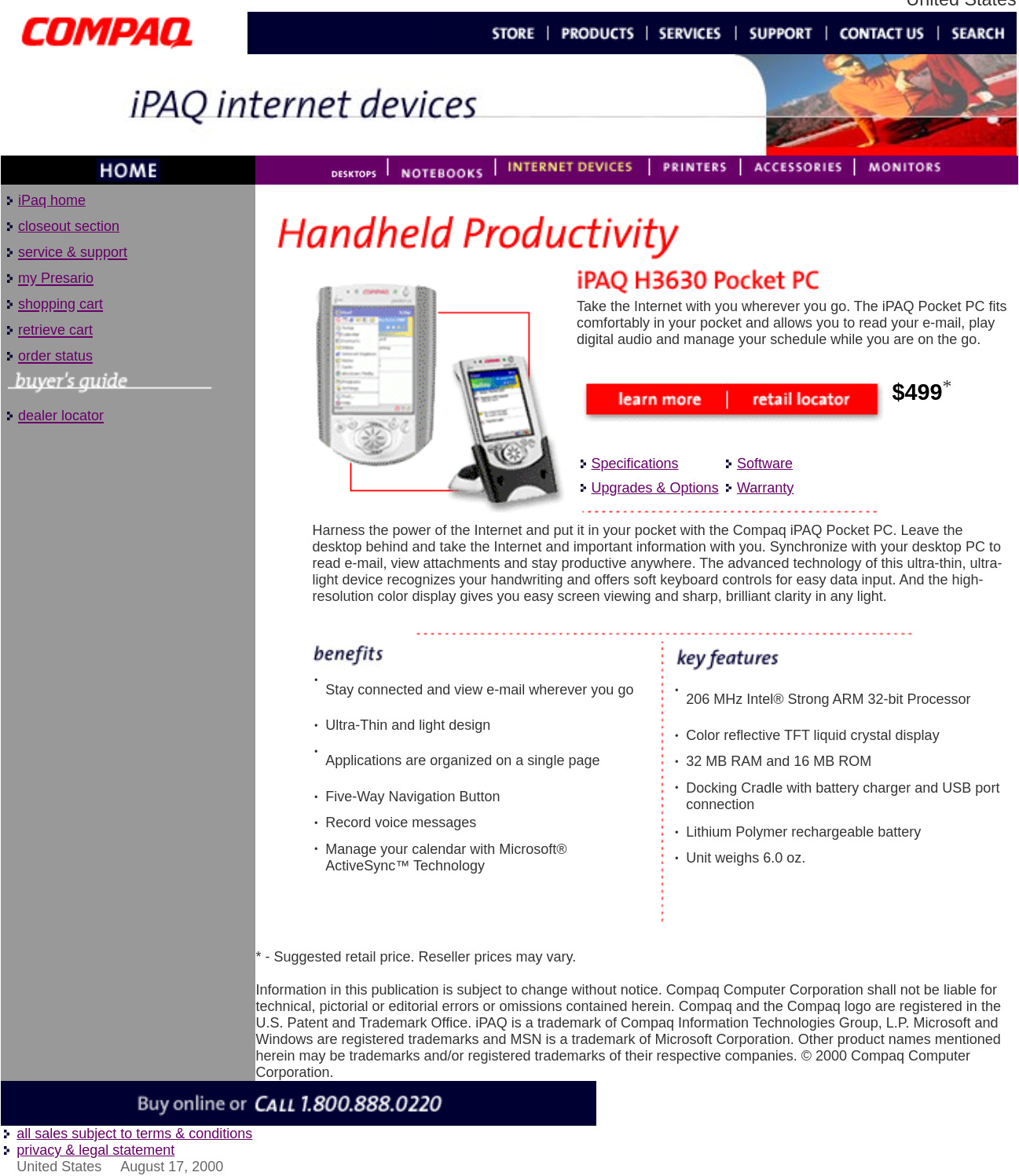

By the time of this acquisition, Compaq had annual revenues exceeding $18 billion, was the largest personal computer manufacturer on Earth by units sold, and to any observer, the company seemed to be an unstoppable force. For the company’s server products, Compaq established a relationship with SCO. About ten percent of Compaq’s ProLiant servers shipped with SCO UnixWare, and the company’s newly acquired NonStop server line ran UnixWare NonStop Clusters. SCO’s software allowed up to six quad-CPU servers to operate as a single clustered system. This technology was then brought to the NonStop Himalaya hardware which offered storage of up to a terabyte and up to sixteen MIPS CPUs. In clusters, Himalaya was able to support four thousand CPUs and three petabytes of storage. On the 26th of January in 1998, Compaq acquired Digital Equipment Corporation for $9.6 billion. With this acquisition, Compaq now had machines in every segment, multiple operating systems, Alpha CPUs, and the AltaVista search engine. In May, Compaq laid off about fifteen thousand employees from Digital and about two thousand from Compaq. These staff reductions were mostly from Digital’s personal computer division as Compaq likely found this division redundant, but there were significant reductions in sales and operations divisions as well. Acquiring DEC was… a terrible idea. Compaq and DEC had very different cultures, different customers, and the timing couldn’t have been worse. Restructuring and integrating the companies following this acquisition took Compaq’s focus off of its hardware and software products. While three different consulting firms were brought in to integrate the companies, Dell began chewing at the PC market. Then, eMachines exploded into the market undercutting everyone. Where once Compaq had been nimble and could quickly pivot to compete anywhere needed, it was now a corporate monstrosity that couldn’t turn its head. The first quarter of 1999 was rough. Earnings for the company missed targets, the company’s stock was down fifty percent from January, and this followed a year of extreme spending. A company that had been cash rich now had over a billion in debt. Pfeiffer was dismissed by Ben Rosen on the 17th of April in 1999. Rosen, Frank Doyle, and Robert Ted Enloe III then took control of the company while they searched for the right person for the job. On the 2nd of June in 2000, Michael Capellas became the President and CEO of Compaq, and he further became chairman of the board on the 28th of September. Handheld computing was becoming popular in the 1990s with the Palm Pilot as the flagship in the segment. Not wanting to lose any ground, Compaq developed and released the iPAQ 3650. The 3650 was a handheld computer that retailed for $499 online with the model 3630, but was often more expensive in a brick and mortar store where it was sold as the 3650. This mighty little machine featured an Intel StrongARM SA-1110 (ARMv5TE) clocked at 206MHz, with 32MB of RAM, a 16MB of ROM, a backlit 240x320 TFT display capable of 4096 colors, an infrared port capable of 115kbps transmission, a microphone, a speaker, and a headphone jack. Physically, the device was 5.11 inches tall by 3.28 inches wide and just over half an inch thick, and it weighed in at about 6.5oz. On the software side of things, the device ran a version of Windows CE 3 called Pocket PC 2000. It shipped with Active Sync, Calendar, Contacts, Inbox, Tasks, Note Taker, Calculator, Internet Explorer, Pocket Word/Excel/Money, Windows Media Player, Solitaire, and some Compaq utilities. Importantly, when in its cradle, the device could sync the Inbox email client with Outlook 2000 (also included with the purchase of the device). Ken Fisher over at Ars Technica loved the hardware, hated the packaging, and mentioned that the flare on the right side held a dedicated hot-key for the voice recorder function and that this was easy to accidentally trigger. An important bit about the iPaq was that it could make use of jackets. These were essentially backs that slipped onto the iPaq and gave various abilities to the device. The most common were PCMCIA and CompactFlash adapters, but there were also CDMA, LAN, WiFi, and even a TV receiver made by Mobilian. The cradle for the device allowed for syncing and charging simultaneously, and the battery would yield about two hours of constant use before needing a charge. As syncing greatly enhanced the usefulness of the device, I imagine that most iPaq owners would have found this acceptable as they synced on and off throughout the day to refresh emails, calendar events, and so on. Importantly for Compaq, the iPaq was a success. It provided a good balance of computing power, battery life, good looks (both screen and device body), and software availability. An essential piece of that software stack was Windows CE. While the original versions of CE were essentially (from the user’s view) Windows 95 with weird screen resolutions, the Pocket PC version in use here was well optimized for the device in question with a UI scheme that matched the input method quite well. The iPaq accounted for about eleven percent of devices shipped by Compaq within its first year on the market. In the server and enterprise, Compaq was messy. The company halted all of Tandem’s work on transitioning from MIPS to Intel Merced, and shifted to working on porting everything to Alpha. Then, in 2001, Compaq ultimately chose to discontinue all investment into the Alpha architecture and began focusing on Intel’s Merced which had been Tandem’s original plan. Naturally, the delays of Merced hurt this effort, and combined with the collapse of the Dot Com bubble, Compaq hurt. Despite the success of Compaq’s iPaq and continued sales of desktop and laptop computers, the company’s profits were shrinking. Capellas stated in April of 2001 that Compaq will “continue to focus on five key improvement initiatives including additional reductions in its structural costs, permanent inventory reductions, aggressive pricing, increased investments in innovation, and broadening its global services.” Ultimately, the fate of Compaq was to fade and fail, or to sell. The race to the bottom in pricing on desktops had led to quality issues. The opening of a web sales front direct to consumer hurt their retailer relationships. The company’s engagement with AMD, Cyrix, and VIA had hurt its relationship with Intel. While Compaq was able to heal its relationship with Microsoft, that relationship wasn’t quite as important for Microsoft as it was for Compaq. The rocketing success of eMachines, Gateway, and Dell had further hurt Compaq. The reversals in direction regarding enterprise hardware kept the company from successfully competing in the more lucrative parts of the computer market. The only new success the company had was handhelds, and those devices were not (at that time) going to move in great enough volume to sustain the company. On the 3rd of September in 2001, Compaq sold to Hewlett-Packard for $24.2 billion. The deal was completed on the 3rd of May in 2002. I have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment. You're currently a free subscriber to Abort Retry Fail. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |