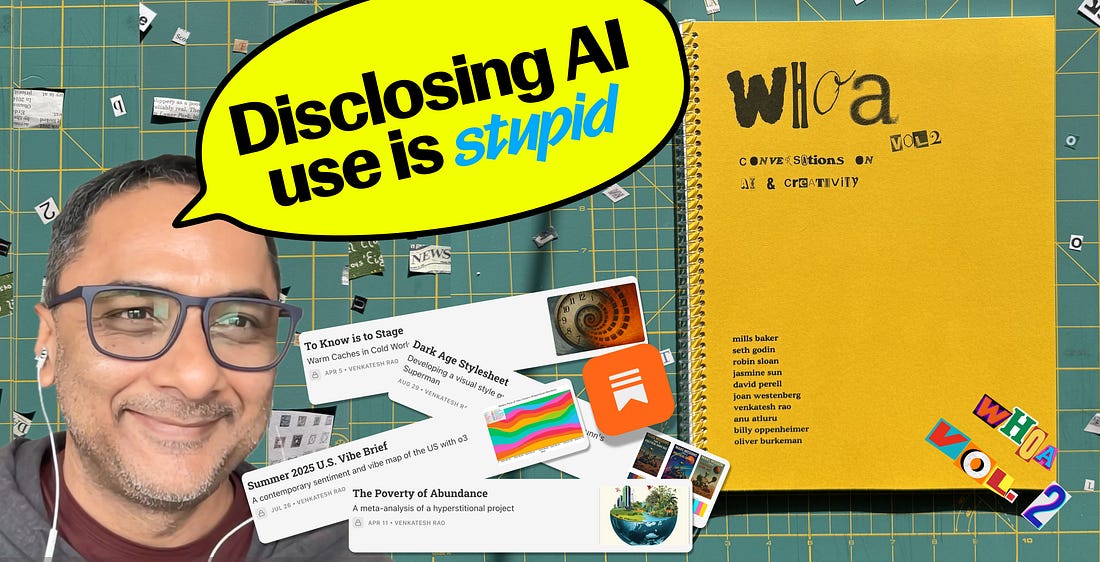

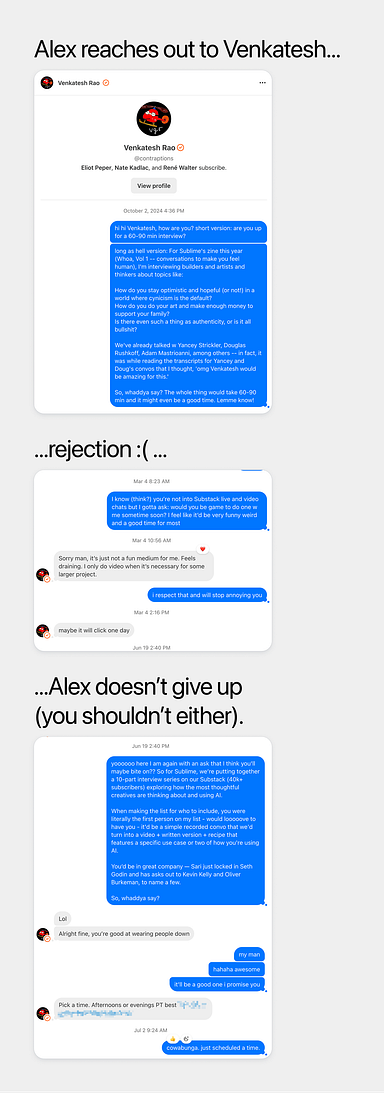

This is the Sublime newsletter, where we share an eclectic assortment of ideas curated in and around the Sublime universe. In case you missed it… we released our annual zine: Whoa, Vol. 2: Conversations on AI and Creativity. We’ll be releasing one conversation here each week. If you’d rather savor instead of scroll + want early access to all ten conversations, including Oliver Burkeman and Anu Atluru, grab the physical + digital zine. ONLY 2 COPIES LEFT!! This series is made possible by Mercury: business banking that more than 200k entrepreneurs use and hands down my favorite tool for running Sublime.Companies are only hiring AIs. You need VC money to scale. This economy is bad for business.If you’ve fallen for any of these oft-repeated assumptions, you need to read Mercury’s data report, The New Economics of Starting Up. They surveyed 1,500 leaders of early-stage companies across topics including funding, AI adoption, hiring, and more.- 79% of companies who’ve adopted AI said they’re hiring more, not less.- Business loans and revenue-based financing were the top outside funding sources for accessing capital.- 87% of founders are more optimistic about their financial future than they were last year.To uncover everything they learned in the report, click here.**Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.A conversation with Venkatesh RaoVenkatesh Rao’s brain is a trip. He rarely does interviews and Alex Dobrenko` has been begging for years (receipts below) so you can thank Alex’s relentless persistence for the gift that is this strange, brilliant, and wildly original conversation. Amongst many other mind-bending ideas, he talks about:

Or listen on Spotify and Apple. (Best if you want to highlight your fave moments with Podcast Magic). The edited transcriptAlex Dobrenko: We’re finally doing this! I asked you a hundred times and you finally caved. Venkatesh Rao: Yeah, my stamina for these things keeps going down every year. I do it for the stuff I’m committed to for work, but beyond that, it does take a toll. AD: What kind of toll? VR: It just leaves me drained. AD: Well, I’ll try not to leave you drained. That’ll be my goal. I’m really excited to talk to you. I feel like you’re one of the voices I’m most curious about, and one that’s very different from most. Maybe that’s a good place to start. How do you feel like your perspective differs from the sort of “normie” AI chatter that’s happening these days? VR: Is there such a thing as “normie” AI chatter? I don’t think there is one. In different corners, different voices get amplified, and it sounds like there’s a single monocultural conversation, but there actually isn’t. Since you and I have interacted on Substack, I think Substack has emerged as an intersection between the older Silicon Valley rationalist corner and what I would call the creative-artistic backlash corner. It’s a very weird pair of worlds colliding. I think the rationalist “less wrong” crowd has peaked and is on its way out; their conversation is increasingly sounding like a QAnon for AI. Even the terms they had a lot of success incepting into the industry itself — like “alignment” — now, seven years in, feel like a cartoon framework. The word still shows up in press releases as part of managing the optics of an AI project. But in actual conversations among serious techies, I no longer hear anyone talking about alignment per se. AD: I find the creative crowd fascinating because I have felt the wrath of that on Substack. I posted a piece that had a line in it written by AI and a person left a comment saying that a specific line moved them so much that it rocked them to their core. That messed with me, because I was like, “Did I just lie to this person? Did I do something wrong?” I then wrote about that, and then there was a bit of a backlash where people were like, “Dude, if you keep using AI, I’m probably not going to read your stuff.” VR: Yeah, I’ve had people do that. I had one long-time reader, and I knew him personally who said, “I can’t in all conscience continue subscribing if you’re going to use AI.” I haven’t had anybody get actually mad at me because I think I’m so blatant about using AI. You can’t be mad if somebody’s that open about it. A lot of people think I segregate my AI writing for “ethical reasons” as in a full disclosure. I think that’s bullshit. That’s not why I do it. I do it because it’s an art form that we’re all still learning, and it’s useful to have it broken out so other people can examine my generated writings and learn from it. I always include the recipe at the bottom. Again, not in the spirit of full disclosure, but more as, “If you’re interested in this game, maybe we can learn from each other by learning each other’s prompting tricks.” When I actually care to engage with somebody talking to me, I’m very careful to push back when they misguidedly compliment me on my strong ethics. I’ve already declared my intention that once this gets mature enough, I’m going to “converge the streams” — like Ghostbusters tells us not to do – and turn it into one big stream. To me, looking ahead at where this is inevitably going, disclosing that you used AI feels as stupid as declaring, “this was typewritten rather than handwritten.” It’s that kind of distinction. And to your point, I think your reaction of guilt and introspection is totally misguided because you’re doing absolutely nothing wrong. You’re doing the equivalent of channeling the accumulated cultural heritage of humanity as captured in training model weights. I like to joke that if you actually look at how human language works, it’s the first LLM. It’s a very poorly compressed, extremely large LLM, but all the intelligence is in language itself. A guy on Substack, Ilan Baronholtz, has been writing about this. I think a very strong technical and philosophical case can be made that all the intelligence is in language itself. Authorship had to be invented. The idea that ideas belong to people and that there’s something like copyright is basically from the 16th century. It belongs in the same era as Montaigne and the idea of the personal essay and writing yourself into a public persona associated with certain texts. Until about 1500, that’s not how we related to text at all. Look at the ancient epics: you might attribute the Greek epics to Homer, or the Mahabharata to Vyasa, but those are only nominal attributions. In reality, these works were syncretic traditions where thousands of people wrote themselves in. In fact, in the 14th century, Ibn Khaldun wrote a lot of early Islamic scholarship, and back then the bias was the other way. You were so unsure and lacked confidence in your own authorship that you would actually falsely attribute it to famous names in the past. You would come up with a legal argument about what the Quran says, but because you were not famous, you would attribute it to some famous cleric 300 years ago. Or even further back, there were Arab philosophers who attributed their own ideas to Aristotle from the Greek tradition. I think after an anomalous 500-year period of falsely identifying a little too individualistically with the things we happen to write down, we’re going back to a culture where we are treating ideas and words and texts as part of a larger linguistic commons that we sometimes channel into specific forms with some additions that are informed by our personal lived experience. That’s all it is. Look at the foundation of the English language. I’m reading The Canterbury Tales right now. Almost all of it is plagiarized. Chaucer stole half the ideas from Boccaccio in the Decameron. Other stories came from as far away as Asia. Others he just made up. That’s a much more natural state of language. So you don’t have anything to apologize for. The people who have something to apologize for are the ones making unreasonable claims on part of our shared common textual heritage. AD: I have a hundred things I want to ask. Why do you think I feel so bad about it? The other part, which I can already see the fallacy of, is that I didn’t work hard enough for it. VR: I’ll treat those separately. The first one is the almost trivially easy one. The idea of authorship as an individual act written in the first-person voice is pretty new. Montaigne didn’t just invent blogging in the 16th century; he actually introduced that mode in general for talking about stuff that was not biographical. Before that, the first-person voice was extremely rare. It was only used for strict biography. But around the time of Montaigne and Dante with the Divine Comedy, the idea of writing texts in the first person that were not purely biographical became a thing. So there’s this notion of attaching first-person voiced authorship that implies a personal relationship contract with the reader, where you’re saying, “I am in some way authentically channeling this set of ideas through my own lived experience.” The lie is not in the text itself, but in the voice posture you adopt in relation to it. If you wrote the same thing in a slightly different voice, the expectations would be different. After five centuries of writing in this way, we’ve come to think that all text implies a particular first-person voice contract. We’ve adopted this weirdly libertarian attitude of possessiveness and property rights to texts, which is historically unprecedented. On the second thing you mentioned. I saw the phrase creative labor float by, and it struck me that’s a phrase I’ve never used in my life. I do not view creative work as labor. It’s not like picking up a shovel and digging into dirt. It’s fun. It’s a privilege to do. Yes, sometimes it’s effortful, but I would not characterize it as labor in the sense of a social contribution. Yes, there are certain narrow categories like if you’re writing legal documents or screenplays for Hollywood maybe there is a case to be made that you should form unions. But in general, the politics of creative work is not the politics of labor. It’s the politics of personal enrichment and nourishment. If you think you’re martyring yourself for that, I have no patience for you. If you actually want to be credited for labor, there’s more important labor work to be done, like taking out the trash and working with the homeless. This is too much fun to want to be credited the same way. The conversation in the creative world is extremely disingenuous about this. They treat very recent legal regimes as moral absolutes. They pretend that just because there’s a 70-year copyright law, something done to violate copyright in that window is somehow deeply morally offensive. But if you make the tenth rehash of a Shakespeare play and turn it into a movie, you’re doing some sort of homage or revering tradition. I think that’s bullshit. You have to be honest about your relationship to our textual heritage and, more generally, to any kind of knowledge heritage. AD: There are a few things that get interwoven that make this so thorny for people. I derive my value from my work, both value as a person and monetarily, and those are things people are very protective of. I think AI scares people because it says, “You don’t have that kind of moat to protect you like you thought you did.”. VR: This is what I think of as the illusion of effort theory of work. Hannah Arendt calls the middle class attitude toward work homo faber, or the maker. You have this theory that you have a certain prowess to bring to the table and you derive psychological value from actually engaging in it. It’s pleasurable. You can get into a kind of creative flow. But I think the big false consciousness of the middle class is conflating that pleasure that you get from effortful flow with value in the broader social milieu or economy. Those are not the same thing. The way this happens is people take it as an absolute that the work you produce has some value and you need to be compensated. And for some mysterious cosmic reason, the value you derive from it from the world at large should be just about enough to sustain your life according to the ethics of a reasonable lifestyle. We tend not to question where this equation comes from. The market has a different logic. What you get in return for your creative effort is two things. One is the satisfaction of just doing the effort itself. That’s one piece, and you should be happy about it. The other part is a function of two things: the supply and demand of the skill and prowess you bring to it, and the other is that you get paid for taking risks. Risk is an independent variable that you have to own. Anytime you’re faced with the prospect of owning the risk of what you’re doing, there can be a very scary reaction from people who are caught in a middle-class false consciousness. AI is extremely similar. The part that’s scary about AI is fundamentally that to actually succeed with AI, you have to take risks. You have to do things you’ve never tried doing before. Slop comes out when a human isn’t taking enough risks. Anytime I’ve enjoyed a piece of LLM-generated content, I’m like, “Shit, this person took risks.” They tried to do things that could potentially fail. One of my own successful experiments was with H.P. Lovecraft. I love his stories, but I don’t think I can write like that. It’s very atmospheric and full of terror and horror. I took one of my favorite stories, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” and plugged it into ChatGPT. I asked, “Can you transpose this entire story to a transhumanist mode? Instead of interbreeding with aliens, it’s about humans interbreeding with robots and technology.” It did a beautiful job. I took that risk, and it turned out to be one of the best generated things I’ve put out. The people who enjoyed it, most of them got back to me because they enjoyed it as a good Lovecraft-style story, not because I wrote it. That was a risk, and I’ve taken several such risks. Some of them have worked, many more have not. But the prospect of having to take risks and looking foolish while working out new modes of working scares people. And it scares them extra because not only are you feeding some of your humanity to another type of human, you’re feeding it to a statistical, inherited, compressed kind of humanity. The LLM is the digested output of millions of humans over hundreds of years. So you are seeding some element of your humanity to this larger collective consciousness, and that’s the threat. The technology is just a medium for conveying that identity threat. My TLDR is you’re not going to enjoy AI until you actually take more risks. AD: Okay, I like that. Maybe this is just belaboring a point, but is the risk to do the H.P. Lovecraft book for robots, or is the risk to do that and not tell anyone that you used AI? VR: I don’t think it should make a difference. The fragments of text I’m stringing together, either with machine help or purely by myself, are still inherited from the same place. I use a cliché or a turn of phrase I picked up unconsciously from reading Charles Dickens 20 years ago, or I pick up a turn of phrase I just saw on Substack. How original am I being, whether I’m assembling it manually or with a machine? If you’re more scared of one scenario than the other, you need to do some introspection about your very relationship with text because they’re both approximately the same level of scary to me. The mechanism is just different. This is why I equated it to being more scared of typewritten text than handwritten text. It truly is that level. This is something that I think avant-garde writers have always been aware of. There’s a wonderful essay by Jonathan Lethem called “The Ecstasy of Influence.” It talks about how all we’re doing is drawing from this vast ocean of shared collective textual consciousness, and we just arbitrarily packetize them into essays and books for certain practical economic purposes. But LLMs increasingly allow us to access information in its natural state. I think we’re not going to be consuming texts directly that much anymore with authorship boundaries. It will be more in the form of oracles that have digested entire corpuses. You could go through our archives and watch 80 YouTube videos to get up to speed on our program, but honestly, once we get this infrastructure better deployed, I’d say just go talk to that oracle. We’ve loaded up the context of the videos. It might point you to particular segments to go listen to, and that’s a much better way. Books, essays, and journal papers are not natural ways to carve reality at the joints. The entire collective consciousness as a body of text does have joints. The natural boundaries are not the boundaries we’ve chopped them up into for being conveniently economically tradable in ways that generate livings for the people who generate those texts. That is an important utilitarian function, but once you take care of that in other ways, like with software and open-source projects, a lot can change. One of the most exciting ideas I’ve seen in the crypto world was the Protocol Guild. It’s a large smart contract that takes contributions from various crypto projects and distributes them to all the people who contribute to the core protocol. This is how you can fund commons stewardship work that would normally be thankless. Now, imagine this kind of logic applying to much larger literary things, like the SCP universe. The novel There Is No Antimemetics Division came out of that community, which has been collectively creating this richly imagined world. It’s kind of sad that the only person who probably made a ton of money off it is the author, QNTM. Now, imagine if you could put the right mix of crypto split-contract infrastructure and AI infrastructure to construct a kind of oracle. That oracle keeps track of the community and maps out the literary universe that’s emerging. It could come up with a qualitative way to assess the importance of the various contributions and distribute the money. AD: Ok, let’s get into how you use it. VR: All my LLM use is basically out-of-the-box ChatGPT. I don’t do any complicated context prompting; I’m very lazy. If I have to put in a really complicated set of configurations, I’d rather just wait six months because if it’s a good recipe, chances are OpenAI will just make it part of the default. My basic recipe for creative work is to start a thread, brainstorm with it, then have it generate an outline, and tweak it. At some point, I’ll be like, “All right, let’s start working this out section by section.” When I’m happy with a section, I lock it down, have it generate markdown, copy and paste it somewhere, and then continue. That’s how I write my AI-generated newsletter issues. 15-20 % of my LLM use is for creative work. The other 40% is basically my own curiosities, which I think are the core of the playful use of LLMs. These are things I’m just into for my own sake. For example, I’m running a book club where we’re reading a lot of literature from the 12th to 16th centuries. It’s not my area of expertise, so when I’m reading about 13th-century Venetian history, it’s nice to dive into an LLM. This can get very playful in a nerdy way. The LEGO-style creative play is more like five-to-twelve-year-old play—very tactile. This more nerdy, studious kind of play feels more like teenager play. When you’re first learning a video game world or getting into the fandom of a large fantasy or science fiction novel, it’s still a very playful mode of engagement, but now you’re nerding out. I would say my creative play with LLMs is basically shitposting, and the chatbot user experience is the easiest one to shitpost with. The little bit I’ve used coding workflows, it’s harder to get in a playful mode because code is much more strongly articulated out of the box. I’m just starting to get playful with other interesting user experiences. One that seems really promising is on Slack. If you’re on a busy corporate Slack, it’s really hard to keep up with 50 channels where a lot of groups are doing work. Slack just introduced a feature where if you click on “Catch up on threads,” it now has an interaction where you pinch to summarize. It works beautifully. You pinch and get a summary of a 50-message thread between six people in a work group that you’re not truly plugged into. Suddenly, you have situational awareness of a workflow that’s going on in the company that you previously didn’t have. It’s bringing a ludic quality to catching up with corporate information. This ties back to my point about the intelligence in the textual output of a corporation. It’s ridiculous to even imagine individual authorship modalities. Imagine trying to read the textual output of a space program; it’s tens of thousands of people working to make a rocket launch happen. There’s no way you could read it like a book. It’s silly to attribute it to individual authors. But I can imagine being on a very busy Slack and using “pinch to summarize” to get an oracular, bird’s-eye view of what’s going on. That’s reality carved at the joints. That’s a much larger textual corpus that doesn’t fit these traditional packetizations. When you carve reality at the joints in the right way, things get more playful because it feels natural. When you feel unplayful, there’s a good chance it’s because you’re putting it in the wrong form factors. AD: What do you mean by “carving reality at the joints”? VR: A clear example: after I quit Twitter, I took my archive of tweets with me. I have a huge pile of really good threads that I’m proud of, and I had a vague idea of making a book out of them. But when I got into the challenge of making an eBook out of my best tweets, it became really hard because so much of the value of amazing Twitter moments is in the banter and the back-and-forth between people. Some of my best threads are six tweets in a row, but somebody came up with a clever response, and I quote-tweeted it and strung it into the original thread. The true reality of the object I’m trying to capture is this conversation with a particular shape. The challenge is: how do you carve that reality at the joints? This is how texts used to be before Gutenberg. People would travel between monasteries and churches to encounter slightly different versions of manuscripts annotated within different schools of thought. It would be like joining 10 Twitter conversations about a book as opposed to just reading the book itself. LLMs will now do this for me. I can just say, “Here’s the link to the first tweet of the thread. Read the thread, read the responses, go as deep as you want, and let me interact with the thread as a kind of entangled hyperobject.” I believe the right way to capture my Twitter archive is as an LLM oracle. It’s like, dump the entire archive into it and have it become an expert on the contours and mappings of my Twitter archive. The LLM will do a better job of representing my headspace in those 15 years than I myself can at this point. AD: Okay, we’ve got five minutes. I want to do our speed round. First question: how would you describe your relationship with AI? VR: Creative partner. AD: What do you wish AI could do but fear it never will? VR: Nothing. I think I’ll die before we figure the answer out to that question. AD: Everyone’s making predictions about AI. Let’s make a prediction about humans. Where do you think humans will be in 10 years? VR: One-third will retreat without really trying. Another third will grudgingly adopt but never get good at it. The final third, a mix of young people and those with the right aptitude, will become AI-native people, and they’ll fundamentally be transhuman in some sense. AD: What question about AI and creativity isn’t being asked enough? VR: I think they’re all being asked, just in different pockets of the internet. AD: What do you wish people talked about more instead of AI? VR: I don’t have a response to that. I’m a very laissez-faire person when it comes to this stuff. Talk about what you want to talk about. That is the signal. AD: Okay, we’ll take it. Thank you, this was awesome. |