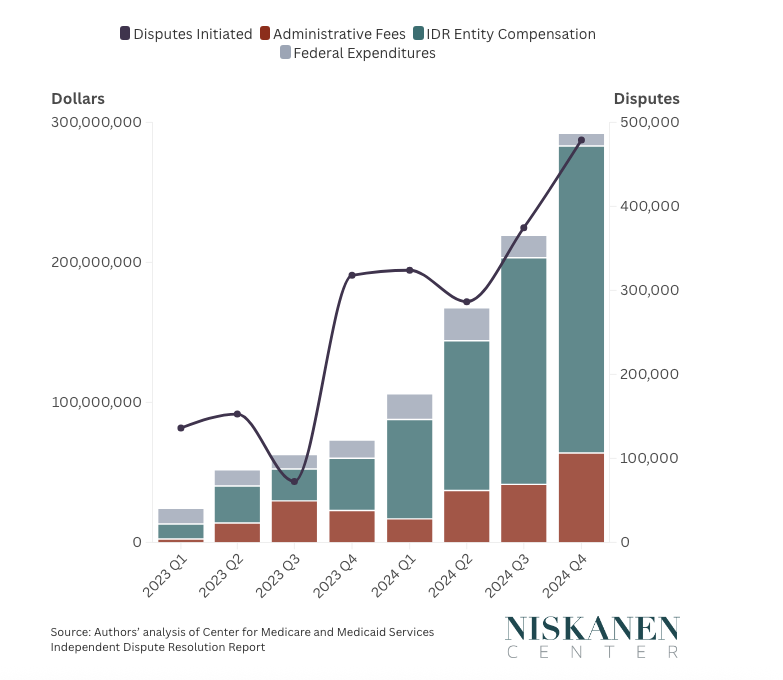

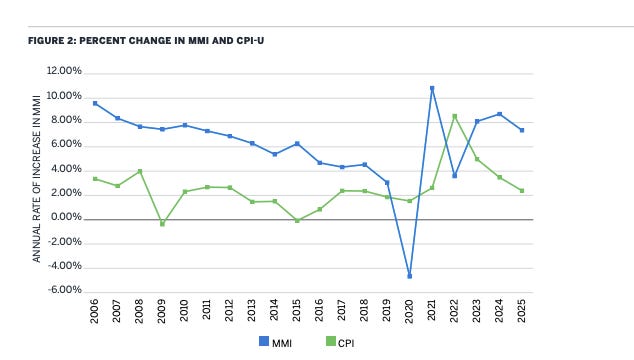

Monopoly Round-Up: Obamacare Is Cooked. What's Next?With big health insurance hikes coming, another health care crisis is here. Where's all the money going? And what comes now? Plus Argentina votes for the Trump bailout, Warner is for sale and more...The monopoly round-up is out. Lots of news, as Argentines voted for Trump’s bailout by picking Javier Milei’s party in a midterm election, newspapers are reporting a comprehensive China deal, and Michael Jordan openly laughed at NASCAR in an antitrust hearing. But first, I want to discuss the news that health care premiums are going to skyrocket next year, after two years of already significant increases. These hikes are throwing both political parties, and the health care system, into turmoil. The ACA marketplaces may collapse, which means the intellectual promise of Obamacare is over, even though Democrats wish it weren’t so. But the Republicans have very little to offer, except on the edges, beyond pretending that all problems with health care started with Obamacare, and offering some snazzy but unimportant programs, like TrumpRx. So the politics of health care is paralyzed, even as the system is falling apart. The reason for this paralysis is simple. Like all of neoliberalism, the last five decades of health care debate was a deal between the right and left to have social goods distributed through increasingly powerful corporations instead of directly through the state. Progressives got something close to universal health insurance “coverage,” while the right got a privatized system with no limits on corporate power and no price transparency. There have been some uncomfortable moments attempting to disrupt this framework, like Medicare for All, but the main thrust of that argument was “for All” rather than the state provisioning care instead of corporations. It was still an access to insurance argument. But that deal in health care is over. We just can’t afford it anymore. Crazy Rich HospitalsThe news kicking off this essay is data coming out about the forthcoming changes in the price of health insurance premiums. And the numbers are jaw-dropping. Here’s the Wall Street Journal, which wrote the cost is now $27,000 for a family plan, according to a KFF study that came out last Wednesday. That’s a jump of 6%. And health care costs were up 7% for the two preceding years. Another major report of health care costs, the Milliman Medical index, indicated with slightly different methodology that the cost for an average family of four in 2025 is $35,000, three times what it was in 2005. There are other indications of much higher costs. For the last three weeks, the government has been in a quasi-shutdown, with Democrats demanding some sort of subsidy for health care premiums, and Republicans refusing. What the Democrats want is to subsidize the health care premiums for a relatively small group, those in the Affordable Care Act marketplaces, which is roughly 20 million people. Failure to do this means that for those buying from the exchanges, prices will go up, from anywhere between 30% to 75% That’s crazy, and what is going to happen is a lot of those people are simply going to forego insurance. And prices are going up for Medicare Advantage plans, a privatized version of Medicare, which is how a majority of Americans over the age of 65 get their care. These plans are cutting benefits and raising prices in 2026. The point is, no matter where you look, prices are going way up. Yet, there’s a big question here. Where’s all this money going? Because at the same time as we have all this new money flooding into the system, rural hospitals are closing, pharmacies are going bankrupt, doctors are being burned out, and generic pharmaceutical firms that make cheap medicine in shortage are closing down factories because it’s just not viable to keep them going. Compared to other similar OECD countries, per capita the U.S. has fewer doctors, fewer nurses, fewer hospital beds, and worse outcomes. So again, this time with feeling: Where’s all this money going!?!? I’ve read a lot of reporting on the drivers of our health care price, and frankly, they don’t make much sense. Reporters, quoting health care wonks, offer a few different explanations. First, Ozempic-style weight loss medicines, the GLP-1 class of drugs, are expensive and widespread. Ok, fine. But a lot of plans who don’t cover those drugs are also skyrocketing. Plus, those drugs might be costly, but they are also bringing down costs with other health benefits, aka the insurer no longer needs to pay for treatment for a heart attack that didn’t happen. Second, there’s Covid-era inflation and labor shortages, which is just kind of hand-waving. And third, people are now seeing the doctor more after Covid, so utilization rates are returning to pre-Covid norms. There is good evidence for that one. But why, if we are returning to previous levels of care, are we not just returning to previous levels of spending? Why is the spending much much higher than it was in 2019? The answer, in miniature, was provided to us by the Chief Cardiologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Yiannis Chatzizisis. On Friday, he excitedly posted on social media an invitation to his new medical facility, at the University of Miami. It’s really worth watching the video to get a sense of the luxury here. This “medical” facility is in fact a gold-plated marble palace, complete with modern architecture, LED art, ornate chandeliers, and a grand piano being played by a professional musician. And note, this facility is owned by a nonprofit, so it’s tax-exempt. The CEO of the UM’s entire health system, Joseph Echevarria, makes $4 million a year, as does the COO, Dipen Parekh. And these wastes of money are not unusual, with nonprofit hospitals building massive campuses and spending money on sports teams. As Stateline reported, “Health care systems and hospital groups have bought naming rights at ballparks and arenas in states such as California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Tennessee.” It’s easy to focus on big corporate villains, and we should, but hospital care is the biggest chunk of health care spending. America spends $1.5 trillion a year on hospitals, versus just $450 billion for pharmaceuticals. And hospital spending grew at 10% in 2023 and 9% in 2024, and is on track for another massive year. This money goes to big city academic hospitals, not the rural ones closing down. The Federal government offers these hospitals competitive advantages over potentially cheaper options, they often get huge tax concessions, and they use their cash to buy up doctor’s practices and slap patients with higher prices. Yet, because they are nonprofits and seen as “charity,” donors give money to these hospitals, which is like donating water to the ocean. When you get your premium increase notification, you will not hear about the urology professor at the University of Miami paid $4 million a year, or the salary paid to the guy playing the piano in a marble medical chateau. You won’t hear about the state-granted monopoly Apexus, which takes a cut of every drug purchased by most hospitals through a special government discount plan called 340b. It will all go into the undefined soup of spending called “health care,” with lots of people fretting and wondering why everything keeps getting more expensive. There are two questions. First, how did we arrive at a place where medical centers spend their money on chandeliers and grand pianos and sports team sponsorships? And second, given the anger towards health care among voters, why isn’t anyone attacking this bloat from a political standpoint? From Health Care to Corporate SludgeAs an “industry,” health care is very odd. Health care debates are focused on this intermediate financial product called health insurance, which isn’t really insurance or care. Health insurance has some features of insurance, but it’s really a quasi-guarantee of access to a set of hospitals and clinicians at a set of prices, with a bunch of financial games like co-insurance, co-pays, and deductibles layered on top. Today, health care is 20% of the economy, and most of the money that goes into this sector is from government programs, including financing for training doctors, drug discovery, and insurance for a little over a third of the public. While the right likes to pretend that it’s a debate between the “free market” and “government,” how we organize health care is a form of industrial policy. For most of American history, medical treatment wasn’t particularly expensive, though it also wasn’t very good. A doctor would hang a shingle, and you could afford his cash payment, or not. Medicine wasn’t that costly. A community would raise some money to erect a building, and boom, there’s a hospital. Modern medicine, with expensive and effective pharmaceuticals, is a mid-20th century phenomenon. Teddy Roosevelt was the first President to try and create a national health insurance program, and over the course of the 20th century, more and more Americans had forms of coverage. Liberals often saw the failure of the U.S. to get universal care as a black mark on America versus other nations, but the truth is that we got pretty close. In the 1960s, Lyndon Johnson and an aggressive Democratic Congress created Medicare (care for the elderly) and Medicaid (care for the poor). Congress offered tax subsidies for employer side health coverage a few decades earlier, as part of the New Deal attempt to create more for workers. The result was astounding. In 1950, 36% of Americans had surgical coverage, by 1965, it was 72%. The poverty rate dropped dramatically because of these programs. It wasn’t just a demand side phenomenon. The government also funded grants to build hospitals, and helped train doctors, fund pharmaceutical research, and create a world-class industry for medical technology. We conquered diseases like polio, invented antibiotics, and forced the widespread disbursal of modern treatments for a whole set of diseases. There were problems, of course, such as the bitter and reactionary doctor’s lobby, the American Medical Association, which was hostile to state intervention to expand care and did not allow for a genuine national industrial policy to build capacity where it was needed. In the 1960s, spending also started increasing rapidly. The original funding mechanism for Medicare incentivized the wild over-building of medical facilities. There were also solutions - states implemented “certificate of need” programs to limit construction. In the 1970s, as with other New Deal programs, neoliberal economists and political organizers began attacking the underlying premise of social insurance. In 1968, a health care economist named Mark Pauly, citing a comment by legendary economist Kenneth Arrow, wrote a paper on the “moral hazard” of health insurance. People who could get treatment without paying additional monies, he argued, would over-consume, driving up costs in inefficient ways. American health care deficiencies were not a result of inequality, the legacy of Jim Crow throughout the South, a weak state, or powerful private interests. It was the grubby patients and greedy caregivers. Pauly’s argument took the economics and health care wonk world by storm, and structured debates going forward. Hayden Rook described what happened, which was the advent of something called managed care. Managed care is a system which put a financial middleman in between a clinician and a patient, to restrict how much patients use the health care system through what was and is known as “utilization management.” That’s also known as rationing. Prior to Pauly’s arguments, insurance covered what doctors said you needed, and the price insurers paid was based on the services the doctor ordered. Pauly’s theory said this was lunacy; doctors would simply over-order, because they were greedy. As Atul Gawande wrote in The New Yorker in 2009 to set the stage for Obamacare, “The most expensive piece of medical equipment, as the saying goes, is a doctor’s pen.” Someone needed to do the rationing, but it couldn’t be the state, since the right would scream bloody murder. But conservatives could allow rationing as long as it was done by a banker, or firms who came into existence like United Health Care. So managed care, which is how commercial insurance, and Medicare Advantage, ACA exchanges, and many state Medicaid programs function, was embraced by both the right under Reagan and Bush, and the left under Clinton and Obama. At the same time, the neoliberal revolution in economics and law was in full swing, and both the right and left saw virtues in consolidated corporate power. In the 1970s, Robert Bork pushed the idea that mergers were good, that large corporations were big because they were efficient. In addition, he argued price discrimination was virtuous, because it allowed more efficient and progressive allocation of output, higher prices against the rich and lower prices for the poor. The left, in the form of men like John Kenneth Galbraith, saw centralization as virtuous, if not by the state, then by large corporations. So the two key features of our health care system were as follows. First was banker-organized rationing known as “managed care.” And the second was the rise of vertically integrated giants across every part of the industry, from drug distribution to insurance to hospitals. It was these features, and not the lack of universality, that distinguished U.S. health care from every other nation. Everywhere else, you could ask for the price of medication or service. In America, that price would be, “it depends if you have market power.” The lack of any consistent pricing is the key feature in U.S. health care, in everything from drug distribution and reimbursement to hospital billing to medical supply procurement. Despite the bitter fights over health care during the Bill Clinton era, the advent of drug benefits for seniors under Bush and Medicare Advantage, and the ACA during Obama’s Presidency, underpinning our health care system was a consensus that corporate power was good. Both sides adopted the ideological goal of eliminating the power of the clinician and the patient, and to move that power to middlemen, who could often control the situation through various forms of pricing choices, like prior authorization or hidden rebates. Fear and Loathing at the HospitalThe result of this consensus has been two things. First, more people have health insurance, at 92% of the population. Yay! Also, GoFundMe’s, and copays, coinsurance, deductibles, and prior authorization are all common. Moreover, insurance firms now own pharmacy benefit managers, health tech, payment systems, banks, doctor’s practices, and everything in between. So the value of insurance is increasingly questionable. It’s supposed to make things easier, but it’s so complex now, some companies offer their employees an extra perk of someone to help them navigate their insurance. Second, there’s a nightmare of bureaucracy. Every time there’s a problem with health care, the ideological response is not to simplify the system by making pricing transparent and standardized, but to add another middleman, another quality control measurement that doesn’t help anything, or another mechanism to fight about pricing. I noted this when I discussed “corporate sludge” last week, showing a monopoly in unnecessary hospital quality surveys mandated by the government, or billing codes that the American Medical Association has a copyright on, or electronic record keeping systems, or HIPAA-compliant note-taking software. Or just big billing departments fighting with other big billing departments, a Spy vs Spy of health care nonsense. Mommy, Where Do Middlemen Come From?Take, for instance, a bill passed in 2020 to address the problem of patients getting billed when a doctor in an in-network hospital was “out of network.” This was known as “surprise billing.” In 2020, Congress passed a law called the No Surprises Act. The idea here is that a patient shouldn’t have to deal with a crazy high bill when they were insured. Well, the gnarly problem here is price. If an insurer has to pay for a procedure, and a provider bills for that procedure, how do they come to an arrangement for what that price is? The whole point of putting together a network for patients to use is that the prices were negotiated beforehand. But when a patient is seeing someone out of network, there is no pre-set price. There’s a nifty elegant solution to this problem. Medicare has a list of prices for all treatments. Congress could have just said, “well you pay at the Medicare rate.” That, however, is against the framework that we organize our system around - pricing must be controlled by the middlemen, and not the public. So private equity-owned clinical practices lobbied to set up… another middleman, in this case an arbitration process. And a friendly neoliberal Democrat, Richie Neal, obliged, (after smearing a left-wing primary opponent with false allegations of sexual improprieties.) As a result, private equity-owned providers are demanding higher and higher rates, and they tend to win arbitration disputes. But in addition, there’s now a set of arbitration firms, certified by the government, who have earned $1 billion charging fees to award money to PE, and their revenue is going up fastest of all. In other words, there’s now a $400 to $800 fee just for the privilege of paying more money to a private equity firm! Here’s a chart from the Niskanen Center. There’s also a ton of compliance cost around hospitals and providers and insurers to manage it all. So most of this corporate sludge doesn’t show up as profit. One way to think about it is that some private equity guy who owns doctor’s practices is wasting $1000 to steal $100. What do these middlemen look like? Well, in researching this essay I actually got an answer to a different question I’ve always had. We all know what doctors and nurses do. But I’ve noticed that there seem to be a lot random consulting firms in health care, and I couldn’t figure out what they actually do. Here’s an example. It turns out this firm is certified for dispute resolution in this new No Surprises Act process. There are hundreds of these kinds of middlemen in every nook and cranny of the system, with hundreds of thousands of well-meaning earnest people with graduate degrees who earn good salaries staffing these firms. But it’s all sludge. Instead of trying to put power in the hands of clinicians and patients, and setting up a financing mechanism to do that, we’ve tried to warp the behavior of clinicians and patients around the needs of financiers. It’s crazy. After ObamacareSince 2008, the politics of health care have been dominated by Obamacare, which is just the latest iteration of managed care. But that’s about to end, because of the increases in price we’re seeing. Talking about “Obamacare” is impossible, because it’s a complicated law that had a lot of different effects on an already complicated system. But when people discuss Obamacare in a political sense, what they mean is whether a system of corporatized middlemen managing care on a universal basis is good. It’s the price hikes that are going to end the pretense that the ACA was a useful path for the U.S. The odd thing is that for the last 20 years, health care inflation, while high, was coming down. A lot of health policy wonks thought the ACA had something to do with reducing the health inflation rate, but the slowing started in 2005, and Obamacare wasn’t passed until 2010, so that’s impossible. But something during Covid kicked up health care inflation again. Here’s a Milliman chart of consumer price index against the inflation rate for health costs. You can see that, as with most other sectors of the U.S. economy, it went up dramatically in the post-Covid era. (And no, it’s not Covid, unless Covid also caused the price of food to skyrocket in 2025.) With such rapid increases in price for health insurance, healthier people are simply going to go without insurance. Since it’ll be the healthier people who drop insurance, and those people cross-subsidize sicker people, pricing will become so expensive that ultimately a good chunk of our insurance pools will fall apart in a “death spiral.” On a political level, no one has a plan to lower price. No one is even thinking about how to attack prices broadly. But it’s not actually hard, conceptually, to get at the problem. The basics of how to fix health care are simple. Make all prices in health care standardized and transparent, and try and get rid of the power of all middlemen who don’t deliver care or directly produce medicine. Most mergers in health care happen to gain an advantage on pricing; if you just standardize pricing, the incentive to consolidate disappears. But to turn this dynamic into a political argument, Democrats are going to have to drop the pretenses that spending more is good, and that the problem is access to insurance. And Republicans are going to have to drop the pretense that there’s a private sector in health care. Whoever is able to turn health care into industrial policy will win this debate. Neither party is close. That said, we know eliminating corporate bloat works; in July, I did a story about what happened when Ohio eliminated CVS Caremark and UnitedHealth, from running its drug benefit system for Medicaid. It turns out, the state saved $140 million over two years, even as dispensing fees to pharmacies increased by 1200% on average, and the program got better, with patients able to access 99% of pharmacies. Corporate waste is the main problem in health care. Other states have also done something like this, with similar success. Abroad, the Japanese run a high quality cheap system. They do not have Medicare for all, there are lots of health insurers. But their government has a list of all treatments with a price next to each treatment. That’s the price. There’s no billing department to fight with other billing departments, there are no quality surveys to give bonus payments to hospitals, no random arbitration firms over price. The price is the price. It’s not like the U.S., where the same procedure or drug could have thousands of different permutations, depending on the insurer, hospital system, physician, and so forth. We could do what Japan does - Medicare has a price list. Just do Medicare prices for all, as Phil Longman keeps suggesting. Getting rid of corporate power in medicine works. It took forty years to build the system we’re in, and most of our policy thinkers are captured by the complexity of the system and the unbelievably stupid obsession with middlemen. But popular rage is now at a boiling point. And saying things like “health care is a human right” or “everyone should have access to health care” isn’t going to cut it. Most Americans have health insurance. It’s just expensive and bad. It’s time to wake up to that. And now, the rest of the round-up. Lots of important stuff, such as the outlines of a major deal between the U.S. and China, automakers turning against big tech, rents declining as rent-fixing by RealPage goes away, the Writer’s Guild opposing the Paramount combining with Warner Bros/Discovery as streaming service prices continue to increase, and the NFL signing another monopoly deal with Electronic Arts, ensuring football video gaming continues to remain boring. All that and much more, after the paywall…... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |