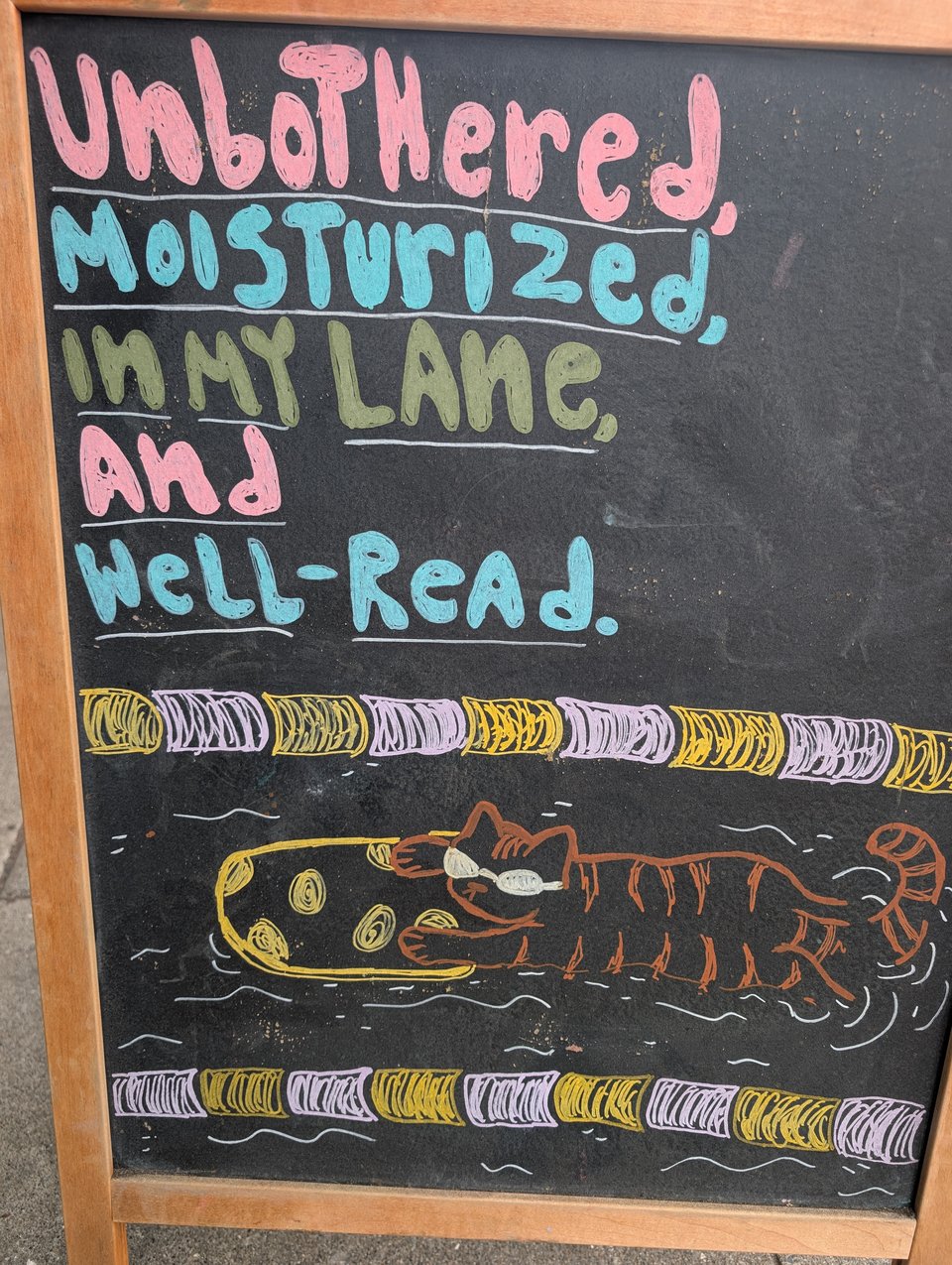

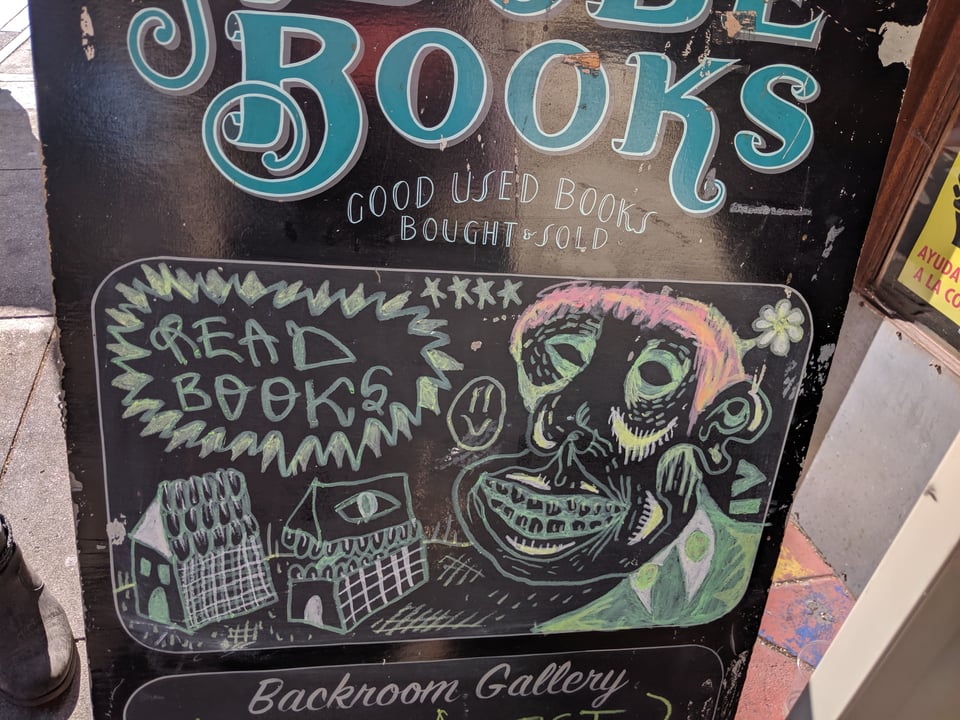

Before we dive into newsletter-town, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that my novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster makes a fantastic holiday gift for your loved ones. Especially your parents or your adult children — it’s a book about learning to understand your mother as a full, complex person. And a mother and daughter working through some tough issues together. I’ve heard from a bunch of folks who’ve gotten it for close family members, and it’s led to some good conversations. As always, get it from Green Apple and I’ll sign, personalize and doodle in it.

Also, I’m coming to the East Coast!

On Nov. 10, I’ll be at the Franklin Park Reading Series in Brooklyn.

On Nov. 17 I’ll be at Parentheses Books in Harrisonburg, Virginia.

On Nov. 19 I’ll be doing an event hosted by Little District Books in Washington, D.C., at As You Are.

On Nov. 20 I’ll be at George Mason University for the Trans Day of Literature with Andrew Joseph White and Dominique Dickey. And I’ll be receiving the Arthur C. Clarke Award for imagination in service to society that evening.

And then I’ll be at the Miami Book Fair!

Please come say hi — the way things are going, this might be my last visit to the East Coast for a long while.

How to avoid a writing pitfall: the weak epiphany

I hate when I'm reading a novel and something happens toward the very end that retroactively ruins the whole book for me.

If a book is going to shit the bed, I’d way rather this happen on page 30 than page 300. That way, I don't waste as much time reading something that I'm ultimately going to DNF. Because I absolutely will toss a book aside if it lets me down, even if the end is very much in sight.

Sometimes this last-minute letdown can be a plot twist that makes no sense. Or a shocking turn of events that moves everything into position for the final climax with the creek of rusty gears and the squeak of overworked pulleys. But to my mind, the worst offender of all is a personal epiphany that feels unearned — or worse, feels so banal that it lays bare how thinly-drawn a major character has been this entire time.

This happened the other day. I was reading a novel that came out ages ago, and the main character had a moment of clarity about what she’d been doing wrong for the past few hundred pages. I felt so betrayed, I actually let out an aggravated snort that made my cat leap off my lap in startlement. The problems here were two-fold.

First, it was something the protagonist could have realized on page 10, because the book had been telegraphing it aggressively since the very first chapter.

Secondly, it just felt too freaking obvious. After following a messy character for an entire book, I watched the protagonist finally grasp that she had been a disaster this whole time. And also to come up with some incredibly surface level reasons for her behavior.

Again, I love it when a character has a moment of clarity towards the end of the book that informs their actions in the final pages. I just need it to be to feel grounded and a little surprising, and to make me feel like I haven’t been wasting my time following this character for an entire book.

In a sense, my issues with weak final epiphanies are a microcosm of my issues with weak endings overall. A good ending lets you know why this had to be a novel rather than a short story (or an inspirational poem on the back of a cereal box). And whatever realizations the main character has are a big part of that.

One of my big maxims in the last few years is to skip ahead whenever you can. That is, I’ve found over and over again in my own writing that if I was planning for my protagonist to discover some piece of plot-related information toward the end of the book, sometimes it’s way more interesting if they make that discovery closer to the start. Then you get to see more of what comes out of that, and it opens up more possibilities for other discoveries at the end of the book.

All too often, I found myself slow-walking a lot of plot developments because the main character isn't supposed to figure out some secret until much later — and when I change things up and have the main character figure things out much sooner, suddenly a whole lot of other plot points that come open to me.

And I feel like the same thing might apply with emotional discoveries as with plot info. If you know a character is going to realize something about themselves on the cusp of your final act, maybe experiment with giving them that moment of self-awareness at the start of the adventure, and see what that leads them to do.

I like self-aware characters, and characters who overthink everything. I also do enjoy oblivious characters who can't what’s right in front of their face — but my usual temptation is to laugh at these clueless jerks a bit. Or to see them as kinda sad and tragic.

In any case, I want to propose a rule of thumb: if something is obvious to the author about a character at the start of the writing process, then it should probably be just as obvious to other characters on the page. And even if the character is unaware of their own issues, other people might take the time to explain.

Which brings me to the other sin that this stale epiphany felt like it was committing: it was just too obvious and two surface level. It relied on reminding us of information that the book had spoon fed us over and over, and it provided no deeper insight into this character and her motivations.

Hence me yeeting the book with only about 20 pages left to go.

I think moving the moment of clarity much earlier in the book would have solved some of this deficit, but definitely not all. This revelation also needed to be deeper and more, well, revelatory.

I'm obsessing over this partly because I've had a similar problem in my writing, including very recently. I've tried to build over the course of an entire novel to a realization that I later realized was just too basic. In fact, in one project I'm currently trying to revise, I feel like this structure committed my main character to being both too surface-level and too unwilling to learn from repeated disasters. It kept my protagonist from growing and changing in a satisfying way over the course of the book because she was waiting to learn something that she could have read in a mediocre self-help book. (Ooof.)

The thing is, I have read novels where the main characters come to a realization that, in retrospect, feels like it should have been obvious. But because the authors did such a masterful job of immersing me in those characters’ points of view, I somehow missed the obvious right alongside them. I think of The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer, in which a whole group of protagonists come to understand that they have behaved horribly at the end of the book — and Wolitzer weaves her story together so skillfully that I really did let out a yelp of surprise when I got there.

When I think about good moments of self discovery on the part of my own characters, it's always come out of a slow immersive process in getting deeper into a character's point of view and emotions. Agonizingly slow, in fact. I've never known what these epiphanies were until I got to them, because I had to go through the journey with the characters in order to understand whatever it is they're going to understand.

I've come away feeling as though if I am able to put an epiphany in my rough outline at the start of writing, it's too basic — and I'll need to come up with something else when I get there.

This makes me a much slower writer than I used to be, which can be a bit frustrating. I often have to write a particular scene or chapter a bunch of times before the characters "feel" right. I have to keep reminding myself to track my characters' inner monologues from scene to scene, so I can follow how their preoccupations are shifting over time.

The result isn't necessarily that my characters gain insights that are astonishingly deep or clever. In fact, I often find that I still end up with epiphanies that are fairly basic, but which come out of legit blind spots in my characters. And I try to make my characters complex enough that these moments don’t feel like they’re summing up the characters’ totality.

For example, in Lessons in Magic and Disaster, Jamie comes to understand that while she's been trying to help her mom get over the death of her wife, Jamie herself has not fully dealt with her own grief over losing her other mother.

This felt like it worked, because A) It's not load-bearing — nothing in the novel’s resolution depends on this insight. B) It felt honest and real, and had not been obvious to me, as the author, until this point in the book. C) This isn't the only new idea that Jamie grasps around this point in the book, and she's got plenty of other issues and emotional minefields to cope with.

That's what makes this tricky — I often adore characters who are missing something fundamental about themselves or their situation. It makes for interesting stories when a character can't admit or isn't aware of their own flaws. But it really helps if a character is fleshed out enough in other ways that they're not just a flaw with a splash of personality.

So I guess if I have to boil this down to an easily digestible piece of writing advice, I'd say that if an epiphany can happen earlier in the book, it should. And the best book-ending epiphanies come out of spending a lot of time with a character and really inhabiting their point of view, because you can't know what they're not seeing until you have a strong sense of what it is they do see.

This was issue #220 of Happy Dancing. You can subscribe, unsubscribe, or view this email online.

Powered by Buttondown, the easiest way to start and grow your newsletter.