|

In 1971 conceptual art dealer Seth Siegelaub and lawyer Robert Projansky collaborated to create a new contract for the purchase of visual art. Called “The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement,” it was, its authors wrote, “designed to remedy some generally acknowledged inequities in the art world, particularly artists’ lack of control over the use of their work and participation in its economics after they no longer own it.” The contract sets a specific array of provisions to do this. (Read the full contract here.) The key rights granted to artists from this: - The right to 15% of any increase in value if the work is resold

- The right to the record of who owns the work

- The right to borrow the work and exhibit it every five years

- Reproduction rights to the work

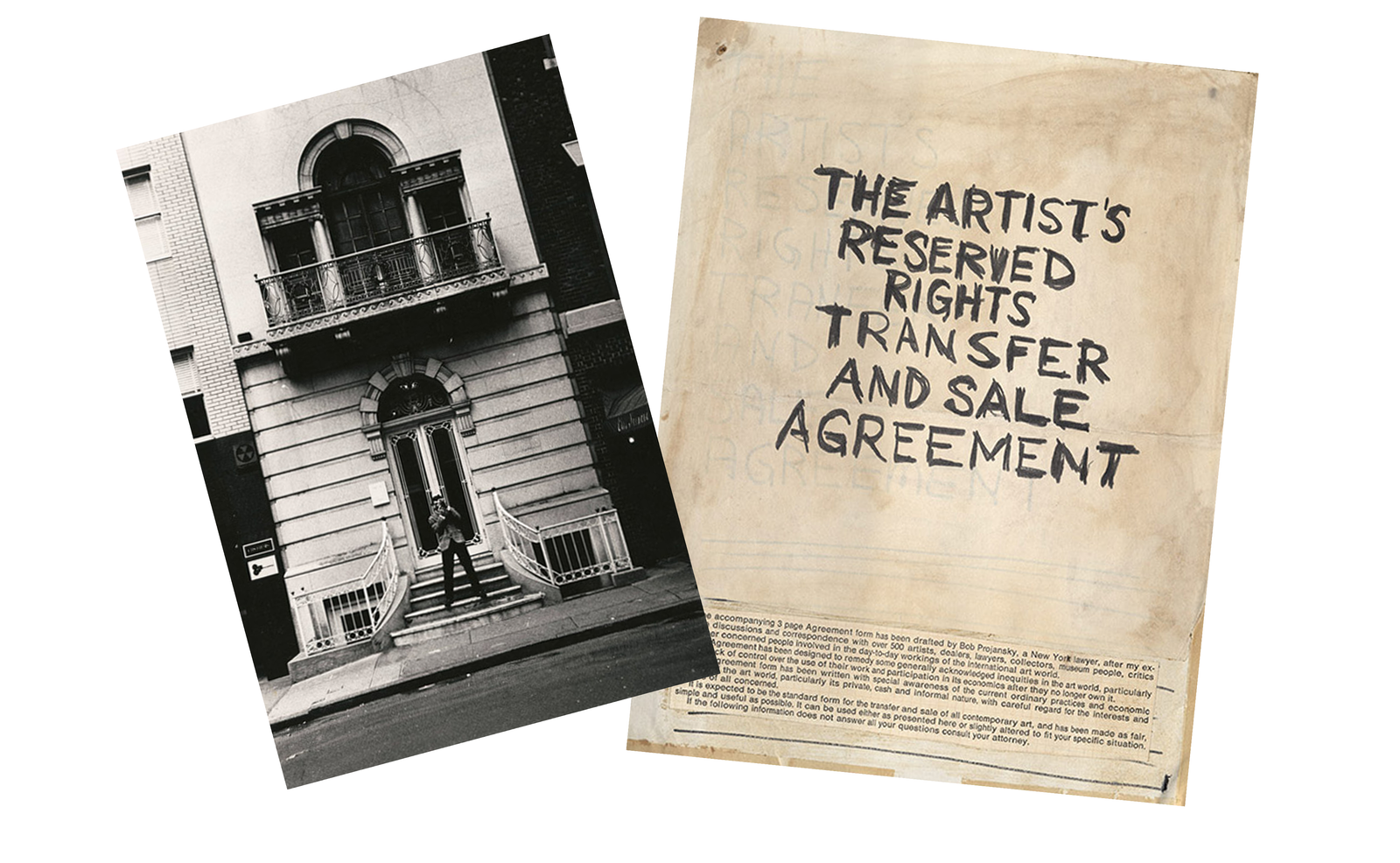

The agreement allows the artist to continue to have an active economic and creative relationship with their own output. When "The Artist's Contract," as it became colloquially known, was first announced, it was international news and widely shared. It was printed in art magazines, where people were encouraged to photocopy it to use with their own work. The contract has been used for many art sales in the years since, however it did not redefine how art is sold the way its authors initially hoped.  Mock-up draft of the Artist's Contract in English Photograph of Seth Siegelaub by Robert Barry How A-Corps echo thisWe've been thinking about the Artist Contract with our work on A-Corps. The challenges both projects attempt to address are largely the same, as is the direction of their proposed solution. But whereas the Artist Contract focuses on each individual art transaction, A-Corps reconsider the underlying system. The most significant financial innovations for creative people in recent decades are updated forms of patronage (crowdfunding), salaries (subscriptions), and debt (cash advances). Meanwhile the core structures of capitalism have greatly expanded, but not for creative people: most notably collective ownership, capital investment, and resource pooling. Those structures have helped turn creative output into capital — for somebody else. The recent boom of hedge funds buying song catalogs for hundreds of millions of dollars is a perfect example. Once hedge funds own these creative assets, they become financialized on their balance sheets and used as collateral to generate more wealth. When those same songs are held by the artists themselves, they don't. They're royalties — a form of income — rather than equity. It’s the same for visual artists. A painting that sells for millions at auction creates enormous value for collectors, brokers, and institutions. Yet the artist rarely participates beyond the initial sale. The artist is a supplier of raw material that's transformed by others into capital goods in which the artist does not participate. Like cotton picked, sold, and spun elsewhere into garments of enormous profit, creative labor remains under-valued because the ongoing structure of ownership excludes them by design. Artists and creative people provide the material needed to make creative industries thrive, but they're not invited to economically participate the same way others are. While this results in moral questions about where value created is distributed, moral solutions are unlikely to provide a path forward. The issues are structural. What A-Corps doThe Artist Contract uses the sale of each individual piece as an opportunity to define a new economic paradigm. A-Corps seek to achieve this by giving legal structures for artists the same capabilities of larger economic players — that artists do not currently have. The A-Corp does this by making collective ownership and fractional shares a core capability of artist-owned enterprises. As drafted, A-Corps will be entities with the ability to distribute and sell ownership to collaborators and investors similar to how startups and other companies can. (Existing securities and tax laws will still apply.) The structure also opens the door to transactions where custody and majority ownership of a work can be transferred, while a partial stake stays with the artist and their A-Corp, allowing them to participate in ongoing upside should it occur. Much like the Artist Contract was designed to do. New legal foundations create new outcomesThe Artist Contract is an inspiring, forward-thinking innovation that proposes a different way of thinking about art ownership that remains sadly relevant today. However it also relies on two parties agreeing to this specific contract without much teeth for enforcement, while hoping its wider spread will create industry acceptance and new norms. The A-Corp, in contrast, seeks to create a universal foundation that establishes basic economic and ownership principles similar to other businesses, while also being designed to account for the unique properties of creative labor. It seeks to create a shared base structure that embeds creative power, creative rights, and economic autonomy into the foundations of every person’s creative practice (if they want it). The issues that prompted artists, dealers, and lawyers to reimagine art ownership in 1971 are still with us. But they’re not laws of nature. They’re defaults set by prior market participants. Defaults can change. The best outcome is both approaches working together: fair contracts that empower artists at the work level, and A-Corps that provide a durable economic and legal foundation at the core.

|