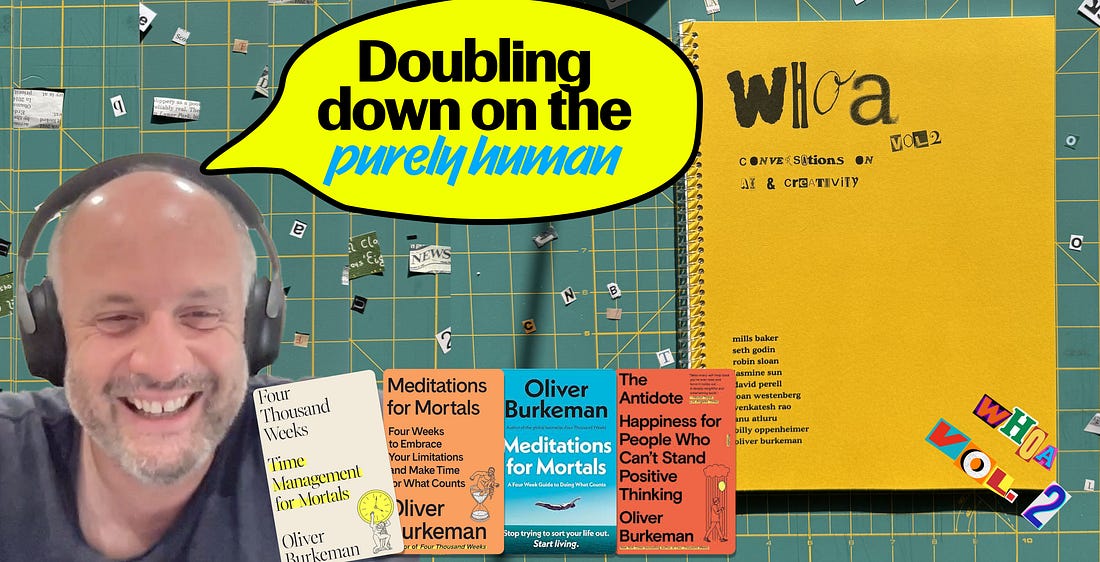

This is the final interview of Whoa, Vol II: Conversations on AI x Creativity. This project has been a labor of love (emphasis on labor!). If you’ve enjoyed these conversations, send us a signal so we know you want us to keep making them. Before we wrap the series, there’s a bonus 11th guest coming next week: Kevin Kelly (!!!) The conversation with Kevin Kelly will be exclusively for Sublime Premium subs (and paying subs of this newsletter). If you want access to the interview, consider upgrading? This series is made possible by Mercury: business banking that more than 200k entrepreneurs use and hands down my favorite tool for running Sublime.Running a company is hard. Mercury is one of the rare tools that makes it feel just a little bit easier.A conversation with Oliver BurkemanOliver is the author of Four Thousand Weeks. He formerly wrote the weekly column This Column Will Change Your Life for The Guardian. His farewell piece is a must read. It took many many emails to schedule this conversation, which I interpret as a mark of integrity. Oliver has spent years saying that the pursuit of “getting on top of everything” is a doomed project. The man lives by his philosophy. His vibe reminded me of a quote I love: “You are not paid to be on top of things. You are paid to be in the bottom of them.” In this conversation, he talks about why he believes creative work gets its meaning from the time and attention a human puts into it, what it means to make things that feel alive, and how he is planning to stay human in a world tilting toward soulless automation.  Or listen on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. (Best if you want to highlight your fave moments with Podcast Magic). The edited transcriptAlex Dobrenko: What I understand your vibe on AI to be, and you can tell me if I’m right or wrong, is you seem to have a “this isn’t great, it’s not for me” stance and you’re a little annoyed that other people are talking about it all the time. Is that how you would characterize it? Oliver Burkeman: You’re tapping into an accurate, all-purpose curmudgeon aspect of my personality that I don’t disavow. I’ve been through various phases of viewpoints. There was a brief time when I felt convinced by the science fiction doomer arguments about AI and the instantaneous eradication of humanity, but that was a little earlier, prior to the recent ChatGPT releases. Now, I find myself thinking... at the most extreme end, I feel like I’m sometimes going crazy because it seems so clear to me that certain ways people are thinking about LLMs and integrating them into their lives are not honest or authentic. The thing that specifically bothers me is people’s readiness to believe or proceed as if there’s a consciousness there. And when it comes to the creator economy, I have a growing sense that there could be an important reason not to use these tools too much. The goal is to retain a kind of raison d’être in an economic sense, to have a competitive edge. There could be a real benefit to doubling down on the purely human instead of allowing oneself to be shaped by these tools. I have a growing sense that there could be an important reason not to use these tools too much. The goal is to retain a kind of raison d’être in an economic sense, to have a competitive edge. There could be a real benefit to doubling down on the purely human instead of allowing oneself to be shaped by these tools. I’m not a total Luddite. I should say that at the same time, I’m not coming from the perspective that this has no merit, or that there won’t be great innovations in certain corners of scientific research that are really transformed by it. AD: One thing I clocked early on about all this AI stuff is the language around it. When we talk about Google, we say, “I Googled something.” I’m the one doing the Googling. But with ChatGPT, we say, “ChatGPT did it.” We gave it agency pretty quickly. I think that’s really hard to claw back. Most people don’t even realize they’re giving it soul. Why do you think that bothers you specifically? OB: What I’m about to say may cause people to completely dismiss me, but I have been uneasy about something similar all the way back to the advent of Alexa and smart speakers. I’m the kind of person who always claims I’m not going to adopt a new technology, and then I do, like everybody else. But the voice-activated stuff is an exception to that rule. We don’t have it in our house, and I’ve always felt there’s something creepy about a technology that invites me to treat it as if there’s a person there, while at the same time existing to obey my every command. Years ago, people were noticing that Alexa turned their kids into jerks because it trained them to bark commands. They had to be reminded they were allowed to bark commands at that lady in the box, but they weren’t allowed to bark commands at their mom or dad. I don’t think anything good comes from convincing oneself that there’s a person where there isn’t. It probably damages one’s relationships with real people. AD: Do you use it at all? OB: I suspect all of us are using it in ways we can’t control, with it being behind other services and platforms we’re using. Other than that, I saw somebody classify how the different generations interact with AI, and it said that for Gen X, it’s a slightly glorified search engine. I’m pure Gen X in that regard. I use Perplexity because it’s way better than Google for finding links to existing sources. It seems kind of dumb on some level to refuse to do that. One of the things that raises my hackles is the claim that the only reason not to be in awe of these technologies is that you haven’t used them enough. It’s certainly true that people who use ChatGPT a lot come to think it’s great, but I’m not sure whether that’s because they’re discovering its extraordinary depths or because they’re sort of mesmerizing themselves into the understanding that that is the way to work.

I’m open to the possibility that I’m just an out-of-touch old man, but the conscious engagement with those processes is the point. Every way in which one could skip those steps would seem to me to reduce the meaning and value of the process. AD: Do you care if other people do it? OB: When I read a piece of writing, I think it’s critical to the value of that experience that I’m reading words that emerge from a person’s own conscious, emoting, and thinking sensibility. It’s not just that the points made are good ones or that the writing is stylish. It’s the fact that it came from another consciousness a bit like mine. It’s an instance of a relationship. There was this back and forth between AI skeptics and promoters, which hung on whether AI could ever write a novel to the same standard as a human novelist. Some people said it could never happen. My argument was always not that an LLM couldn’t create something of equal merit, but that the fact that a novel was written by Jane Austen is a big part of what gives it its value. It’s not just about the end result; it’s about where the end result comes from. I think I do care that the people I’m reading aren’t heavily relying on LLMs. Someone will say, “You can’t tell, and I’m sure you’ve already been tricked many times.” Absolutely, don’t deny that at all. The point I’m making is that when I do find out, something shifts in my experience of the product completely. If we had an interesting conversation, and you felt it was a useful use of your time, but then you discovered you’d been interacting with a simulation, something really important would be sapped from that experience because it turned out there wasn’t a person there. AD: You would have felt lied to. I think people don’t like that feeling of being tricked. OB: Exactly. And I think it’s a deep point because it exists on that very obvious level of lying, but there’s also a subtler level. Almost any kind of writing that comes from a perspective that implies that the author has thoughts, feelings, and opinions is already implying that it’s human-created, even if you were technically honest about it being an AI. What are we doing here if the very act of telling me what you think is an assertion that you are a conscious sensibility, but you’re not? AD: In an earlier interview, the writer David Perell brought up that there are two types of writing: informational, where the reader is in the driver’s seat, and the ride-along style, like Joan Didion, where you get to come on the author’s journey. What do you think about that? OB: I think he’s right about the distinction, but I don’t know how big the set of things where there being no human involved isn’t a problem really is. The technical writing for how to use an appliance feels like one extreme just because we’re probably already so accustomed to poor quality in that regard. Though now I’m starting to think it would be fantastic to have beautifully authored dishwasher instructions. AD: I was just gonna say that Joan Didion writing how to use your dishwasher would be incredible. OB: Exactly. Even if that’s silly and not going to happen, that incredibleness tells you something. I wrote two books on the finitude of human life and how the fact that we have the sort of finite time is a terrifying thing, but also gives value to what we do. There is something important there too, right? If you’re going to pay for a copy of a book, there’s something important about the fact that I used up a bunch of my time to create that. And I gave that time to that when I could have given it to something else. And I thereby created some kind of value that I’ve got the temerity to ask you to pay for. And this all takes place within the world of human limitation where scarcity generates value. Something’s gone wrong with that if it actually took me none of my valuable time at all. Because then what’s going on in that transaction and why should you pay? OB: People can just tell. But even if we get to a point where people can’t just tell, it’s like... if I’m right that it matters that something is created by a human emoting consciousness, then why would that be changed by the fact that the simulation is so good that I can’t tell the difference? AD: One of the writers I interviewed, Venkatesh Rao, is very pro-AI. He uses it in his writing and said that soon he’ll just combine his AI-generated content with his other writing. He had this take that the idea of an individual being responsible for a piece of work is fairly recent—a blip in history. Before that, artists didn’t feel they were the ones who produced something; they were the vessel for God or a linguistic commons. He suggests AI is a return to that. What do you make of that? OB: I would sort of turn the tables and say it’s exactly that kind of idiosyncratic thought that has made me value the writing that I’ve come across from him. So it’s like, put that in your pipe and smoke it. I’d need some time to think about this, and I’m sure that’s an accurate account of history, but I would suggest that there’s the modern idea of the individual writer as a genius, and then there’s the idea that this person is channeling something from beyond their simple egoic consciousness, like the collective unconscious. These two things seem to be different ways of talking about the same thing. However, the kind of role of aggregate and generic writing that seems to be at the core of how LLMs work seems to be a separate thing. It’s one thing for a writer to express tales that have been in the culture forever that have moved through them, and something else entirely to take a whole collection of individuals’ work and train large language models on it to produce outputs. As I understand it, there’s something tending toward the generic, the most averaging-out of perspectives. Generic is not the same as collective necessarily. AD: I think I get what you’re saying. I also got what he was saying. I find that whoever I’m talking to, I’m kind of convinced they’re right. But I find myself asking: Do I actually feel good when I’m using AI for creative work? For me, the answer is not really. I don’t feel very creative. OB: That feeling in and of itself is why we do these things, right? On some level, we spend large parts of our lives doing this stuff in order to feel good about it. Not that you’re going to be cheery and happy at every single stage of the creative process, no one I know anyway, but that, if you don’t feel good about it persistently, then that’s its own message. AD: I don’t expect to feel cheery and happy. I actually expect the opposite. And then I expect to get to the other side of that for a little bit. But with LLMs, it kind of just cuts out that part where it’s a mess and I hate myself but that’s half the thing for me is to get to the other side, right? OB: That’s a really good way of putting it. When you say it doesn’t feel good to use AI, you’re not saying that when you’re not using AI the process is always pleasant. What you’re feeling is something like an authentic engagement with reality. You’re in life. That can absolutely be a very unpleasant experience, but it’s an alive experience. Maybe what we’re coming to here is some sort of consensus conclusion that the important thing is to have a clear-eyed sense of what you find meaningful and not outsource precisely the bit that gave it the meaning, which is something we’re prone to do in lots of areas of life. Maybe there are people for whom the meaning isn’t the process of consciously bringing ideas into connection with each other. I struggle to see what the meaning is if it isn’t that, but maybe there are other parts of the overall process that are fulfilling. AD: For the reasons you write about: “I have to save time, and I have to make money.” OB: Clearly, that’s what’s driving a lot of it. The sense that you have to do this or you’ll get left behind. I have a hunch that it might be the other way around: that my best chance of continuing to make a living doing this thing that I find meaningful is to not join the race to do what everyone else is doing, thereby making myself the same as everyone else and not worth buying the books from because what’s the difference? I have a hunch that it might be the other way around: that my best chance of continuing to make a living doing this thing that I find meaningful is to not join the race to do what everyone else is doing, thereby making myself the same as everyone else and not worth buying the books from because what’s the difference? AD: What’s your advice for writers and creatives who are worried about not fully using AI? OB: If you have a clear perspective you want to communicate, give yourself a chance to see if it resonates with people before you give up. I would definitely encourage anyone who feels a sense of dissonance between what they’re being asked to do and what they think they truly bring to the world, to focus on what they really bring to the world. I think that people are going to continue and ever more vigorously respond positively to the sort of marks of the signs of the human. The very best way to do that is just to be a human doing it rather than try desperately to create prompts for LLMs. I think that people are going to continue and ever more vigorously respond positively to the sort of marks of the signs of the human. The very best way to do that is just to be a human doing it rather than try desperately to create prompts for LLMs. AD: Yeah, I think a lot of great art that’s going to come out is going to be about that dissonance between what you feel like the economy wants you to do and what you want to do. OB: Absolutely. And I’ve always felt on this issue of, “how much do you compromise what you want to be doing in order to make it financially viable?”, there will always be people who suggest that the answer is, you compromise everything, right? You just jump on the bandwagon and go with the herd. But there’s a certain point in that process where you might as well retrain as a plumber. Why insist on continuing to travel under the banner of “I’m a writer” if you’re not doing any of the things involved in it? If you’re going to go that far, then maybe that’s just not the thing for you to be doing that would bring you alive in life. AD: I’m curious how you are actually using AI in your creative process, if at all? OB: Basically the only thing I use is Perplexity to generate lists of other sources, pretty much all of which are written by individual human beings. I am drawn to the way that Perplexity footnotes and links the sources in its output. Honestly, it feels like I’m just using it because of the famous decline in the quality of Google’s search in the last few years. Honestly speaking, that’s where I’m at with it. Maybe this will just seem completely absurd in a few years time to everybody, even to me. I still think that’s probably a price worth paying for continuing to find the experience of writing as meaningful, albeit infuriating and maddening, as I currently do. AD: How would you describe your relationship with AI? OB: I don’t think in relationship terms. When it comes to AI, I don’t think you only have to have relationships with living beings, right? I feel like you can have a relationship with a landscape or a place. So it’s not like the word is completely inapplicable, but no, I try quite hard to keep it the kind of relationship that I have with my MacBook or the pens I use. It’s a tool and I don’t want to forget that. AD: What do you wish AI could do, but fear that it never will? OB: Again, I’m not sure that I want it to do anything that it doesn’t yet do. Obviously, if there are specialist domains where it can cure cancer, I’m not going to be sitting here saying, don’t do that, because I’m not completely insane. But I start from a place that makes me not want to answer that question, I guess. AD: Everyone is making predictions about AI. Let’s make a prediction about humans. Where do you think humans will be in 10 years? OB: The best gamble you can make about how we’ll be in 10 years is how we are now. I think we will be messy, at each other’s throats, boundlessly creative, and constantly on the verge of destroying ourselves—but not actually doing so. AD: What question about AI and creativity isn’t being asked enough? OB: I don’t know how to phrase this, but it is that question of how much of the value of creativity is connected to the sentient, emoting, thinking awareness of the creator. We talk about whether AI is or could be conscious and what that would mean, but I think we could do with talking a bit more about how human creators are conscious and why that matters so much to what they produce. AD: Cool. And last question, what do you wish people talked about more instead of AI? OB: Almost anything. OB: I am working on a new book. It’s very hard to exactly say what it’s about at this point. I’m not being coy. I’m just struggling for the language. But it is something closely connected to this idea of aliveness or what it is that gives human life that feeling of being worth living. AI is definitely implicated in this discussion, although I’m not going to write a book on AI because there are enough of those. AD: I can’t wait to read it. This was awesome. Thank you. OB: It’s a pleasure. Thanks for your enormous patience in setting this up. I’ve appreciated that. |