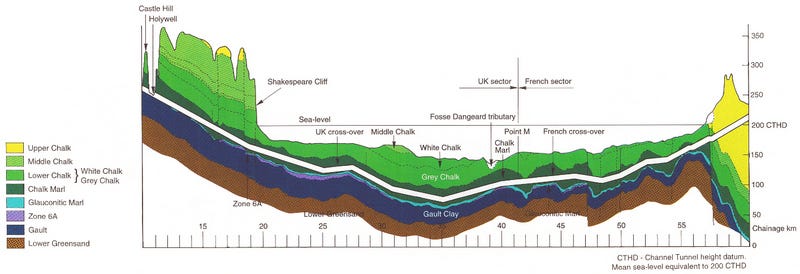

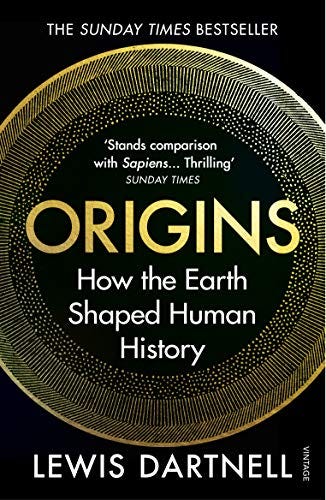

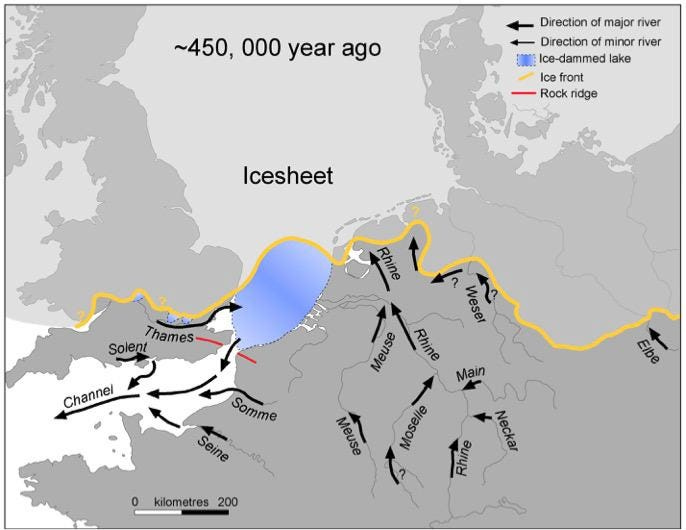

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a science-obsessed newsletter about curiosity and awe, weirdness and wonder. This edition is a previously published story (I’m only writing brand new pieces for paid supporters until season 8 kicks off in a few weeks) and it’s from 2022, and a follow-up this season’s fascination with massive geological spasms of chthonic fury. Let’s head over to…well, what I previously thought was the unlikeliest place in the world for Big Geological Drama. These are the White Cliffs of Dover, on England’s extreme southeast coast. They’re just over a hundred metres tall and stretch for about 12 kilometres, they’re made of chalk streaked with black flint, and they’re all that’s left of a strip of land that once stretched 30-ish kilometres to modern-day France. I already knew two of these things - and I thought I knew about the third. I knew that the recent history of our planet (that’s the geological version of “recent” that’s measured in hundreds of thousands of years) is one of waxing and waning ice ages, and when the water of the oceans was mostly locked up in great glaciers hugging the polar regions, you could have walked across the bed of what’s now the English Channel. Have you ever sat at a cliff’s edge and tried to imagine away the sea? It’s fun! Have a go. Great workout for the imagination. What would be left, with all that water gone? I do this a lot, and it usually makes me feel dizzy and nauseous and deeply appreciative of the ground I’m standing on. (Once I even threw up! Imaginations are hilarious.) In most cases, with the ocean removed, you’re suddenly thrust high into the air. Before you were at “sea-level” (aka. as low as you can go), and now you’re in the highlands. You’re looking out over a valley, or a canyon, or peering over a precipice. Much more of everything is now down. Just as our inability to see far underwater turns the sanity-bending scale of our ocean floors into something we hardly think about, the presence of sea and its light-reflecting qualities focuses our gaze and our thoughts on the shoreline, not on what it’s interrupting. But if we could truly see what’s down there? Perhaps we’d experience a version of The Overview Effect (the humbling perspective shift that left William Shatner so flummoxed during his recent trip into space), but going the other way, downwards, towards the vastly greater volume of space on the surface of our planet that most of us barely think about? What you’d probably see from atop the White Cliffs of Dover is a vast, muddy marine valley, 26 miles wide at its narrowest point, and mostly lined with chalk, through which the Channel Tunnel cuts: As I’d been taught at school, millions of years of flowing seawater had gently nibbled down this landscape from whatever it was to start with. Probably a river? A river that gradually widened over inhuman amounts of time, tearing away more and more of the relatively soft chalk until Great Britain (apart from times when the sea level was unusually low) was an island. This is the gradualistic, deep-time model of geology that ties in with the fashionable uniformitarian ideas of pioneers like Lyell and Hutton. This slow-but-sustained thinking was partly a reaction to catastrophism, the belief in sudden great dramatic upheavals that always seemed to turn back to stories of Noah’s Ark and the great flood that served as its backdrop. Well, pshaw and poppycock and flapdoodle to all that guff: couldn’t Science do better than merely acting as a prop for the Bible? And wasn’t there in fact a wealth of empirical evidence for incredibly-long-term processes making such changes on their own? Sure! But hey, why can’t both be correct? This is what geologists believe today (and to be fair to Lyell and Hutton, they both accepted the power of sudden great changes, although as rare exceptions to the rule). It’s now understood that the world changes gradually, and the world changes suddenly, and both can apply at any time. But in particular, it’s now understood just how amazingly quickly - and how enormously - the surface of a planet can be altered by staggeringly violent events that we’d have labelled “natural disasters” if we were unlucky enough to be around to see them. Here’s one speculative example: Ye gawds. And that asteroid that famously wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago? From a study published on October 4th, it seems to have generated tsunamis on a scale I doubt many of us considered possible until now:  66 million years ago, a huge asteroid collided with the Earth, wiping out most dinosaurs (& 3/4 of plant & animal species) on the planet. It turns out, it also sparked a "megatsunami" — one with 30,000 times more energy than the 2004 Sumatra tsunami. Wow. The tallest of these megatsunamis are projected to have been the same height (around 4,000 ft) of the wave from that bloodcurdling scene in Interstellar: So, yes. BIG THINGS CAN HAPPEN SUDDENLY. Regarding the shores of my own country, I really should have kept this in mind. I’ve been writing about such things since February ‘22, starting with the Zanclean Megaflood (the reason many of you started reading this newsletter, thanks to a viral Twitter thread), and the Storegga tsunami that engulfed what remained of Mesolithic Doggerland around 8,000 years ago. But the English Channel? Oh come on. This is the UK. Things have a habit of not happening here (earthquakes, volcanoes, revolutions, tolerable weather, displays of genuine emotion). That’s what it’s famous for! What could possibly happen here that could be labelled High Drama? Well, one answer to that question could be “everything in our politics since 2016” - but the more considered and relevant scientific response is “everything happens everywhere, if you give it enough time.” And this is how I learned that around 425,000 years ago, the island of Great Britain was wrenched away from Europe in a fashion more dramatic than the fevered dreams of any hard-line Brexiteer, by a single flood so violent that it could part continents. Here I’m indebted to Professor Lewis Dartnell, whose superb book Origins tipped me off about the Dover megaflood for the first time:

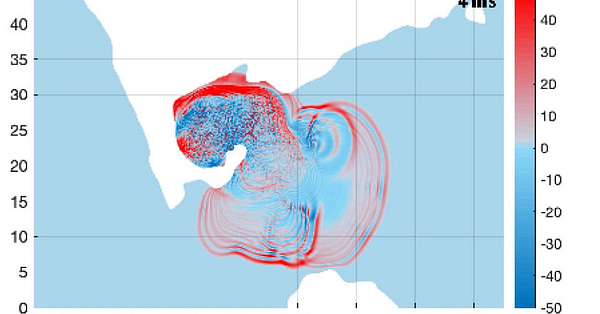

The bathymetric data collected and studied by marine geophysicist Jenny Collier of Imperial College and colleagues was published here in 2015, and showed 36 underwater “islands” formed of bedrock - the harder stuff left exposed once the softer surrounding material had been scoured away. This supported an earlier study by Sanjeev Gupta of Imperial College London showing the marks lefts on the sea floor by a sustained torrent of water, in much the same fashion as those left on the floor of the Gibraltar Strait by the proposed Zanclean flood. Dartnell continues:

Gupta’s team estimated the flood was pumping 1 million cubic metres of water per second - for months. That’s roughly a hundred times the Mississippi river today, and a thousand times the normal flow of the Rhine. I’d consider that completely insane, if I didn’t remember than the Zanclean megaflood was a hundred times more powerful still. Nevertheless: whew. Was anyone around to see this monster of an event? Possibly! There are footprints of early hominids in modern-day Norfolk dating back 900,000 years (Homo sapiens would take another 600,000 years to arrive, as far as we know). But they, like every other living creature, must have retreated from the advancing glaciers of each ice age to seek out more habitable lands further south, only to return (as a species, I mean) when the world’s climate warmed again. (I’d prefer to think there was nobody around to see the English Channel megaflood. There’s only so much the human mind can take.) So that’s what you’d see from the cliffs of Dover, if the seas boiled away before your eyes. You’d see the remnants of an ancient chain of waterfalls on a scale dwarfing anything visible today. That’s what our Chunnel trains whisk us under when we go to France, and that’s what our aged but stalwart ferries sail over. Then you’d have to imagine the chalk under your feet stretching forward into thin air, 110 metres above the now-placid sea, and forming a ridge of land that runs almost to the horizon, to the distant smudge of shadow that marks the French coast - and then imagine it all being torn away in front of your eyes, until you were suddenly standing on an island. As we say round these parts: blimey. - Mike If that gets you wondering what else you’re regrettably unaware of, I have a paywalled piece about some everyday marvels we take for granted that might make you feel grateful (rather than horrified!) about the time we live in. If you’re interested in reading it, and everything else in my archives, it’s a good time to upgrade - because right now, all paid subscriptions to Everything Is Amazing are 10% off. In doing so, you’re also helping me keep this project running. This is a one-man operation without ads or sponsors or any of that cluttery nonsense - nothing but the kind support of EiA’s 820+ paid supporters, which keeps me accountable to them (and you) alone. If you’ve enjoyed any part of Everything Is Amazing so far, and want to see it grow and get more ambitious/reckless/weird, an upgrade at any level is the very best way to help me keep this thing alive. Click below to sign up with a 10% discount: Thank you so much! Images: Peter Mason; The Geological Society; Science.org; Jenny Collier. |