Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity, attention, wonder and great-smelling air. This edition is taken from behind the EiA paywall, and is part of a series I ran last year about the surprisingly weird science of human memory. (On that note, if you want to read everything this newsletter has to offer & help me shovel more coal into its boilers - DISCLAIMER: just a metaphor, because this newsletter is sustainably powered by sunlight, coffee and semi-clueless enthusiasm - then you now only have 5 more days to take advantage of the between-season discount on all subscriptions! Click here for the details.) In this edition, we’re looking at the alarming havoc our minds can wreak upon our mental biographies and sense of identity - and it starts with the stupidest thing I’ve ever done on a bicycle. “Right, lad. LET’S DO THIS.” I line up on the homemade bike ramp halfway down the street, cycle madly towards it in a blur of pedals and knees - and it’s only when I launch myself into thin air that I realise what an endlessly awful idea this is. This isn’t the usual way I do things as a teenager. I’ve always had a highly active imagination and I’m a shameless coward, so I’m normally quick to catastrophize my way out of attempting the kind of activities teenagers from British rural towns might do to numb their existential horror: yes that might pass the time, John, but I can imagine laughing if I read it on someone’s gravestone, so no, I will not be joining you this time. Best of luck! I hadn’t successfully avoided every stupid idea, though. In the frozen dead of a Yorkshire winter, a gang of us discovered a burnt-out car at the back of our local park late one night, and had the brilliant notion of inexpertly sawing the roof off it, flipping it over and turn it into the Death Sled™. With four of us clinging to the jagged razor-sharp struts at each corner and the rest giving us a shove, we started down the slope of a hill. Success! It worked! Um - far too well, actually! Had we discussed the concept of braking? We had not. Traversing the 300 metres to the park entrance in about ten seconds, we saw far too late that nothing prevented us from skimming up the sloping tarmac path and flying out into the main road to pancake ourselves into a row of shops on the far side. It’d be the stupidest of ends. Nothing could save us now. But then, a winter miracle! With a clang, a hidden boulder knocks us sideways, away from the path and into the side of its grassy embankment. With a deafening, metallic PWONK! the Death Sled™ springs into the air, scattering us in all directions - at which point we scramble to our feet and leg it before someone calls the police about all the screaming. This lucky escape has left me cautious about life and quick to say no. But now, with my bicycle under me and the ramp ahead of me, for some reason, this natural line of defence fails me when I need it the most. Here’s the scene in detail. After watching an episode of The Dukes Of Hazzard, I decide that what my credibility needs is to be seen to be flying through the air like a bird - so I’ve stacked a pile of bricks in the road and laid a plank up one side of them, in an attempt to coax out the cooler kids and their bikes at the bottom of my street. What I lack in experience, foresight and almost every other survival trait evolution has attempted to bestow upon me, I’ve made up for with wild enthusiasm (an early sign of how I’ll approach the rest of my life) - so I make the ramp ten bricks high. Now I see my error. Nearly knocked senseless by the impact of hitting the bottom of the ramp, I proceed up it at great speed. I know it’s probably too late to chicken out - but I try it anyway, squeezing the brakes so hard they’re in danger of snapping. The next memory I have - and it’s a vivid one - is running laps around my Mum’s green Vauxhall Nova. Round and round and round I go, bawling my eyes out and unable to stop running or crying, because the pain from my broken arm, which I’m cradling with my other arm, is so utterly unbearable. I continue to do laps until the ambulance arrives. Even now, over thirty years later, when the weather is changing and the air-pressure is rising or falling, I feel it in my then-smashed arm as a throbbing ache (yes, medical science is at last concluding that this is a real thing). So, that’s my bike ramp tale. It’s not a fun story, but it’s a good one to scandalize anyone who hasn’t heard it. And I really, really wish it was true. Let me be clear: the above account is exactly and precisely what I remember. I’m not consciously embellishing anything, I’m not pulling the wool over your eyes for entertainment purposes, or knowingly telling you porkies here. According to the inside of my head, this is a true and accurate story of what happened. Unfortunately, my version wasn’t corroborated by a key witness to that absurd disaster. A decade later, I got talking to my late Ma about it (she wasn’t late at that point, I should add, it wasn’t one of those kinds of conversations) - and she didn’t remember me running around her car. When she found me, I was sat on the grass verge on the outside of our garden hedge, rocking back and forth & howling with pain. She swore blind to this - and yet I remember none of that myself. In my memory, I was running, running, running until the ambulance arrived - except, come to think of it, she couldn’t remember if it was an ambulance or if she drove me to the hospital herself…? When my Ma told me all this, I was indignant. OH COME ON. Was I not the one to whom all this happened, feeling all the feelings, dealing with the agony? She was just an onlooker and so must have muddled things up. Surely *I* was the most reliable source of information here? I didn’t think about all this until I recently started looking into the mind-bending study of false memory - because it seems, entirely contrary to basic common sense, that your presence on the scene of an event may actually make your memory less reliable than a remote observer. Since we construct so much of our personal identities on our memories, the implications here are extremely unsettling, and have the potential to call into question…well, everything about us, really, as we dip a toe into the science here. What’s left of you if you can’t even trust your own memories? Let’s take a look. In 2012, science writer Annie Murphy Paul published a summary of recent research into brain activity while test subjects were reading novels, in a much-quoted piece called “This Is Your Brain On Fiction” (here’s an archive link):

I’ve referenced this article quite a few times when teaching storytelling as a travel writer - the richer the sensory detail you include in your story, the more your reader will feel like they’re having a “real” experience as they vicariously follow your adventures on the page or screen. More recently, I started learning how how unreliable our brain’s perceptive systems can be, tuning out great patches of our vision and hallucinating fabrications into the gaps. I learned about impossible colours - and how virtual illusions can leave us utterly convinced of seeing things that never existed. In short, our grasp on external reality seems a lot more tenuous than many of us are comfortable believing. (And this is from a modern scientific perspective, mind.) But what about our inner worlds - the places we spend so much time trying to understand ourselves, where we try to better anchor our sense of self to give us the strength and stamina to wrestle with the baffling mysteries of Other People in all their alien and unpredictable ways. What do we actually anchor that Self in? It’s…a story, isn’t it? A story about the kind of person we are, the ideas and principles we stand for and against, the ways we want to treat others, and how those ideas measure up - or, to our shame and regret, fail to measure up - with our actual behaviour. And, above all, it’s a story built from a framework of memories: I Am Because I Did (And/Or Was Done To). Without the reassuringly sturdy edifice of our personal history to place ourselves within, how could we ever know who we are and where we belong? If those walls were called into question, if even our most fundamental memories couldn’t be trusted, where would that leave us? We’ll get to that. But first, let’s look at the curious case of the man who imagined himself into the wrong helicopter. In 2015, journalist and television anchor Brian Williams stepped down from his position as host of NBC Nightly News and took a 6-month suspension without pay. The reason was a story he’d told about his time reporting on the Iraq War in 2003. In it, he claimed he was being flown in a military helicopter that had been forced to land after being hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. Once army personnel came forward to confirm he hadn’t been in the helicopter that came under fire, other journalists did some digging:

Being caught out telling a falsehood like this is embarrassing enough when you’re amongst friends - but having it happen to you on national TV in front on millions, on a news channel with a reputation built on delivering the facts, is a career-ruining blunder. Despite an apology in which Williams admitted he seemed to have inadvertently conflated what really happened - well, you can imagine the reaction, especially from Iraq War veterans. Since Twitter was a thing by then, the hashtag #BrianWilliamsMisremembers did brisk business on there for a few months. What happened here? Why would a highly experienced journalist allow himself to make such an easily falsifiable gaffe on air - the kind he must have known would get him fired when the truth came out, as surely it must at some point with the amount of witnesses available? (As a lie, it’d be breathtakingly inept - which lent weight to the idea that it’s not a lie at all. It may be factually untrue, yes, but if the intention isn’t to deceive, maybe it’s something other than a “lie”?) To the end of his TV anchoring career in 2021 (now on MSNBC), Williams claimed he never had a clue his memory had failed him so profoundly and so damagingly. But, hold on. He was there. This wasn’t him mangling the details of a third-hand account. This was an event that happened - or rather didn’t happen - directly to him. How could be possibly have got this wrong as the man on the spot at the time? (As his critics yelled: hey, you’d think you would remember being hit with a rocket-propelled grenade?) In a study published in the journal Memory in 2003, two groups of test subjects were presented with what turned out to be a staged robbery. Half of them (62 of 122 participants) experienced the fake robbery in person at the scene - while the other half watched a video recording of it. After the dust had settled, they were tested on what they could recall - and something surprising and counter-intuitive became clear. Those who watched the video of the robbery recalled more of the event, more accurately, than those who were present at the time. Both groups still disagreed on some of the details, exhibiting false memories of things they’d expect to see at a crime scene but weren’t actually present - but taken as a whole, the second-hand observers had a better recollection of what actually went down. This is a small study in a rapidly expanding field, so I’ll try to not put too much weight on it (especially as I’m a professional science enthusiast rather than a researcher), but as a sign that first-hand experience maybe isn’t everything, it’s unsettling to say the least? The person with the highest public profile in this field of study is probably psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, who has tested the many ways that language could actively shape someone’s memories. In showing the ways fictitious traumatic memories can be implanted in people, and in her willingness to offer herself as a consultant for over 300 court cases to date (including, most notoriously, Harvey Weinstein’s), she’s become an enormously controversial figure - as is explained in this fascinating profile of her in the New Yorker. If there’s one thing she’s keen to emphasize, it’s the fickle role of emotion in memory formation. Yes, we seem to remember best the events in our lives with the biggest emotional highs and lows - but that emotional intensity also makes them susceptible to self-editing after the event, like the kind of muddled conflation that got Brian Williams into trouble with NBC. In Loftus’ words:

Pondering all of this may feel like falling down an imaginary well (or riding a Death Sled™ to certain doom). It’s not for nothing that uncontrollably dwelling on false memories has been diagnosed as a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. It’s a pretty pickle. Even if the ultimate dream of memory retrieval is realised and we find a way to strengthen our memories to the level of ‘total recall’, as I wrote about in the last edition of this series, what we’re recalling could still be riddled with false memories and therefore utterly unreliable! (As suggested by this research.) Worse still, if we can both be remembering the facts of something with total and utter diamond-hard certainty, and one or even both of us is factually incorrect, especially the one with more personal experience, what happens to that discussion we’re trying to have? I guess one answer is “look at social media in 2024.” But it does prove an additional challenge when dealing with conspiracy theorists who are absolutely convinced of their version of reality and have “proof” (including their own self-falsified memories) to back it up. That said, an interesting piece recently in New Scientist featured a study that suggests they often aren’t as convinced as they claim to be, and I’m taking this opportunity to quote the full sub-heading because it’s glorious:

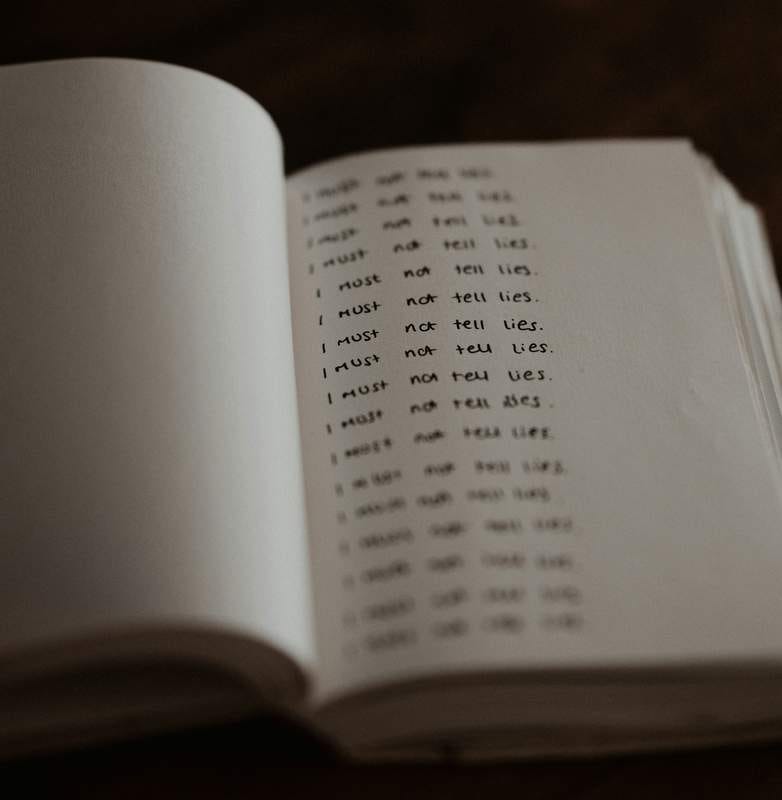

But perhaps all this is a timely reminder of two things. Firstly, when we rely on our own utter certainty, especially of things we’ve experienced in person, we could actually be opening ourselves up to a greater chance of error than someone who isn’t as emotionally invested - so perhaps we should apply our curiosity extra-rigorously to the things we’re most likely to defend the hardest. (I know that sounds….really exhausting, but I’m also not suggesting you should spend all your time grappling with bad-faith arguments. Just, you know, treat your memories as a set of best-fit theories, if you don’t do that already. And don’t argue with idiots. Ta.) And secondly: to avoid your personality flying to pieces, how about leaning into the findings of Annie Murphy Paul, and start regarding yourself not just as an amalgam and summation of your memories of everyone you’ve been and everything you’ve done (both of which may now be far less accessible to you than you think) - but as an ongoing story of your own continuous re-imagining? No, really. Isn’t that one of the great human inventions, from which all world cultures sprang? Aren’t we all the products of stories that we’ve acceptingly or unwillingly taken on board to rewrite the cognitive software governing our lives? The trick here (apart from maintaining some kind of grip on reality, of course) is not to fall into the trap of regarding stories of identity as unassailably objective scientific fact - for example, with the definition of a “nation”. Identity is stories all the way down, and instead of feeling hemmed in and victimised by yours, how about acting like the author you actually seem to unconsciously be at the neuron-by-neuron level, with all your self-rewritten components in the form of memories? How similar to who-you’ve ended-up-as is the person you want to be? What would that person be doing, and how would they be acting? How about trying to do a few of those things too, until your fickle memory does its thing and you completely forget you haven’t been like that until now? Yes yes, all very Instagram-inspirational, Mike. Returning to ground level, here’s a more concrete tip. If you want to keep your memories as error-free as possible, work on your sleep routine. Not only is sleep deprivation a living nightmare for your mind and body, as I previously explained here, it’s also an accelerant for false memories. The results of this study showed that “multiple nights of restricted sleep result in an increase in false memory formation in adolescents, a group previously thought of as being resistant to cognitive impairment arising from sleep loss” - so goodness knows what it can do to us adults. In short: our memories may play tricks on us - but that doesn’t mean we have to help them do it. Thanks for reading, M If you’re interested, I am in fact currently working on my own sleep routine - and writing about it for EiA’s 820+ paying subscribers, for at least the next month. If you want to read it, and the rest of this series on human memory (which includes the unnerving implications of being able to remember every day of your life, and the role of handwriting in making things stick inside your head), I’d be thrilled if you were kind enough to upgrade to a paid subscription at a monthly or yearly level. (Also, if you’ve enjoyed any part of Everything Is Amazing and want to see it grow and get more ambitious/reckless/weird, an upgrade at any level is the best way to help me keep this thing alive.) Click below to sign up with a 10% discount: Thank you! Images: Neurolink; Mr Xerty; Jean van der Meulen; Annie Spratt; NEOM. |