Before I launch into a shortish rant, I ought to mention that my novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster makes a wonderful holiday gift for your loved ones. Especially your parents or your adult children — it’s a book about learning to understand your mother as a human being, rather than a mythic figure from your childhood. Lately, I’ve heard from a lot of folks who shared it with their moms and had some good conversations as a result. As always, get it from Green Apple and I’ll sign, personalize and doodle in it.

Also, this Tuesday I’ll be at Booksmith for the launch of We Will Rise Again, an anthology of stories about resistance and progressive movements. Come say hi!

One thing that strikes me is weird about classic science fiction is how soon many of its predictions came false. Star Trek chose to put the Eugenics Wars in the 1990s, a mere 30 years in the future. Doctor Who made all sorts of predictions about the 1980s, including the arrival of Earth's twin planet in 1986. Let’s not even get into Back to the Future Part 2. And then of course there's Space: 1999, which sets Moonbase Alpha only a quarter century into the future.

(And before anybody says it, yes — science fiction does not predict the future. I'm getting to that.)

Many science fiction novels also committed themselves to wildly specific claims about that would be falsified in twenty or thirty years. (Hence the popularity of all those endless articles about predictions that science fiction got wrong, back in the 2010s.) This hubris feels a bit baffling, given that people could have simply picked a longer time horizon and escaped being falsified quite so soon. Why did classic science fiction make this choice? I can think of a few reasons.

First of all, a lot of these works were being written and produced at the end of a time of tremendously rapid progress. We’d gone from an earthbound species to a space fairing species in a remarkably short time, and it might have seems plausible that after landing on the moon, accomplishments such as colonizing Mars or establishing a permanent human presence on the moon would soon follow.

On a related note, we hadn't yet learned enough about the difficulties of space travel, and the limits on certain kinds of technological progress. We didn't understand quite how impossible it would be to send humans to another star system, for example. We didn't understand fully about the toll of long-term radiation exposure on the human body, not to mention the bone density loss and other health effects from sustained microgravity. We overestimated how quickly we could make advances in spaceship design.

They're also seems to have been a reality distortion field around the year 2000. People as late as the 1970s talked about 2000 as if it was impossibly distant, merely because it was a year that started with a different digit. I don't think of the 2050s as being unimaginably far off, but this seems to have felt different. (On a related note, this is why we had the Y2K bug that nearly caused widespread chaos in 1999, because we couldn’t process that 2000 was coming so soon.)

Finally, I think people overestimated the appetite of governments to keep pouring resources into space exploration — government funding being the only way that you really see rapid progress in most areas of science and technology. The space race was an artifact of the Cold War, and we soon moved on to other forms of great-power competition. I think that part of the undue optimism about near-term advances had to do with a belief in human nature: that we were by our very nature curious innovators, who would prioritize the pursuit of knowledge over all else. (Rather than pouring our resources into building machines that would tell us what we want to hear.)

In any case, I was thinking recently that I'm grateful to so much 20th century science fiction for proving itself wrong so early. Because I believe that visions of the future should come with an expiration date. They should become obsolete at a certain point, lest we become bogged down in the detritus of ancient visions of what’s to come.

It's not enough to say that science fiction does not predict the future, because of course, nobody can predict the future. (Though in fact, some future events are easy to predict. We know climate change will continue to worsen. The A.I. bubble will burst. Everyone who is alive now will die someday, and every company now operating will eventually go out of business. There will be more wars — because there are always more wars. Capitalism as we know it will come to an end. We just don't know when most of these things will happen, or what form they will take.)

Anyway, nobody can predict the future, including science-fiction authors.

But we have to go further and say that visions of the future are passing daydreams: they pop like bubbles, leaving almost no trace. Not only do people conjure the future as a way of discussing the present — see: the original Star Trek's obsession with the Vietnam war — but they emerge from a set of assumptions rooted in a specific cultural moment. Even more than that, they are deeply idiosyncratic and quirky. This is especially true if someone tries to extrapolate based on current trends, or use known facts to make projections.

We should, in fact, treat future predictions as colorful hallucinations. As brief lapses in reason, which nevertheless can eliminate important truths in the same way that a poem or work of surrealism can. Or an abstract painting. It's not just more art than science, it's more art than most art. Above all, when an individual takes it upon themself to tell us what will happen years from now, we should treat this as telling us even more about that individual than about the time and place they live in.

This way of looking at visions of the future makes me love them more — not less — because of how deeply frivolous they feel. That’s part of why we love retro-futurism in the first place: because of how weird and silly it feels. The future can be honestly terrifying to contemplate, but dwelling on the gooftastic imaginations of various oddballs can help make it feel better. And at least we know the future will probably include cake.

Thanks to Adam Becker for the conversation that helped inspire this newsletter!

Music I Love Right Now

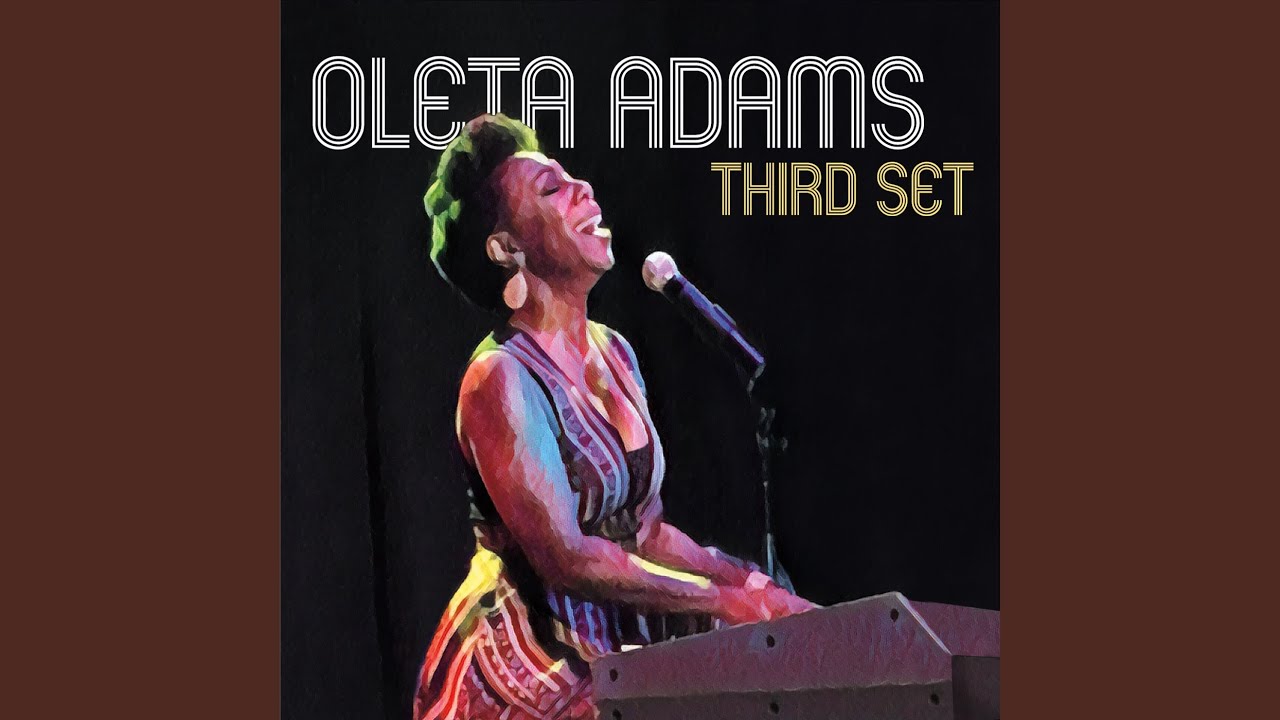

I had listened to a ton of Oleta Adams back in the day, but hadn’t learned much about her until recently. I only just learned that she was singing in an airport hotel lounge in the 1980s, after a couple of failed albums on tiny labels. And the pop group Tears for Fears were passing through Indianapolis and heard her sing, and then came back months later to track her down and ask her to join the group. She became their keyboardist and sang on some of their songs, including the single “Woman in Chains.” This gave me a whole new respect for Tears for Fears.

Anyway, lately I’ve been listening a lot to her 2017 album Third Set, which sounds like a live-in-studio recording featuring a really killer band. Adams has an incredible soaring voice, but also is a brilliant piano player, which is on full display here. It’s a sweet jazzy album that I can listen to at bedtime, but also wake up to first thing in the (mid) morning. Adams also passes the acid test many other artist fail: covering Joni Mitchell. She does two Mitchell songs here, and I strongly prefer her version of “River” to Mitchell’s own. So I recommend hunting down all of Adams’s albums, but especially Third Set.

This was issue #224 of Happy Dancing. You can subscribe, unsubscribe, or view this email online.

Powered by Buttondown, the easiest way to start and grow your newsletter.