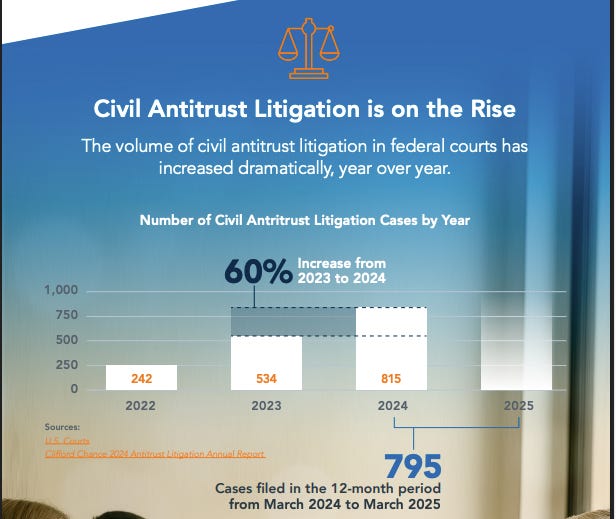

| Last week was Thanksgiving, but there was a surprising amount of monopoly-related news nonetheless. Famed Avatar director James Cameron went after Netflix for its attempt to buy Warner Bros. Discovery, pro golfers are acknowledging the LIV Golf/PGA Tour merger is unlikely to happen, and NASCAR is in a life-or-death monopolization trial starting tomorrow, brought by Michael Jordan, of all people. I want to focus a bit today on antitrust law itself. After the loss in the Meta trial, and the Trump DOJ settling the RealPage rent-fixing suit, I started to see more chatter among fancy lawyers that the populist era of antitrust is over. And that got me thinking; it’s been a little over a year since Trump’s election, so it’s a useful moment to look at what Trump has done with the Biden antitrust legacy. Has Trump reversed it all? Or built on it? What is the legacy of antitrust populism so far? It’s a debate that quietly stirs some real passion among those who control capital. Today, as Wall Street celebrates a merger boom, bankers want to believe that the good old days are back. Big tech supported think tanks are trying to argue that the populist approach to antitrust is over. But there’s another side of the debate. Oddly enough, the Wall Street Journal editorial page is stating that Trump is just as ‘bad’ as Biden on antitrust, even as the New York Times editorial board had a piece criticizing the Trump administration’s flabby antitrust approach. Why are participants all over the place on the status of antitrust law? Here’s what’s going on, as best as I can tell. From Reagan to Obama, competition policy used to be a genteel space, politely controlled by lawyers, economists and bankers in a ‘bipartisan consensus’ whereby consolidation was seen as virtuous and size was nothing to be afraid of. As one memo from Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisors put it, “Large size is not the same as monopoly power. For example, an ice cream vendor at the beach on a hot day probably has more market power than many multi-billion-dollar companies in competitive industries.” Under Obama, for instance, the Federal Trade Commission used authority to go after powerless actors, such as Uber drivers, church organists, bull semen traders, and ice skating teachers. Meanwhile, that same commission allowed Google to buy Waze and Facebook to buy Instagram and WhatsApp, creating modern big tech giants. Similar roll-ups happened in everything from pharmacy benefit managers to ticketing, with a fat and happy antitrust bar celebrating themselves. Joe Biden broke from this tradition, appointing aggressive enforcers Lina Khan at the FTC and Jonathan Kanter at the Antitrust Division. Khan and Kanter brought a series of lawsuits in an attempt to return anti-monopoly law back to its historic American roots. Biden even gave a speech in 2021 naming Robert Bork by name as the ideological cause of concentration in the economy. Biden’s enforcers were reviled, because they broke this consensus of the nice happy little antitrust world. When Trump won in 2024, things changed, but not necessarily in a useful way for the antitrust bar. Trump has overseen a very strong pro-monopoly framework, but he has not actually returned to the certainty of yore. Payoffs and political connections with Trump matters, not the more polite kind of corruption that flourished in the days of Bush and Obama. And politics is now important. For instance, four days ago, Trump’s Secretary of Agriculture, Brooke Rollins, went on a podcast of cattle ranchers, laying into big meatpackers. That would never have happened in previous administrations. That’s why the WSJ equates Biden and Trump, because antitrust lawyers have to explain to their clients why they have less control than they feel they should have. But all that said, what does the evidence show? There are two axes through which to understand competition policy. The first is the law. Law is shaped by a delicate dance among enforcers, courts and legislatures. While there’s a Schoolhouse Rock version showing that laws are passed by legislatures and then go into effect, the reality is more complex. How enforcers implement laws, how judges interpret them, and whether private lawyers take them seriously is as important as the text passed by legislatures. That’s why people see Lina Khan as a meaningful symbol. The second part of the story is policy, which is organized by the executive branch’s priorities. Most media reporting is about policy, which definitely matters. But the law needs some focus. We’ll start with that. While some of the legacy of Khan and Kanter have been rolled back or altered, there’s a good amount that hasn’t been. Here are some doctrines of law that remain useful. Revived monopolization law: From 1998 to 2020, monopolization law was a dead letter, with the DOJ not filing a single case using this body of law. The main block was something called Trinko, a 2004 Supreme Court precedent that supposedly made it difficult to bring cases. The Antitrust Division under Jonathan Kanter attacked this obstacle head-on, winning two Sherman Act cases against Google. In addition, the FTC/DOJ won motion to dismiss legal hurdles against Amazon, Apple, Ticketmaster, Visa, and private equity-owned US Anesthesia Partners, among others. With a bevy of private Section 2 cases, it’s clear the Trinko era is over. Oh, and the Antitrust Division even restored criminal monopolization law. Strengthened antitrust laws enabling right to repair: One of the last lawsuits filed by Lina Khan’s FTC was a Sherman Act and FTC Section 5 Act claim against John Deere for having “illegally restricted the ability of farmers and independent technicians to repair Deere equipment.” In June, a court upheld the FTC’s legal analysis. The DOJ filed a statement of interest in private cases, and states are passing laws. While current FTC Chair Andrew Ferguson dissented from the Deere case, his FTC has continued to intervene in private litigation on behalf of people who want to repair equipment. Increasingly, it’s illegal for monopolists to thwart the repairs of the equipment they provide. Labor and antitrust: Under Biden, the FTC and DOJ focused on labor markets, using a variety of laws, such as securing the first criminal wage fixing conviction, preventing civil information sharing and no-poach agreements, strengthening the Packers and Stockyards act, and using merger law to help workers, such by blocking the Penguin/Simon & Schuster on labor grounds. They filed statements of interest in private litigation around the NCAA, revised payment terms for chicken farmers, and fostered a settlement in esports. The Trump Antitrust Division is continuing this approach, recently convicting a nursing home executive for wage fixing. And the Trump FTC claims they have a task force on labor. Restored the Robinson-Patman Act: The FTC sued alcohol distributor Southern Glazers in late 2024 for violating the Robinson-Patman Act’s prohibition on price discrimination. It was the first RPA lawsuit in decades from the FTC, and a judge upheld the FTC’s legal claim in April of this year. The lawsuit is ongoing. The FTC also sued Pepsi under a similar claim, but the Trump’s FTC dropped the suit. Unfair Methods of Competition Law: Section 5 of the FTC Act bars ‘unfair methods of competition,’ a capacious standard narrowed radically by the Obama administration. Under Khan, the Federal Trade Commission restored Section 5, and in particular sued the big three PBMs for hiking insulin prices with illegal rebates using this particular doctrine. Exclusive Dealing Law: The FTC sued herbicide producers Syngenta/Corteva under Section 3 of the Clayton Act, which bars exclusive dealing. That suit passed the key legal hurdle, motion to dismiss, and is ongoing. This area of law was not used by the FTC for decades. Merger law: When the Fifth Circuit upheld the FTC’s lawsuit against Illumina’s purchase of Grail, it was the first win for an agenda against a ‘vertical’ merger in four decades. Khan and Kanter established a host of new tools, like labor buying power, ‘potential competition doctrine,’ ways of understanding combinations of data, a new form for reporting mergers, and new merger guidelines. Interlocking Directorates: Section 8 of the Clayton Act prohibits someone from being on the board of two rival firms. It had never really been enforced, until Kanter actually forced a host of resignations, including cable titan John Malone. Noncompetes: While the FTC rule against noncompetes lost in a court in Texas, and the Trump FTC stopped fighting for it, Khan did establish that a non-compete could be unlawful. And a host of states and cities have been passing laws restricting or eliminating noncompete agreements. Junk fee rule: Khan’s FTC passed a rule against hidden junk fees, the Trump administration has overseen its implementation. Made in USA Fraud: Khan’s FTC passed a rule banning fraudulently claiming a product is made in USA, the rule is still in effect. Subscription Traps: The Khan FTC proposed a ‘click to cancel’ rule that makes subscription traps illegal, though that set aside in court. It is unclear what the Trump administration is going to do. They did settle a consumer protection suit against Amazon for making it deceptively difficult to unsubscribe from Prime. It wasn’t a great settlement, but they did uphold the law. Lower Asthma/Epipen Prices on Ending ‘Orange Book’ Fraud: The FTC rolled back a form of patent fraud that allowed medical device makers to unlawfully extend patents, particularly in “asthma, diabetes, epinephrine autoinjector, and COPD drugs from prompt generic competition.” Prices in these markets are likely to fall quickly over the next few years. Civil enforcement Quadrupled: One of the key goals of the Biden administration antitrust enforcers was to reinvigorate private antitrust litigation, where either lawyers bring class action suits or represent individual injured parties. They accomplished this goal in two ways. First, they used the law and got judges to accept antitrust as legitimate, and they filed statements with the courts encouraging judges to interpret the law in ways friendlier to the public and less friendly to monopolists. And it has worked, with the amount of private litigation skyrocketing.

For instance, Michael Jordan is trying to restructure NASCAR, the realtor cartel is under attack, CureIS is seeking to reorient health records, and physical therapists and pharmacists are suing big insurers/middlemen. The most noticeable consequence is in college sports, with some athletes actually getting paid for what they do. And app stores are about to change.

So those are some of the major areas of improvement. What has worsened in terms of the law itself? I don’t mean enforcement policy, which we’ll get to, I mean the actual rules by which our society is supposed to be ordered. And there are some important setbacks. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau: Federal consumer protection around finance is mostly gone, and attempts to oversee big tech’s move into payments are over. It’s hard to overstate the importance here, most provisions against fraud, theft, deception, and unfair practices will now go unenforced by the Federal government among banks, credit bureaus, payday lenders, fintech, and crypto firms. Algorithmic Price Fixing: Last week, the Trump administration settled a case with alleged rent-fixing software firm RealPage. Immediately afterwards, the company sued to block a New York state law prohibiting price coordination, saying it’s a violation of the First Amendment. This one’s a rollback, and has policy implications on algorithmic price fixing across the economy. Monopolization Remedy Law: There are two parts to the law against monopolization. The first is whether a company is liable for monopolization, the second is what to do about it. While monopolization law itself is better, the remedy part is not. Judge Amit Mehta ruled that Google is an illegal monopolist (good), but also ruled that it’s too costly to actually remedy that monopoly (bad). That has the potential to corrupt the remedy process of the Sherman Act. Competition Executive Order: In 2021, the Biden administration created a competition council to encourage anti-monopoly work across the administration, and inside the White House. Trump withdrew it, and his economists are actively trying to meddle in the Antitrust Division’s work. Another rollback. Non-compete law: While the law is better than it was, the Trump FTC is trying to avoid appealing the decision setting aside the rule against noncompetes.

And now we get to the stuff that’s more recognizable, not the litigation nerd stuff but the actual big policy headlines that seem to affect our society. And here the news is mostly, though not entirely, bad. Facebook/Meta Dominates: Probably the most significant failure has been attempting to address the social media monopoly Facebook, which was found for years to have harmed children and fostered ethnic conflict worldwide. The scandals haven’t stopped; just over the past two weeks, it was sued over involvement in sex trafficking, and a story came out showing that up to 10% of its revenue allegedly comes from scam ads.

I wish I could say any of it mattered, but it has not. Mark Zuckerberg’s company is now a newly empowered macro-economic force, at the center of Trump’s data center-focused strategy. Trump even invited Meta’s chief technology officer, Andrew Bosworth, to become a lieutenant colonel in a new part of the Army dedicated to technology.

So what happened? In 2020, the Trump administration had an ‘anti-big tech’ framework. They filed an antitrust case, which the Biden administration continued, until finally last week Obama appointee James Boasberg ruled for the company. Boasberg decision was bad, but it was narrow and didn’t undermine monopolization law.

There are some policy rollbacks as well. The most significant is that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was regulating Meta’s advertising and financial activities; no longer. The Trump FTC may also roll back an important consumer protection move to stop Meta’s exploitation of kids. In 2018, the first Trump administration fined the company a token $5 billion for violating a consent decree with the government. The Biden FTC alleged Meta violated it once again, and attempted to harden the decree to block Meta from targeting kids with advertising, and forcing the company to get permission from the government before releasing new privacy-invasive features.

That case, however, is now stayed in court, after the Trump administration and Meta jointly asked the court for a 90 day stay to “potentially narrow and streamline any remaining issues.” Sounds ominous. On the other hand, the Trump FTC is asking for more rules around children’s privacy and is looking into Meta chatbots that talk to children. Still, it’s hard to see the antitrust loss, plus the centering of Zuckerberg’s firm as a national security asset, as anything but a huge loss.

Google Becomes a $4 Trillion Monopoly: While Google’s legal journey is a bit more complex than Meta’s, this one is a big loss, at least for now. The anti-monopoly movement threw everything they had at Google, from Congressional investigations in 2019-2020 to reports and advoacy. In 2020, the Trump DOJ brought an antitrust case on narrow grounds over its distribution choices, notably that it bought up all the shelf space for search engines. Biden antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter oversaw that litigation, and brought another set of claims related to the company’s adtech monopoly.

Judge Amit Mehta ruled against the company in 2024 for illegal monopolization, and Judge Leone Brinkema did the same for its adtech. Those two decisions, plus the Epic Games decision, should have been enough. Unfortunately, new Trump nominee Gail Slater failed to keep a tight hold on the litigation team, and Mehta let the company off the hook in September, ruling that Google’s illegal payments to Apple were too important to the economy to stop. We’ll see if she appeals. Brinkema has yet to put forward her remedy decision, but seems cautious. And as with Meta, the Trump CFPB has stopped looking into Google’s role in payments.

The consequences so far are very bad. Immediately after Mehta let Google escape, the company reconstituted its monopolization techniques in the generative AI space, taking the lead with its trove of data, distribution, and cash, as well as its vertically integrated from cloud-to-chips-to-search data framework. The Financial Times called the company “a near-$4tn monument to monopoly power,” though that understates the problem. If all the cases had gone perfectly, Google still had immense power in maps, video, email, et al.

But now Google and Meta are now too big for democracy. App Stores: Here’s some good news. App stores have been revamped pretty substantially. In 2020, Epic Games kicked off the civil war in American business, suing Google and Apple over their control of mobile app stores. The government filed statements of interest in the case, and the Antitrust Division also launched its own case against Apple in 2024, which is pending.

The net result is that app developers can now avoid some of Apple’s fees and strict control of iPhone. Meanwhile, Google has said it will slash fees from 30% to 9% for app developers. Both the Apple and Google arrangements are being reviewed by judges, and are likely to be reorganized. The Trump Merger Boom: Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter angered Wall Street from the get-go, blocking bad mergers and protecting industries like books, groceries, and semiconductors. Nvidia, the most valuable company in the world, was saved from itself by Khan, who didn’t let it buy ARM. That era is over, and we’re in a new tremendous consolidation phase.

While the legal precedents won by the Biden administration haven’t been reversed, the Trump administration is at historic lows in terms of enforcing the Clayton Act. The Antitrust Division hasn’t tried to block a single merger, waiving through bad deals like Hewlett-Juniper/ Capital One-Discover, Disney/Fubo and Google-Wiz. The FTC has challenged two small mergers, losing one trial, and is in the midst of another, though it too has allowed bad deals, like IPG/Omnicom The Union Pacific-Norfolk Southern merger, though in the rail space, will be historically dangerous.

But the pro-monopoly approach is almost less worrisome than the open corruption in the process, whereby MAGA lobbyists have been able to extract fees and Trump has been able to get political concessions in return for allowing consolidation. Stephen Colbert was fired likely as part of a merger process, CBS news was revamped along right-friendly lines, and Jimmy Kimmel was nearly fired. These changes aren’t that important in and of themselves, but they are fusing Trump’s political interests with those of dominant firms. Amazon: Amazon hasn’t benefitted as much in the AI-centric Trump strategy as other firms, though it is part of it. The antitrust case, filed in the Biden era over the company’s use of its market dominance to raise prices, continues under Trump. Trump’s FTC, by contrast, settled a consumer protection suit against Amazon for making it deceptively difficult to unsubscribe from Prime. Apple: Aside from Epic Games prying open the company’s app store, the Antitrust Division filed an antitrust lawsuit against Apple in 2024, with a pretty expansive ‘ecosystem’ analysis of the company’s market power. The suit is ongoing.

So there we go. There are a lot more cases I didn’t go over, but those were the main legal areas. (A full list is here.) As you can see, much of the legal edifice established over the Biden era remains, and some is being used by the Trump officials, private lawyers, and state enforcers, who are newly emboldened. Moreover, thousands of lawyers have been trained in antitrust law, and the concept of market competition as a meaningful part of policy is part of public discourse, and likely to be embedded in the 2028 Presidential campaigns. There’s a lot more to say about the Biden to Trump shift, and what it means. We should not obscure the ugliness of the current approach to market power, if for no other reason than the public is bearing witness to the true fusion of monopolies and the state. But in terms of the narrow question. Is populist antitrust over? No. Not by a longshot. There’s no putting the toothpaste back in the tube. And now the news of the week. A major monopolization trial between Michael Jordan and NASCAR starts tomorrow, and it’s going to get ugly. Plus James Cameron goes after Netflix, there’s now an AI-enabled accidentally psychotic teddy bear, Medicare Advantage fraud starts hitting politically influential senior groups, and Trump is thwarted in his attempt to fire the Librarian of Congress, which has implications around AI. Oh, and private equity giants screwed up portable toilets. Read on for more... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app | |