How NBA Legend Michael Jordan Is Blowing Up NASCAR's MonopolyThe France family has run stock car racing since NASCAR's founding in 1948, treating team owners like high-end Uber drivers. Now an antitrust lawsuit brought by Michael Jordan could upend NASCAR.“The France family and NASCAR are monopolistic bullies. And bullies will continue to impose their will to hurt others until their targets stand up and refuse to be victims. That moment has now arrived.” - complaint against NASCAR On Monday in a Charlotte, North Carolina courthouse, the weirdest and most interesting monopolization trial of the year started. A driving team, 23XI Racing, is suing NASCAR over its control of the sport, alleging violations of the Sherman Act for acting as a monopolist in the premier stock car racing market. 23XI is owned by basketball legend Michael Jordan and three-time Daytona 500 winner Denny Hamlin. Sitting on the other side is the billionaire France family, which owns NASCAR and speedways across the country. It’s a real North Carolina scene, which is full of race tracks and racing fans. Jordan is a strategic weapon, sitting in the courtroom every day as the most famous and accomplished athlete in the history of the state. He is famously apolitical, but in this case, he said, “I’m willing to fight for a competitive market where everyone wins.” Several jurors were dismissed because of their love for Jordan, whereas another was kicked off the case because of her dislike for one of the driving teams involved. And then there was the guy who joked on his juror form that his hobby is “heavy drinking;” he was ultimately chosen to serve. The judge, Kenneth Bell, is a Trump appointee, and he moved the case lightning fast, bringing it to trial in a year. The world of racing fans is glued to the trial, just as authors and agents couldn’t get enough of the merger challenge to Penguin/Simon & Schuster. And the reason is that antitrust trials are where everyone learns how their industry really works. There had always been rumors of dictatorial controlling behavior from NASCAR’s leadership, as well as attempts to quell dissent, everything from criticism of fees to attempts to unionize drivers. But now the evidence is coming out. For instance, a few years ago Richard Childress, a legendary former driver and current owner who won six championships with Dale Earnhardt, made a comment about a new NASCAR TV deal. “Childress needs to be taken out back and flogged,” NASCAR Commissioner Steve Phelps texted Chief Media Officer Brian Herbst. “He’s a stupid redneck who owes his entire fortune to NASCAR.” Drivers and writers are in shock over these comments towards someone considered royalty in the sport. Another NASCAR stakeholder at one point showed contempt for fans, texting in one exchange, “Unfortunately, most our fans are not exactly top readers.” The bad behavior is downstream from the market power exhibited by NASCAR. Last year, I wrote up the allegation of how the corporation maintains its monopoly.

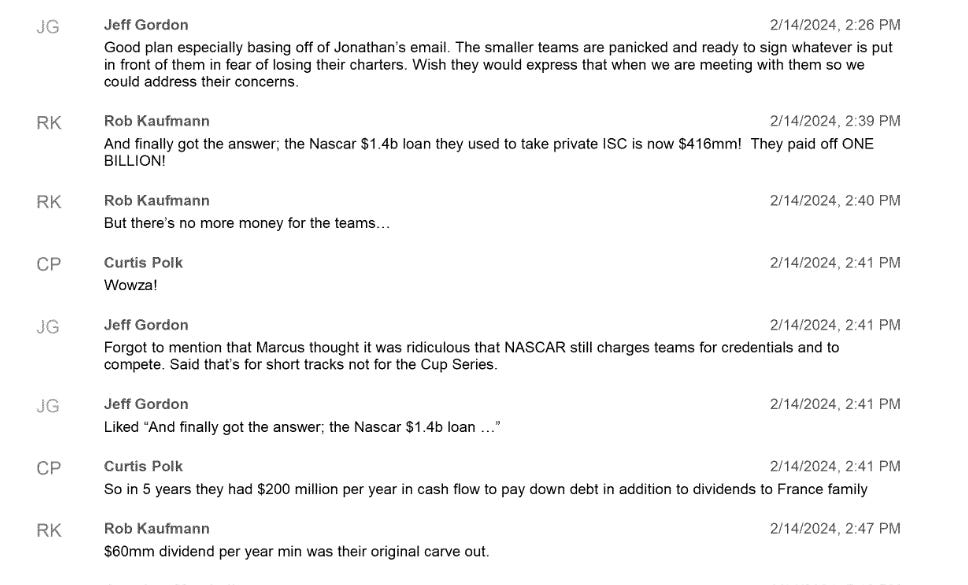

Formally titled the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, NASCAR is a sanctioning body and operating company that offers temporary franchises to teams who own and run racing cars. It negotiates and splits TV revenue with those teams, runs marketing, owns racetracks, sets the rules, and otherwise manages the sport. It was founded in 1948 by Bill France, Sr., and the France family still runs it today. A charter guarantees a spot for a team in NASCAR races, and some of the prize money. Yet charters aren’t permanent, but must be renewed by NASCAR, which can revoke them. Unlike major sports like the NBA or NFL, NASCAR shares relatively little with its teams, not nearly enough to cover the actual costs of running race cars, such as paying superstar drivers millions of dollars. Teams have to make up to cover these expenses with sponsorships, but NASCAR itself sometimes competes for those same sponsors. It’s a tense relationship, and teams are often on the verge of bankruptcy. According to the plaintiffs, 19 owners had charters in 2016, just eight remain in the sport. One left the sport a year after winning the championship. In going through some of the court documents, what I found was the antitrust suit was the final straw in a long-running saga. Teams had been trying to collectively bargain for better terms for years, but were operating in fear over retaliation from the France family. As this discussion between NASCAR legend Jeff Gordon and financier Rob Kaufmann shows, weaker teams were so terrified in negotiations they would “sign whatever is put in front of them” for fear NASCAR would eliminate their charters. Meanwhile, NASCAR had $200 million in annual cash flow for dividends and debt payments. In 2024, Jordan and Hamlin had enough of what they perceived as coercion from NASCAR, and worked with antitrust lawyer Jeffrey Kessler to file suit. Kessler is best known for breaking the NCAA cartel in 2020 over allowing college athletes to earn sponsorship money; he’s a heavy hitter. For its part, NASCAR has hired big law partner Chris Yates from Latham & Watkins. NASCAR’s response is that there is plenty of competition among motor sports, from IndyCar to NASCAR to Formula 1. They compete over capital, talent, and sponsors. Moreover, the monopolization claims from two owners are pretextual, a mere way to extract better terms they couldn’t otherwise get through skill or value creation. Owners requested the charter system now at issue, and did not discuss trying to race in other stock car racing circuits. Moreover, their franchises, though temporary, are worth money, so there’s economic value that these owners are pretending doesn’t exist in order to put forward a claim. But Yates also made a significant legal error that makes the case easier for the plaintiffs. As part of the legal tussle, NASCAR countersued the teams, alleging that the owners were themselves violating antitrust law by coming together as a cartel in joint negotiations. In bringing that claim, NASCAR unwittingly told the judge it’s a monopolist in the premier stock car racing market. And so while the judge dismissed NASCAR’s counterclaim that there’s an owner cartel, he did rule that NASCAR is a monopolist. “NASCAR made a strategic decision in asserting its Counterclaim and must now live with the consequences,” the judge wrote. Oops. The case is going badly for NASCAR. Yesterday, Hamlin got emotional on the stand, crying when he discussed entering the sport and telling the jury about his views of NASCAR’s unfair terms. “If the terms were fair, (so many teams) wouldn’t have gone out of business,” he said. “Only one side is going out of business.” Today, NASCAR’s lawyers sought to take apart Hamlin’s credibility, attempting to show him as a spendthrift and unreliable narrator changing his story to whatever would best suit his needs. But then the plaintiff’s lawyer, Jim Kessler, put NASCAR executive Scott Prime on the stand. And Prime had to defend his own emails saying NASCAR prevented Speedway Motorsports from hosting a different stock car series, the Superstar Racing Experience (SRX), over fears that SRX might become a real competitor. There are eight more days to go, and the seething anger and evidence is going to continue emerging. As with all antitrust cases, the outcome is uncertain, and it’ll likely be appealed on various grounds. But already, NASCAR’s reputation, and that of the France family, has taken a serious hit. The company has always been known as a dictatorship. In the 1960s, Bill France Sr. banned union members from participating in races. “I’ll use a pistol to enforce” the rule, he said. “I have a pistol and know how to use it.” There were physical fights over safety matters at tracks. But under Bill Sr, NASCAR was well-managed. But the big problem is that the stock car series has lost its mojo. In 2004, 17 out of the top 20 biggest sporting events by attendance in the U.S. were NASCAR races. At roughly that time, comedian Adam McKay released the beloved comedy, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, starring Will Ferrell and John C. Reilly in a story about NASCAR drivers in George W. Bush’s America. It was the number one movie at the summer box office for two weeks in a row, and captured the zeitgeist of a sport that was then at its zenith. Dale Earnhardt Jr. was one of the most popular figures in the country, and NASCAR was at a peak in its popularity. From 2001-2015, average viewership was 15-19 million. But that has changed. Last year the Dayton 500 had an average audience of 6.7 million. Attendance and ratings have collapsed, and races, which once sold out tickets and were the biggest sporting events in the country, now routinely have empty stands. While always right-leaning, the league got more political, with CEO Brian France, the grandson of the founder, as an early Trump supporter. Then in 2018, France was arrested for drunk driving and possession of oxycontin. Yet, NASCAR maintained tight control of its media image, so it was hard to figure out what had gone wrong. NASCAR fans are finally finding in this lawsuit some of the answers to why the sport hasn’t been managed well. It’s because the management, while always dictatorial, came to have contempt for the actual teams and fans who made the sport work. And that’s where this antitrust suit could actually help. Michael Jordan, in some ways, is the ultimate fan. He loves racing, and the competition, and put his money to work to win championships. And his group is angry that NASCAR doesn’t seem to take the sport as seriously as they do, instead choosing to focus on extraction. There are many important aspects of this case. It’s a monopolization argument that may lead to NASCAR having to sell some of its tracks, aka a break-up. It is on trial within a year, which shows these cases can be done quickly. It’s a jury trial. But if nothing else, it is actually forcing some accountability for the billionaires who own NASCAR, purely through the court system. And in doing so, it is showing the potential of a path for others who don’t want to take crap from bad leaders anymore. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |