|

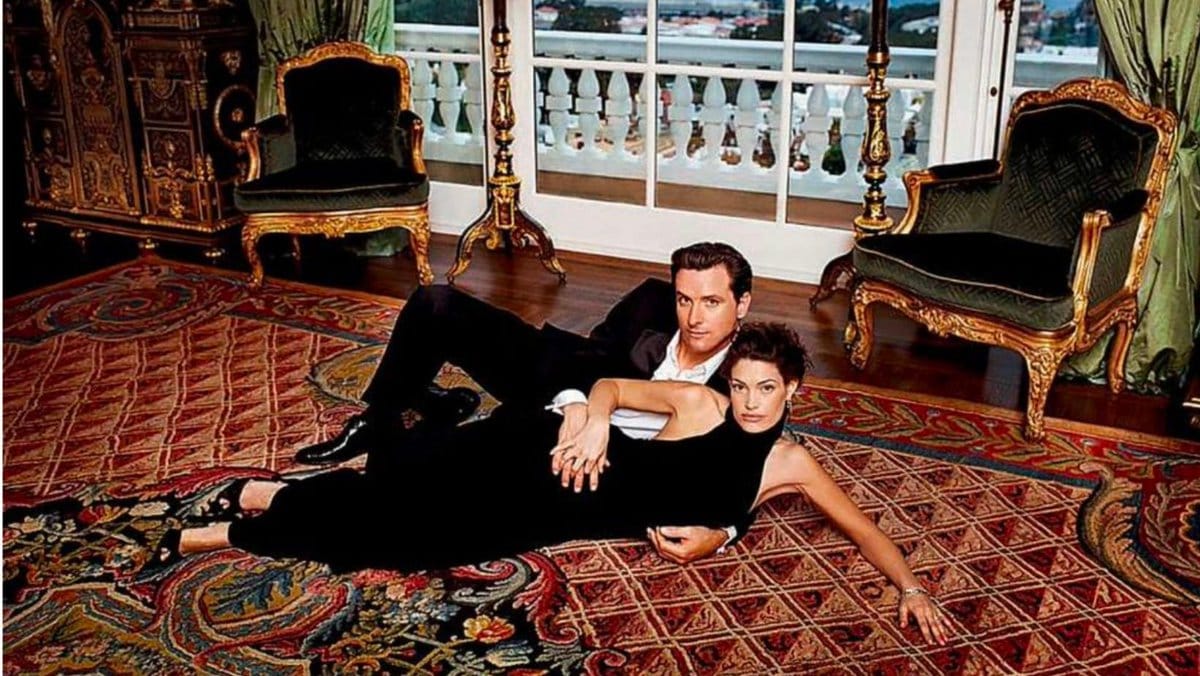

How do we deal with a culture of abuse? What is our part in ending it? How do we deal with an abusive cult of millions? Man, I don't know. Lately it’s hard to know where even to start or where to begin. Do I have to list all the news stories? Either you’re aware or you aren’t. Many aren’t. I don’t know what to do with that fact, but it seems like a choice, though an understandable one. Awareness carries a high cost these days. It’s exhausting. It’s meant to be exhausting, I think. This is how supremacy works. The costs of reparation are very high, and the cost of awareness comes first of all. To sum up: The Republican White House, including the president and his cabinet, is regularly engaging in open white supremacist and neo Nazi rhetoric from official and unofficial channels, in service of their racist ethnic cleansing program, their unconstitutional crimes against humanity both domestic and foreign, their demolition of our modern society, of our scientific progress, and our democracy, their punitive acts of war against the civilian population of the United States and civilian populations abroad, and an almost unfathomable level of self-enriching corruption—and the elected leaders of Republican Party and the bribed fascist Republican supreme court, which could have stopped any of this at any time, is largely accelerating it. There is a general corrosive attack on any notion of kindness, of dignity, of competence, of knowledge, of diversity, and of truth. Yes, tens of millions of people—neighbors, members of our own communities, often members of our own family— are not only OK with all this, but in favor of it, some of them violently so. Some rather pathetically plead ignorance to what it is they’re supporting. Some make excuses, which involves ignoring large swaths of reality, and fabricating intricate lies and rationales to defend themselves from confronting what it is they support or enable. Others are proudly in favor, and brag and laugh the more distressingly cruel everything becomes, as a demonstration of their license to enact their cowardly bullying; use our distress as an object of fun as a way of demonstrating their license to enjoy suffering; tell distressingly obvious lies to demonstrate their license to tell lies about observable reality. This critique of Republicans is not meant to suggest that Democrats are distinguishing themselves in matters of courage. Lead Democratic capitulator Hakeem Jeffries unveiled a new campaign slogan, sourced from a venture capitalist’s book; it is, and I swear I'm not making this up, “Strong Floor, No Ceiling.” It’s the sort of thing that seems designed to inspire nobody and promise nothing, which is certainly seems to be the vibe Democratic leadership is after. Meanwhile, prominent presidential hopeful, California governor Gavin Newsom, a man who has made a habit of neglecting and harming marginalized people groups as a matter of rhetoric and policy, recently prefaced some salutary comments about progressive tax policy and wealth redistribution with a call for his party to be “less judgmental,” which is OK insofar as that goes, but also “more culturally normal,” which accepts the supremacist Republican framing of what is “normal” to such a degree that Newsom's “less judgmental” seems to signify a desire for us all to stop exercising any moral judgment whatsoever, and frankly I hope he gets the sugar shits all over his apartment.  Mr. Culturally Normal himself We were told our institutions were built to prevent this. That was the story. They aren’t doing what they were built for, if that is the case; they’re mostly abetting it. Over the last ten or fifteen years, many of us have learned what many others already knew their whole lives: That our systems and institutions largely serve to promote and defend supremacy of wealth, of certain religions, of certain races and sexual orientations and gender identities, of maleness, of the able-bodied and employed and employable people. I think that means that they serve to promote and defend abuse, mediated through largely unacknowledged trauma. I see all the suffering and menace and hatred; the increasing comfort with excluding and immiserating and killing others and the celebration of the exclusion and suffering and death of others. And again, at the root of it, tens of millions of people—neighbors, members of our own communities, often members of our own family—are in support of it, or else willing to enable others’ support of abuses, to different degrees and for different reasons. And there are some who find the different degrees of support and the reasons provided for this support very interesting, or anyway more interesting than I find them. What I notice is that most supporters of this abuse manage to find a way to justify continuance of that support no matter what happens, exhibiting a behavior and belief pattern not incorrectly compared to a cult. And when a cult reaches a critical mass, to such a degree that it involves tens upon tens of millions of people, and informs societal beliefs and permissions, and captures the political apparatus, I would argue that the cult has become culture. So I would say we are dealing with a cult of abuse, but also a culture of abuse. And this suggests to me that we live in an abuse-oriented society. So, like I say, it’s hard to know where even to start or begin. There are some who see people's support of our culture of abuse as more of an output from this context of unacknowledged trauma and untreated mental health, of technologies and propaganda socially engineered to trigger fear responses, and other social factors which make our neighbors' and family members’ support and enablement of abuses almost totally inevitable. And I must say, this societal context certainly does exist and it is unquestionably relevant to why so so many people engage in such destructive and distressing and abusive behavior. However, others (and I am one of these) notice that many millions of others live in the same abusive context with similar trauma, and struggle with the same predatory technologies and propagandas and mental health challenges, yet still manage to not support this abuse, and so we see support of abuse as less of inevitability we see instead some agency and choice at play. Whatever the degrees or reasons or context or level, the abuses that are happening are alarming and disgusting and shameful things for any person to enact or to support or to enable, and so I am alarmed and disgusted and ashamed to find I live in a society so willing to enact and support and enable them, and ashamed of such people who participate, and ashamed of myself to the degree to which I do so—and so, I imagine, are many of you. These are things that I find unacceptable, and so I refuse to accept them—and so, I imagine, do many of you. I don't think it would be incorrect to call this sort of behavior and the urge to support and enable it evil—or anyway, if it isn't to be thought of as evil, it could only meant that evil doesn't have any use as a category. If you are reading this, I presume that you think having our society and politics dominated by a cult of supremacist abuse is all not ideal. I presume you’d like to see things get better. I presume you'd like to see the cult lose its institutional and cultural power, and consequence come to those most responsible. I presume you'd like to see those in the cult stop being in the cult. How does a culture of abuse end? What is our part in ending it? This is what I’ve been thinking about lately, a lot. This all goes so deep that I feel as if every sentence of the above might become an essay of its own. I suspect I’ll be writing about different facets of this subject, well into 2026. Quick interruption time. The Reframe is me, A.R. Moxon, an independent writer. Some readers voluntarily support my work with a paid subscription. They pay what they want—as little as $1/month, which is more than the nothing they have to pay. It really helps. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of my upcoming book. There exist a whole spectrum of philosophies about how to end a culture of abuse, and a whole spectrum of philosophies of what our part in this effort should be. There are those who seem to believe we have no responsibility to one another whatsoever, and therefore no responsibility whatsoever toward those lost to the cult of abuse. There are others who seem to believe that those lost to the cult have little to no agency, and it is entirely the responsibility of others to change their minds, to offer them some form of redemption. Some even seem to believe that it is everyone else's job to redeem members of a cult of abuse on their behalf. These are extremes, of course, and simplifications, but as I say, it is a spectrum. Some people will tell you that the only thing that will ever work to end a culture of supremacist abuse is violent confrontation of abuse’s violence. This may alarm you. As somebody who tries not to be violence-oriented, it alarms me. However, it’s historically true that some of our greatest progressive changes away from our supremacist culture have been effected in this way, and it’s true that sometimes when an abusive person or culture’s margins of permission have been enabled far enough toward abuse, violence becomes inevitable because violence has already arrived. It can sometimes get that far. Still, I dare hope to decrease violence where it can be decreased, and to avoid it where avoidance is possible. The lesson I’d rather take is not the inevitability of violent confrontation, but the importance of not enabling abusive people and institutions to the point where violence is needed to end their abuses. Some will tell you that what’s needed is to establish (or re-establish) social penalties for abuse and for support and enablement of abuse. I’m somebody who feels that way, in fact, and have written extensively in favor of this philosophy. Others, meanwhile, point out that social isolation encourages indoctrination into cults, and I must admit that there is appears to be true, so there appear to be complexities to navigate, or at least to ponder, and I intend to do so as we go. Some people believe that what will end the cult of abuse are institutional reformations, using our institutions as tools or reshaping them into other tools—the idea being that if we elect the right people and pass the right laws or enact the right form of government, we can start to address trauma, repair what is broken, and make space to bring people into right alignment with their own humanity again. And it’s observably true that in the past institutional reformation has attended progressive change. However, I'm also aware that people of abuse will use any tool toward abusive ends, so it seems to me that changing our tools will only go so far without a change to fundamental assumptions about how tools are permitted to be used, and toward what ends. Some believe that natural consequence will eventually turn people to the light. It’s not wrong to say that supremacist abuse carries natural consequences, because supremacy is a machine built on unsustainable lies in order to eat people, and unsustainable things don’t sustain, while a machine built to eat people will eventually eat you if you are a person. And this does occur sometimes. Our temporary president's approval rating is in the 30s, which is not great as approval ratings go. On the other hand, that means over 30% of people still approve, even now. It would appear that some people are resistant to consequence unto death, which is indeed something we know about cults. Some believe that what is needed is to persuade others to our side, with logic and inveiglements and appeals to their humanity or their "better angels." Some even want to employ what I’ll call the Ezra Klein method, which is to say, if you can’t beat them, join them—or, more accurately, if you can’t even be bother to start trying to beat them, join them. Here the idea is not so much to appeal to their better angels but simply tell them that their worse angels are just fine with us, and let's all pretend we're good angels together. Some of these philosophies resonate with me more than others, but even those to which I feel most attuned have their pitfalls and weaknesses, while even those I find weakest might have their uses. (I struggle to find any good use for the Ezra Klein method, but maybe someday I’ll see one. Stay tuned!) And I have frustrations with all these philosophies to greater or lesser degrees. I’m pretty skeptical about the uses of persuasion, for example—or at least with persuasion as it is generally understood and practiced. And I'm fairly frustrated at our seeming obsession with redeeming people who show no interest in redemption. Yet at the same time, if somebody in our culture of abuse is persuaded to leave our culture of abuse, I would do badly to let my frustrations and skepticisms about the method’s efficacy interfere with that persuasion. If somebody truly would reclaim the humanity they have abandoned, I would do badly to deny the reclamation. Here’s what I want to note: all of these philosophies involve redrawing the boundaries of what is and isn’t acceptable. All of them involve some way of defining what the costs of society—and there are always costs to a society—should be, and how they should be configured. So I think that’s what I’ve been pondering. To answer the question “How does a cult of abuse end, and what is our part in ending it?” I ask “What should our boundaries be, and how should we redraw them?” Let’s start with abuse. What it is, what it does, how it works. Or don't subscribe. I'm not the boss of you. But if you do subscribe, you get one of these essays pretty much every week. Let me define abuse as “power used in an inappropriate way.” You do something that hurts somebody else because you have the power to do so, and you see some advantage to yourself. An institution hurts people because it has the power to do so, and it sees some advantage for others who perpetuate it. Abuse, then, causes harm. There is power inherent in it, which means that any investigation into abuse must consider the power dynamics involved. There is violence inherent in it, which may be physical, psychological, personal, or institutional, which means that any investigation into abuse must consider who is harmed, and who is harming.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

Say I tell you “My father is choking my brother.” What do you say to that? I’d say that’s an act of abuse, wouldn’t you? My father is choking my brother because he has the power to do so. My brother is paying the cost, and the cost is the damage from the attack, or even the loss of his life, or the trauma after the fact of an attack, or even an attempt on his life. Abuse, then, appears to be an act. It appears to have a cost of harm. We might call that cost “trauma.”

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

Say I tell you “My father is choking my brother because he was himself choked by his own father.” You’d likely be able to believe it. There are many such cases. Those who abuse tend to abuse. Those who suffer trauma tend to traumatize. My father has been given a cost, and he has passed it along. You might still note that my father, while abused once, is not being abused now. Abuse, then, appears to be a continuum. An act that leads to an act. A passing along of cost. A generational inheritance of trauma.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

Say I tell you, “My father is choking my brother because he learned that he can harm his children without consequence, because his children are seen as his property to control, and abuse is deemed an acceptable or even necessary response to any infraction.” I think you’d believe this, too. Our culture does indeed move to defend abusive people from damage to their fortune or position or reputation. Our culture does see abuse as natural in many ways. Abuse, then, appears to not only be an individual act and an individual continuum, but a collective one. A cultural context and a societal permission structure.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

Say I tell you, “My father also chokes me, though not as often as he chokes my youngest brother. He never chokes my oldest brother.” Abuse, then, appears to involve preference. There is at least the preference of the abuser over the abused. There is also the preference for abusing one person more than another person. And this does appear to be a choice. Say I tell you, “I, however, do not choke my children for any reason. I believe it is wrong to choke your children.” Abuse then, appears to be a cycle that can be broken. The trauma doesn’t have to be passed on. Another choice appears. So you might observe that abuse involves choice.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

Say I tell you, “I have a responsibility to my father, to convince him that violence is not appropriate or acceptable.” I think you’d probably agree that there is some sense to that. It would certainly be better if my father stops choking people. If there is a person who can help my father make that choice, they probably have some responsibility to do so, and the more influence they have over my father, the more the responsibility. Say I tell you, “One way that I can convince my father that abuse is not appropriate is to heal his trauma.” I think you’d probably agree that there is some sense to that. My father very likely has some trauma, and it would be better if my father’s trauma were healed. If there is a person who can help my father heal, they probably have some responsibility to do so, and the more influence they have over my father, the more the responsibility. And you might agree with this, but still notice that my father is a person, and nobody has more influence over him than himself. If I said all of these things to you, I think you could truthfully say that I am aligning myself in meaningful and necessary ways against abuse, and not for it. Abuse, then, appears to also be not only an act and a continuum, but an alignment in relation to an abusive act and those who commit it; an alignment to an abusive system and those who enable it.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

What if you pointed out to me that I have spent all my time talking about the perspective of my father, who is choking my brother to death, but haven’t said anything about the perspective of my brother, who is being choked? What if you pointed out that I had spoken only about my responsibility to my father, and nothing of my responsibility to my brother? What if, after you pointed this out, I kept talking exclusively about my father’s perspective, and my responsibilities toward him and his traumas? You might then start to see that, even though I have aligned myself against abuse in meaningful and important ways, in other ways of which I might not even be aware, I still remain aligned toward the abuser, not the abused. Abuse, then, appears to be not only an alignment relative to the person enacting abuse, but relative to the person receiving abuse.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

And what if you were to remonstrate with me about all this, and I were to remonstrate back, each of us talking about what is to be done, and what is the best method for persuading my father to abandon abuse and heal. Meanwhile, the whole time we’ve been talking over what do about my father, my father has been choking my brother, and my brother is now dead. Abuse, then, appears to be a responsibility that involves priority and immediacy. The greater responsibility appears to be to the person receiving the abuse right now. The greater priority appears to be attention to the abuse being done right now.

⚬──────────✧──────────⚬

Enough. Time for conclusions, and a question for next time. My conclusion is that when abuse is present and ongoing, it is the present abuse that we deal with first and most immediately, and our first responsibility involves not talk but action. There is the trauma of abuse that occurred in the past, and we'd do well to foster attitudes and create structures and institutions that facilitate healing. There is the future abuse that may yet occur, and we'd do well to foster attitudes and create structures and institutions that make that future abuse difficult and unlikely. But if we are to hope to engage in these things, our empathy and advocacy and activity must go first to today's victim of abuse. I think of my frustrations with the national dialogue around healing the traumas of those who have fallen into our culture's cult of abuse, and I locate it here, in wrong priorities, in our culture's eternal perseveration toward putting those engaged in abuse at the center of any question of healing, which is exactly where they demand to be placed. And so, even as we align ourselves with healing, we choose our alignment toward abuse. They are still in charge, this cult of abuse. They are still in power. They are consolidating. And still, most of all, our culture's concern is how to work out their redemption, their salvation, their return to a humanity we never took from them, but which they have abandoned, the better to deny that of all others. But our father's fingers are still on our brother's neck. Our first responsibility must be to stopping the abuse that is happening now. Here's the question that follows, the one I'm most often asked: How to stop the abuse that is occurring without falling into patterns of abuse ourselves? The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor for as little as $1/month. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish. Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe? Venmo is here and Paypal is here. A.R. Moxon is the author of the novel The Revisionaries and the essay collection Very Fine People, which are available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. But that's nothing compared to the bone-crunching action he'll deliver every Sunday on ESPN—Bears vs. Packers, catch it!

|