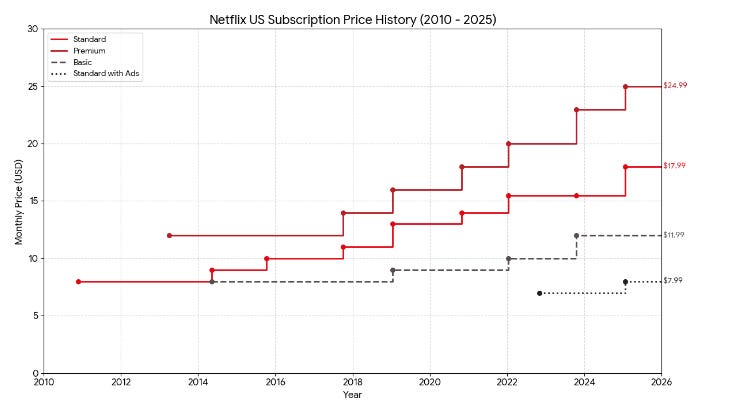

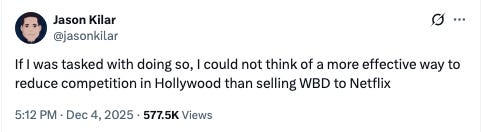

Monopoly Round-Up: Netflix Prices Have Gone Up 125% Since 2014Today, Donald Trump said the Netflix-Warner merger "could be a problem." Does Netflix even want to close the deal? Plus, the NASCAR antitrust case continues, and cowboys are very mad at meatpackers.The monopoly round-up is out, and there’s lots of news, as usual. Judge Mehta came out with the final detailed order on the Google search monopolization trial, Michael Jordan thinks he’s going to be beat the NASCAR monopoly, and Larry Summers has been kicked out of the economics fraternity. But this week, the big news is all about Hollywood. On Friday, Netflix announced its $83 billion acquisition of much of Warner Bros Discovery, a deal that combines the top paid streamer and the number three streamer, by subscriber count. There are many ways to see this deal, but the starting point has to be how angry the public was when it was announced. I was surprised to see an endless series of viral comments on social media mocking Netflix’s pricing and disrespect of movies. For instance: If there’s one fact to explain why people are so unhappy, it’s that Netflix subscription prices have gone up 125% since 2014, which is four times the overall rate of inflation. Americans think Netflix is greedy, and that it has exploited its market power to raise prices. Here’s a chart I put together showing the different tiers of service and the pricing changes. It’s not lost on people that the increased prices have turned Netflix’s founder into a billionaire, and that if the deal goes through, current Discovery CEO David Zaslav will get such a big payday that he’ll become a billionaire as well. And prices are likely to continue to go up. Why? Well, as the Entertainment Strategy Guy notes, “this deal needs to boost Netflix’s cash flow by $8 billion per year for the next 20 years to justify itself. That’s a lot of extra money to make from an acquisition.” The best way to increase cash flow is to keep increasing prices. On Friday, I went on CNBC on Friday to explain why the deal is bad, and why Warner should remain independent. I also had a longer conversation with The Ankler’s Richard Rushfield and former FTC Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya on the topic. The more I dig into it, the weirder the deal seems. Does Netflix Even Want to Close the Deal?There are a few unusual aspects to this transaction. The first is something that is important to note upfront - as Nick LoPiccolo of the Hollywood Reporter observed, Netflix may not care that much if it is actually able to finalize the deal. Controversial mergers take between 18-24 months to close, and in that time period, the company being bought is paralyzed. And that means Netflix gets to freeze important rival - Warner’s HBO Max - for the next couple of years, regardless of what happens. Think about it this way, if someone is pitching a movie or TV show to Warner and Netflix as this deal is pending, who are they likely to choose? There are a few other advantages. For the time this deal is pending, Netflix also blocks another rival, Paramount, from buying Warner, giving it more of an opportunity to cement its lead in streaming. There’s another big advantage of the bid for Netflix, which is that it will get access to competitively sensitive information about a significant rival. The counter to this point is that Netflix will have to pay a big break-up fee, $5.8 billion or 7% of the size of the deal, if it doesn’t go through. And in the merger documents, it has pledged aggressively to litigate this one, including through any and all appeals. Still, $5.8 billion in the context of an $82 billion deal is not that much. For a frame of reference, Google offered a $3.2 billion break-up fee to Wiz for a much smaller $32 billion transaction, which is a 10% fee. An Unpopular DealThe second odd part of this proposed deal is that the business and trade press did not immediately take the side of the merging parties. It’s almost always the case that the media cheers for consolidation, or at least says it’s inevitable. Yet that didn’t happen in this case. Here, for instance, is the Wall Street Journal’s headline on Friday. And the industry press is also skeptical, at least for now. The chief film critic for Variety, Owen Gleiberman, attacked the combination, saying “It is hard, at this moment, to resist the suspicion that the ultimate reason Netflix is buying Warner Bros. is to eliminate the competition.” The Hollywood press never opposes mergers, they love deals. But not this time. Why is that? Well, this deal isn’t a normal “make a quick buck” fling, it’s existential for the industry, because it will kill the major experience of seeing a film. While a lot of people think that movie theaters are dying, in fact that’s not true; a bunch of youth-oriented movies are actually starting to draw kids back to the movie theater. However, if Netflix does buy Warner and limits theatrical releases the way people expect, it will be game over. “I spoke with a major executive in theatrical exhibition,” said Ben Steinberg. “They said to expect North America to lose 5 thousand screens under a Netflix controlled WB within 5 years.” Other major studios, especially Paramount, which is owned by Oracle founder Larry Ellison, are in a dangerous position. If Netflix gets the deal through and does kill theatrical exhibitions, smaller studios will have enormous trouble competing in the entertainment business. In other words, there’s a reasonable chance the movie industry will basically end after this deal. And it’s not just me saying that, the New York Times just published an op-ed by the former head of Amazon Studios saying that this combo “will be the end of Hollywood.” Another unusual part of this deal is unlike most debates over business law, this attempted purchase broke into the mainstream. Americans have very strong views about TV and movies, because Hollywood is our cultural lingua franca. Netflix has 80 million subscribers, and Americans watch it. It’s a brand as big as Walmart or Coke, and like MTV in the 1980s, it’s almost necessary to have it to participate in cultural conversations. So normal people have thoughts, as do politicians. “The Netflix-Warner deal is a horror movie,” said former FTC Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya. Actor Ben Stiller got into arguments online about why the deal is bad, Senator Mike Lee promised a Congressional hearing, Bernie Sanders called it another example of ‘oligarch control,’ Silicon Valley would-be superrich mused on the virtues of “creative destruction,” and Lina Khan’s name trended on Twitter, simply due to people tweeting about how they wish she were in office to block the deal. Here’s Senate candidate Graham Platner: A Bidding War Full of Illegal BidsAnd the final odd discussion point is that the Netflix acquisition was the outcome of a bidding war in which all three bidders made illegal offers. Comcast, Paramount, and Netflix all sought to buy Warner, and all three proposals would have consolidated the industry in ways that look like a violation of antitrust law. Yet this dynamic creates an odd discourse, where people are weighing one acquirer against another, as if the choice is which illegal deal to accept. As Senator Chris Murphy noted, that’s fundamentally a toxic way of thinking about the problem, forcing us to imagine which deal is relatively less corrupt. That, however, is not how the law works, or at least not how it should work. If all three deals are illegal, then none of them should happen. Warner has positive free cash flow, it is perfectly viable without a buyer, so it can stay independent. Consolidation, in other words, is not inevitable, and it’s not even legal. That’s not to say that any imaginable deal is unlawful, it’s fine if someone who isn’t an existing powerful player comes up with the cash to buy Warner and run it as a viable studio. Is the Deal Legal?The question of whether Netflix will be allowed to buy Warner has a few parts. The first is the law. As former Biden Antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter noted on CNBC, this deal looks pretty sketchy. And it’s not just Kanter, here’s Jason Kilar, the former CEO of Warner Media. The relevant doctrine here is the Clayton Act, which bars combinations that “may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” To see whether this deal violates that law, we have to start with the markets in which the two firms operate. Though there are many different ways to slice up these markets, Netflix is the top streamer by subscriber count. And Warner, through HBO Max, is the third biggest streamer by subscriber count. So consumers would have fewer choices. We already know that there’s market power here, as Netflix and HBO Max have been raising prices substantially. But that’s not all. These two firms are also big buyers of professionally produced content, meaning they’d have increasing leverage over the directors, writers, actors, producers, and film crews who rely on playing one studio against another. Finally, Warner is a major supplier of intellectual property combining with a giant distributor, so it’s also a supplier-customer relationship. Netflix-Warner would have the incentive to stop providing its content to rivals like Amazon, Comcast, or Paramount, and to stop buying content from them. To understand whether this merger violates the Clayton Act, let’s look at the 2023 merger guidelines from the Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission. These were created to modernize merger law, but they are based on court precedent. I don’t want to get into too much detail, but this deal would violate almost every single one of them. It’s a merger in a highly consolidated market that’s already been consolidating, one of the merging firms already has a dominant position that the merger may reinforce, it could cut off the supply of products its rivals use to compete, it fosters buying power against workers, creators, suppliers, or other providers, and so on and so forth. That doesn’t mean a judge will definitely find the deal to be unlawful. There are other ways to define these markets. If you just look at all of TV and video consumed, versus paid subscribers for streaming, then Netflix and Warner each have a small share. YouTube is a potential competitor, so one could argue that consumers and suppliers have other places to go. Moreover, enforcers have to prove market power, and weird stuff happens at trials. Judges can be iconoclastic; some of them really like mergers, and place a very high burden in front of plaintiffs. But I would find “all video everywhere” market definition too broad, and I suspect most judges would as well. Regardless of where antitrust lawyers come down, all of them agree there’s definitely a case against this deal. But the second question is, will anyone actually bring it? And that’s where it gets political. Will This Deal Be Challenged?Let’s start with the Federal government. While the Department of Justice Antitrust Division has traditionally been mostly independent, that’s not the case under this President. It won’t be Antitrust chief Gail Slater making the decision about whether to challenge the deal, it’ll be Trump. And Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos has been personally meeting with him. So far, however, it doesn’t look like the Netflix charm offensive is working. Here’s Trump outside of the Kennedy Center today, asked about whether he will challenge the deal.

That’s not good for Netflix, though this administration has a reputation of being open to purchase. At the same time, Trump already has a good relationship with billionaire Larry Ellison, whose owns rival Paramount, and who is a scorned suitor of Warner. But Trump can’t just stop the deal, his administration has to actually go to court and get an injunction from a judge to do that. And there we get to the competence question. The Antitrust division has been bleeding litigation talent since Trump took office. The reason is simple; it’s demoralizing to work at a place where you’re analyzing a merger or doing litigation not for the public interest, but to see if it’s possible for the President to extract what often looks like a bribe. So even if the DOJ wanted to bring a case, they may lack the ability to do it well. Still, they should be able to cobble something together. A different possible set of challengers are states, each of which has a chief law enforcement officer who can bring a case. A number of states do have the capacity to litigate against this merger on their own or jointly, from California to New York to Tennessee to Colorado to Arizona. And that does happen sometimes; Kroger-Albertsons, for instance, drew a Federal Trade Commission challenge, but was also attacked separately by Colorado and Washington state. Plus, the Democratic leaning states have recently brought on fierce anti-monopolist Rohit Chopra in an advisory role, so that’s a good sign. Still, it’s a big lift for a state to go after an $82 billion merger like this. The question here is whether state enforcers would have the guts to actually dedicate the resources to this particular case. I don’t have an answer to that. A lot of it depends on whether and how much Hollywood chooses to speak out. Industry opposition is real - documentary filmmakers oppose it, since it’s hard to distribute documentaries with fewer channels. The writers are against it, so are producers. Paramount will oppose it, as will the National Association of Theater Owners. So we’re set up for a real battle here, and potentially an amazing trial in which all sorts of secrets will be revealed. And if that happens, well, it gets back to greed. A few years ago, this acquisition would have been greeted with joy; Netflix will get Game of Thrones and the Sopranos and Harry Potter and all for a reasonable monthly price? Wow! But while originally seen as a great service when it launched, Netflix has been raising prices so much that it blew its cultural credibility by being greedy. Americans have had it with the high cost of living, and they are letting their political leaders know it. As a friend of mine said, people aren’t particularly excited to pay more for streaming and see Wall Street destroy the movie industry, all so that some rich guy can go on another space vacation. And now, the rest of the monopoly round-up. It’s not just Hollywood that’s mad at monopolies, cowboys are furious at big meatpackers, so are NASCAR team owners and even Michael Jordan. Plus, Larry Summers is now banned from the American Economics Association, the final judgment in the Google search remedy case is out, and there’s an intriguing new legal theory on prosecuting Mark Zuckerberg for child endangerment. Read on for more... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |