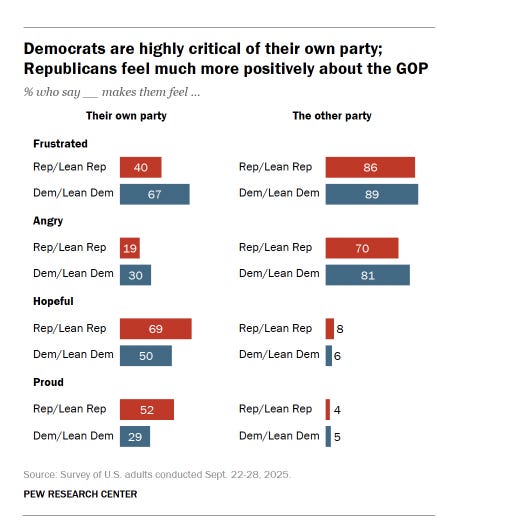

Even In a Populist Moment, Democrats Are Split on the Problem of Corporate PowerDemocratic voters have turned against big business, but only the progressive faction of the party has listened. This distance between voters and leaders is unusual and can't go on forever. Or can it?Americans are extremely angry about corporate power. Polling shows that views about big business are at a 15-year low, and overall perceptions of capitalism are dire. Videos on TikTok about weird corporate scams, dynamic pricing games, and junk fees are pervasive. Law firms that specialize in jury selection are warning big companies that people have a “deep skepticism of corporate America. People increasingly feel that too many aspects of their lives are out of their control and that they are helpless to address the issues confronting them.” 94% of Democrats and 66% of Republicans think the rich have too much influence over politics, and former FTC Chair Lina Khan has become a folk hero online. There’s a reason for this populist rage. The cost of living is high, consumer sentiment is abysmal, and corporate profit margins are at a record. No matter where you look, the extraction is obvious. Netflix prices are up 125% since 2014, the cost of taking your dog to the vet increased by 10% last year, and paying for a child to play in a sport has jumped by 46% since 2019. More Perfect Union just came out with a report showing that big grocery stores are charging different prices for the same product based on surveillance dossiers gathered about you. The political impacts are becoming obvious. A month ago, Zohran Mamdani won the race to be the new mayor of New York City, shocking the political establishment with a campaign focused on high prices and high rents. Local governments are rejecting data centers all over the country. Two days ago, Maine Senate candidate Graham Platner went viral with a tweet attacking the Netflix-Warner merger, saying “these assholes want to kill moves so they can get richer and richer.” Platner has never run for office, and yet he’s leading the former Governor of Maine, Janet Mills, in the Democratic primary. And it’s not just this year, there’s a story of increasing voter rage going back two decades. In 2006, 2008, 2010, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2022, and then last year, voters said “throw the bums out” in change elections. Barack Obama bailed out the banks, and Democrats got wrecked. Joe Biden doubled the number of billionaires on his watch, and voters turned his successor down. Donald Trump has largely hewed to a pro-oligarch position, and the Republicans are being destroyed. I don’t want to be overly pessimistic about the Democrats, so what I’ll note is that there is good news and bad news. The good news is that the progressive faction of the party, after a long period of loose alignment with corporate America on social questions, is breaking with the oligarchs. Take the Netflix-Warner-Paramount bidding war to consolidate Hollywood. When Netflix announced its acquisition, Senator Elizabeth Warren opposed it sharply, arguing that a “Netflix-Warner Bros. deal looks like an anti-monopoly nightmare.” Her Senate colleague Chris Murphy said it’s a “disaster” and “patently illegal,” while Bernie Sanders claimed that it shows “oligarch control is getting even worse.” Cory Booker, Becca Balint, Marc Pocan, Chris DeLuzio, Pramila Jayapal, and others have expressed concerns. In California, Silicon Valley Congressman Ro Khanna and gubernatorial candidate Tom Steyer are opposed. Since the Obama era, progressives had over-indexed on unpopular social questions favorable to corporate America. That era appears to be over. But there’s also bad news. Within the elite of the Democratic Party, among the tens of thousands of elected officials and staffers and operatives and lawyers who comprise the bureaucratic machinery of the party, there’s a deep division about whether corporate power has any relationship to what voters care about. For instance, not a single California politician outside of Steyer and Khanna has opposed the Netflix-Warner merger, which will devastate the entertainment industry in the state. But this dynamic goes far beyond this one particular deal. Take three minor events in the last week. Four days ago, Democratic party bigwig Ezra Klein, who is a key voice shaping the Democratic attack on populism, wrote about antitrust law. But he was actually attacking it, criticizing the use of antitrust law to address Meta’s market power. Then three days ago, it came out that Maryland Governor Wes Moore, a 2028 candidate, made sure to have lobbyists for the American Gas Association in the room when he interviewed for open seats to the state Public Service Commission, even as utility prices spike. And finally on Monday, Democratic House leader Hakeem Jeffries created a “Democratic Commission on AI and the Innovation Economy,” in which he appointed a set of Silicon Valley-friendly Democrats to “develop policy expertise in partnership with the innovation community.” This task force is led by Rep. Valerie Foushee, who released a report over the summer encouraging a weakening of antitrust laws, as well as Ted Lieu, who argued that regulating Google’s ability to suppress or promote content violates the first amendment. It’s notable that Lieu represents Los Angeles, and has not mentioned the consolidation of his major home town industry. But he’s “honored” to be part of this AI task force. Indeed, this announcement looks suspiciously like it could mean trading policy favors around artificial intelligence for campaign donations by big tech oligarchs. This steady drip-drip-drip of corporatism is what Democrats are hearing from their leaders. Indeed, the Democratic agenda for 2026 is being overseen by wealthy corporate-friendly activists. Jeffries is workshopping a Democratic slogan for 2026, “strong floor no ceiling,” which is a phrase he cribbed from a book written by a Democratic donor, venture capitalist Oliver Libby. Libby’s ideas include “more private-public partnerships to rebuild our infrastructure grids,” a Fair Rules Commission to cut red tape, tax credits for preventative health care, and longer patents for drug and biotech companies to help them generate more profits so they can do more innovation. These ideas are no different than you’d find in every Democratic party platform from the 1970s to the 2010s. Moreover, the slogan itself is about supporting the consolidation of wealth and power into a few hands. The term “no ceiling” is about ensuring that America has billionaires. “There is nothing inherently wrong with having a billion dollars. In fact, most people who earned a billion dollars did so by creating something that a lot of people wanted to pay for — I don’t know a more American idea than that,” Libby said. Libby’s appeal to Jeffries is not a surprise; the Democratic leader got his start at the big law firm Paul Weiss. At the Presidential level, this pro-oligarch argument is well-represented. For instance, Kamala Harris recently expressed surprise that billionaires groveled before Trump. “I always believed that if push came to shove,” she said, “those titans of industry would be guardrails for our democracy.” While Harris is increasingly a figure of ridicule, her views are not. California governor Gavin Newsom, who is leading in the polls for 2028, is explicit about protecting great wealth. He’s a big recipient of political money from Netflix and Google. And that’s at the top of the party, but it’s pervasive. On Tuesday, popular crypto-backed Texas Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett announced her candidacy for a Senate seat in Texas, and didn’t mention corporations in her announcement speech. Democrat Katie Sieben, the chair of the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, just allowed Blackrock to buy major electric utility Allete, under the premise Blackrock would keep prices affordable. And even as Amazon was handing a $40 million documentary film contract to Trump’s wife, Illinois Governor JB Pritzker vetoed a safety bill that would have merely required the company tell its warehouse workers any quotas on which they are assessed. It’s a truly bizarre dynamic; Trump is the main opponent of Democrats. Despite a populist campaign, he’s now mocking the idea of “affordability” as a Democratic con, pardoning an endless slew of white collar criminals, and overseeing a catastrophic merger spree to monopolize the economy and assume power over the media. He is the personification of corporate power, and Republican officeholders are panicking about how badly they are going to lose in upcoming elections. But the opposition party is split into two factions, one of which makes a case for a different kind of politics, and one of which seems to ignore everything of substance. For much of the Democratic Party infrastructure, economic power just doesn’t seem to be a relevant part of politics. Here’s Hawaii Senator Brian Schatz, widely considered to be the next Democratic Senate leader after Schumer, musing on what is likely to be the Democratic agenda to address “affordability” if they win Congressional majorities. The first two ideas - eliminating tariffs and paying more subsidies to health insurance companies - are both policies sought by big business. More to the point, Schatz isn’t acknowledging the real drivers of high costs, which are middlemen increasing prices in everything from health care to beef to housing to pharmaceuticals. Corporate power just isn’t there. Much of the Democratic Party leadership is ignoring what voters care about. And that is fostering something I’ve never seen in my career. Democratic activists have often been at odds with party leaders, but actual Democratic voters have always approved of them, and been fearful of more assertive populist types. Obama was beloved, despite his pro-Wall Street posture. Hillary Clinton defeated Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Cuomo dominated New York. Yet today, polling shows that Democratic voters are really frustrated with their own party. Back in March, Axios reported on a Democratic member of Congress crying after a town hall, saying: “They hate us. They hate us.” It’s not hard to see why Democratic voters are finding very little that appeals to them within their media and political ecosystem. Their political leaders are pursuing a Bill Clinton-style of “Third Way” politics, what Barack Obama called “the pragmatic, nonideological attitude of the majority of Americans.” Until relatively recently, such an anti-populist approach made sense. Most Democrats thought a billionaire was someone who made a lot of money by doing something smart, often bringing us cool technology. Bill Gates might be aggressive, but he helped develop the personal computer. And this frame wasn’t some centrist thing, it was consensus. In 2011, for instance, when Apple co-founder Steve Jobs died, the protesters at Occupy Wall Street set up a shrine to the billionaire. This dynamic has changed. Over the last 15 years, Americans have started to believe that most great fortunes are extractive by nature. Tech titans used to make cool stuff, but you can only replace the iPhone with something virtually identical so many times before you lose your innovation brand. And with the rise of surveillance pricing and junk fees, people have come to believe that oligarchs don’t work for their money, they simply extract. I’ve only seen this kind of jarring distance between elected political leaders and voters one other time, during the war in Iraq. And there’s some good news in this anecdote. In 2003, the leading Democrat to win the nomination for President was Senator Joe Lieberman from Connecticut, who was the single most aggressive supporter of George W. Bush’s war aims. Until 2005, most elected leaders thought the invasion of Iraq had popular support, until a series of special elections and primaries showed otherwise. In 2006, Joe Lieberman lost his Senate Democratic primary, and in 2008, voters chose the only candidate who had been opposed to the war before it started, Barack Obama, who withdrew troops from Iraq in 2011. Ultimately, the voters did get what they voted for. Today, there’s that same distance between voters and their leaders on the question of corporate power (as well as an adjacent question, which is support for Israel.) Joe Biden didn’t see the anger of voters. Trump is saying affordability is a fake concern. And the Democrats are split between progressives who are finally centering corporate power, and the rest of the institutional apparatus, which doesn’t even see it. I can think of a few reasons why this dynamic exists. The most obvious is money. Running for office is expensive, and there isn’t much money available to people who oppose corporate power. Still, I don’t think that’s the whole story. Labor unions have money, and a lot of politicians get a lot of capital by running on culture war questions, so there are fundraising channels available. Still, money is certainly a factor. Another possibility is that it takes some time before a changed attitude of the public can be reflected by the party apparatus. In some ways, the views of politicians are like the stars in the sky. You actually aren’t seeing the star itself, but light released by that star millions of years earlier as it finally reaches Earth. Similarly, politicians tend to retain the attitude that first got them elected; Chuck Schumer still imagines America as it was in 1980, when he first became a Congressman. As new elections put up new people, the public eventually finds itself represented. Yet, like money in politics, that’s not a totally satisfying answer. There have been change elections since 2006, but the public is less represented than it was. Another part of the story is that the ideology of liberal institutions has until recently been arrayed against decentralizing economic power. Democrats venerate experts and elites, because they see the use of power by normal elected leaders to be grubby or venal in some way, certainly less legitimate than what corporate actors do. Behind that view is an entire religious system. Modern liberalism comes out of the 1970s consumer and environmental rights movements, and it is based on anti-politics, or the idea that working together through the state to structure the rules of our economy is itself an immoral act. I wrote about this last year, talking about the Democratic Party’s “cult of powerlessness.”

This kind of ideological dispute isn’t explicit, but comes through a perverted form of political rhetoric. For instance, when you question the policy views of political candidates, the response from Democratic operatives is bafflement. What matters, they imagine, is whether someone “can win,” and “issues” only matter insofar as they help or hurt a candidate in securing votes. But asking whether a person can win an election is just asking to predict an unpredictable future outcome. The question of “who can win” has little to do with winning, it’s just subjecting candidate selection to a set of wealthy validators. In this framework, politics is not even about choosing a government. In fact, government is barely relevant. “You campaign in poetry,” said former New York Governor Mario Cuomo, “You govern in prose.” That’s an iconic phrase, frequently quoted by Democrats. Yet just think about what it really means, which is that lying to voters is the point of democracy. For as long as I’ve been paying attention to politics and policy, that’s been the attitude among Democrats. Liberal institutions organize themselves around a “loser consensus.” Political leaders and activists are petrified to go outside of a few slogans, because those slogans represent what the party writ large agrees on. They are actually angry when anyone demands they do so, making claims that there’s an attempt to avoid a “big tent” or engage in forms of inappropriate litmus testing, instead of seeing the demand to do the political work necessary to build a society. That’s why most Democratic political leaders have a really hard time talking about corporate power. Taking a position on say, Netflix-Warner would require actually thinking about something that most of the party hasn’t come to a consensus on. It might prompt disagreement and maybe even someone changing their mind. As Netflix founder Reed Hastings is a big Democratic donor, it might offend people in the party who have relationships with him. In his 2006 autobiography The Audacity of Hope, Barack Obama described liberal culture with two observations. The first was about manners. “Every time I meet a kid who speaks clearly and looks me in the eye, who says ‘yes, sir’ and ‘thank you’ and ‘please’ and ‘excuse me,’ I feel more hopeful about the country,” he wrote. “I don’t think I am alone in this. I can’t legislate good manners. But I can encourage good manners whenever I’m addressing a group of young people.” The second was about what motivates him. “Neither ambition nor single-mindedness fully accounts for the behavior of politicians,” he wrote. What drives them “is fear. Not just fear of losing—although that is bad enough—but fear of total, complete humiliation.” When Obama lost a Congressional primary to Bobby Rush in 2000 by 31 points, he would go places in the community and imagine that “the word ‘loser’ was ‘flashing through people’s minds.’” He had feelings of the sort “that most people haven’t experienced since high school, when the girl you’d been pining over dismissed you with a joke in front of her friends, or you missed a pair of free throws with the big game on the line—the kinds of feelings that most adults wisely organize their lives to avoid.” In other words, the two motivating drivers of leaders in American liberal institutions are respect for manners and fear of embarrassment. What Obama described is not the culture of a society or party based on the idea of political equality, or freedom from arbitrary dealings. It is the culture of aristocracy, of reverence for deep hierarchy, of flattery and fear, of social and cultural and financial coercion. It is, in fact, the same culture that has created the monopoly crisis we are dealing with today. You can see this approach with the “Abundance movement,” a group of billionaire-backed liberal elites who feel strongly that the ideas behind the anti-monopoly movement are wrong. Mostly, the response from Democratic insiders has not been, let’s have a debate, but “can’t we all just get along?!?” They want a consensus because they want to be told what to do, they do not want a debate where they have to use their critical thinking faculties. They want polling data and money, both of which are designed to give them not political wins, but emotional comfort. That is the culture of Jeffries, or Newsom, of academic and media elites like Larry Summers and Ezra Klein, of Wall Street and Silicon Valley donors. But the difference is that increasingly, the voters are less obsessed with manners and more interested in prices. Ultimately, as with the war in Iraq in the mid-2000s, the the 2026 and 2028 elections are going to determine where the Democratic coalition goes. Breaking through to a different way to run a country, even if we’re just restoring the traditional American approach, takes a lot of time. We are trying to convince people they should believe in democracy, and it’s still a live debate. Right now, the people who live and breath the aristocratic Democratic Party culture can’t break from it. It’ll take a different, more populist faction to do that. And that’s what is likely to shape political debates for the next few years. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |