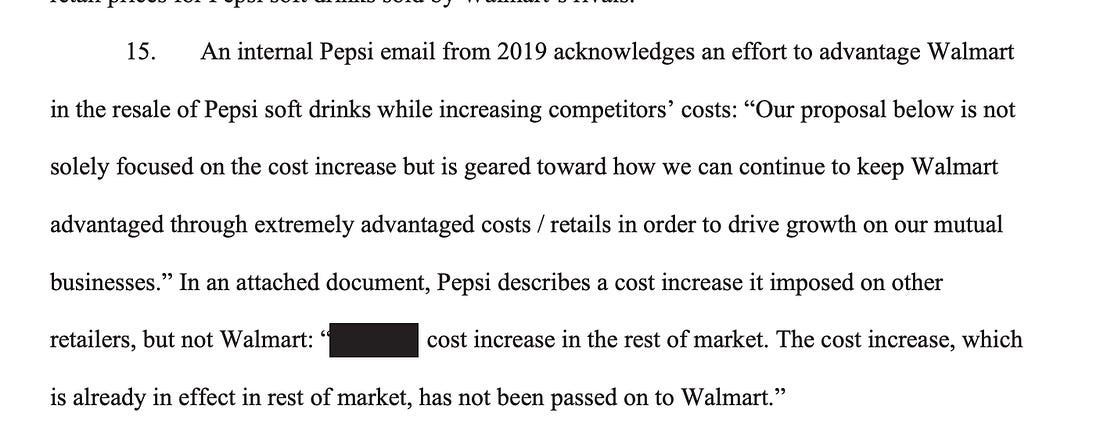

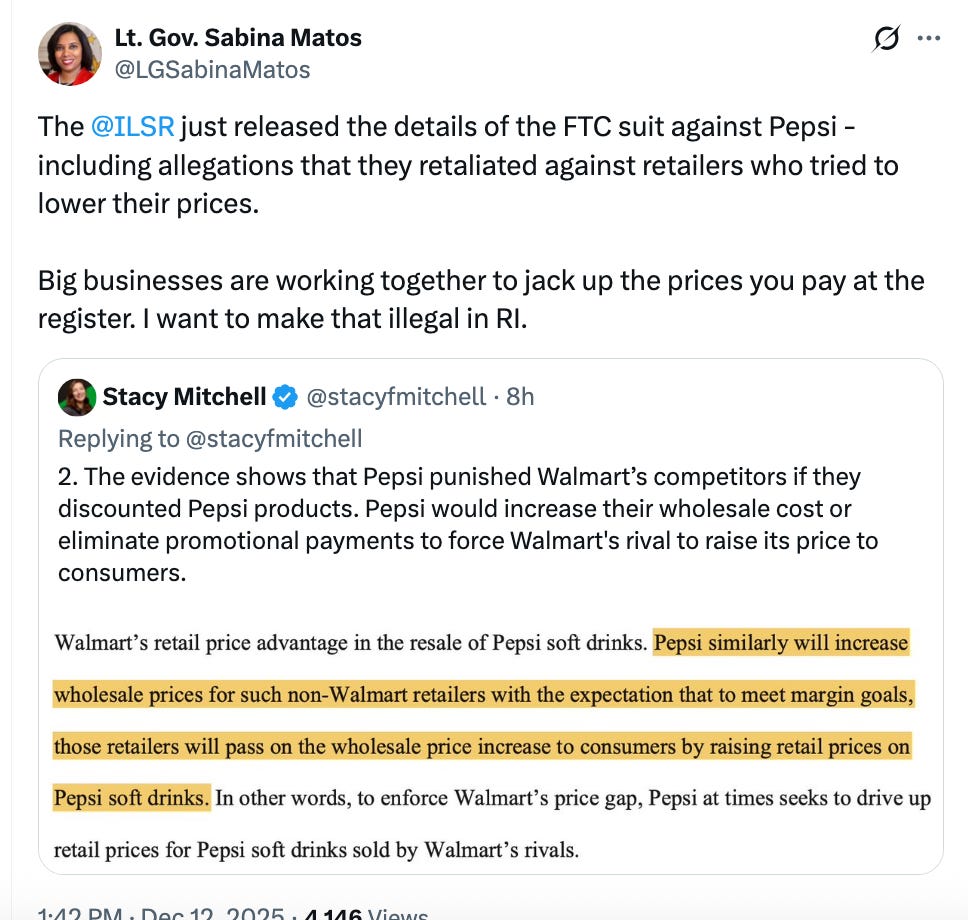

Secret Documents Show Pepsi and Walmart Colluded to Raise Food Prices Across the EconomyThe Trump FTC tried to hide a complaint showing Pepsi forced shoppers to pay higher prices everywhere but Walmart. But now it's unsealed. And the politics of affordability are explosive.Last month, the Atlanta Fed came out with a report showing a clear relationship between consolidation in grocery stores and the rate of food inflation. Unsurprisingly, where monopolies prevail, food inflation is 0.46 percentage points higher than where there is more competition. The study showed that from 2006-2020, the cumulative difference amounted to a 9% hike in food prices, and presumably since 2020, that number has gone much higher. Affordability, in other words, is a market power problem. And yesterday, we got specifics on just how market power in grocery stores works. The reason is because a nonprofit just forced the government to unseal a complaint lodged by Lina Khan’s FTC against Pepsi for colluding with Walmart to raise food prices across the economy. A Trump official tasked with dealing with affordability tried to hide this complaint, and failed. And now there’s a political and legal storm as a result. Let’s dive in. Everyone knows the players involved. Pepsi is a monster in terms of size, a $90 billion soft drink and consumer packaged goods company with multiple iconic beverage and food brands each worth over $1 billion, including Pepsi-Cola, Frito Lay, Mountain Dew, Starbucks (under license), Gatorade, and Aquafina. Walmart is a key partner, with between 20-25% of the grocery market. Pepsi was also a key player in the post-Covid ‘greedflation’ episode. “I actually think we’re capable of taking whatever pricing we need,” said CFO Hugh Johnston in 2022. And the company did just that, raising prices by double digit percentages for seven straight quarters in 2022-2023. The allegation is price discrimination, which is a violation of the Robinson-Patman Act, a law passed in 1936 to prevent big manufacturers and chain stores from acquiring too much market power. The specifics in the complaint are that Pepsi keeps wholesale prices on its products high for every outlet but Walmart, and Walmart in return offers prominent placement in stores for Pepsi products. This approach internally is called a “price gap” strategy. It’s a partnership between two giants to exclude rivals by ensuring that Walmart has an advantage over smaller rivals in terms of what it charges consumers, and so that Pepsi maintains its dominance on store shelves. This partnership comes in a number of forms. Pepsi offers allowances for Walmart, such as “Rollback” pricing, where specially priced soft drinks go into bins in highly visible parts of the store. The soft drink company gives Walmart “Save Even More” deals, online coupons and advertisements, and other merchandizing opportunities. Other outlets don’t get these same allowances, meaning they are charged higher prices. While Pepsi is a “must-have” product for grocery stores, Walmart is also massively powerful. In its investment documents, Pepsi notes that Walmart is its largest customer, the the loss of which “would have a material adverse effect” on its business. Walmart is so dominant that the internal communication of the two companies would show a comparison of prices at Walmart versus “ROM,” or “rest of market,” meaning grocery, mass, club, drug, and dollar channels. It’s everyone in the world versus Walmart. And Pepsi does a lot of alleged price discrimination to maintain the approval of Walmart. It goes far beyond special allowances and concessions to Walmart; Pepsi even polices prices at rival stores and prepares reports for Walmart showing them their pricing advantages on Pepsi products. When the “price gap” would narrow too much, Pepsi executives panicked with fear they might offend Walmart. They tracked “leakage,” meaning when consumers would buy Pepsi products outside of Walmart, which happened most often at stores where prices were more competitive. Pepsi kept logs on stores who would “self-fund” discounts, nicknaming them “offenders” of the price gap. It would note that where competition was fierce, such as in the Richmond-Raleigh-CLT corridor, it was harder to maintain a price gap for Walmart. This relationship went both ways; Walmart executives would complain to Pepsi if the “price gap” got too thin. To ensure that prices would go up at rival stores, Pepsi would adjust allowances, such as “adjusting rollback levers.” It would punish stores that refused to cooperate by raising wholesale prices. Retailers who were trying to discount Pepsi products to better compete with Walmart would find it increasingly difficult to do so; not only would Pepsi take away their promotional allowances, but they might find that discounting six-packs of soda would lead to Pepsi charging them higher wholesale prices for the soda. The FTC offered the example of Food Lion, a 1000-store chain in 10 states that cut prices on Pepsi products on its own to match or beat Walmart prices.

This arrangement benefits each side by extracting from consumers and rivals. Walmart gets to have a price advantage in Pepsi soft drink products against rival grocery stores and convenience stores, and Pepsi is able to exclude competitor access to better shelf space at the most important retailer. Consumers end up paying more for soda, new companies find it harder to get distribution access for new soft drink products to compete with Pepsi, and all non-Walmart retail stores are put at a disadvantage to Walmart. ILSR’s Stacy Mitchell laid out the terms of the deal as “Keep us the king of our domain and we’ll make you the king of yours.” This dynamic is why independent grocery stores are dying. “We can be almost certain that this is the same monopolistic deal Walmart has cut with other major grocery suppliers,” noted Mitchell. “It’s led to less competition, fewer local grocery stores, and higher prices.” To the end consumer, it creates an optimal illusion. Walmart appears to be a low-cost retailer, but that’s because it induces its suppliers to push prices up at rivals. The net effect is less competition at every level. There are more areas without grocery competition, which increases food inflation. And suppliers like Pepsi gain pricing power, such as that they exploited during the post-Covid moment. This kind of presumptively illegal price discrimination isn’t unique to the Pepsi-Walmart relationship. Pepsi is also being sued in a class action complaint for giving better deals for snack foods to big chains than it does to smaller stores, and Post is being sued by Snoop Dogg for working with Walmart to exclude sugar cereals produced by Snoop Dogg from its store shelves. You can find price discrimination everywhere in the economy, from shipping to ad buying to pharmaceutical distribution to liquor sales. And the resulting consolidation and high prices is also pervasive. So why are we only learning about this situation now? Well, the original allegation was filed in January, in the last days of the Khan FTC. We knew the general outline of the argument, but we didn’t know specifics, because the complaint was highly redacted. Was it a real conspiracy? Was it just that Pepsi considered Walmart a “superstore” and had different prices for different channels? Was there coercion? None of these questions could be answered; there were so many blacked out words we couldn’t even say for sure that the large power buyer referenced in the document was Walmart. Economists and fancy legal thinkers mocked the case endlessly. The FTC hates discounts! Price discrimination is good, it ends up lowering prices for consumers. The Robinson-Patman Act is stupid and pushes up prices. Suppliers always can only charge what “the market will bear” and if they could charge higher prices they’d already be doing it. And they’d never offer lower prices to any distributor; no lower than they had to. Yet these claims relied on the complaint never seeing the light of day. The reason for the secrecy was a choice by FTC Chair Ferguson. Normally, when the government files an antitrust case, the complaint is redacted to protect confidential business information, as this one against Pepsi was. Then the corporate defendant and the government haggle over what is genuinely confidential business information. Within a few weeks, complaints are unsealed with a few minor blacked out phrases, and the case goes on. In this case, however, Trump Federal Trade Commission Chair Andrew Ferguson abruptly dropped the case in February after Pepsi hired well-connected lobbyists. Small business groups were angry, but what was most interesting was the timing. Ferguson ended it the day before the government was supposed to go before the judge to manage the unsealing process. And that kept the complaint redacted. With the complaint kept secret, Ferguson, and his colleague Mark Meador, then publicly went on the attack. Ferguson’s statement was a bitter and personal invective against Khan; he implied she was lawless and partisan, that there was “no evidence” to support key contentions, and that he had to “clean up the Biden-Harris FTC’s mess,” which fellow commissioner Mark Meador later echoed. And that was where it was supposed to stay, secret, with mean-spirited name-calling and invective camouflaging the real secret Ferguson was trying to conceal. That secret is something we all know, but this complaint helped prove - the center of the affordability crisis in food is market power. If that got out, then Ferguson would have to litigate this case or risk deep embarrassment. So the strategy was to handwave about that mean Lina Khan to lobbyists, while keeping the evidence secret. However, the anti-monopoly movement and the court system actually worked. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance, an anti-monopoly group filed to make the full complaint public. Judge Jesse Matthew Furman agreed to hear ILSR’s case, with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Pepsi bitterly opposed. Last week, Furman directed the FTC unseal the complaint. So we finally got to see what Ferguson and Meador were trying to hide. The political reaction is just starting. Ferguson has pretended that he’s taking a leading role in the ‘affordability’ strategy of the Trump administration, it wouldn’t surprise me if there’s internal anger at him among Republicans for flubbing such an obvious way to lower consumer prices and then lying about it. The grocery industry, especially rural grocers victimized by this price discrimination, leans to the right. On the Democratic side, already we’re seeing states introducing price discrimination bills. There’s likely going to be bipartisan pressure on the FTC, which can and should reopen the case. There are already private Robinson-Patman Act cases, this complaint is likely to be picked up and used by plaintiffs who are excluded by the alleged scheme revealed in it. As a result of the publication of this complaint, Sabina Matos, the lieutenant governor of Rhode Island, just said that her state should ban this kind of behavior. But there’s also something deeper happening. Earlier this week, More Perfect Union came out with an important investigative report on a company called Instacart, which is helping retailers charge individual personalized prices for goods based on a shopper’s data profile. The story went viral and caused immense outrage because it said something we already know. Pricing is increasingly unfair and unequal, a mechanism to extract instead of a means of sending information signals to the public and producers to coordinate legitimate commercial activity. And there’s a historical analogy to the increasing popular frustration. The idea of the single price store, where a price is transparent and is the same for everyone, was created by department store magnate John Wanamaker in the post-Civil War era. Before founding his department store, Wanamaker was the first leader of the YMCA. He also created a Philadelphia mega-church. His single price strategy was part of an evangelical movement to morally purify America, the “Golden rule” applied to business. The price tag was political, an explicitly democratic attempt to treat everyone equally by eliminating the haggling and extractive approach of merchants. At the same time as Wanamaker operated his store, the Granger movement of farmers in the midwest and later Populists fought their own war on unfair pricing of railroads, with the slogan “public prices and no secret kickbacks.” In the 1899 conference on trusts in Chicago, widely considered the most important intellectual and political forum for the later treatment of the Sherman Act, there were bitter debates, but everyone agreed that price discrimination by railroads were fostering consolidation in a dangerous and inefficient roll-up of power. These movements took place at a moment of great technological change, when Americans were moving to cities and leaving the traditional dry goods store behind. Similarly, there was a big anti-chain store movement in the 1920s and 1930s to protect local producers and retailers, which ended up resulting in the Robinson-Patman Act, among other changes to law. That was a result of the Walmart or Amazon of its day, A&P, which would engage in price discrimination, opening outlets it called “killing stores” just to harm rivals. Over the past five years, we’ve seen a similar upsurge in anger over prices that drove the grangers, John Wanamaker, and the anti-chain store movement. Prices are becoming political again. This revival is being driven by two things. First, technology is enabling all sorts of new ways to price, which is to say, to organize commercial and political power. And we all feel the coercion. Second, we’re beginning to relearn our traditions. Our historical memory was erased in the 1970s by economists, who argued that price discrimination is affirmatively a good thing. But fortunately, they are losing the debate. As a result, today we’re seeing something similar to the anti-chain store movement of the 1920s and 1930s, with attempts to reinvigorate Robinson-Patman, and write and apply antitrust laws to algorithmic pricing choices. The Instacart scheme is a new way to extract, the alleged Walmart-Pepsi scheme is a classic way to extract. But increasingly, the public is realizing that pricing is political. And they don’t want to be cheated anymore. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller. This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |