How Wall Street Ruined the Roomba and Then Blamed Lina KhanThis week's bankruptcy of iRobot, the maker of the Roomba vacuum, is about more than a robot cleaner. It's about monopolies, Wall Street, and economists leading America on a path of destruction.A few days ago, consumer products company iRobot, the maker of iconic Roomba automated vacuum cleaner, declared bankruptcy. The CEO, a branding and mergers expert named Gary Cohen, sadly announced that the firm could not continue as a going concern. The board, full of lawyers and financiers but not robotics experts, voted to sell iRobot off to Shenzhen Picea Robotics, the Chinese company to which it had offshored manufacturing. There are about 20 million active Roomba vacuum cleaners in operation, and unless Trump regulators or antitrust enforcers act, now all the data harvested from our homes will go to China. The co-founder of iRobot, Colin Angle, was not introspective about this collapse, nor did he associate it within the broader context of the many firms who have had their technology transferred to China. Instead, he, like much of Wall Street, blamed the bankruptcy on Lina Khan. Why? Well she ran the Federal Trade Commission when it investigated Amazon’s possible acquisition of the company in 2022, a deal the two companies ultimately called off. Here’s Angle:

Many Wall Street dealmakers and foes of antitrust enforcement echoed this sentiment. For instance, former Obama chief economist Jason Furman, who is now the Aetna Professor of the Practice of Economic Policy at Harvard, used it as an example of the problem with populist economics. Blocking mergers, he believes, leads to destructive outcomes and national security problems. So is Furman right? This critique matters, because the goal here is to return to the economic statecraft of Bush and Obama, a time when the consensus was that concentrating capital would generate positive outcomes, while restraints on capital would hinder growth. The modest burst of populism around antitrust under Joe Biden deeply shook Furman. With iRobot’s bankruptcy, there is now an opportunity to make the claim that any attempt to restrain Wall Street is a mistake. So what exactly happened with iRobot? And what kinds of lessons should we draw? “What is it about capitalism you don’t understand?”I first came upon iRobot years before the Amazon merger, when I edited a piece by defense analyst Lucas Kunce on Wall Street and national security. I had gotten interested in the collapse of the defense base, a crisis which is now widely discussed, but at the time wasn’t well-understood. Part of that collapse was a result of a phenomenon where financiers would force technology companies to stop innovating. iRobot fit perfectly in that story. I watched a 2017 hearing in the House Armed Services Committee where a former Vice Admiral for the Navy, Joe Dyer, testified. After leaving the Navy, Dyer worked in operations at the robotics firm, when the company was far more than a consumer firm focused on importing automated cleaning tools from China. Here’s Kunce:

In the mid-2010s, during Furman’s tenure running economic policy under Obama, the company sold its defense business, offshored production, and slashed research, a result of pressure from financiers on Wall Street.

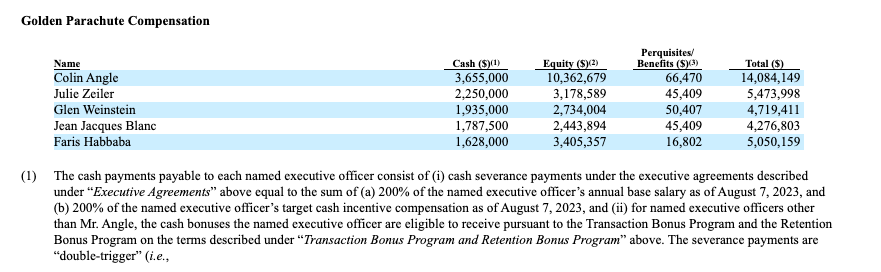

This is a sad story, it’s also a common one. China has captured technology and key process leadership from American and European firms, across everything from rare earths to batteries to chemicals to robotics. And the driver is that the American model of running corporations is to focus on “asset light” cream-skimming, which is to say, focusing on lines of business where the return on capital is exceptionally high. Conversely, the Chinese government, to preserve and extend its particular authoritarian model, actually suppresses the return on capital for its financiers, forcing an “asset heavy” approach. They overly emphasize factories and engineering. The net effect of these two complementary forces used to be celebrated as “Chimerica,” where China produces and the U.S. consumes. The consequence of this dynamic is the movement of production from America to China; iRobot is just one example out of many. But there’s another dynamic aside from trade, and that has to do with a peril of market power. Like a lot of firms with seeming dominance, such as Boeing and Intel, iRobot had a big market share, but its operational capacity degraded quickly as financiers forced the company to harvest its monopoly and add nothing back. Under a trade regime overseen by men like Furman, the company offshored production, thus teaching its future rivals in China how to make robot cleaners. Amazon SidewalkAt any rate, by 2022, iRobot still had a dominant share of robot vacuum cleaners, but competition had become meaningful. Enter Amazon. In the late 2010s and early 2020s, big tech firms were seeking to dominate the “smart home” market, as well as building out networks around the “internet of things” and cloud computing. Amazon was engaged in a roll-up of the smart home space. It had built out the Alexa audio device, and bought the Ring security/doorbell firm (which had acquired smart lighting firm Mr. Beams), as well as the wifi firm Eero in 2019, and video camera firm Blink. It was a very expensive strategy; Ring was nearly bankrupt when Amazon overpaid for the company. According to the Wall Street Journal, between 2017 and 2021, Amazon lost more than $25 billion in losses from its devices business.” But Amazon continued. In 2022, it announced the acquisition of iRobot for $1.7 billion. This deal would seemingly solve iRobot’s problems stemming from a lack of research and production capacity. It would also make people very wealthy. Angle himself would receive $14 million upon completion of the deal, and the entire executive team would be paid lavishly. Nevertheless, Amazon is a very powerful firm, so the FTC, as well as European enforcers, began an investigation. In late 2023, the Europeans issued a preliminary statement of objections, which isn’t a formal challenge but a note to Amazon suggesting there might be problems. The EU argued that Amazon might self-preference its robot vacuum cleaners on its ubiquitous marketplace, and thwart competition. The FTC didn’t bring a challenge, but nevertheless, in 2024, Amazon and iRobot called off the deal. The FTC issued a vague statement announcing it was pleased with the end of the transaction. “The Commission’s probe focused on Amazon’s ability and incentive to favor its own products and disfavor rivals’,” it wrote, “and associated effects on innovation, entry barriers, and consumer privacy. The Commission’s investigation revealed significant concerns about the transaction’s potential competitive effects.” I don’t know what the FTC found, that’s confidential. But I spoke with a former employee of Ring and Latch who explained Amazon’s monopolization strategy. This person’s view is that Amazon wasn’t trying to dominate the robot vacuum cleaner market for its own sake, but as part of a much bigger plan. With Ring, Eero, Alexa, and iRobot devices, Amazon would have the largest network of consumer internet of things (IoT) devices in the world. Here’s what this person argued about this set of acquisitions:

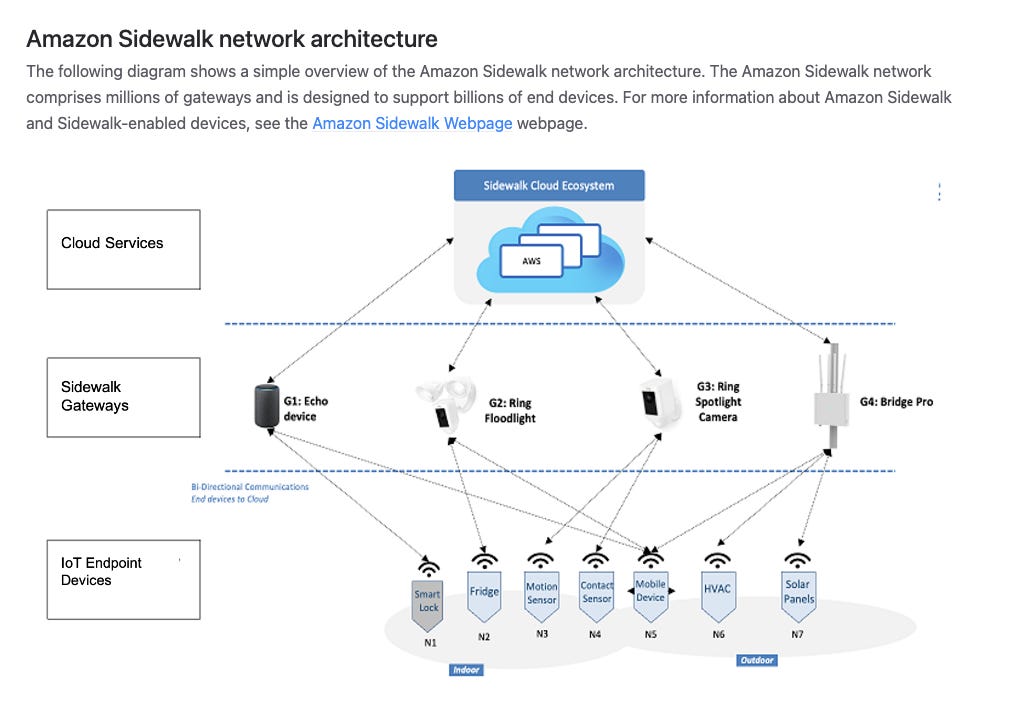

As these devices can connect with each other, they would become the “basis of a physical network connecting devices and sensors all over the world.” This argument isn’t speculation; my source was the first Ringnet/sidewalk product manager at Ring, directly responsible for integrating Iotera technology into Ring camera, Mr. Beams, and Ring Alarm. This person wrote strategy docs, organized legal/business requirements, and coordinated hardware and software development across all the different units. There’s also a lot of public evidence. Here’s Amazon describing this network:

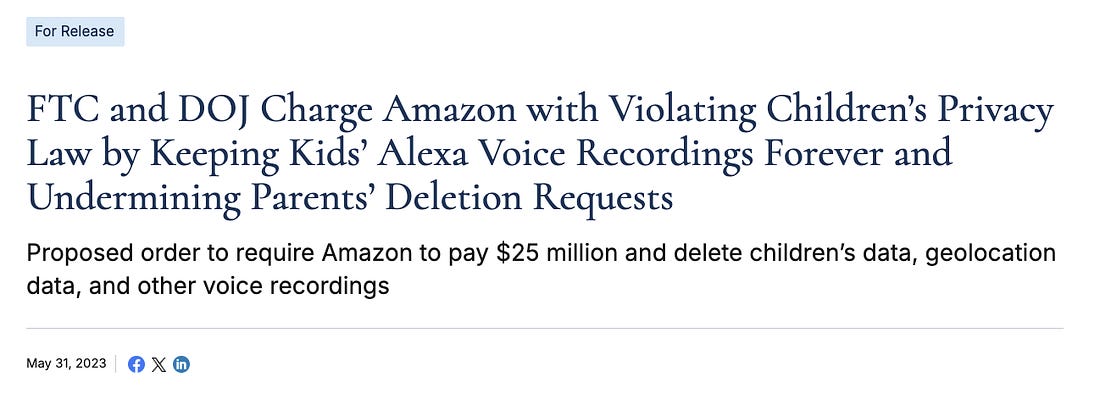

Amazon even renamed its satellite service, Project Kuiper, to Leo, pivoting away from consumer access a la Starlink to fostering this IoT backbone. Sidewalk would let consumers stay connected, without broadband, through a proprietary surveillance heavy Amazon-run network. This situation probably set off alarm bells among enforcers. Amazon has a vast surveillance apparatus, and its devices business had already been charged multiple times by the government with violating privacy laws. At one point, Ring was accused of “allowing any employee or contractor to access consumers’ private videos and by failing to implement basic privacy and security protections, enabling hackers to take control of consumers’ accounts, cameras, and videos.” One government complaint alleged that a Ring employee “viewed thousands of video recordings belonging to female users of Ring cameras that surveilled intimate spaces in their homes such as their bathrooms or bedrooms.” And it wasn’t just the FTC, there was substantial concern from rivals and consumer advocates over Amazon’s use of Sidewalk to open up a new path to surveil consumers. It wasn’t just a consumer strategy. Amazon is now selling access to Sidewalk to industrial customers, linking access to Sidewalk to its cloud computing service Amazon Web Services. In other words, Amazon was seeking to become the proprietary backbone for any industrial firm who wants to link a device with 90% of America, outside of cellular networks, and that could include maps of most homes and neighborhoods. Amazon spent $25 billion on its device network, and would have been perfectly happy to engage in self-preferencing and predatory pricing of iRobot products to further its aims. After this acquisition, Amazon would add iRobot’s suite of products and IP to its own portfolio, as well as the rich network and stream of data. But such a merger likely wouldn’t have helped prevent national security problems or kept robotics capacity in the U.S. Amazon is known to be aggressive about ensuring that production happens in China, so it’s almost a certainty manufacturing would continue there, and Chinese firms would likely still come to dominate most non-U.S. and European markets. For Amazon, the goal was the network, not to make robots. When the deal fell apart, Amazon paid iRobot a $94 million break-up fee, which could be significantly more than the cost of litigating a case, so it is clear the two firms thought the FTC could have challenged it and might have won. After the failed merger, Angle stepped down as CEO, but expressed optimism, saying that “iRobot now turns toward the future with a focus and commitment to continue building thoughtful robots and intelligent home innovations that make life better, and that our customers around the world love.” Antitrust AmnestyIn 2024, when the two firms decided not to move forward with the deal, iRobot hired a “turnaround” specialist named Gary Cohen to run iRobot. The Carlyle Group had lent $200 million to iRobot to help the company get through the merger, and when that merger fell apart, it ended up taking nearly 80% of the breakup fee. Could iRobot have continued as a viable firm? Well Angle publicly said it could, and iRobot executives almost certainly framed it that way to the FTC. Had iRobot truly been insolvent, they could have used a legal argument known as a “failing firm” defense, meaning explaining to regulators they would have gone out of business without a merger. But that would have likely caused Amazon to reduce the price it would have paid to shareholders, including, presumably, the golden parachutes going to the executive team of iRobot. By 2025, the board likely concluded that iRobot could never get the high returns on capital that its board of financiers expected. The losing battle with Red Mountain Capital in 2016 had taught Angle not to build robots and innovative products, but to asset strip. When his company actually had to once again build, they threw in the towel. Carlyle sold the remaining debt at a loss to Shenzhen, which then seized the remaining branding and intellectual property. There’s an interesting question about whether Shenzhen should be allowed to acquire iRobot, but which involves not only antitrust, but foreign acquisitions and national security. There is a government body that makes such decisions. It’s called the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., or CFIUS. And CFIUS, which presumably allowed this acquistion, is led by… Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. In other words, the story here is Wall Street destroying a promising robotics enterprise through financial engineering, aiding the Chinese in the process, and then demanding a bailout via amnesty from antitrust laws so that shareholders wouldn’t lose any money, while refusing to acknowledge that a key Trump ally of Wall Street facilitated the transfer of the firm to China. Of course, this bad faith is routine. None of the critics of antitrust enforcement, including Furman, care if U.S. technology flows to China or if companies fail. They in fact celebrated offshoring when it happened to 90,000 manufacturing plants from 2000 onward, and they often make the point that failure is part of capitalism. But when it comes to one specific company, where they can cherry pick information to make a case against antitrust, well then, all of a sudden iRobot’s bankruptcy is a disaster. All that said, there is an important lesson here for anti-monopolists. Antitrust is a useful tool, but it cannot substitute for a broader national economic development strategy. Right now, America, through a whole set of policy choices, from bailouts to government contracts to pro-speculation regulations to attacks on the rights of labor and creators, ensures that financiers get an unfairly high return on capital. We can see the consequences in everything from the collapse of iRobot to the destruction of America’s cattle herd to the erosion of capacity in Hollywood to the financialized AI data center build-out. The business of America right now is extraction, not creation. To reverse this strategy, a more assertive antitrust regime is necessary, but it’s not enough. We also have to reduce the many other public levers of support for elevated returns on capital. Only then will it make sense for companies like iRobot to invest in robots instead of share buybacks. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |