|

In this issue: - Delivery Platforms and Synthetic Social Trust—Everything I learned from telling millions of people about getting temporarily scammed out of a poke bowl.

- Beta—Interactive Brokers' customers are beating the market. That's not necessarily a good thing for their business.

- Material Nonpublic Information—A market can only reflect information from informed traders if there are also plenty of uninformed ones to trade with.

- App Stores—OpenAI's incentive to ship half-baked integrations.

- Gunboat Diplomacy—Not so much "war for oil" as "war for oil supply elasticity."

- Liquid Content—Your TV will remix your movies.

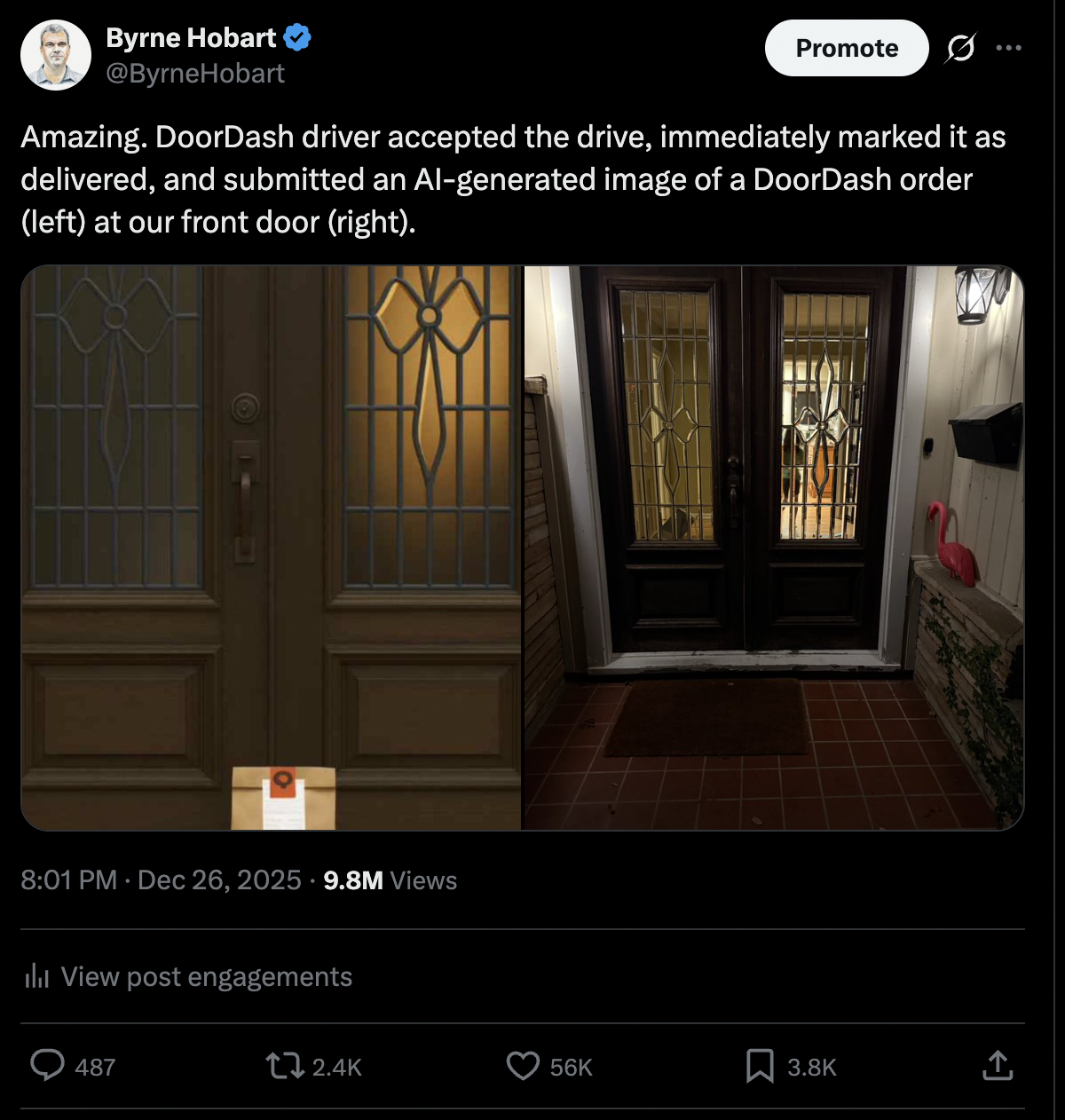

The other night I was feeling lazy and decided to DoorDash dinner, and got a message indicating a successful delivery suspiciously fast—specifically, I got a dropoff confirmation ten minutes after ordering from a restaurant that's a 17-minute drive from my house. Here's a side-by-side of the delivery confirmation photo I got and the actual front door of the house:

A few things to note upfront:

- Not only did DoorDash immediately accept my complaint and dispatch another driver, but the second driver actually arrived within the original order window! "Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds," indeed.

- While this was definitely an attempt to rip me off, I personally came out ahead: in addition to getting the food I ordered on time, this whole situation was incredibly entertaining, and even if I'd had to eat the cost and eat leftovers, the Twitter revenue share from a tweet with 9m views and hundreds of comments is probably more than enough to pay for a private taxi to deliver my next poke bowl. (Also, the next day the DoorDash fraud team called to apologize again and sent me a $50 gift card. So, disclosure, I'm an unsecured DoorDash creditor with a very low cost basis for my investment.)

- DoorDash has a mix of countermeasures that make this hard to pull off—hard enough that plenty of DoorDash drivers who found that tweet were skeptical that it would have happened at all.

Images are easy to fake, as are stories like this one; if you see a tweet like this, you should probably put some probability less than 100% on me telling the truth (in this case I am, and someone else in Austin claimed that the same thing happened, and said the driver had the same name as mine, but he could have been in on it. Anyway, a few days later DoorDash confirmed that it happened. You should also remain cautious here because someone inevitably will do a fake version of this—DoorDash driver forums warn that customers will use AI to alter images of deliveries in order to get a refund).

The default interaction for the driver version of the app lets you make a delivery and then opens up a camera, and you have to take a photo directly in the app, though there's an option to upload one from your photo gallery. (Anecdotally based on the responses to the original tweet, this option isn't displayed consistently, and some drivers aren't aware of it.) And the app also requires the driver to be present at the restaurant when they mark a meal as picked up, and present at the destination when they mark it as delivered.

But, we can put that another way. DoorDash the company is setting these policies while interacting with drivers, but DoorDash the computer program is just interacting with smartphones, or devices that claim to be smartphones. Those devices can be rooted, and configured to report arbitrary GPS coordinates, or to take a photo from some other source and send it to the same API endpoint that the confirmation photo goes to. At first, I assumed that the dasher had just used Google Street View to grab a photo, but the door is actually far back enough from the street that they wouldn't have had a good shot. But, as it turns out the Dasher app actually shows drivers previous examples of other drivers' successful deliveries so they know where to drop things off. So a scammer had an exact reference for the photo they were going to make.

So what probably happened is that the scammer wasn't located anywhere near Austin, and had either breached someone's account or, more likely, bought a list of DoorDash credentials and was systematically running the same scam on all of them (one minor piece of evidence for this is that the follow-up delivery happened so fast—that's more plausible if the meal was already waiting for them). These may have been dormant accounts, because DoorDash requires a one-week waiting period after connecting a new debit card for instant payouts. These might also be new accounts set up specifically to run the scheme. Regardless, there's very little chance that this was done by an active driver who has gone through the trouble of jailbreaking a device and setting up both payments and a little MLOps workflow entirely so they can score the occasional free dinner until they get kicked off the platform.

And this scheme has competition! Using a DoorDash account this way means burning it. If the account was set up by a real person who used a weak password, they'll probably be able to recover it once DoorDash has finished investigating. But it probably doesn't take many repetitions for DoorDash to conclude that either the person isn't getting hacked, but is a bad actor, or that they're so pathologically irresponsible with their username and password that they aren't worth doing business with. Whereas, if you have a DoorDash account and are willing to use it to make money illegally, unless your discount rate is very high indeed your best bet is to rent it to felons, illegal immigrants, previously-banned dashers, etc. There's a whole ecosystem here, and the person who rents out their ID to someone who recruits drivers for them is participating in the easy, passive-income side of it. That sort of blue collar-flavored white collar crime pays a stream of fees for as long as the drivers keep working and as long as customers don't complain that the driver was listed with a woman's name but turned out to be a man. Running that scheme basically requires a Shadow General Manager who recruits illicit drivers and licit IDs. Getting access to one more account in their city is helpful for this person, but if someone gets access to a random account, then a) they won't necessarily be able to find the right contact in that city, and b) they'd have to find some way to have a trusted intermediary, which is a concern on the other side, too—both participants in this transaction know they're dealing with a professional scammer.

You could imagine a few countermeasures here, but they all come with tradeoffs. For example: I don't have the timestamps for everything, but the delivery was reported faster than it could have happened if the driver had instantly picked up an already-prepared meal and driven to my house. DoorDash could perform some sanity-checks here, like getting GPS coordinates every minute to see if the driver is actually transporting the food. That's more work for the scammer—but it actually makes the problem worse, because now there's a longer delay between when the scam happens and when the customer notices. Better to keep fake teleportation as an option because it's a good honeypot.

And one of the big tradeoffs is that there's a cost to imposing friction for either drivers or customers, and the cost of that friction can be a lot higher than the savings from lower fraud. That's especially true in a business that assumes that customers will spend more over time, especially if one of the drivers of that growth is that accumulating purchase data makes it easier to increase order frequency and size by judiciously juggling special offers. If the app gave customers a confirmation number that the driver had to enter in order to confirm a delivery, that would reduce the risk of fake deliveries, or of sloppy dropoffs, but would also erode the convenience of getting something delivered to your door, and would add an unpredictable amount of time to the trip—sometimes a couple seconds, if the customer met the driver at the door; sometimes a little longer if they take a while to get there; sometimes a very long delay if there's a big language barrier or if one of the driver and customer get frustrated. It could easily be the case that they'd make the average order 5% slower in exchange for averting the 1% frequency of scams or misplaced deliveries.

Similarly, they could be more aggressive about ensuring that drivers are who they say they are. They've tightened this up recently, but this is another case where they're imposing friction, which carries a cost. And, had they gotten too aggressive about countermeasures before stories about shared and rented DoorDash accounts got popular, the story could have been about surveillance capitalism and big tech companies assembling a comprehensive database of people's faces for no doubt ominous reasons. DoorDash also has to consider the competition; they're a metonym for the entire industry and are on their way to being a generic verb for app-based delivery. So they have the classic superlinear risk scaling problem: because of their sheer size, edge cases and bad customer interactions will be more likely to happen on their platform than competitors' even if everyone operates in exactly the same way, and it's more newsworthy when it can be associated with a bigger brand name. This is one of the diseconomies of scale in consumer-facing platforms: they have to be stricter than their competitors, but the gravitational force of lower costs from being able to recruit from a wider range of less cost-sensitive drivers—e.g. people who aren't legally authorized to work in the US at all—makes it economically challenging for them to be fully compliant.

The great thing about these platforms is that, from the user perspective, they smooth out the vast majority of the friction you'd naturally experience if you were ordering food prepared by one group of total strangers and delivered by another. The user gets their food promptly, and if for whatever reason they don't, the platform makes them whole. So the experience is that they're unbundling facets of living in a very high-trust society that also has tons of convenient good food—you basically opt in to the experience of living in Tokyo or something (albeit with a price level gap more appropriate for late-1980s Tokyo).

Another way to look at it is that it's analogous to structured products in credit; you really can synthesize a AAA-rated asset backed entirely by lower-rated assets, as long as there's some other slice that can absorb the loss. And, as some people in structured products land discovered to their surprise and displeasure circa 2007-8, the most important but hard-to-model factor is how correlated defaults are. A product with a mix of different kinds of loans to different borrowers in different places can have a bigger AAA-rated tranche than one that consists exclusively of loans to oil companies and airlines. Scalable hacks like this are one of the correlated risks that platforms face; if there's a new vulnerability, it gets exploited at scale and the company faces a string of losses until they find a good way to detect it.

But they do, and at least in this case the first-loss tranche of the social trust structured product pays solid returns for that risk. As with finance, when investors find that their risk in some category is more than adequately rewarded, they tend to invest more in it, and accept lower returns. In DoorDash's case, they didn't initiate that process, but accelerated it—one of the early online delivery services was Seamless, and the name referred specifically to how easy it was to report your dinner spending in order to expense it. White-collar workers have been getting dinner delivered to the office for a long time, but the scale of the modern business means that what used to be a yuppie luxury is now accessible from the front office to the warehouse. It's hardly the most important contributor to the world's material prosperity that a service once consumed by biglaw and ibanking associates is now accessible to Walmart associates, too, but people appreciate the convenience.

And the other side of this is that the dashers benefit from the availability of a Universal Basic Job. It's very much a job rather than a career, but this is part of the implicit social safety net: if you're economically precarious and you get laid off, it's incredibly useful to be able to do little piecework jobs; if you're living paycheck-to-paycheck, being able to convert spare time into a little extra cash is a good way to build a financial buffer or pay off a surprise bill. This is close to the older structure of some labor markets; the way longshoreman jobs once worked was that everyone who wanted to work that morning would show up, and bosses would choose who would be hired for the day and send the rest home. Farming jobs have also worked that way in the past; if it's time to plant or time to harvest, there's a temporary spike in labor demand that's going to go away soon. These systems work best in categories where the demand for work is lumpy and where workers are some combination of unskilled and easy to supervise. That makes them the kind of job you'd hope to only do temporarily while you look for something better. It's a lot better to have access to a boring job you can't wait to quit than to wish you had the opportunity.

So the drivers, too, are opting in to a different kind of trust system. It's incredibly easy for DoorDash to kick a driver off the system for whatever reason, and they already need to be continuously recruiting them because of the job's structurally high turnover. So they can afford to bring lots of drivers onto the system, comp a few customers who interact with the bad ones, and then try to keep the good drivers around as long as possible despite the constant threat of the best of those workers switching to something more stable.

This trust asset is incredibly valuable, but it's really just another way to restate the core of any marketplace business: making it easy for customers to feel like they won't get ripped off, which expands the scope of who they're willing to transact with.

|

You're on the free list for The Diff! We're back from break, so not a lot of paid issues since last time, but upcoming coverage will include a way to rethink the credit-drive AI buildout, diversification through concentration, an S-1 teardown for Motive Technologies, and more. Upgrade today for full access!

|

|

|

|

Diff JobsCompanies in the Diff network are actively looking for talent. See a sampling of current open roles below: - YC-backed startup modernizing the chemicals supply chain—currently a manual tangle of spreadsheets and legacy ERPs covering 20M+ discrete chemicals—is hiring Full-Stack Engineers (React, TS). They’ve successfully deployed their AI-driven pricing and quoting engine to midmarket and F100 enterprises, proving the demand for automated sales enablement in the real economy. Looking for SF-based builders with startup DNA who want to solve hard problems for critical US infrastructure. (SF)

- A PE firm with an exceptional long-term track record of transforming software businesses is looking for ex-consultants/operations executives with experience in procurement and vendor management. (Remote, US).

- A hyper-growth startup that’s turning the fastest growing unicorns’ sales and marketing data into revenue (driven $XXXM incremental customer revenue the last year alone) is looking for a senior/staff-level software engineer with a track record of building large, performant distributed systems and owning customer delivery at high velocity. Experience with AI agents, orchestration frameworks, and contributing to open source AI a plus. (NYC)

- A first-of-its-kind PE firm applying blockchain technology to transform legacy businesses is seeking an Investment Partner to lead deal execution and portfolio management. Ideal candidates have 12+ years of transaction and portfolio experience at leading tech-focused buyout funds (Silver Lake, Vista, Thoma Bravo, Francisco Partners, TA Associates, HG, Thrive Capital, or similar). No crypto experience required—they're looking for elite PE operators who are curious about frontier technology. (NYC)

- A leading AI transformation & PE investment firm (think private equity meets Palantir) that’s been focused on investing in and transforming businesses with AI long before ChatGPT (100+ successful portfolio company AI transformations since 2019) is hiring Associates, VPs, and Principals to lead AI transformations at portfolio companies starting from investment underwriting through AI deployment. If you’re a generalist with deal/client-facing experience in top-tier consulting, product management, PE, IB, etc. and a technical degree (e.g., CS/EE/Engineering/Math) or comparable experience this is for you. (Remote)

Even if you don't see an exact match for your skills and interests right now, we're happy to talk early so we can let you know if a good opportunity comes up. If you’re at a company that's looking for talent, we should talk! Diff Jobs works with companies across fintech, hard tech, consumer software, enterprise software, and other areas—any company where finding unusually effective people is a top priority. Elsewhere

Beta

Interactive Brokers says its customers have outperformed the S&P 500 this year, with its hedge fund clients outperforming by a bigger margin. Interactive Brokers' customers are more sophisticated than those of other mostly-retail brokerages, at least as measured by how much price improvement market-makers offer Interactive Brokers customers compared to other customers. (That particular kind of sophistication would include things like using a series of limit orders to make a trade rather than always buying and selling at market, but it probably correlates with other kinds of financially-responsible behavior.)

Since one of the big attractions of their platform is cheap margin lending, it's easy for the company's customers to run with higher beta than they would at other brokers. And all of that means that, while it's a fantastic company with great financials, it's also incredibly levered to the market; the S&P's maximum drawdown during the financial crisis was 57%, and IBKR's revenue dropped by 44% in the quarter that drawdown finally ended. It takes a lot more than that to kill a company with their margins, but a lot less than that to rerate.

A trader joined Polymarket, bet $30k on markets related to Maduro losing power, and made $437k in profit in a few hours. The Diff has discussed this before—not just the concept of using prediction markets to bet on political events but the specific hypothetical of insider trading in a monthly market on a coup happening in Venezuela. The argument then was that such a market would barely function, because market-makers would assume that any trader in those markets had information the market-maker didn't. And yet, $30k of liquidity is a lot more than I'd expect to get on such an asymmetric bet. What that piece didn't anticipate was just how big prediction markets and recreational gambling would get. There are enough punters on geopolitical markets that liquidity provision can still work, and even if there aren't professionals involved in every market, those same recreational traders are still providing liquidity. On a platform that takes a cut of zero-sum bets, those customers are a naturally depleting resource, and if they start to view the markets as rigged, that churn will happen faster.

App Stores

The WSJ has a fairly negative review of OpenAI's early integrations with third-party apps ($, WSJ). They're finicky, and sometimes just add extra steps for the same process (apparently the Instacart one is fine). One difference between LLM-based shopping and other kinds is just how granular the data is. OpenAI just has a lot more context to understand shopping cart abandon rates than a website or app that's mostly tracking clicks and taps, in the same way that ecomm was able to collect more data about the shopping process than physical retailers could. It may be worth it to launch a half-baked product early and then fix whatever issues come up—one element of their data advantage is that if they launch a more seamless integration (like being able to book an Uber directly from the ChatGPT app instead of from Uber's), they can notify the users who've specifically run into that problem. If your customers are going to tell you what they think your product should be able to do, and if you can largely make that happen, then it makes sense to set yourself up to hear from them.

Gunboat Diplomacy

At some point over the weekend, Venezuela became a quasi US protectorate. Most of the time, taking over other countries doesn't pay off in financial terms—most of the productive assets are intangible, and losing a war tends to tank the value of those intangibles in addition to wrecking physical infrastructure. But in the case of oil, which is a globally-traded commodity, you really can make the numbers pencil out; opponents of the Second Gulf War referred to it as a war for oil, but the First Gulf War really was: Saddam Hussein invaded a smaller oil-rich neighbor. In the case of Venezuela, Trump has been pretty explicit about the role oil plays in his calculations, but there's a big gap between the always-dubious reserve numbers and the practical realities of extracting and processing heavy oil that's located inconveniently and whose infrastructure has been gradually looted over decades. To the extent that it's about oil, it's not about short-term supply but about long-term supply elasticity: a semi-stable Venezuela run by a US-aligned government that's friendly to American oil companies can, in future decades, respond to swings in global oil prices by adjusting supply to match. But for now, that's all hypothetical.

Liquid Content

Samsung's newest TVs offer, among many other things, a feature that uses AI to isolate different parts of the audio, so users can change the relative volume of background music, dialogue, and sound effects. This is part of the continuous unbundling of medium and message that AI enables. It will probably frustrate the actual movie industry to no end that viewers are casually undoing all the effort they put into getting the sound exactly right, but part of the broad history of the movie industry is that given the opportunity to consume in a format that's lower-quality but more convenient—a record rather than live performance, a transistor radio rather than record, etc.—enough customers will take it that the industry can't ignore it. And in this case, the supply chain from creator to consumer is so complicated that the creators don't really have a choice.

|