Heya and welcome back to Five Things AI!

There’s a noticeable sense of momentum around AI in early 2026, especially as conversations shift from what agentic systems could do to how they might actually fit into real organisations and workflows. At the same time, early signals around productivity are starting to move, adding to the feeling that something structural may be taking shape — even if it’s still too early to call it a boom.

Much of this excitement is still uneven and fragmented, but it feels qualitatively different from last year’s speculation-heavy debates. Instead of chasing singular breakthroughs, attention is spreading across process design, governance, and the limits of delegation. That shift alone suggests a maturing phase, where usefulness starts to matter more than novelty. Whether this momentum holds will depend less on models and more on how well organisations learn to work with them.

And is it just me, or are you also a bit worried when OpenAI announces new things, like for instance their foray into healthcare?

I’m adjusting the format of Five Things AI. Each week, I pick five articles from the past days that I think are useful for understanding where AI stands right now. Paid subscribers get my analysis and my perspective on the most relevant implications.

Enjoy this edition of Five Things AI!

The industry had reason to be optimistic that 2025 would prove pivotal. In previous years, AI agents like Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex had become impressively adept at tackling multi-step computer programming problems. It seemed natural that this same skill might easily generalize to other types of tasks. Mark Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, became so enthusiastic about these possibilities that early in 2025, he claimed that AI agents would imminently unleash a “digital labor revolution” worth trillions of dollars.

But here’s the thing: none of that ended up happening.

It’s the Gartner Hype Cycle in full effect. I am not the least bit surprised as we are struggling to get past the first excitement of what is possible to figure out what really works.

(…continue reading.)

In fact, I have great optimism that one potential upside of AI is a renewed appreciation of and investment in beauty. One of the great tragedies of the industrial era — particularly today — is that beauty in our built environment is nowhere to be found. How is it that we built intricate cathedrals hundreds of years ago, and forgettable cookie-cutter crap today? That is, in fact, another labor story: before the industrial revolution labor was abundant and cheap, which meant it was defensible to devote thousands of person-years into intricate buildings; once labor was made more productive, and thus more valuable, it simply wasn’t financially viable to divert so much talent for so much time.

Will we turn into a really, really productive society soon? Or will we just barely increase productivity as we let the AI agents do some work so we have more time to watch reels?

(…continue reading.)

By saying “most all social networks,” he frames an industry-wide argument rather than one specific to Instagram. Platforms may not like the optics of being seen as Temples of Truth, but they are already laying the groundwork for thatfuture.

He’s not wrong. This is no longer just an app design problem; it is governance work. The problem spans the internet,especially social networks. Meta does not want to shoulder this burden alone, for strategic, political, or legal reasons. The company recognizes that proof of reality is less a feature and more infrastructure built with camera makers, standards bodies, and other platforms.

So, wait, all of a sudden we have to rely on social media platforms to use their algorithms to protect us?

(…continue reading.)

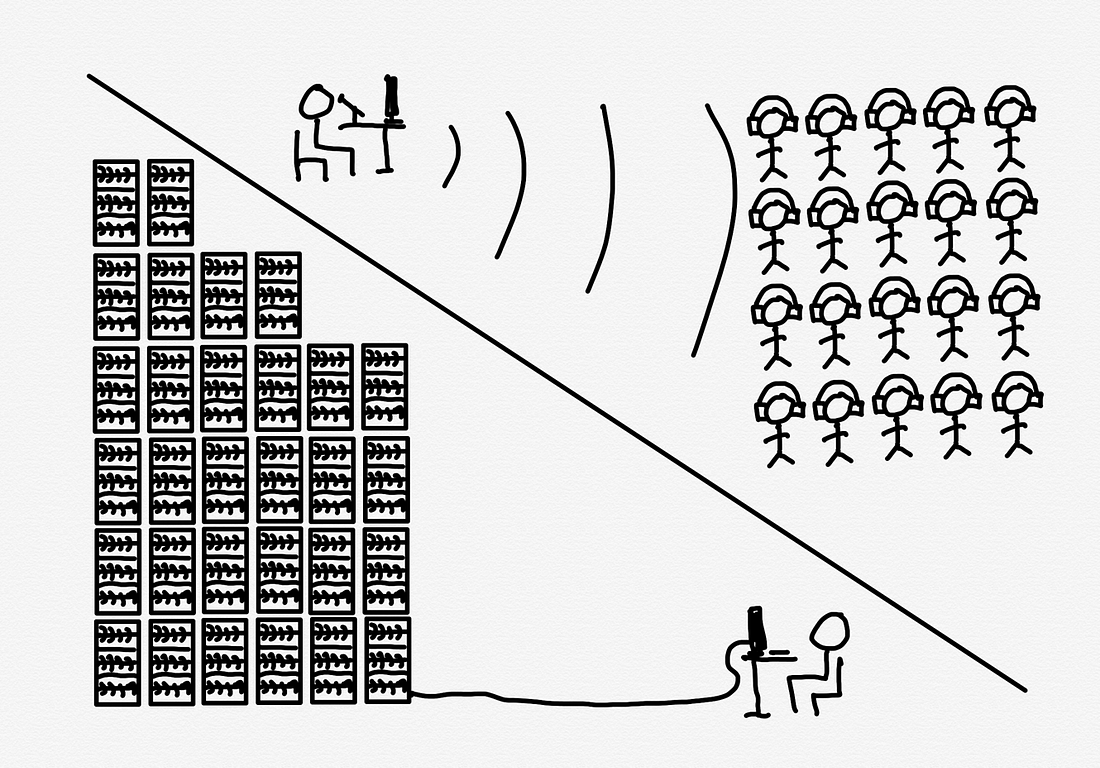

A key challenge is that for now the system only works on problems that can easily be checked, like those that involve math or coding. As the project progresses, it might be possible to use it on agentic AI tasks like browsing the web or doing office chores. This might involve having the AI model try to judge whether an agent’s actions are correct.

One fascinating possibility of an approach like Absolute Zero is that it could, in theory, allow models to go beyond human teaching. “Once we have that it’s kind of a way to reach superintelligence,” Zheng told me.

This is truly fascinating stuff and of course it seems totally odd at first, but it makes a ton of sense to train models like this to improve their reasoning capabilities.

(…continue reading.)

A crucial lesson I’ve learned is to avoid asking the AI for large, monolithic outputs. Instead, we break the project into iterative steps or tickets and tackle them one by one. This mirrors good software engineering practice, but it’s even more important with AI in the loop. LLMs do best when given focused prompts: implement one function, fix one bug, add one feature at a time. For example, after planning, I will prompt the codegen model: “Okay, let’s implement Step 1 from the plan”. We code that, test it, then move to Step 2, and so on. Each chunk is small enough that the AI can handle it within context and you can understand the code it produces.

Well, that’s what I figured out in the last four weeks of exploring Google Antigravity, which to me is really an amazingly powerful tool, that allows me to pluck together code to build something useful. More on that later.

(…continue reading.)

Continue reading to get my take on which two of these Five Things AI mean the most for you and us in 2026! You don’t want to miss it! ...