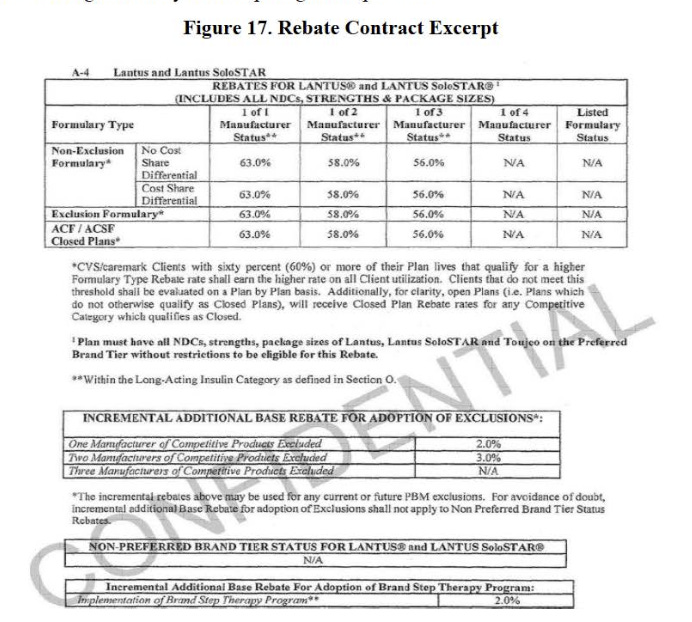

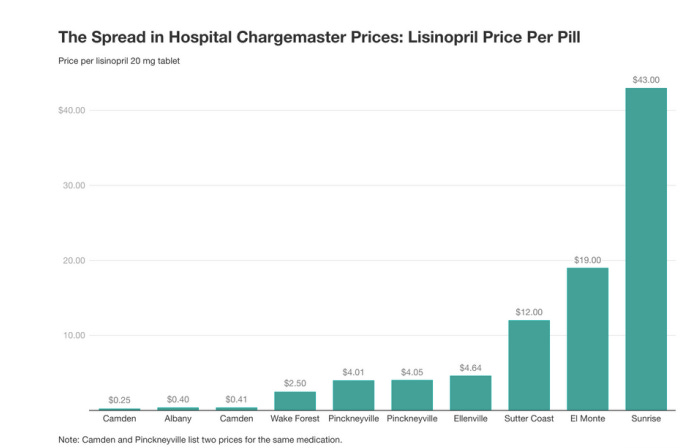

The One Simple Thing That Makes the U.S. Economy UnmanageableWe used to be able to answer the question "How much does that cost?" But prices in America are not only high, but increasingly hidden. Fortunately, there's pushback.In 1956, CBS launched a new game show, The Price Is Right, in its daytime schedule. Contestants were presented with various objects, and the one who guessed closest to the actual retail price would win. The Price Is Right became the longest running game show in American history, because it spoke to a very casual yet deceptively important social question: How much does it cost? There’s an important political assumption behind that question, which is that every retail item has one single price. And any buyer anywhere in America can pay that price to acquire it. Americans might have had different amounts of money, but they were all equal in that they paid the same amount for the same good. While a single price in a market might seem a natural state of affairs, and economists love presenting simple supply and demand curves assuming as much, there’s nothing natural about it. In fact, a dense network of laws and norms created the notion of a single price for all buyers and sellers in a market, aka, The Price Is Right society. We no longer live in such a society, because the legal framework behind a single public price for an item has fallen apart. There are many examples, but the easiest way to understand this change is to look at health care markets, where hiding prices, and the consequences thereof, is most advanced. There Are No Real Prices In Health CareA few days ago, Hunterbrook, a short-seller funded media outfit, released an investigative report showing what looks like a multi-billion dollar money laundering operation by the three largest health insurance companies. The allegation is that CVS, UnitedHealth Group, and Cigna are supposed to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for lower drug prices for their patients. But instead, they collude with those pharmaceutical companies to force higher drug prices, and split the profits with them. It’s not a new charge. The Federal Trade Commission included this alleged scam in its complaint filed against these companies in September of 2024.  The details of what Hunterbrook reported are complex, but the problem boils down to something very simple. There are no real prices in most health care markets. You couldn’t play The Price Is Right for medicine, because there is no actual one price for anything. The allegations involve the three main middlemen in drug pricing, which are known as pharmacy benefit managers. PBMs are basically payment networks with a negotiation function attached. They manage what drugs insurance companies cover, negotiate with pharmaceutical companies over the prices for these prices, and organize the copays of patients and reimbursements to pharmacies. But since the 2000s, a wave of consolidation means there are just three big ones, each of which is owned by a big insurer. They are Caremark (CVS), OptumRx (UnitedHealth Group), and Express Scripts (Cigna). And all three use their privileged position in the middle of the drug payment network to engage in price discrimination - charging wildly different prices for the same item - to direct revenue to themselves. Take, for instance, Gleevec, a miraculous blood cancer drug invented in 2001 that is now off-patent. As the FTC showed, if a patient of one particular insurer using a particular PBM went to Costco, it was $97, if that patient went to Walgreens, it was $9,000, if he/she got home delivery, it was $19,200. That’s three entirely different prices for the exact same medicine. Why? Well, the PBM allegedly received kickbacks based on the price of the drug, so it got more money if the drug cost more. “We’ve created plan designs to aggressively steer customers to home delivery where the drug cost is ~200 times higher,” wrote one executive. The mechanism PBMs use to foster these different prices is something called a rebate. An insurer will “pay” the list price of a drug, say, insulin. But then the PBM will negotiate a rebate from the pharmaceutical company of something between 40-65% of that list price. Here, for instance, is an old rebate contract for Sanofi’s Lantus, a popular branded insulin. Sanofi has to pay a 63% rebate to one of the big three PBMs, CVS Caremark, in return for which Lantus is the only insulin offered to Caremark customers. So what does Lantus cost? Well, the list price for Lantus was around $500, but the amount going to the pharmaceutical firm that makes Lantus was much lower. What happens to the difference? The PBM would pass some of that back to the patient, but keep some of it for itself. And the patient would pay a copay based on the much higher list price amount. This dynamic makes little sense; PBMs are supposed to save customers money by negotiating lower pharmaceutical costs, not just keep that money themselves. But that’s what they were doing. Eventually, this behavior sparked a backlash, and states started passing laws against keeping rebates. So PBMs embarked on a public relations campaign, saying they would reinvent their business models to pass the entire rebate back to their customers. What the Hunterbrook story shows is that they didn’t do that. They just renamed those rebates “fees” and paid those “fees” to different subsidiaries with different names than the one negotiating drug prices. Those subsidiaries are set up in tax havens like Switzerland, have very few employees, and yet manage to make enormous profits. If you’re curious, CVS’s new subsidiary is named Zinc, UHG’s is Emisar, and Cigna’s is Ascent. It’s all very complex, intentionally, and it’s designed to confuse people into not understanding what looks like a shell game. PBMs don’t just play games like this with Gleevac, they do it with lots of drugs. While the PBM scheme has its unique wrinkles, the basic behavior is how everyone in health care who has power operates. They keep their prices hidden. Take hospitals, which all together are around a $1.5 trillion a year sector in America. As part of Obamacare, hospitals were required to release their list of of “standard” prices for various goods and services, what is known as a “chargemaster” list. You would think that would end price secrecy in that sector. But no. Obamacare was passed in 2010. Fourteen years later, in 2024, the Government Accountability Office reported that hospitals are still not fully releasing chargemaster lists. And even if they did adhere, the legal requirement is only for list prices, not actual prices after various rebates. The result is what you’d expect. Here’s a chart of what different hospitals give as their list prices for Lisinopril, a heart medication. We’re not talking about a few percentage points, the changes are up to 10,000 percent different depending on where you are being treated. And there are many other markets in health care where this takes place, from hospital supplies to drug wholesalers, costing hundreds of billions of dollars. The History of “How Much Does That Cost?”And that gets us back to The Price Is Right. We’re used to thinking about price as something like a price tag, meaning that the cost is public and the same for everyone. A tube of toothpaste on the shelf at Walmart has a price on it, and that’s what you pay. There is some variability, that toothpaste might be slightly higher at another store, and people can use coupons. But for the most part, anyone can buy that same toothpaste for a similar price. The legal framework around pricing in America is fairness. Federal law bars “unfair and deceptive practices,” as well as “unfair methods of competition,” but even back to the earliest of colonial times, there was legal pricing standardization around milling. But price tags themselves are a relatively new innovation, roughly 150 years old, invented by evangelical business magnate John Wanamaker. Before Wanamaker, shoppers haggled with merchants, and paid based on relationships and power. It was a more localized economy, so fairness was inherently embedded in closer relationships, but pricing for giant systems, like farmers shipping over railroads, were highly contested and political. People understood the power of pricing, and how it let those who owned the highways of commerce control business. In the late 19th century, Grangers and populists demanded an end to rebating practices by railroads, because they understood that the ability of a railroad to price discriminate among customers could consolidate a market and crush ordinary business people and consumers. Oil drillers saw it as well. John D. Rockefeller used price discrimination to build Standard Oil, using his buying power to force railroads to give him rebates based on what his rivals shipped, and thus roll-up the industry. Over the course of the early 20th century, populists and merchants eventually forced an end to price discrimination, passing a host of laws to prohibit rebating and other forms of corruption within supply chains. Railroads, trucking, shipping, and airlines had strict rules against price discrimination. This tradition continued when the government entered health care. In 1972, Congress passed a law prohibiting kickbacks and rebates in Medicare and Medicaid. A key mechanism to uphold the integrity of price was to prohibit conflicts of interest among agents meant to represent buyers and sellers. The Robinson-Patman Act, for instance, doesn’t just bar price discrimination meant to monopolize, it also prohibits paying commissions to brokers by anyone except the business that broker is meant to represent. To draw an analogy, imagine if a lawyer you hired to represent you in a lawsuit could also take money from the person you were suing. We all know that’s unethical and would lead to your lawyer undermining your interests. That’s the kind of situation in commerce these laws were meant to address. With both posted prices and an end to conflicts of interest through rebates and other kickback-style games, anyone could participate in markets, and size and power were neutralized. Posted prices was just how we did things in America. And it wasn’t just game shows showing that consensus. Posted pricing had such powerful support that the 1980 Heritage Foundation’s Mandate for Leadership, the guidebook written by the conservative movement for the Reagan administration, supported it as well. The think tank attacked airline regulators for allowing a discount to a large buyer as “contrary to basic American precepts of justice.” They claimed that “selective price gouging, non-cost justified discounts for big customers, and secret rebates seems to favor the large organized interests with competitive alternatives at the expense of the unorganized, uneducated, or captive passenger.” Imagine that, the staunchest conservatives in the land felt strongly that prohibiting price discrimination was necessary for justice. That’s how powerful the question “How much does it cost?” really was. But then Robert Bork and the Chicago School revolution happened. Law and economics scholars made the argument that price discrimination was in fact good, and that conflicts of interest through vertical integration were efficient. They also claimed that price discrimination was progressive, allowing firms to charge more to the wealthy than the poor. Here’s what happened in health care markets.

What Happens in a Society Without Posted Prices?We’ve gone so far from posted public prices as the default that price lists are now often claimed to be proprietary and confidential information by dominant firms. Price secrecy and discrimination is most advanced in the health care sector, but the more we zoom out, the more we’re starting to see that there are fewer real prices in the American economy writ large. There are some significant implications here, aside from just having to pay more for basic goods and services. Without real public prices, having power in negotiations becomes a lot more important. And that’s an incentive to consolidate. For instance, last month, a judge forced the unsealing of an FTC complaint against Pepsi, which showed the soft drink maker was using secret rebates to allegedly collude with Walmart to inflate prices across the retail channel. The goal for Walmart was to keep a “price gap” of Pepsi products between itself and rival stores who might want to discount to attract customers. When a supermarket cut consumer prices on a Pepsi product and made itself cost competitive with Walmart, Pepsi would raise wholesale prices of that product to force that supermarket to stop discounting. What Pepsi got in return was to block rival soft drink producers from Walmart shelves. Walmart was so big that Pepsi couldn’t say no, even if it had wanted to. In other words, it’s a quid pro quo among giants, a consumer packaged goods company gets to be king in their realm if it helps a retail giant remain king in its realm. Because of the secrecy of pricing and the price discrimination involved here, the incentive to consolidate is irresistible. One of the reasons that supermarket giants Kroger and Albertsons sought to combine was to become as important to suppliers as Walmart is, so they could get some of these same kinds of discounts and compete. But there’s a lot more to the problem of secret pricing. Without public prices, attempting to figure out how to reduce costs becomes impossible. Last week, for instance, the Inflation Reduction Act’s pharmaceutical negotiation provision finally kicked in. Along with nine other high priced popular drugs, the list price of blood clot medicine Eliquis fell, in this case by 56%. That sounds good, right? Unfortunately, the “list” price isn’t real, there are always secret rebates off of that price to every payer in the system. The list price of a drug is similar to a department store showing dresses that are always 80% off - we know that the dresses aren’t actually meant to be bought at the original pre-discount price. Now, the cut in list price is probably good. What patients pay out of pocket is linked to the list price, so seniors will end up paying $1.5 billion less in cost sharing. But is there actually a reduction in the amount paid overall? Or is that $1.5 billion showing up in higher premiums? We don’t really know. So how can anyone figure out whether the IRA actually “worked?” Pricing secrecy also fosters massive waste. Hospitals and insurers now have compliance and billing staff in a Spy vs Spy contest to fight with each other, which adds up to big numbers. We spend $1 trillion a year just on health care administrative costs, which is $3000 for every American. And it’s not just health care. America now has a big set of administrative agencies known as “consulting firms” dedicated to extraction. Last October, I did a podcast with New York City’s new consumer protection chief Sam Levine, and we discussed his report on the McDonald’s Monopoly game. The Monopoly game used to be a fun way for kids to enjoy McDonald’s, but today it is about collecting data on customers so the company can figure out which ones will pay higher prices. What is striking is how much technical and managerial talent had to go into this kind of venture. Think of all of that waste, all those talented people spending their time trying to find surreptitious ways of raising prices on unsuspecting consumers. The lack of pricing may even be an explanation for why the economic statistics look so good to economists, but feel so bad to the public. The Consumer Price Index, the main way that we measure inflation, is partly based on surveys of public prices. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has people employed as price checkers to go to stores and look at price tags. But as Dean Baker observes, when stores play games with prices, and the label on the price doesn’t match what customers pay, those price checkers will understate what people are paying. I don’t know how the BLS handles junk fees, surveillance pricing, subscription traps, tipping screens everywhere, and loyalty programs wherein every company, as Luke Goldstein notes, is becoming a bank. I wouldn’t be surprised if these pricing games are screwing up our economic statistics. The New Movement to Restore the Posted PriceConservative economist Friedrich Hayek noted that price signals convey information about wants, needs, and supply capability, far better than any central administrative apparatus ever could. So the lack of posted prices should bother everyone, left, right and center, because it means that market pricing is no longer how we organize our commerce. Instead, we are a society where large centralized institutions allocate resources, dictating winners and losers based on their ability to choose what everyone has to pay. But prices also fulfill a social function. Asking a friend or colleague, “What did you pay for that [product/service]?” is an important mechanism we as individuals use to figure out how to manage a complex society. Looking at prices is a way that entrepreneurs decide what lines of business to enter, and how investors allocate capital. Prices even help policymakers understand how to govern. Without posted prices, we are all blind to what is happening in America. Instead, we express a low angry simmering grumble, as the world around us seems mercurial, mysterious, and out of control. Fortunately, we have woken up to this problem. I now see people on TikTok angrily talking about the lack of price tags. There’s lots of reporting on pricing games, from Hunterbrook’s recent report to the More Perfect Union stories on Instacart to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s forcing of the government to unseal the FTC complaint against Pepsi. States are now starting to pass laws against unfair forms of pricing, led by California. And as I noted above, the Biden administration filed a case against the three dominant PBMs and how they manipulate the price of insulin. Fortunately, the Trump administration FTC is continuing it. That case is scheduled to go to trial on June 17th of this year. So we can expect fireworks to continue. Ultimately, one key way to restore fairness in America is to get back to an economy where anyone can ask, “how much does that cost?” AnnouncementsI’m introducing a new feature in BIG issues called “Announcements.” Since this newsletter is for the anti-monopoly movement, I want to start highlighting what you are doing and connecting you with each other. So send me job listings, interesting projects, new lawsuits, etc. Include ‘announcement’ in the subject line, and I will publish the relevant ones. I have two announcement today. The first is that boutique antitrust law firm Kressin Powers is hiring for an associate position. I really like Kressin Powers, so if you’re a young lawyer looking for a good job in the Baltimore/DC area, send your resume on over. The second is also job-related. I’m looking for a free lance reporter to do some work for BIG. If you’re interested, email me with your resume. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |