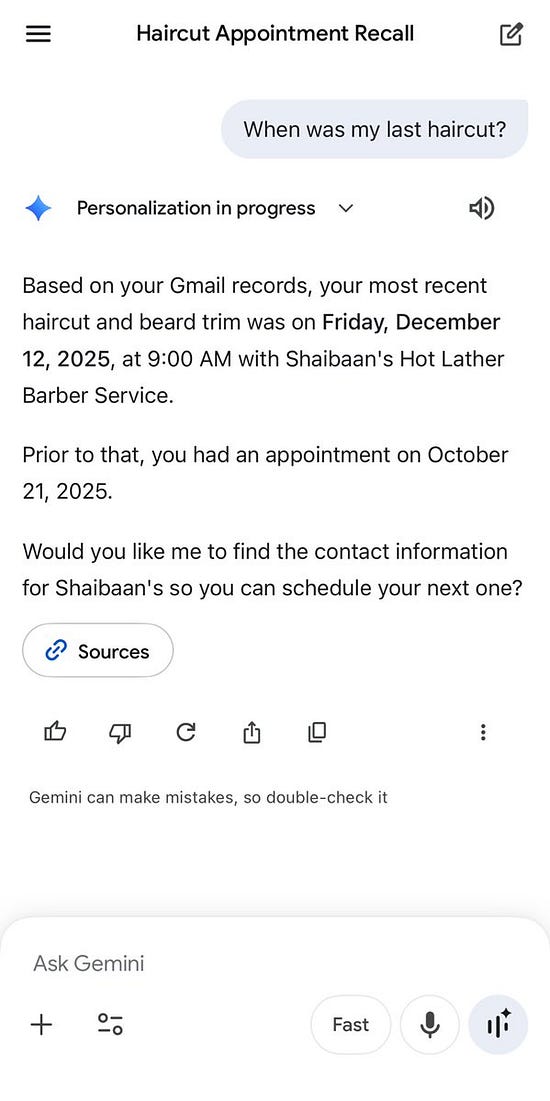

Will Google Become Our AI-Powered Central Planner?Google may monopolize the market for AI consumer services. And now it is rolling out a product to help businesses set prices, based on what it knows about us. The failure of antitrust will be costly.Earlier this week, Google made three important announcements. The first is that its AI product Gemini will be able to read your Gmail and access all the data that Google has about you on YouTube, Google Photos, and Search. While Google skeptics might see a Black Mirror style dystopia, the goal is to create a chatbot that knows you intimately. And the value of that is real and quite significant. Here’s venture capitalist and former Googler David Lieb on how he uses this new automated assistant. Google presented a number of different use cases. For instance, a user could “Ask Gemini to ‘Recommend tires for my car.’” and it can pull from your photos to “understand your car’s make and model, and even the types of trips you take” and thus make better suggestions. You might ask it to recommend travel destinations or books, or even haircuts. And Google will offer recommendations, along with products and pricing information. The second announcement is that Google has cut a deal with Apple to power that company’s Siri and foundational models with Gemini, extending its generative AI into the most important mobile ecosystem in the world.

The quality of AI is in part a result of data, so the ability of Google to use Apple user data is significant. Already Google, with its existing search, email, maps, online video, docs, auto software, and other products it can use to distribute and capture data, has advantages that make it almost untouchable. Its Gemini product is rapidly gaining market share in the generative AI market, similar to the trajectory of its search product in 2002. It’s increasingly an article of faith on Wall Street that Google has won the AI battle, and this Apple deal makes it unlikely anyone else can catch up. And the third announcement is that Google will launch a new Gemini-powered ad service and open protocol to create personalized surveillance pricing for merchants across the economy. It is, as Google VP Vidhya Srinivasan said, a way to “offer custom deals to specific shoppers who are ready to buy, without having to extend the same thing to everybody.” Partners include Walmart, Visa, Mastercard, Shopify, Gap, Kroger, Macy’s, Stripe, Home Depot, Lowes, American Express, etc.

Taken together, these three announcements imply a revolution about how our economy works. And Wall Street has noticed, with Google hitting a $4 trillion valuation. However, while the fight over generative AI generates a lot of chatter, there is one key question that we have to answer to understand its trajectory. How is Google Gemini going to make money? Right now, Google’s revenue stream comes from advertising via its search monopoly. Search queries are cheap, and the ads Google sells are pricey due to its market power, so it’s a very profitable business. Gemini, by contrast, is expensive to operate, and generates no revenue. Even if Google were able to shift all of its search advertising revenue to Gemini, it would be moving from an extremely high margin business to a lower margin one. So what’s actually going on? The answer, as it turns out, is that Google may be seeking to become our central planner and price setter. The third announcement is the key tell. CEO Sundar Pichai said the company will sell not only marketing, but price coordinating services. In the documentation for the universal commerce protocol, google lists “dynamic pricing” as a key tool for merchants. And Kroger, a partner of Google, already announced it will deploy Gemini, enriched with its own proprietary data, to do consumer pricing. Google is also creating a pilot of something called “direct offers.” Rather than just buying advertising, businesses will pay to allow Google set prices when it makes recommendations to users through Gemini. Here’s how Google presents it: “With Direct Offers, retailers set up relevant offers they want to feature in their campaign settings and Google will use AI to determine when an offer is relevant to display.” So for instance, as Gemini offers different tires to users based on its knowledge of their car and driving style, it could also offer different prices for those tires. Here’s a different example presented in Google’s marketing materials.

Marketers have allowed Google to automatically place ads under its own discretion for years, to pretty much run ad campaigns without that much input. But letting the search giant also run pricing strategies is new. There are many unanswered questions about how this new system will work. Right now, both Nike and Reebok advertise on Google, and it’s a little weird, because it means that each of them teaches Google how to sell sneakers, then rival sneaker companies can also hire Google to also sell sneakers. That’s not illegal. But if both of them give Google the authority to do pricing, then all of a sudden Google is coordinating pricing for sneakers, which looks much more like an automated form of price-fixing. There are several reasons to see what Google is doing as ominous. Pricing expert Lindsay Owens, who helped uncover the dynamic pricing scheme of Instacart, noted that this pricing engine could be a way of having Google help retailers analyze user data and then use it to “overcharge” consumers. Interestingly, Google responded by saying that its new service allows merchants “offer a *lower* priced deal or add extra services like free shipping — it cannot be used to raise prices.”

But of course, the idea that discounts mean lower price levels is foolish - just look at any health care bill from your insurance company, which often says something like the cost of an MRI is $8000 but the insurer got a $6000 discount and paid $1970, so your billed portion is $30. Obviously that $8000 number is fake, so is the discount, the only thing that matters is the cash changing hands. Pharmacy benefit managers get “discounts” off of ludicrously high list prices, but that’s fake. It’s like certain department stores who routinely mark everything as 80% off; we know that’s not a real discount. So I am worried when I see that Google is using the same rationale as PBMs, only for its new feature meant to change pricing strategies for the entire economy. More importantly, Google is explicitly saying it will use this tactic to increase revenue generated from consumers, to “help shoppers prioritize value over price alone.” There are other areas for concern. There’s no technical reason that Google itself has to be the centralized agent, presumably consumers could allow other generative AI models to analyze their data and become assistants. Just as Google’s search monopoly was not inevitable, neither is the Gemini takeover of pricing. What is ominous about Gemini is that for its monetization of Gemini to work, Google may have to eliminate market signals and democracy itself. And it has its marketing agents working on that point. For instance, Daniel Crane, an antitrust law professor and Google lawyer, wrote a 2024 article titled “Antitrust After the Coming Wave,” in which he discussed how antitrust law could not survive the inherent need to monopolize markets due to the characteristics of generative AI. He argued that we should forget about promoting competition or costs, and instead enact a new Soviet-style regime, one in which the government would merely direct a monopolist’s “AI to maximize social welfare and allocate the surplus created among different stakeholders of the firm.” When I see a Google agent making the case for this kind of centralized power, I take note. But the most important reason for concern is that Google has a long track record of structuring pricing choices, and an impetus to do so going back to its founding. In some ways, ideology and law is the most important force in markets, and so that’s where we have to start. Let’s go back to the original goal of Google to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” It took a long time to understand the importance and scope of this phrase. When I first heard it, the idea of organizing the world’s information sounded neat. Who doesn’t want everything organized? And what’s wrong with making information useful and accessible? In 1998, Google seemed cool, plucky, a challenging upstart, and the slogan “Don’t do evil” was sincerely held by the engineers at the company, who were the most prestigious people there. While it’s been decades since that founding esprit, one can still see the naive credulity on display as Google exhibits its new products, suggesting its sole goal is to help create a terrific AI-powered personal assistant. The early internet was full of this kind of rhetoric. Just two years before Google was founded, the influential libertarian hippy thinker John Perry Barlow at Davos had published the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. “Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel,” you “are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.” Barlow asserted a utopian vision of rights, free of government tyranny and entirely about voluntary association. It was a statement about law and democracy, as well as rights. Larry Page and Sergei Brin, the co-founders of Google, were part of this stew of libertarianism. They presented their search engine in a paper they wrote while graduate students at Stanford using money from a government grant, titled “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine.” This paper described their pioneering method of sifting through a rapidly growing web, known as PageRank, which ranked webpages based on how often they were cited by other webpages. It was then a fiercely competitive search engine space, but Google’s quality results blew away the competition, which was composed of companies such as Lycos, InfoSeek, AltaVista, et al. But an important aspect of their paper was ethical; Page and Brin believed that advertising was corrupting to the existing search engines on the market, reducing their quality and harming users. “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers,” they wrote. “Since it is very difficult even for experts to evaluate search engines, search engine bias is particularly insidious.” Page and Brin even had a framework to understand search and the problem of competition. While explicit pay-to-play for search results would generate outrage, they wrote, “less blatant bias are likely to be tolerated by the market. For example, a search engine could add a small factor to search results from ‘friendly’ companies, and subtract a factor from results from competitors. This type of bias is very difficult to detect but could still have a significant effect on the market.” But then Page and Brin took venture capital money to pay for their rapidly expanding search infrastructure, and hired the former CEO of Novell, Eric Schmidt. Schmidt had been a victim of Microsoft’s monopoly. He understood that a host of antitrust decisions in the period, including a bad D.C. Circuit ruling on Microsoft’s monopoly in 2001 and the Trinko case in 2004, suggested that monopolization was the right strategy for any firm, especially one like Google. In 2000, Google began accepting advertising on its search results. Google rapidly gained share in the search market, until it became a monopoly in 2002. Then it went on an acquisition spree. In 2003, the company bought Applied Semantics, which allowed it to do contextual advertising across the web. It acquired Keyhole (Maps) in 2004, Android in 2005, and YouTube in 2006. Its capstone acquisition was DoubleClick in 2007, where it became clear that this company was a dominant force. But just how dominant wasn’t obvious at first. In order for Google to organize the world’s information, it had to stop others from doing so. In 2006, Google encountered its first monopolization controversy, which involved a British comparison shopping site named Foundem. Foundem’s goal was to help consumers compare prices for different goods and services by creating a specialized search engine. Google was a general purpose search engine, but there were these kinds of “verticals” in lots of different areas, from local recommendation sites like Yelp to travel booking sites like Expedia and TripAdvisor. Foundem, like most web businesses both then and now, relied on Google to get in front of consumers. A few weeks after launch, Google downgraded Foundem’s site in its search results, claiming that comparison shopping services were spammy. But the creators of Foundem alleged something different to antitrust enforcers. They claimed Google killed their search placement and raised the ad rates the company had to pay to show itself alongside search results, but did so as a strategy to kill a nascent rival. They may or may not have been correct, but their logic was exactly that of Page and Brin in their original paper, saying that conflicts of interest in advertising-funded search were insidious. As Page and Brin noted, even experts had a tough time detecting corrupted results. What happened next suggested that Foundem had a point. After killing comparison shopping sites, Google introduced its own rival product, Google Shopping, which would help users find products when they searched on Google. Importantly, Google Shopping wasn’t a price comparison site. It was a way for retailers selling products to advertise on top of the Google search page, bidding against each other for better placement. Subtly, Google restructured competition in the consumer goods market to serve itself. Before Google crushed Foundem and the consumer comparison site industry, retailers competed by lowering prices to consumers, in the hopes of getting better placement by offering better deals. Afterwards, on Google Shopping, competition changed. Retailers had to compete for better placement not by lowering consumer prices, but by paying more money to Google for better ad placement on Google Shopping. Google, as far back as 2006, really was organizing the economy in subtle and important ways. (The fact that retailers couldn’t use marketing to benefit from lowering prices helped pave the way for Amazon to monopolize online retail.) Of course, this story isn’t just about technology or search, it’s also about law. And at the time, enforcers, especially in the U.S., were just not interested in addressing monopolization. The Bush administration didn’t believe in Section 2 of the Sherman Act, and while Obama’s people made some noises about it, they didn’t bring any cases either. So from 2002 onward, Google maintained its search monopoly without much legal concern. It faced a threat during the technology inflection point and shift to mobile, but quickly acquired a whole set of companies in the mobile space, and used political muscle to get a Federal Trade Commission investigation shut down in 2012. The European Union did investigate the Foundem case, but it took over a decade. In 2017, the EU fined Google 2.4 billion Euros over its abuse of dominance in this vertical. Google appealed, and in 2024, the EU version of its Supreme Court upheld the verdict. Of course, if the bad acts happen in 2006, and there’s a fine in 2024, well, all that shows is enforcers tacitly endorsed monopolization. Page and Brin laid out the conflicts of interest in their original observation of how search engines are funded. And the truth of their observation hasn’t changed. As it turns out, much of the early cyber-utopian rhetoric only seemed to be about liberty from government tyranny, but it was in fact hiding a form of private coercion in its seductive futurism. When Google discussed “organizing the world’s information,” few of us thought about prices as information. But they are. When Barlow said that governments are not welcome online, what he didn’t think through was how governments are also founded by human beings to promote justice against private acts of unfairness. And as we saw with Foundem, Google was organizing the world’s information in a way that didn’t include comparison shopping engines and low prices. Today, Google’s power is much more obvious. And it has been structuring markets for restaurants via maps, influencers through its recommendation and monetization systems, advertisers and publications via its adtech services, travel through its booking airline data hub, media content through YouTube TV, and so on and so forth. Perhaps the clearest place it does so is in advertising technology markets, where it controls the software platforms used by advertisers and publishers to buy and sell third party web display advertising. To manage this business, Google set up a quasi-financial market, where it served as the buying agent, the selling agent, and the exchange, and thwarts potential rivals who seek to disrupt auctions with better prices. The result has been the death of newspapers and publishers who rely on ad revenue. In this market, the problem wasn’t so much “how does Google get paid,” which was a monopoly fee on every transaction, but “whose interests do Google serve.” And the answer was arguably neither the publishers/supply side or the the advertisers/buy side, but Google itself. Meanwhile, by controlling the relationship between buyer and seller, website publisher and advertiser, small business and customer, Google could simply destroy those who didn’t want to participate in its ecosystem. So Google is quite experienced at structuring pricing. Unfortunately, we are in the midst of re-watching a Foundem-style legal flub, only this time with the entire economy. As Biden antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter noted, the emergence of generative AI is an inflection point, where we could move to a far more decentralized society, or end up with one that is far more consolidated. And we were set up to break Google’s power. In 2019, the company faced a real investigation over its various schemes to monopolize search, centering on its $20 billion of annual payments to Apple to prevent rival search engines from getting in front of Apple customers, as well as its control of Android. But as with the Foundem complaint, the controversy dragged on and led to very little. In 2020, the Antitrust Division filed a monopolization claim. Four years later, Judge Amit Mehta called Google an illegal monopolist in search, but in September of 2025, Mehta decided to impose virtually no penalties on the company. He didn’t even block the quasi-cartel between Apple and Google he had initially called illegal. The adtech problems drew a monopolization case, and Google lost that one too. And though the remedy is still to come, few think Google will be fundamentally restructured. And that’s a tragedy, because the shift to AI is perhaps more significant than the shift to mobile. As with the early search market, there are several companies offering foundational AI services, like OpenAI, Microsoft, Perplexity, Anthropic, DeepSeek, and so forth. The two key resources determining which model wins are, same as search before, data and distribution. Google, as you’d expect, is repeating its search monopolization playbook with Gemini. It is self-preferencing Gemini across its lines of business, which is what it did with Android and search. It is cutting deals to insert Gemini into every major retail channel, which is analogous to its payments to phone makers to thwart rival search engines. Then there’s its deal with Apple, which is virtually identical to what Judge Mehta found to be the original Apple-Google arrangement enabling the illegal monopolization of the search market. Mehta’s failure to impose a remedy was permission for Google to repeat this scheme with generative AI. And now it has. This deal will ensure that Google’s artificial intelligence chatbot product will become dominant in the most important mobile ecosystem in the world. And its experience structuring adtech markets suggest that if it mediates the entire economy, many tradition businesses will wind up like newspapers, eliminated as Google appropriates profit margins for itself and destroys the ability of consumers to differentiate products based on quality, innovation or other values. It could be an extinction level event for many commercial areas, like the death of the open web, and a dramatic narrowing of consumer choice. Are We Doomed?I am not a pessimist, so I don’t think we’re doomed. And I am painting a bit of a worst case scenario here. Perhaps Google is just trying to figure out how to make money with Gemini, and doing one small pilot. Perhaps its product recommendation and pricing engine won’t catch on. Maybe OpenAI can compete in the consumer AI market, or the Google antitrust case gets appealed and the remedy is overturned. And even if Mehta’s remedy is weak, it does exist, and perhaps some of the data sharing aspects of it can be useful. There are also a lot of interesting questions that we need to think through. Are Google’s partners making a wise decision jumping on the Gemini monopoly? Branded businesses have a reason to be wary of what Google is doing. When a business gives up its ability to price and directly connect to customers, it very quickly loses its viability. In the early 2000s, newspapers initially thought that Google was just selling low value remnant space they couldn’t monetize any other way, until Google devoured them with an illegal monopolization strategy. Is that recurring here? For policymakers, this moment of technological inflection suggests that the debates over big tech have shifted. Is there a structural conflict of interest in allowing Google to sell not just advertising, but price coordination services? Who is Google representing when it offers Gemini? The buyer? The seller? How should we think about price-fixing when AI models are opaque? What does reducing the power of big tech mean now that these conglomerates are integrating their lines of business with generative AI? What would breaking up Google look like? We really should have investigations and letters from members of Congress getting information on what Google and its commercial partners are trying to do. The reason these questions matter is because Google’s political position is weaker than it has ever been. First, the old Davos-style libertarian ethos that supported its rise is over. While there are disagreements about what to do about big tech, no one seriously argues that it’s not a political issue, that the emergence of these kinds of systems is inevitable and outside of politics. There are legal proposals to address the problem; Senator Ruben Gallego, for instance, a possible Presidential candidate, has proposed legislation that would ban personalized surveillance pricing. Second, even fellow oligarchs are afraid of Google. Here’s Elon Musk responding to the Apple announcement: “This seems like an unreasonable concentration of power for Google, given that the [sic] also have Android and Chrome.” And finally and most importantly, the public is angry about concentrated economic and political power. They do not like arbitrary and opaque pricing, and they will not tolerate a monopolist’s ability to wield it without limits. That is, of course, if we remain a democratic society. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |