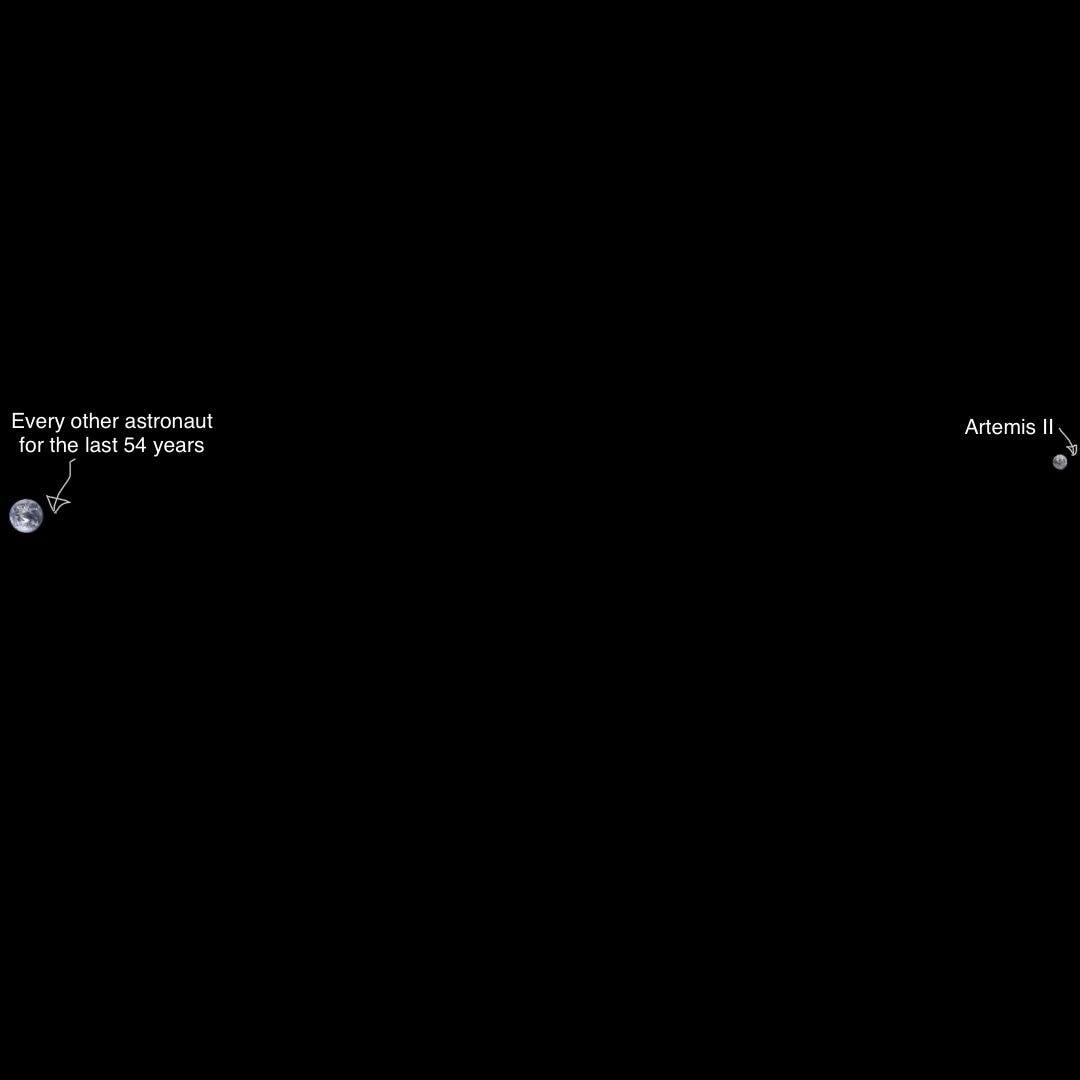

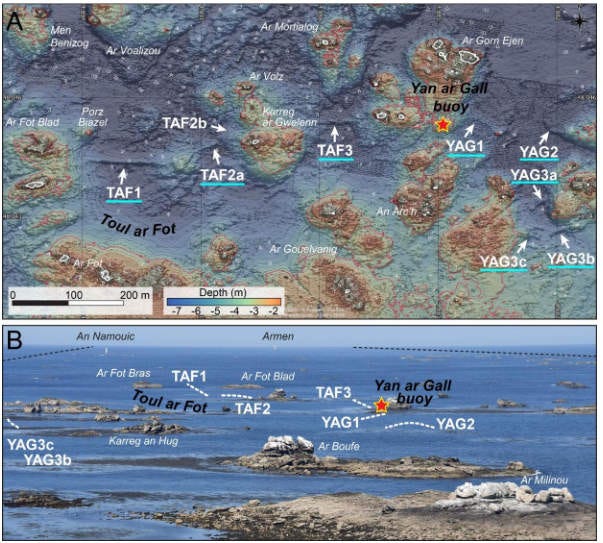

We're Going Back To The Moon And It's Kind Of Weird That Nobody Is Freaking Out?Plus: new stories of the ancient world, and an update on our planet's greatest navigator.Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about breaking science, applied curiosity and the endless joys of a good Wow. Before we begin: oh, this. So much this. I actually hadn’t twigged this properly until now. The last manned mission to orbit and land on the Moon was Apollo 17 in December 1972: Gene Cernan, Harrison Schmitt, Ronald Evans. To date, Cernan is the last human being to have walked on the Moon, on December 14th 1972 - when I was just over a year old. So yes, this is huge. I reckon we should all be talking about this (yelling, in fact) - and applauding the astronauts who are about to travel further from home than almost any living human being: (Yes, I said “almost”. The crew of Apollo 13 travelled the furthest distance from Earth - 248,655 miles - and of the three crew members, Fred Haise is the only one alive today, making him the current holder of the title of furthest-travelled person in world history.) Returning to ground level… As a BSc Archaeology student in the early 2000s, one thing I loved finding out is that scientific discoveries work in both directions. There’s the stuff that could dramatically change the future - this new cancer treatment, for example, discovered by scientists a few dozen miles away from where I’m writing this newsletter - and there’s also the new discoveries that expand upon or even overturn what we thought we knew about the recent and ancient past. It’s easy to misconstrue the importance of the latter type of scientific progress, and how newsworthy it should be. eg. Yes yes, but with everything going on in the news right now, who cares that Roman soldiers stationed in Britain were often laid low with the squits, or that there are the remains of a 90-million year-old rainforest under the ice of Antarctica? Firstly: have you seen the news right now? Perhaps a fascinating distraction from all that would be more than welcome? Secondly: what you need (and honestly, what news reporters need) is to get a skilled archaeologist to stand in front of you, maybe with a few pints of cider already in them, jabbering in wild but but super-articulate excitement about how profoundly this stuff matters. It’s been 25 years since I was one of those - and cider always gave me a headache, so I’ll stick with my glass of 12 year old Glenfiddich - but here’s my best attempt to do that for two recent stories you might have missed. 1. The Flooded Legend That’s (Maybe) Telling A Different StoryThe top image is an undersea chart of the sea floor around a series of rocky outcrops to the west of the French island of Sein, off the rocky shoreline of Brittany (the part that juts furthest westwards into the Atlantic). If you squint at where those arrows are pointing in the top chart, you’ll see some very unnatural-looking shapes. Particularly the one labelled TAF1, which runs in a straight line for 120 metres (400 feet). Upon investigation, this was found to be a 20-metre-thick underwater structure, standing metres off the sea bed: dozens of pairs of huge monoliths running in parallel lines just over a metre apart, with the space between filled with smaller slabs, angular blocks and scatters of pebbles. A wall, then, and a hugely substantial one - it’s not clear how deeply the monoliths are sunk, but they could be as tall as 3 metres. Then there’s the age of the thing. This is trickier than normal (no organic material = no radiocarbon dating), but two working hypotheses based on reconstructing the coastline based on changing sea levels suggest dates around the 5,500 BCE mark - making this structure upwards of 7,000 years old. This means it would predate the building of Stonehenge…by around the amount of time currently between us and the Roman invasion of Britain. (!) This puts it smack in the second half of the Northern European Mesolithic, when Doggerland to the north was fast disappearing under the sea, as I previously wrote about here: But Mesolithic people were hunter-gatherers. Their lifestyles were seasonal and mostly spent on the move! How on earth did they have the time and gather the resources to build stone structures weighing thousands of tons? In a way, all this is really doing is exposing how imprecise or even arbitrary our definitions of archaeological periods can be - it’s not like there were hard rules to what people could do within them (“non, you cannot build that there, François, it’s not the Neolithic yet”). What’s now regarded as “hunter-gathering” is obviously an incredibly varied range of behaviours, some of which might even be faintly recognizable in some people today. From this example, it’s clear that some coastal communities were putting a lot of time and energy into building permanent stone structures we’d now associate with a more settled lifestyle in more recent periods of prehistory. But [knocks back rest of whisky] where this gets really exciting is how this archaeology ties in with the local legends - the stories verbally passed from generation to generation, surviving long enough to be written down so they become an indelible part of the region’s cultural history. Half a dozen miles up the coast is the Bay of Douarnenez, widely regarded as the best location for the mythical city of Ys. If you’re a videogamer - yes, that’s where they got the name for the series (although everything else about the games is made up). The real-world myth of Ys tells of a fabulously wealthy settlement on the shoreline, protected from the rising sea with a series of enormous dikes. Every day at high tide these dikes were shut to protect the city - until one day, the king’s feckless daughter opens one to admit her secret lover, a mysterious, charismatic stranger (in some versions of the story revealed to be the Devil). Unfortunately she’s done so at precisely the wrong time in the tide cycle - and the sea roars in. The King leaps onto a horse, throws his daughter up behind him and gallops for safety - but then God intervenes, ordering the King to ‘throw off the demon on his back’. Promptly dumping his daughter into the floodwater (depicted above in a church window in Kerlaz), the King rides away to safety, as Ys disappears beneath the waves forever. The word to focus on here is “dikes”. If that’s what some of these submerged walls are (particularly TAF1), with smaller structures perhaps being weirs designed to trap fish, then it’s striking that their double-monolith structure is similar to many pairs of standing stones along this coastline dated to much later periods. This kind of continuity suggests a transmission of building knowledge across centuries and even millennia. How? Well - what better way than using a really thrilling, culturally resonant story?

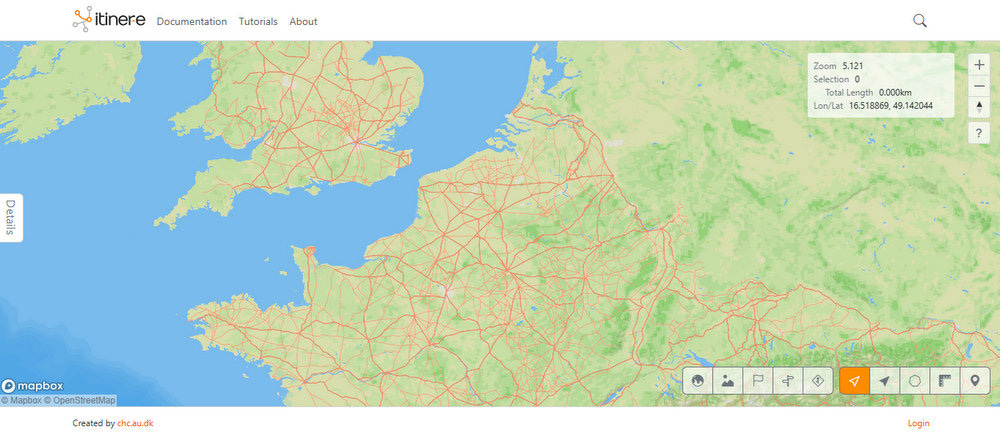

Without the presence of written records, archaeology usually has to rely upon the incomplete material traces of what ancient people did. To take that fragmentary physical evidence and build theories about what they were thinking, including what stories they told each other and why - that’s so much harder, often leading to a great deal of fascinating but wildly speculative theory (see: phenomenology). There’s rarely a direct, uncomplicated explanation that won’t leave your brain in knots, or turn first-year undergraduate students into hardened cider drinkers. But this? It’s obviously still a hypothesis, but what a stunningly elegant one, tying scientific evidence directly to mythology in a way that so rarely happens, while demonstrating the wisdom of dividing the study of archaeology into both the Arts and the Sciences, so they can cross paths under the same roof like this so spectacularly. Blimey. 2. An Empire Two Planets Rounder Than ExpectedThis is the circulatory system of the Roman Empire: the colossal road network across Europe and North Africa that allowed information, goods and armies to move around at a speed that could keep everything running for centuries. Only thing is: you’re currently seeing more roads than anyone’s ever known about, including Roman historians. If you could zoom in - which you can do here - you’d see all the minor routes, including highways between minor settlements, that previous studies have missed. This map (which I spotted via Jodi Ettenberg’s Curious About Everything) is the work of Itiner-e, a phenomenal integration of sources, including existing databases, satellite photographs and archaeological reports, into one big picture. And in doing so, it’s uncovered more than 60,000 miles (100,000+ km) of roads never recorded until now. That’s the equivalent of a single route wrapped more than twice around the Earth! But here’s an important caveat to all this from archaeologist and co-lead Tom Brughmans, via Scientific American:

(A fun memory I have here: a senior archaeologist telling me on a dig that since we knew for certain where a feature started and where it ended, it was my job to “draw a line between them” on the plan, suggesting I could “maybe make it wiggle a bit to look good.” Scandalous, yes, but sometimes an educated guess is the only way to keep things moving forward.) So, why is this important? Well - it’s a further insight into what it took to run an ancient empire. And as an exercise for your imagination, it’s like the world of Anno 117 has come to life. (I think Laura Kennedy will be a fan, based on this recent newsletter of hers.) But also? As someone who can’t get the thousands of miles of the Great Pangean Mountain Trail out of his head - this is far longer, and therefore a much more intriguing challenge. And it’s on roads! Far more walkable. Is anyone out there willing to do a Paul Salopek and devote themselves to walking every single proposed Roman road on this map within their lifetime, like William B. Helmreich’s epic quest to walk the whole of New York but on a vastly greater scale? And could it be me, please? (I know it can’t be, I’ve got too much to do, but - hey, can it?) BONUS!Remember when I wrote about the astonishing up-to-60,000-mile yearly migrations of the Arctic Tern, which they’ll do every year for the whole of their roughly 30-year lifespan? In the October edition of Scientific American, Lauren N. Wilson and Daniel T. Ksepka unpack the results of their studies in the Arctic:

But how many were migrating there, versus inhabiting the Arctic all year round? Wilson and Kspeka will continue to hunt for clues, possibly using isotopes in teeth or bones to infer the diets of animals and reconstruct their movements via a map of their food supplies. Yet it’s certainly possible that birds like the Arctic tern have been migrating from one end of our planet to the other for tens of millions of years - somehow encoding the detailed knowledge of those journeys to pass along to their offspring (“a genetic mix-tape of the memories of their ancestors”, I suggested here), and charting a course through our skies for vastly longer than our own species has existed… If we ever learn how to talk to birds, this is clearly where we need to start. Images: Itiner-e; Moreau.henri; HAL open science. |