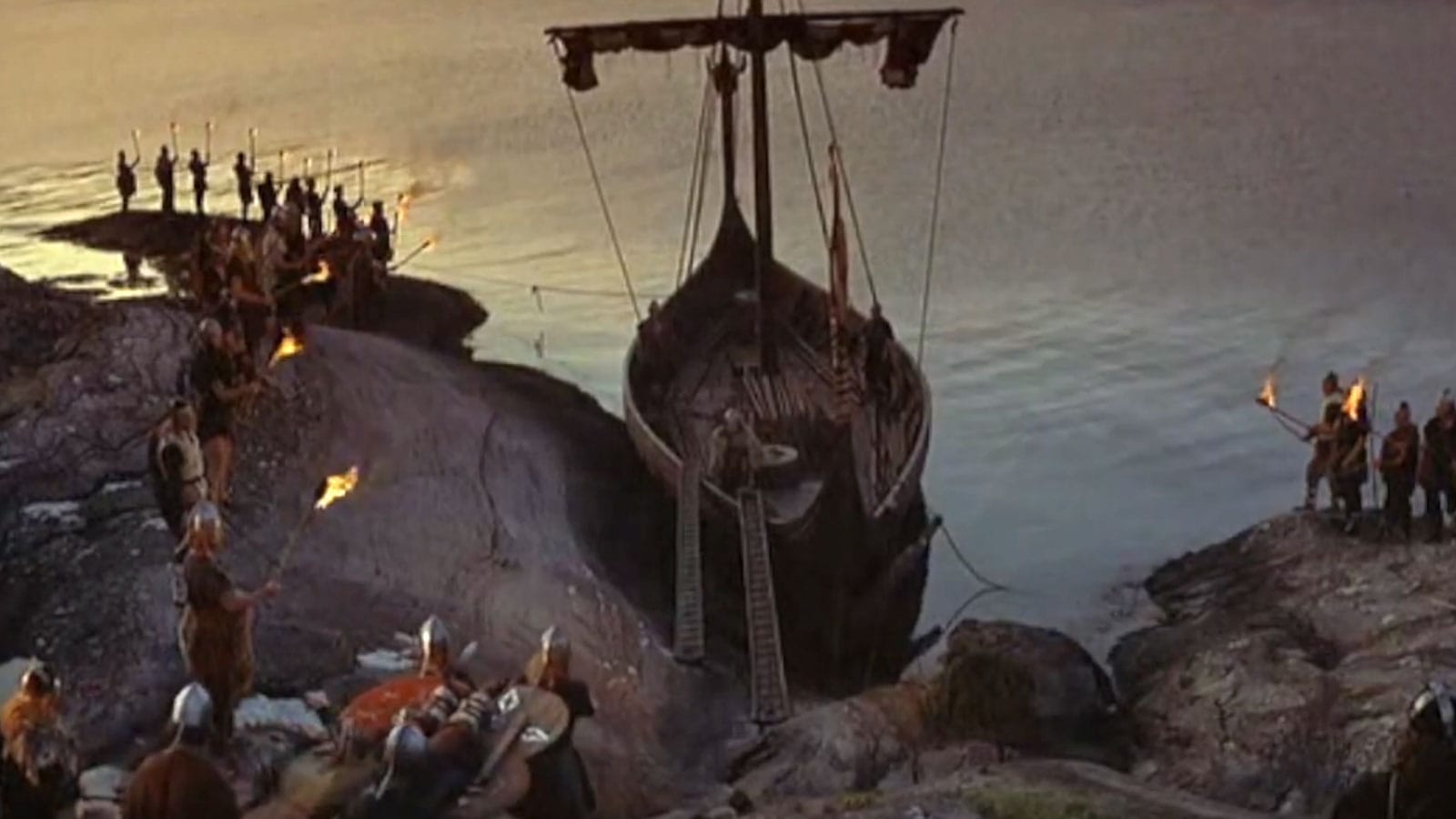

Screenshot from The Vikings (1958) via YouTube

Today: Anna Merlan, author of REPUBLIC OF LIES: American Conspiracy Theorists and Their Surprising Rise to Power; and Colin McGowan, a writer living in Chicago.

Issue No. 171The Viking Funeral Question

Carrie Frye A Glimpse of Robert Coover

Colin McGowan

The Viking Funeral Question Screenshot from The Vikings (1958) via YouTube A few years ago, my friend Anita discovered a highly particular lifehack, one which she has, in the spirit of generosity, agreed to share with the public. Without meaning to—without wanting to, really—she put a statement on her OKCupid profile that proved to be a magnetic force, drawing all the worst men in the world out of the woodwork so she could put them, tidily, into the trash. It wasn’t what you might expect. It wasn’t about religion, feminism, childcare, or Joe Rogan. It was, instead, about what she wants to happen after she dies; what we have begun to call, in our endless bemused texts on the subject, the Viking Funeral question. A little bit of context here, and some brief historical notes. At the time Anita started using OKCupid, anyone who viewed your profile could send a little inbox message, called an “intro,” in response to something you’d written and shoot their shot. Most men chose to send Anita the usual generic messages: “How was your weekend,” “Hi beautiful,” or, memorably, one guy who opened with, “I think I’m in love with you.” But a few responded to a prompt that Anita had filled in, asking users to complete the following blank: “When I die I will…” In response, Anita had written, “Hopefully have told enough people I want a Viking burial.” To be clear: when she wrote “Viking burial,” Anita was using the phrase to denote a historically incorrect but intensely cinematic idea; that her earthly remains would be floated onto a body of water in a tiny boat, which would then be burned—ignited from the shore by means of a flaming arrow. “Overall,” she explains, “I think that we societally use it ias a shorthand for a sea burial with fire. Although it's not historically super accurate.” Certain men of OKCupid were objecting to this, however, not on the basis of historical inaccuracy, but because they’d decided Anita was doing her death planning wrong. A remarkable number of them had this idea, and they flooded her inbox with tiresome regularity. “You might want to rethink that,” one characteristic message read. “I wonder what the permit situation would be like for a funeral pyre ship on the East River ; ) ?” remarked another. “Do you own a wooden ship?” yet another demanded to know. “A Viking burial? For a woman?” another wrote. “Too funny!” These men were so bothered—one might even say intimidated—by the concept of the Viking funeral that they forgot to hit on her. While some of the messages had the flavor of jokes, the overwhelming majority seemed, well, mad about it. (“Don’t you have to BE a Viking for this? I feel like they don’t just hand out Viking burials.”) Many of the same people seemed freaked out by Anita’s hobbies—she’s an archer herself, and has done wilderness survival training in the woods for two weeks at a stretch. (Once, after a long day of museum-hopping through the city together, she fixed me with a gimlet eye and declared, “I’m worried about you. It’s been hours and you haven’t peed once. You’re clearly dehydrated.” Reader, she was correct—and, moreover, was carrying a collapsible water bottle.) But then there were the men who seemed normal—normal enough, anyway—and they were the ones who didn’t want to tell Anita that her funeral plans were all wrong. They wanted to talk about something else in her profile. At one point, tired of overly personal questions about what she was “looking for,” she posted that she was looking for good swimming holes and a used 2002 4Runner. Surprisingly, every man who wanted to talk about cars turned out to be supremely normal and pleasant. The only real lesson here is that there is perhaps no area of life where certain men will not demand a say, or appear out of nowhere to tell you you’re doing it wrong. It occurred to me, as we spent literal years puzzling over these terrible and/or unhelpful responses (“To get a Viking burial you have to die in battle 🙂”) that it’d be a good idea to find your own personal equivalent, the question that immediately weeds out everyone who would be wrong for you. For me, it was when an ex casually declared he’d never let a boy child use a purse, and would punish the desire for a purse out of him. For others, it’s catching a glimpse at who they follow on Spotify. I had another friend who managed to weed out a great number of suitors during Covid by avoiding anyone who demanded a “pure blood” date. Obviously, holding a Viking burial isn’t without its logistical difficulties. There are questions of location and legality, and even the matter of whether the fire on a boat will burn hot enough to make an effective pyre. One death blogger wrote an engrossing piece about how our notions of how cool this ceremony would be are entirely influenced by Hollywood, starting with the 1939 classic, Beau Geste. Despite every obstacle, it’s also simply possible for a woman to know herself, funerary rites and all. If Anita should happen to die before we do, our friend group has found that we possess both the means and the willingness to make this happen for her. (Before a major surgery, a friend pinky-promised her that he would handle the arrangements.) If need be, I will do a little target practice and set the arrow loose myself. Those men were never necessary. One day, maybe, Anita will float on without them.

ELSEWHERE IN FLAMING HYDRATom Scocca has a phenomenal recap of the debate over at Defector.

A Glimpse of Robert Coover Laura Gilmore [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0] via Flickr The 92-year-old novelist Robert Coover likes a breathless, pages-long paragraph, fat with lists and layered metaphor, repetition, contradiction, bluster and refrain, puns, dialect, intricate and seemingly irrelevant detail, lanced with digressions—beginning with an em dash and progressing through thickets of clauses complicated by parentheticals, winnowing and broadening and branching like country roads or vascular systems or, come to think of it, speech and thought—the sense of which can escape you by the time you reach the end of a paragraph, leaving you to decide whether to work back through the grammatical algebra or just give yourself over to the velocity of it. This summer I read John’s Wife, a brutally horny Clinton-era survey of a nameless small town whose citizens whirl in the gravity of the titular John, a real estate developer who handpicks the mayor; operates an airport, a civic center, and several malls; is sucked off in the pilot seat of a plane by a Parisian artist who kills herself, in part, because she can’t have him to herself. The histories and longings of the town’s citizens are delineated in abundant detail, the chapterless and constant narration shifting between the perspectives of thirty-odd characters, but every situation is somehow informed or limited by John’s power. As for John’s Wife, who is never named, everybody wants to be or sleep with or kill her. It’s not what I’d call pleasure reading, but Coover’s prose has almost pharmaceutical effects on my mind. “The Creep’s mother, also Jennifer’s and little Zoe’s, once known as Trixie the go-go dancer and now as Beatrice, the preacher’s wife, had arrived at that party straight from church choir practice, feeling exhilarated.” Descriptions like this one are both helpful and exhausting. They’re also Coover’s way of tracing the fissures in the maybe-not-so-unified whole of an individual, in a maybe-not-so-unified town. In the book’s climax, everything comes apart. A posse composed of half the principal cast hunts a kaiju-sized woman in a burning forest. John’s business associate abducts a teenage girl and brings her to a cabin he and John use as a sexual retreat. A car dealership owner, double-crossed by his new wife, bleeds out in his garage. The language is rich in detail but still fragmentary and confusing. Like a camera with the zoom cranked, whipsawing in a storm.  The Public Burning, published in 1977 and perhaps Coover’s most famous novel, is a daffy satire of the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, narrated for long stretches by a fictionalized version of then Vice President Richard Nixon. It’s not a page-turner—on page 381, the story stops dead for “Intermezzo: Human Dignity Is Not For Sale: A Last Act Sing Sing Opera By Julius and Ethel Rosenberg”—but it does explain a distinctly Republican variant of Cold War paranoia exceedingly well. The narration, whether in Nixon’s voice or a more omniscient one, obsesses over the exploits of The Phantom, a geist of Communism that existed solely in the minds of blind drunk McCarthyites but nonetheless had very real effects on American foreign policy. It got people killed and immiserated many more. Coover’s skewering the pols and the Pentagon but he’s also channeling them, working himself up into their deranged lather. He filigrees the vast expanse of this historical narrative with ridiculous though plausible fabrications, the wildest of which is his staging of the execution of the Rosenbergs not at Sing Sing but in Times Square, in front of a roaring crowd. The effect of all this—essentially “We Didn’t Start the Fire (1953 Edit)”—is concussive, which isn’t totally a criticism. There’s something deeply true about it. The Cold War was, above all, really stupid. And America has maintained that stupidity ever since, like a plane at cruising altitude. The news is concussive, too. I’ve been reading Coover alongside reports of Gaza being flattened by U.S. bombs, during the coup within the Democratic party, while J.D. Vance failed even to order donuts like a regular person and Trump continued to intoxicate the GOP with avant-garde visions of misanthropy and race-hate. I wish I could say that any of this was edifying, that I was capable of refining this rancid raw material into important theories or, at least, healthy coping mechanisms, but mostly I have been scrolling and shivering, increasingly upset. Coover’s pummeling fiction articulates and activates this feeling. This would make him unbearable if his writing didn’t also contain sparer, slower passages in which he considers his characters not as actors in a broader plot or victims of societal turbulence but as they are when they’re alone, or reaching out to another person. The 1968 novel The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., is the story of a graying accountant named Henry who invents an imaginary baseball league where everything—hits, strikeouts, injuries, retirements, deaths—is determined by the roll of three dice. Henry has been playing this game on his kitchen table for several years. The league has accrued decades of history, most of which the dice can’t describe, so Henry has filled in the blanks himself, sketched a brotherhood of ballplayers who love and despise each other, struggle through hitting slumps and cheating wives and ulcers and sabotage from the league office. He has created a fully complicated reality. Most of the book is composed of a slow-burning psychic break Henry is suffering after the chance-divined death of one of his favorite players. Right before he descends into full-on mania, Henry gives living in the world one last try. For the first time, he invites someone else, his friend Lou, over to play the game with him. This goes as badly as it possibly could. Lou is well-meaning but uncomprehending. He’s been told that they’re going to play a game, and is disappointed when he discovers that he and Henry are going to spend the night rolling dice and recording their outcomes. Lou lacks Henry’s imagination and patience, and more important still, his deep investment in the game. When Lou drowsily upends a beer can over the papers on which Henry has written the game’s rules and rosters and statistics, the last of Henry’s hope and sanity vanish. “You clumsy goddamn idiot!” he howls, as Lou flees. “He stood, turned his back on [the game], feeling old and wasted. Should he keep it around, or…? No, better to burn it, once and for all, records, rules, Books, everything. If that stuff was lying around, he’d never really feel free of it.” Here is Coover talking about being a writer, how involving and pathetic and humiliating it is. Scenes like these, and there are plenty, emerge in his work like the outline of someone glimpsed through the all-white veil of a blizzard. They ring as true as his familiarly dreary, giddy maximalism because being in the world is upsetting and ridiculous and being with yourself is the same, but those experiences vibrate at different frequencies. Suddenly he’s no longer the thundering voice of god doing warehouse inventory, focusing instead on something specific and human, or something sad or funny or pretty. Maybe he’s even confiding in you.

Buy cool stuff and save the independent press!? YES.

|