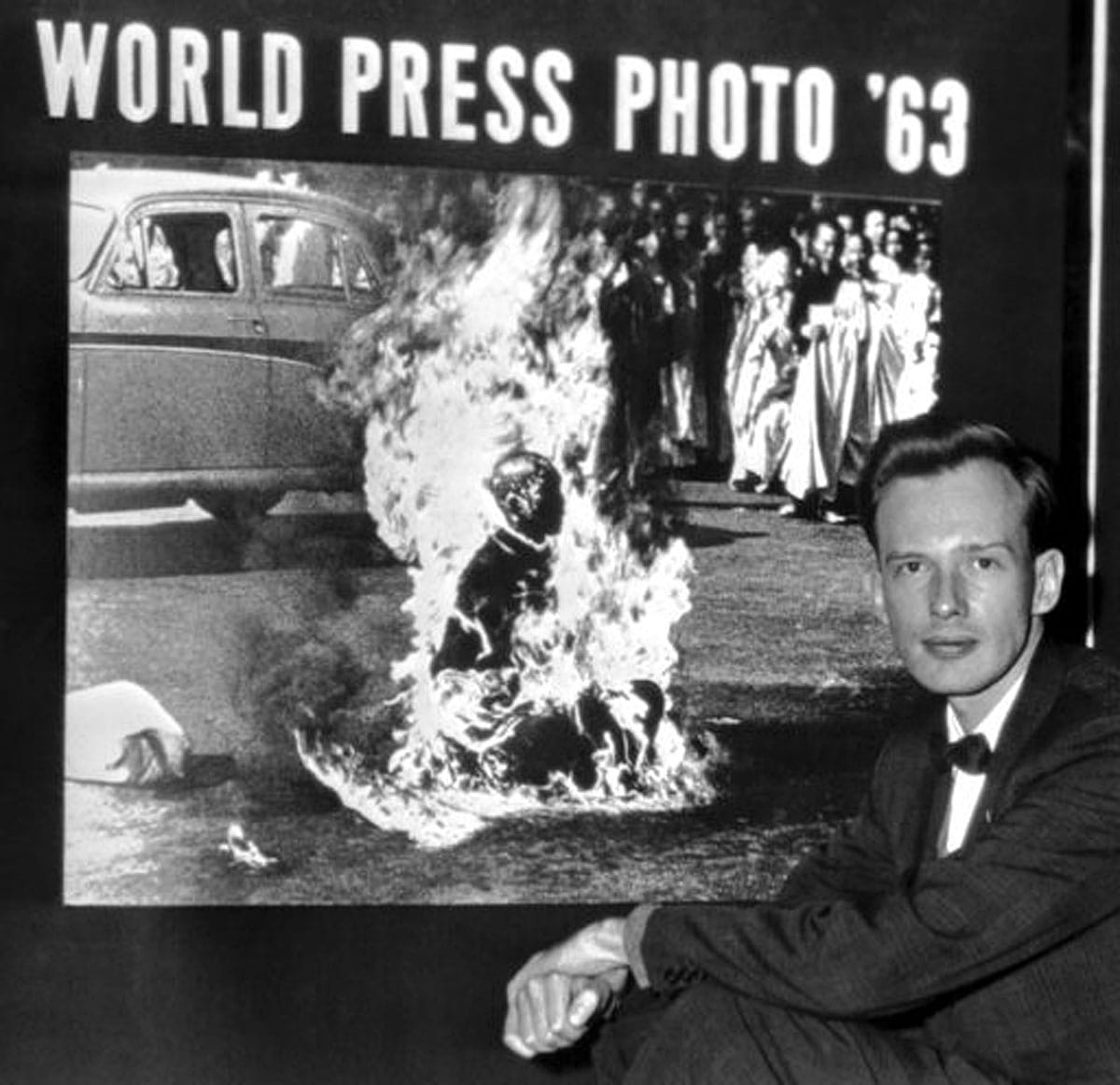

Malcolm Browne for the Associated Press, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Today: Sam Thielman, a reporter, critic, essayist, and editor, and graphic novel columnist for the New York Times.

Issue No. 172The Fires of Creation

Sam Thielman

The Fires of CreationThe earliest story of self-immolation that I know is in Sophocles’ Women of Trachis, in which Heracles enlists his son, Hyllus, to help him build the pyre upon which he prefers to die rather than let the blood of the venomous Hydra consume him. It is the only way he will find relief. “[B]e the healer of my illness and sole physician of my agony,” he begs Hyllus. In Ovid’s retelling of the story for his Metamorphoses, Hercules is burned half away, leaving only his immortal part. Meanwhile, all that the flames could ravage had been disposed of

by Vulcan. Hercules’ body no longer survived in a form

which others could recognize. Every feature he owed to his mother

had gone, and he only preserved the marks of his father Jupiter.

Metamorphoses Book 9, 262-265

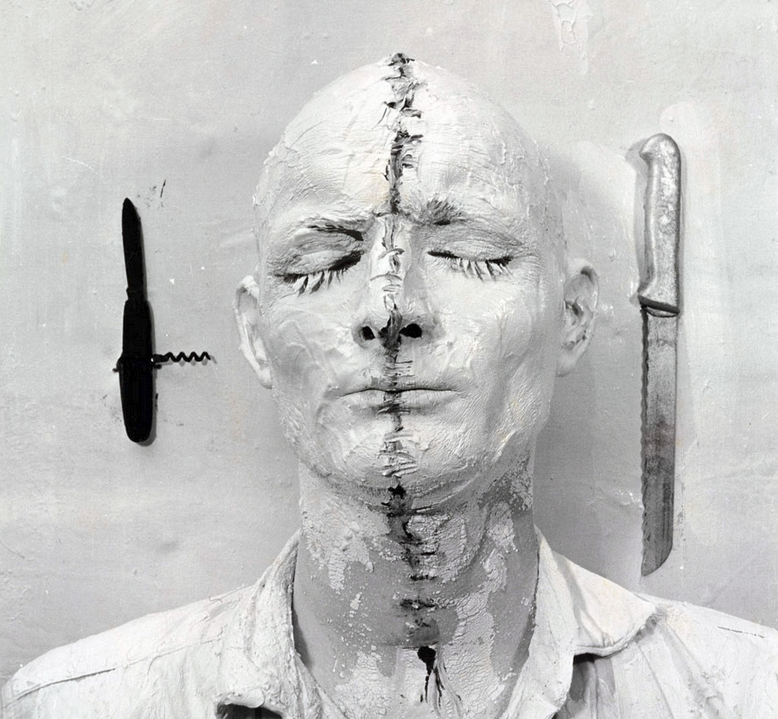

The poetry of Sophocles and Ovid is as close to immortality as an earthbound thing can be, in both cases investing the themes of self-immolation and defiance with appropriate solemnity and gravity, as in a religious text—just as Thích Quảng Đức made sure his last words were carefully transcribed and distributed before his death: “Before closing my eyes and moving towards the vision of the Buddha, I respectfully plead to President Ngô Đình Diệm to take a mind of compassion towards the people of the nation and implement religious equality to maintain the strength of the homeland eternally. I call the venerables, reverends, members of the sangha and the lay Buddhists to organize in solidarity to make sacrifices to protect Buddhism.” Đức was the Vietnamese Mahayana monk who set himself on fire in the middle of a busy Saigon street on 11 June, 1963 in protest of the persecution of the country’s Buddhist majority by U.S.-backed Roman Catholic ruler Ngô Đình Diệm. Many people have killed themselves in this way since then, in the declared service of causes both just and unjust, but of them, Đức’s image—captured in two perfect, unbearable black-and-white photos by Malcolm Browne—has remained perhaps the most indelible. In one of Browne’s pictures, the one that won a World Press Award, Đức is completely engulfed in white flames that form a zone at the picture’s center that is not even recognizably part of a photograph. The fire is a kind of blazing chiaroscuro over and behind the black of his charred skin, the borders between flame and flesh blurred with a quality one might find in paint or charcoal. In the second photo, probably best known from the detail used as the cover of Rage Against the Machine, Đức’s face, or the half that is visible, bears an expression of concentration. Flame burns white and black in his lap; perhaps the other part of his face is completely obscured, or perhaps it is already absent, boiled away into particulate and adrift in a pillar of white fire as large again as the man himself, carried up over his perfectly shaved scalp and into the crowd of horrified off-white onlookers in their light gray robes.  Image: manhhai [CC BY 2.0] via Flickr Two men died this February after protesting public complacency in the face of atrocity. One was Aaron Bushnell, 25 years old and an active-duty member of the United States Air Force. “I’m about to engage in an extreme act of protest, but, compared to what people have been experiencing in Palestine at the hands of their colonizers, it’s not extreme at all,” Bushnell told his phone before setting it down. He set himself on fire in front of the Israeli embassy on Sunday, 25 February, screaming—between screams that didn’t have words—“Free Palestine,” again and again. As he did so, the phone uploaded his death to his account on the video game streaming service Twitch, where the recording sat between broadcasts of ultra-realistic military shooters made with the cooperation of the U.S. Department of Defense, like Call of Duty: Warzone and Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Siege, until the service’s moderators removed it. As Bushnell’s video concludes, uniformed people can be seen frantically emptying fire extinguisher after fire extinguisher at his burning body while one of their number stands foolishly by with his gun drawn, ready to unload it, too, into the dying man, should the need somehow arise. The video was disseminated on Twitter/X, initially by reporter Talia Jane, who—at the request of Bushnell’s loved ones—added a blur that obscured the destruction of Bushnell’s body once it began to burn. Footage also made its way to YouTube—and then back to Twitter/X, and to Twitch—in less-censored form and festooned with salacious cautionary text: “very, very graphic,” “viewer discretion is advised,” “may contain suicide or self-harm topics,” and the omnipresent suicide hotline number, displayed in responsible proximity. There is no way to make this video into something other than what it is: An image of a man dying before your eyes in real time as a way of emphasizing his command to you, the viewer, to free Palestine. There is no version of the video in which Bushnell fails in his task, or screams something different. It would be obscene to try to make such a thing. The record is not the act, but it is vitally important to the act’s effectiveness, which is measured in attention paid. The Atlantic’s Graeme Wood pleaded with readers to “Stop Glorifying Self-Immolation” in an article published shortly after Bushnell’s death. I would suggest, respectfully, that it is a bit late for that: the act, as Wood himself observes, speaks to a kind of ultimate sincerity; the glory, at least initially, is in the blaze.  Günter Brus, Self-painting I (1964) via artblart.com The other notable February death was of the Austrian artist Günter Brus, who, having been briefly ill, passed away surrounded by family at the age of 85. Brus was born in 1938, when Germany annexed Austria, and he devoted his life to railing against the elements of Austrian and German cultures that had accommodated themselves to fascism before the war and allowed veterans of the Nazi military and its occupation regime to remain prominent in polite society. When he was thirty years old, Brus and the artists he worked with, the Viennese Actionists, attended a student gathering at the University of Vienna where they performed the Austrian National Anthem while vomiting, defecating, and jerking off. Brus peed into a glass, and then drank from it. He was arrested and tried for the crime of desecrating a national symbol. (The anthem, not himself.) Some of the Actionists staged elaborate and gory tableaux for photographs and films, but for Brus, staged violence was insufficient. In 1970, he performed his final Action, called “Zereißprobe,” literally “breaking test;” you can see gelatin silver prints of Klaus Echen’s photographs of it at MoMA, but several minutes of the performance itself can also be seen in grainy video uploaded, predictably, to YouTube. In the video, Brus has cut himself and beat himself. Blood runs from his scalp down his back. He appears to be passing a sewing needle and thread through his own skin. The idea of the mutilation of the human body, and the attendant shock and repulsion that is hardwired into us not just as people, but as mammals, is the point of much of Brus’s work. No simulacrum of injury, or pain, or debasement would accomplish the artist’s goals. It must be the thing itself. “It was so unbelievably palpable, how these Nazis were everywhere, on every corner, much more than the police,” his wife Ana Brus told the New York Times in 2018. Günter, in the same piece, offered a frank appraisal of his work’s effect on that society: “My art doesn’t just stink in the physical space but smells in the souls of the people,” he said. (Indeed, the offense Günter offered was so rank that the Bruses nearly lost their children to the state. Günter was imprisoned once and, after continuing to provoke the Austrian right, forced to emigrate rather than face a second, longer term.) Other artists have found Brus’s example instructive. The Russian artist Pyotr Pavlensky sewed his mouth shut at a public event to protest the incarceration of the anti-Putin band Pussy Riot. In 2013 he nailed his scrotum to a paving stone in Red Square. That same year he appeared, wrapped in razor wire, in front of the Kremlin. He was exiled to France for setting fire to the doors of the Lubyanka, so he set fire to the windows of the Bastille instead. Brus believed that if people witnessed his personal self-mutilation they might be moved to consider crimes like the Holocaust in a similar, more immediate frame than they did the lies of the Austrian establishment. This rationale is identical to Pavlensky’s, and to Aaron Bushnell’s.

Much of the coverage of Bushnell’s death has so far employed the language and inflection reserved for people who have killed others, not themselves. “[H]ow a young man who liked The Lord of the Rings and karaoke became the man ablaze in a camouflage military uniform remains a mystery, even among some of his closest friends,” murmured the Washington Post. (Again: He died screaming “Free Palestine!” at the top of his lungs.) The Daily Mail ran a perfunctory and irrelevant condemnation of its favorite usual suspects—Shaun King, Jill Stein, Cornel West, and so on. Dozens of “Who was Aaron Bushnell?” articles sprang up, just as they do after every mass shooting. In South Korea, Tommy Craggs observed in March, “[e]very martyr seems to beget their own bureaucracy of posthumous care,” but here we have no such structures. Our protest suicides throw themselves on the mercy of history. As smartphones have proliferated and social media has connected civilian populations to war zones, all have witnessed the accretion of atrocity images, available at whatever resolution strikes your fancy. We are far enough into this new visual history of conflict that the images themselves are no longer novel; in many cases they are pressed into service by propaganda operations seeking to gin up sympathy for their cause in completely unrelated conflicts. The news agency Bellingcat now recommends using public database Camopedia to make sure that the uniform on a soldier committing a war crime belongs to the army being accused. Pavlensky and Brus and Bushnell and Đức all chose to harm themselves, which protects the images of their suffering from that kind of corruption. But suffering alone cannot prevent those images from losing their context over time. Only life, lived properly, can do that. Brus, it seems to me, could easily have killed himself as a final, dramatic Action. Instead he chose to live and to continue to speak out, even when he could no longer use his own body as a stage to enact the kind of suffering he hoped to stop in front of the people he believed could stop it. It’s foolish—not to mention pointless—to condemn Aaron Bushnell or Thích Quảng Đức. They deliberately placed themselves beyond condemnation, cleansed in a fire of their own making. Those of us who are left must find ways to live with that.

Will not last: a spectacular original painting by Hydra Yemisi Aribisala, at our Swag and Archive Project fundraiser.

|