Pieter Lastman, Jonah and the Whale (1621), public domain

Today: Jennie Rose Halperin, digital strategist and librarian at NYU's Engelberg Center on Innovation Law and Policy; and Miles Klee, author of the novel Ivyland and culture writer at Rolling Stone.

Issue No. 177Jonah and Erica and the Whale

Jennie Rose Halperin Animal Control

Miles Klee

Jonah and Erica and the WhaleOn Rosh HaShanah this is written; on Yom Kippur this is sealed; how many will pass from this world; how many will be born into it; who will live and who will die; who will reach the ripeness of age, who will be taken before their time… who by earthquake and who by plague; who will be tranquil and who will be troubled. But through return to the right path [teshuva], through prayer [tefilah] and righteous giving [tzedakah], we can transcend the harshness of the decree.

Unetaneh Tokef, stanza 4, Mishkan HaNefesh)

At the concluding service on Yom Kippur, Erica and I read the story of Jonah in front of the congregation, a tradition we started shortly after our bat mitzvahs and continued through high school. By the end of the day at our Reform synagogue, the number of people had usually dwindled, and the Haftorah portion was the only thing standing between the community and break-the-fast kugel. The only person still listening was Sol, an elderly religious man who went to every service and sat in the front row. Erica and I were childhood best friends who had drifted apart as teenagers, but we still felt close, and the holiday gave us an excuse to hang out. After the service, we would take a plate of food to our former Hebrew school classroom where we’d learned the story of Jonah, though neither of us remembered learning anything in Hebrew school at all. In the portion, God tells the Prophet Jonah to warn the people of Nineveh to repent of their “evil ways” to avoid destruction. But Jonah knows that God would never be so merciless and also hates the Ninevites for some reason, so instead, he sets sail for Tarshish with some friendly sailors. God promptly attacks the ship with a storm in order to force Jonah complete his divine mission; the sailors cast lots and figure out that Jonah is to blame for the storm, which he admits; reluctantly, the sailors throw him overboard. Jonah is famously swallowed by a big fish (whale) and is stuck in its belly for three days and three nights. Within the whale, Jonah faces death. He experiences hell on earth, reporting that “the bars of the earth closed on me forever.” But then, through the eyes of the fish, he sees visions of the Holy Temple, and he receives God’s light like “two glass windows” (in the telling of Rashi). Based on these visions, and at the end of his rope, Jonah himself repents of his earlier disobedience, begs for death, and is vomited (“spewed”) out. God’s voice commands him yet again, and this time Jonah returns to Nineveh, where he succeeds in turning the people from their evil ways without much trouble. He preaches the need for repentance, and they fast and wear sackcloth, even putting sackcloth on the cattle. Jonah leaves Nineveh, an “enormously large city,” after his speeches and walks east. But he quickly becomes distraught; saving the Ninevites was too easy! It was not worth the brush with death, so he asks God to die yet again. God responds by making a plant grow over Jonah’s head for shade and comfort, and then quickly destroys the plant with a worm. Jonah, still tortured, sits in the hot sun and becomes faint, begging to die once more. God reminds Jonah that he cared about the shade plant, which he had not worked to cultivate, and which grew and died overnight. Should God not likewise care about Nineveh, filled with more than “a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not yet know their right hand from their left, and many animals as well!” Even taken solely as a narrative of faith and redemption (teshuvah), I find the story of Jonah deeply strange and unsettling, the central character selfish, the story brutal and surreal. It’s unclear whether Jonah finally decides to do as God asks because of his conscience, or just because he is just tired of being tortured—preaching repentance is a relatively easy task, after all, in comparison with being trapped in a giant fish. And Jonah says repeatedly that he does not actually want to save the people of Nineveh; he is coerced into repentance, and angry when the city is saved. He trusts in God enough to deny his divine mission, but he also fully believes he will die inside the fish, which means the people of Nineveh will die as well. When I am feeling more generous, I understand Jonah’s anger as frustration over the inequality of his lot. He’s the one who has to go through hell, while the people of Nineveh only have to wear sacks, fast, and atone, an echo of the traditions of Yom Kippur. Jonah runs from his destiny, but the God he runs from is ultimately forgiving. That forgiveness enables the potential for evolution, both for Jonah and for the people of Nineveh. But it’s the final comment, about the relative importance of things in the world, that’s most hopeful to me; it is usually translated to say that the 120,000 people of Nineveh do not yet know their right hand from their left. There is hope that someday they might—that all of us might. Life might be hard and unfair and full of bullshit, but trust and forgiveness inspires change, while selfishness and stubbornness breaks the will to live and rips apart communities. Erica overdosed at 28 from fentanyl-laced heroin, alone in a suburban basement. Shortly before she died she had been posting constant warnings about a Trump presidency on her Facebook wall, screaming into the digital ether. It wasn’t exactly prophecy, but addiction had caused her world to narrow. Her social media became her public legacy, though she also left behind a trove of stories, poems, comic essays, and personal narrative. She was thrown overboard, but no God came to rescue her. She remained stuck in the belly of the whale, trapped in a dark emptiness that never gave way to teshuvah. In the wake of her death, Erica’s friends and family endowed a scholarship for young writers in our hometown. Every year, her name will be repeated and her story told, even if she didn’t make it off the ship, or out of the belly, or ever find shade from the desert sun. Merciful God or no God at all, I miss her every day. And from the depths of the bottoms, when the earth closes its bars, I hope she can still see the world through the eyes of the fish, like two glass windows onto the world.

JOIN FLAMING HYDRAS ON BLUESKY Come on in, the water’s fine As we mentioned yesterday, Flaming Hydra is trying out a new feature on Bluesky called Starter Packs—custom-made mini-networks of people you can follow with one click. Here's where you can follow all the Flaming Hydra writers on Bluesky, all at once. We find this to be a fun social media vibe, like the good part of the olden time. If you’re on Bluesky and you’d like to be part of a Flaming Hydra Subscriber Starter Pack, please write to hello@flaminghydra.com and tell us your Bluesky handle. We’re setting up a new starter pack with the first 50 subscribers who respond. There’s space left but not a lot!

Animal Control Pesotsky [CC BY 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons\ The following is an excerpt from The Last Year, a longer work of fiction currently in progress. The previous chapter is available here. “What do you think of the phrase ‘he took his own life’?” I’m asking my most trusted coworker, Alison, the manager who brought me into the company, and with whom I share many weaknesses. She is not directly my boss, although not not my boss, a fact that charges our somewhat flirtatious friendship with a lively dose of risk. “Oh, it’s a little fucked up,” she says. “It romanticizes the act.” We drop the subject as more people collect behind us in line at the coffee shop. It is something fine to be at that stupid, bland cafe, a chain that ranks below the very successful chain: we value that anonymity. This location is around the block from our office, which in a part of town that none of our friends have ever visited, a short distance from the marina, the sailboats and their silly names. “Dennis Wilson drowned in the marina,” I say outside, stirring the crushed ice in my cold brew. I never let them give me a lid. “He was swimming off a yacht.” “So he killed himself.” “Or took his own life.” Alison turns to glare at me — it’s sexy as hell — and sips her drink through a paper straw, pinched between forefinger and thumb. I am pushing it on a Monday. “It’s considered an accident, of course,” I say. “He may have taken his own life, but how is it our job to figure that out? He made it impossible to know. I’m aware of what the phrase is meant to do. It makes it sound like they were still in control. I have my disagreements with that language.” She steers us left out of the strip mall, away from the office. “Dennis was the one hooked up with Manson.” “That’s right.” “I would guess that he killed himself, intentionally or not. Though ‘took his own life’ is better than ‘he died by suicide.’ Isn’t that how it’s written now?” “Framing it as a disease.” “Which it is.” “So what’s wrong with putting it that way?” “Just listen to it,” Alison says. In the office, I circulate, trying to get a read on anyone’s computer display. A couple hundred employees, maybe five of whom are assigned to work I understand. I pass the woman who last year at the holiday party got so drunk she announced that she wanted to fuck me, and has, from what I can tell, no memory of this: she toils at some kind of graphic design, her gaze almost unfocused. I also take note of the web developer guy who has his adjustable desk permanently elevated for standing, and brings for lunch every single day —even on those occasions when the company serves us tacos or pizza or some catered buffet—an obscenely large tupperware packed with shredded red cabbage. “How does he eat that,” Alison writes back when I message her about it from twenty feet away. “I don’t think it’s even seasoned.” “Well, I don’t know that I’ve seen him eat it,” I write back. “We have to consider the possibility he brings it in and throws it out every day. What if his partner packs it for him and he’s just pretending, to humor them?” “You’re an idiot,” Alison types, giving me a pleasant rush. “He wouldn’t need to pretend to us. He could dump that slop on his way in every morning instead of showing it off on his standing desk. We’re all meant to see it, and feel guilty for eating trash ourselves.” When Alison and I do eat lunch—that is, when we don’t skip eating—we like to go with the art team to a Thai restaurant where beers are two dollars at midday. Or to another coworker’s nearby house where we bring our own beers, and a small heated pool and Ethiopian takeout and sometimes a little pile of cocaine are waiting for us. These afternoons are dreamlike, an absurd loophole in the business to which we are all servants. Today, however, we are occupied with shampoo. Our employer, a shaving razor brand recently acquired for a ghastly sum by a multinational conglomerate, now aims to expand its line of bathroom products, the kind marketed explicitly to insecure men so that they need not suffer the embarrassment of using feminine-coded soaps and scrubs. They must be made to see that cleanliness is strength, that proper hygiene is a top concern of the alpha male. Which is why our new amber-and-lavender shampoo is a problem. What kind of advertising copy will transmute this flowery scent into a source of studly vigor? How can we make it sound as if, by washing his hair with this, he takes on the aura of a professional rock climber or Fortune 500 CEO? We have sat in frigid conference rooms squirting the stuff into our hands, to assess its color and texture and, of course, the silken smell, then cleaned our palms with paper towels and wet wipes. It is an enormous waste. The brainstorms have always fizzled. Our best pitch is really more of a joke: some kind of military-industrial tie-in, an ad where a special ops commando treats himself to a luxurious shower in his barracks after another successful raid. (On a whiteboard, the word “tactical” is underlined.) No, we have no ideas, we cannot help these men wash their hair, we may as well go for an early, boozy lunch. A scream erupts from the other end of our hangar-like warehouse office. Alison and I spin in our chairs, lock eyes, and stand up to look over the open floor plan. The woman who propositioned me at the holiday party is running away from her desk toward the data team, the nerds watching her nervously. “Squirrel!” she screams at them. “Squirrel!” “Nice,” says our deputy art director in his stoner drawl, not shifting the computer from his lap. “Thing probably has rabies. Tuck in your pants, everyone.” The neighborhood squirrels have become significantly more aggressive, creating an ongoing drama: certain employees are feeding them, while others protest that squirrels are disease-carrying rodents. A recent email thread on the topic became so heated that a product manager swore she would start leaving poisoned food on the patio, a vow that may or may not have resulted in a call to PETA from a pro-squirrel employee who insists that the squirrels are harmless, various reports of bites notwithstanding. Sure enough, one squirrel has grown bold enough to invade the premises: we all laugh as it skips through the field of desks, even scaring the little chihuahua that spends its days dozing at the feet of our IT chief. Then the fire alarm goes off, and everybody groans. “Can’t say I mind the vape break,” Alison says out on the street, though she brazenly vapes in the office as well. Easily half the crowd is puffing away. “Are they actually going to kill it,” I wonder aloud. “We can’t exactly wait for a squirrel to take its own life. Why’d you even bring that up before? So morbid.” “Sorry, it was dumb,” I say. “But not this dumb.” “Most of us are getting fired next month,” she says. Another pull on the vape. “Don’t tell anyone I told you.” “At least we had a bad run. Should we grab a drink while animal control secures the area?” “I started AA this weekend.” “Wow,” I say, “that’s cool.” “You have no idea how many celebrities are at these meetings. By the way, how’s the divorce?” “I’m not about to take my own life, if that’s what you mean. Found a legal workshop that can guide me through the paperwork for a few hundred bucks.” “You know, I’d be a great divorcée. It’s not fair you have to get married first.” There’s more laughter as multiple firetrucks and ambulances roll up to the curb. My admirer from the holiday party is sitting against a hedge on the sidewalk, slightly hyperventilating, and accepting the words of comfort from colleagues of the anti-squirrel persuasion. I could have sworn that workplace politics once held a deeper significance, but maybe I’m just remembering TV shows. An hour after the evacuation, we’ve had no updates, and I decide to beat the rush hour traffic home. Except rush hour starts at 2 p.m. and there is no beating it. A long while later, on the home stretch of La Cienega, a black BMW ahead of me swerves into the next lane, cutting off a beaten silver Honda, which accelerates as the driver leans on the horn. The Honda chases the other car to the next red light; then this driver, huge and pale and bald, steps out of his vehicle, walks up to the driver’s window of the BMW, and shatters it with a jab from his right elbow. The BMW tries to escape by running the red, but the Honda driver sticks his head and arms into the shattered window and wrenches the wheel to the left so that the car starts to pull a U-turn with him running alongside it. With a sudden burst of acceleration it completes a circle and T-bones the idling Honda. I take the next right, driving east, away from the scene and into the safety of smaller streets. I could have been the one who carelessly offended that Honda driver, and come face to face with that monumental rage, gotten myself hurt or killed. I did not agree to share a world with these people. I’ll be unemployed in a matter of weeks, I’ll have too much time and no money to enjoy it. Not that I’ll miss the company. In fact, I’m already free of the shampoo conundrum. I turn up Dennis Wilson’s “Pacific Ocean Blues” and roll the windows down.

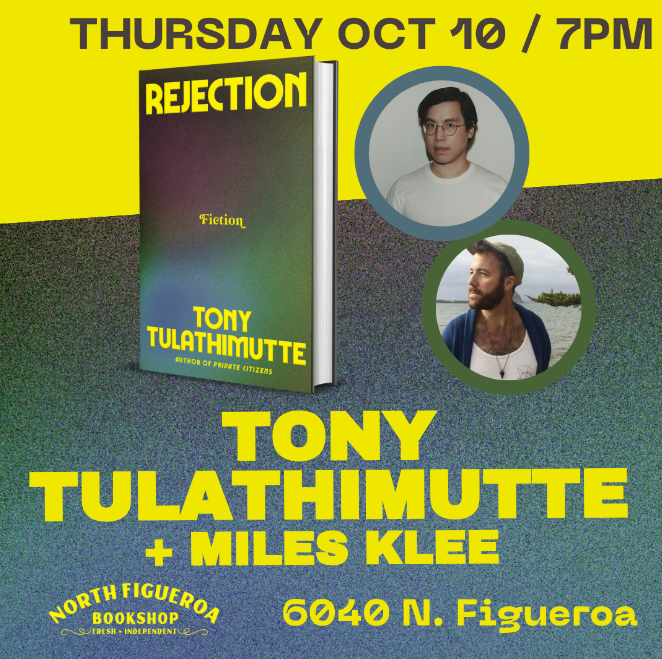

FLAMING HYDRA IRL Hydra Miles Klee TONIGHT in conversation with Tony Tulathimutte at the North Figueroa Bookshop in Los Angeles In Los Angeles? Ready for some fun? Join Hydra Miles Klee at the North Figueroa Bookshop where he'll be in conversation TONIGHT with Tony Tulathimutte, author of REJECTION.

6040 North Figueroa from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

|