Image courtesy of the author

Today: k.e. harloe, a freelance writer based in New York, author of the newsletter media x capital and the column Mediaquake at Popula.

Issue No. 198What Friends Are For

k.e. harloe

What Friends Are ForTwice this year, I found myself posting email away messages declaring family emergencies. In neither case did my messages tell the truth. The first was in February. A friend, whom I’ve known for almost ten years and lived with for four, had a psychotic episode. I’ll call him L. In addition to this friend, I also live with his partner, T. The episode came on fast, like a thunderstorm, on a Sunday. We began the trip to the hospital early Monday morning; parents set off from various cities and states to meet us. Life’s labors were quickly divided among this small group of people. Group chats formed and emergency lists made. I ordered lunch, texted updates to the chain, and emailed L.’s professors. T. returned a call from a nurse and then a doctor. T.’s parents did the dishes. Has anyone contacted so-and-so? It went on like this for a while. Continuously, I found myself lacking a vocabulary for the situations I found myself in. Standing in the hospital room with L.’s partner, parents, and doctor: Who was I, exactly? I’m his roommate. Notifying bosses or teachers: I’m his friend. Finally, when putting up an away message on my work Gmail, I cut to the chase: I’m out of office due to a family emergency. It wasn’t true, but I knew it was the only phrase that—without excessive elaboration—would communicate what I needed.

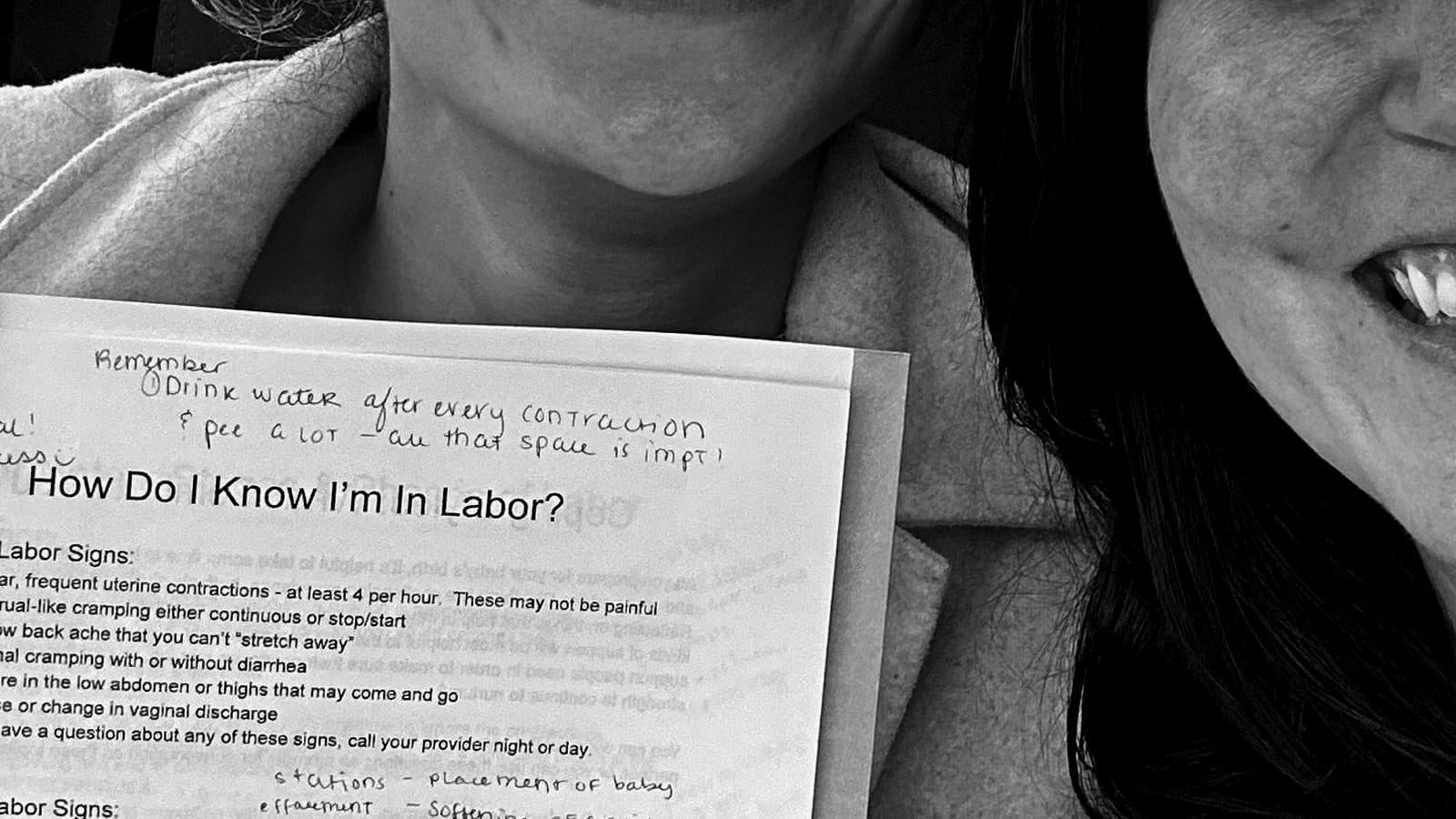

The second time came in September. This time, a different friend—I’ll call her M.—called me from a hospital room in a neighboring state: her water had broken five weeks early and could I travel to her today? Earlier that year, M., who does not have a romantic partner, had decided to get pregnant and asked me to be present for the birth. I attended her first sonogram; I participated in the birth classes; I talked to many mothers. I have never given birth and I expect I never will. (I have never wanted to.) I felt excited and moved to be so close to M.’s experience. In the end I spent about eight days in M.’s city: visiting and delivering food to the hospital; talking with nurses, doulas, and doctors; preparing her home for her return, and the baby’s arrival; coordinating care for her goldendoodle; and so on. I’m a freelance writer so it goes without saying I’d have no kind of parental leave, even if whatever role I was occupying in this situation had been legible to others, let alone the legal system. This time I wasted less energy; as soon as I received M.’s first call, I put up an away message: I’m out of office due to a family emergency. In between errands, chores, and doctor visits, I filed my taxes, made calls from cafes, and took meetings from the hospital restaurant. I used the shorthand liberally: in texts and calls and appointment cancellations, I said I was having a family emergency and I’d explain later.

After M. gave birth, I was surprised to find myself far more fascinated by pregnancy, birth, and parenthood than I’d ever been. In terms of my own desires, nothing had changed: I still felt certain I didn’t want to give birth or have children of my own. But in terms of my curiosity, something had changed: I now had a nearly insatiable desire to read and think about the topic. M.’s baby was born around noon on a Sunday; that night, I arrived home and ordered half a dozen books. A few days later, while reading the introduction to Rachel Cusk’s memoir about motherhood, A Life’s Work, I encountered a passage that gave me pause. She had, she wrote, “the gloomy suspicion that a book about motherhood is of no real interest to anyone except other mothers...And even then only mothers who, like me, find the experience so momentous that reading about it has a strangely narcotic effect.”

She continued: I say other “mothers” and “only mothers” as if an apology: the experience of motherhood loses nearly everything in its translation to the outside world. In motherhood a woman exchanges her public significance for a range of private meanings, and like sounds outside of a certain range they can be very difficult for other people to identify. If one listened with a different part of oneself, one would perhaps hear them.

I have often found the literature around motherhood—to be or not to be—alienating. Cusk’s introduction distilled one of the reasons why. Here, she explicitly states the belief that countless essays, novels, newsletters, panels, forums, and conversations imply: The experience of parenthood, and the portal of birth, is so monumental that it wedges a permanent, immovable, and even spiritual divide between the people who give birth and undertake parenthood versus the people who don’t. So much so that there’s hardly a point in describing the phenomenon at all. After all, the childless among us lack the ears even to “identify,” let alone understand or empathize with their experiences. I have generally felt suspicious of this belief, as well as the assumptions underlying this belief. As social animals who frequently share our personal experiences with one another in order to better understand experiences that are not our own, I have never grasped why, exactly, this capacity would cease to function precisely at the experience of birth and, by extension, parenthood. And anyway: Where, exactly, did I fit in Cusk’s formulation? I was not eligible for the “mother” category, who Cusk said were the only people likely to read the book; yet I didn’t neatly fit into her non-mother category, a group she said would have no interest in, and no ability to perceive, what she tried to describe in her writing. Again, I found myself lacking the right words to describe my position. I was not a “mother;” nor was I a father or parent of any kind. In the language of birth classes and pamphlets, I was a birth partner or birth support person. In shorthand, I was a friend to someone who gave birth. Even auntie or chosen family, terms I gladly embraced, didn’t quite encompass my role. In terms of specificity, each of these options left something to be desired.

My life is full of relations for which I don’t have exact names—for which I do not have concise labels. Was this a problem? Initially, I found myself tempted toward the argument that better terms are needed. To say I’m a “friend” or “roommate” to someone—these terms didn’t convey the depth of our relationships, nor did they accomplish what I needed in particular moments this year: immediate recognition of our priority to one another. In recent years, books, podcasts, and articles have pored over the subject of friendship. It’s not hard to see why. Leaving aside the cursed polyamory discourse—a torment beyond the scope of this blog—I’ve enjoyed this genre of friendship-focused writing and thinking well enough. But as I observed myself jump to “we need better names” as a way to understand my own personal relationships, I started to wonder about what is gained and lost by the idea of “making sense” of complex relations. Much of the current writing around friendship expresses dissatisfaction with the word’s vagueness, demanding a clearer understanding of what friendship is, exactly, and what it’s for. “We lacked a name for the kind of friendship we have,” Amintou Sow and Ann Friedman wrote of their own relationship in the introduction to their 2020 book, Big Friendship: How We Keep Each Other Close. “Words like ‘best friend’ or ‘BFF’ don’t capture the adult emotional work we’ve put into this relationship. We now call it a Big Friendship, because it’s one of the most affirming—and most complicated—relationships that a human life can hold.” In The Other Significant Others: Reimagining Life with Friendship at the Center, author Rhaina Cohen wrote about close friendships that are not neatly categorizable—what she calls “platonic partnerships.” Cohen asked: “What exactly is this kind of friendship and what does it mean that people today find it difficult to understand it?” In my own case, the problem of understanding exactly what friendship is, and what to call it, has mattered most when it came to legal recognition (benefits I might receive if I were married to a person rather than just a friend) or work (adequately communicating why I was out of office). In a recent column for The Washington Post, Cohen argued that many of the legal benefits given married people should be extended to friends or other types of partners. She’s right and to that extent, clear names and labels have their place. But as I thought about it, I realized that I'd been confusing two distinct impulses: the need to explain matters to a system of power, and my own need to understand, to make sense of my own life.

“I want to tell you about the homes that I made mine and about the ones that made me,” wrote Vanessa A. Bee in her 2022 memoir, Home Bound: An Uprooted Daughter’s Reflections on Belonging. She quoted the Nobel Lecture given by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, who won the literature prize in 2017: “In the end, stories are about one person saying to another: This is the way it feels to me. Can you understand what I’m saying? Does it also feel this way to you?” Bee reframed the question to describe her own work: “This is the way home feels to me. Does it also feel this way to you?” Bee’s response presents an alternative to Cusk’s theory of parenthood and, implicitly, of storytelling. In Cusk’s formulation, people and their relations are slotted into neat categories (mother or non-mother); language and storytelling can do little to cross the borders of those categories, or promote comprehension between the people relegated to either category. For Bee, language is something else entirely: not just a logical tool, but a living invitation to description and even mutual understanding. Who is L. to you? so many people asked me this year. Who is M.? I often meandered, digressing into stories: the two months I shared a bed with M. because I couldn’t yet afford my own sublet; the week I built a picnic table with L.; the summer M. and I spent working in a library, pretending to be adults. Each time, I tell it all differently. The very namelessness of these relationships prompts me to describe them through the experiences, feelings, and habits we share, through the ineffable something that keeps us caring for each other. I enjoy living in this nameless place with these people. It focuses me on the truth, rather than the names, of what we are to one another. This is the way it feels to me…Does it also feel this way to you?

BLUE SKIESPeople are stampeding onto Bluesky at an incredible rate, having presumably fled the encroaching clutches of Twitter. Please follow Flaming Hydra here, as well as the Flaming Hydra Starter Pack of Hydra contributors. The Bluesky user experience is excellent, especially the thrilling “nuclear block” feature, which hides everything you say from the target goon and vice versa. Conversation over there now is lively, convivial, and algorithm-free. (Speaking of Twitter, you might consider deleting your tweets before November 15th, because after that they'll be used to train AI and there is no opt-out provision.)

Forward this newsletter freely! Subscribe, donate, jump around, touch yr. toes, you’re supposed to get up and walk around every twenty minutes.

|