Out With a Bang: Enforcers Go After John Deere, Private Equity BillionairesAt least for a few more days, laws are not suggestions. In the end days of strong enforcement, a flurry of litigation is met with a direct lawsuit by billionaires against Biden's Antitrust chief.It’s less than a week until this era of antitrust ends. And while much of the news has been focused elsewhere, enforcers have engaged in a flurry of action, which will by legal necessity continue into the next administration. One case in particular angered some of the most powerful people on Wall Street, the partners of a $600 billion private equity firm called Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR). But before getting to that suit, here’s a partial list of some of the actions enforcers have taken in the last two weeks. The Federal Trade Commission

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

The Antitrust Division

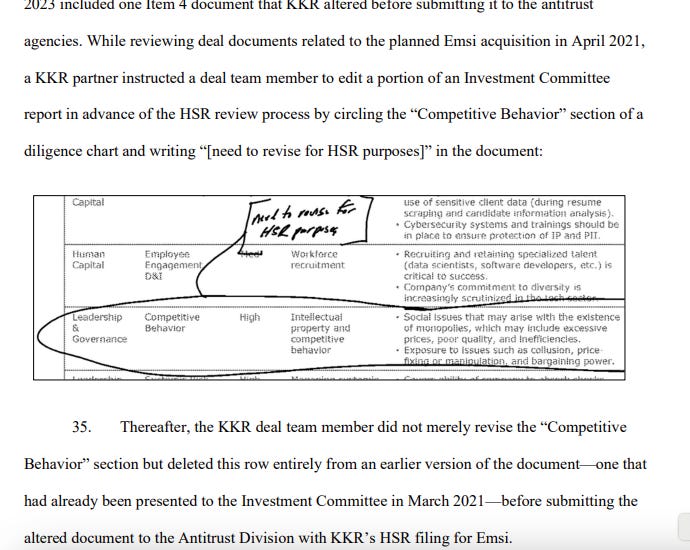

And honorary mention goes to the Department of Transportation for suing Southwest and fining Frontier for ‘chronically delayed flights.’ But the sparks actually flew when the Antitrust Division, under the acting Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust, Doha Mekki, filed a complaint against KKR for misleading the government over more than a dozen acquisitions, by withholding or altering deal documents they were required to file. And then KKR, spurred by orthodox Bush/Obama-era antitrust counsel, immediately counter-sued Mekki in her official capacity, accusing her of filing this case merely because she dislikes private equity. The reason these actions matter is because they are now in the courts, and the incoming administration will have to, like it or not, manage the casework. For some actions, like the PBM report release and the rule barring , the actions are bipartisan. For others, like the John Deere right-to-repair lawsuit, Trump’s incoming FTC Chair Andrew Ferguson issued a stinging objection to bringing the case. Yet, while there is likely to be some backsliding on antitrust enforcement, it won’t be a return to the days of Bush/Obama. On John Deere, Ferguson probably will carry it forward, but if he doesn’t the suit was brought along with Minnesota and Illinois enforcers. More importantly, the days of libertarian control of policy are over. This week, Attorney General nominee Pam Bondi in her confirmation hearing gave a nod to antitrust and the incoming replacement for Kanter and Mekki, a respected lawyer named Gail Slater. So what about this case involving KKR? KKR is not just another random private equity fund, it is in many ways the granddaddy of the entire industry, spawning multiple highly “respected” billionaires. The company was founded in 1976 and grew to legendary status in the 1980s, part of the whole Michael Milken-inspired wave that transformed Wall Street and corporate American through mergers fueled by junk bonds. KKR was characterized most famously in the book Barbarians at the Gate over its purchase of RJR Nabisco. Today, the fund owns everything from a roll-up in dentistry to cheerleading monopolist Varsity Brands the book publisher Simon & Schuster, which it bought after a judge blocked a merger with Penguin. It’s not all bad; KKR is apparently doing a good job with the publisher, I’m told by my friends in that industry. Still, they clearly don’t like anti-monopoly laws; KKR’s annual report lists antitrust as a risk, going over the litany of Biden enforcement priorities, and concluding with “The increased scope and vigor of antitrust enforcement could impact our business, the investment activities of our funds and the valuations and businesses of our portfolio companies.” The specific law KKR allegedly violated is the Hart–Scott–Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, or HSR law, which mandates that companies engaged in mergers above a certain size notify the government and hand over information about the combination. The Antitrust Division’s allegation is that KKR withheld or edited documents they were required to submit on at least 16 different acquisitions in 2021-2022, during a massive merger wave spurred by Covid-era Fed stimulus that overwhelmed antitrust enforcers. In some cases, like the $6.9 billion acquisition of Applovin, KKR just didn’t file a form before it closed the deal. In others, like its purchase of labor market analytics firm Emsi, its employers deleted sections suggesting that the deal could be monopolistic. While it seems technical, the point of the HSR form is to make the government aware of corporate combinations so it can investigate, instead of being in the dark. This law was recently updated, and the antitrust agencies in 2023 put out a new form asking for more information, which I described in a piece titled “Government Stupidity is By Design.” That’s the first significant update to the form since 1978, and it is being contested by the U.S. Chamber and private equity trade associations. But this lawsuit is about the old form, which still has lots of language with inclusive scope, stuff like merging parties must send “all studies, surveys, analyses and reports which were prepared” by or for officers to evaluate market shares and competition. By refusing to submit documents in accordance with the law, KKR exhibited a culture of bad faith noncompliance. The specific acquisitions KKR is alleged to have screwed up include purchases of Emsi, Lynx, Ross, OutSystems, Barracuda, ERM, Kobalt Music, John Laing, Therapy Brands, Equus I, Equus II, Neighborly, Applovin, Adjust, and Minnesota Rubber. It may not just be a civil claim; Bloomberg reported in October that there’s a criminal investigation of KKR as well. So how strong is the evidence? It’s pretty good. As the DOJ put it, "one KKR employee who omitted and altered multiple documents from an HSR Act filing described KKR’s approach to its premerger filing obligations: ‘I’ve always been told less is more 😊.’” In response, a more senior executive replied, “I believe in less is more too….” In the complaint, there is even a picture of a handwritten note on a deal doc. In that graphic, a KKR partner circled a part of an investment doc on “competitive behavior” and “monopolies” and wrote that it needed to be revised “for HSR purposes,” aka to prevent the government from seeing it. Withholding documents from investigators is a big no-no, the kind of process foul akin to kicking sand in the eyes of the umpire because it prevents them from doing their job. And the rhetoric from DOJ is blistering. “KKR’s rinse-and-repeat failures to provide complete and accurate information about its mergers and acquisitions were systemic,” said Mekki. “Through document omissions, alterations, and failures to report deals, KKR threatened the integrity of the Division’s premerger reviews and, in some cases, obscured the market impact of its deals and serial acquisitions.” So what was KKR’s response? It was, to understate it, aggressive. KKR immediately countersued Mekki personally, alleging that the Antitrust Division was nitpicking on a few “inadvertent, alleged paperwork errors” that were “not in any way an intentional attempt to circumvent antitrust review,” and did not end up mattering anyway as a pretext to attacking an industry and all of American business as Biden people head out the door. Essentially, none of the deals were litigated, so why should anyone care? Moreover, the rules themselves, via guidance documents of the FTC, are confusing. “Seasoned practitioners who specialize in HSR filings,” wrote KKR, “including the sophisticated law firms that advised KKR—are left to rely on a web of informal FTC opinions to navigate rules that are confusing, internally inconsistent, and riddled with exceptions.” (One wonders why PE trade associations are suing to prevent an update to these oh so confusing rules, but I digress.) KKR lawyers argued that Mekki, and Biden enforcers who didn’t even sign the complaint, like Jonathan Kanter and Lina Khan, bear “hostility towards mergers and acquisitions involving the private equity industry” and have “little regard for legal precedent and antitrust law’s historic focus on consumer welfare.” It’s an interesting and personal dig at Mekki, who worked under the Trump administration, but it makes more sense when you realize the brief was co-authored by Reagan antitrust chief Charles “Rick” Rule, who does appear to feel personally attacked by the change in antitrust enforcement. But there’s likely rage among KKR billionaires as well, because this suit tarnishes their brand. KKR is a trendsetter and one of the great brands in PE, and seems to be a safe place for any reputable pension fund to place money. Many people throughout the private equity world, for four decades, got their training at KKR. So the Antitrust Division’s suit is taken as a statement of outrageous behavior by enforcers, an insult to the great men who made the industry what it is. Kristi Huller, KKR’s media rep, sent me a statement on their countersuit: “We took this action reluctantly. We and our founders have managed our firm for 50 years by choosing to do what is right over what is easy. It is our hope that an independent arbiter might facilitate a more fact- based—and less political—approach.” Ok, all that being said, are these really just paperwork fouls? I don’t think so. Several of the deals at issue look questionably legal. For instance, KKR didn't submit required information to the government showing that their acquisition of Emsi - a labor market analytics firms - would lead to price hikes and monopolization, since they already owned a competitor, Burning Glass.

In another example, KKR submitted only four documents when its subsidiary Atlantic Aviation, a fixed-base operator for general aviation (aka private jets) bought a rival, Lynx, withholding twenty nine other documents it should have submitted. In those omitted documents, KKR wrote that the merger ‘“will help increase rates” in the Pittsburgh region and “will help lift rates and prices” in the Portland region.’ It’s not clear why these deals weren’t challenged. I suspect KKR was just trying to jam through obviously illegal deals in the 2021 and 2022 merger wave, when they knew antitrust enforcers just didn’t have the resources to go after all of them. As one industry source told me at the time, “Once the major brands, Signature, Atlantic, Million Air move in, they do their best to raise handling fees (especially in the smaller regional airports where there is typically only 1 FBO per field) and fuel costs.” If it’s true that KKR was trying to disguise deals its partners thought might be illegal, then that’s a no-no. But there’s more that suggests bad faith. KKR executives allegedly mislead their *own* lawyers when withholding documents from the government. And KKR execs continued to withhold and edit documents to the government even after they were told they were under investigation by the government for doing just that. KKR's outside counsel themselves were, according to these allegations, complicit as well, in possession of documents that the DOJ sought, but they wouldn’t provide. It’s an ugly set of allegations, and it definitely feels like the kind of suit that would change the industry, if it goes through litigation. But will it? And more broadly, what happens to most of the cases filed by this group of enforcers? The answer is not at all clear. The Trump Antitrust Division could just settle the case. And on this particular complaint, the judge assigned is a corporate-friendly Biden nominee Jennifer H. Rearden, who in private practice worked for Uber against people with disabilities, landlords accused of discriminating against people with HIV, and on behalf of Chevron to have environmental lawyer Steven Donziger punished. Rearden, by instinct, is likely to side with KKR, though with judges, you never know. But more broadly, there is a huge overhang of litigation in the courts for Trump enforcers to deal with, and much of it is with more sympathetic judges. Many of these cases, though not all, have state enforcers as fellow plaintiffs, which means they can’t just be settled on the say-so of Federal officials. But even if they could, I don’t know that they would be. Ferguson, for instance, did issue a dissent on the John Deere right-to-repair monopolization claim. But that was mostly process-oriented. Actually pulling back on the suit, and upsetting farmers, carries different costs. So who knows? The only thing that’s clear is that the final week of this enforcement regime isn’t quite over, and a lot of big business CEOs are wishing it were. Thanks for reading. Send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or comments by clicking on the title of this newsletter. Or if you work for or adjacent to a monopoly and have interesting confidential stuff to share, go ahead and do that. If you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues of BIG, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |