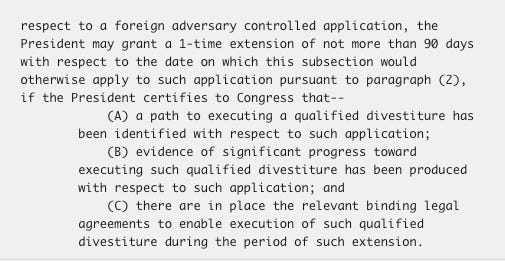

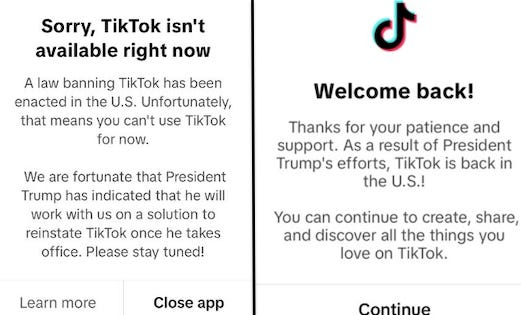

Monopoly Round-Up: Explaining the TikTok DisputeThe law never called for TikTok to be banned, it called for a divestment. So what's happening now? And what is China's role?The monopoly round-up has a lot of good and bad news, as usual. Lina Khan went all Scarface in her final days, Trump organized a cryptocurrency worth $25 billion just before he’s sworn in, and Walmart’s entire business model gets dinged in an important antitrust suit. But first, I want to discuss the biggest monopoly story of the day, which is TikTok going dark and turning back on. There’s a lot of hot air on the topic, and discussions about the policy and politics of social media. What’s missing seems to be a clear explanation of the law itself. In this post, I’m going to explain the law that Congress passed, the Supreme Court decision ratifying that law, the Chinese government’s interest in the situation and Trump’s decision. What has happened over the past five years vis-a-vis TikTok is an important chapter in our ability as a society to engage in self-government. And there are very useful lessons to take away, regardless of what happens. I’ll start with the pro and con side of the TikTok law. The pro-side of the law goes as follows. A few months ago, I ran into a former TikTok employee at a bar at night, and we got to talking. This guy, call him Calvin, told me about how creepy the internal operations of TikTok are in terms of privacy and lurid material, and how he encountered specific operational documents in Chinese that the company explicitly sought to have not translated. He was disillusioned, and said he thought that company officials routinely lied to American officials about how much was managed from China. Nothing he said was definitive, except for things I won’t repeat for fear of defamation. But let’s just say, TikTok is not trustworthy, and it’s not trustworthy in a way that goes beyond non-Chinese social media apps. TikTok can manipulate what Americans see in ways that we would never realize. It could help politicians China favors, or harm those it disfavors. It could manipulate information about foreign policy. There are an endless set of permutations involved here. The bottom line, though, is that TikTok is a Chinese corporation subject to Chinese national security and intelligence laws. If Beijing demands a change to the algorithm or access to overseas data, TikTok must comply. And that’s bad for America. The con side of the law is also compelling. For a lot of Americans who love and use TikTok, so what if there is manipulation? To them, U.S. national security concerns are not credible, the U.S. government is far more of a threat to their wellbeing than the Chinese government, it seeks to engage in propaganda as aggressively as anyone else, and more broadly, U.S. tech giants do everything that TikTok does, except they produce inferior products. On a practical level, hundreds of thousands of creators rely on TikTok for their livelihood, their political discourse, and their social lives. The U.S. government is intruding by censoring their speech by banning a platform just because it’s the national security deep state can’t control. So that’s the gist of the argument on both sides. But what does the law itself say? And is it about censorship? The backstory started a few years ago, after a great deal of concern over the expansion of TikTok in the United States. TikTok is a short-form video service, and was able to gain a foothold in America because precursors, like Vine, were killed by American big tech monopolies, and ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, had a protected home market in China, where most American tech giants are prohibited from operating. TikTok a better product than what Meta produces, as it has superior video editing tools and a more addictive algorithm. But it is also subject to Chinese laws that mean it must, according to the Supreme Court, “assist or cooperate” with the the PRC’s “intelligence work” and to ensure that the Chinese Government has “the power to access and control private data” the company holds. TikTok’s ownership by a foreign adversary ran straight into the traditional American approach to regulating media and communications infrastructure, which is that foreigners, especially hostile powers, are legally prohibited from controlling what we rely on. These kinds of restrictions go back to the Constitutional convention. As Alexander Hamilton said about attempts to ward off external influence, ”Foreign powers also will not be idle spectators. They will interpose, the confusion will increase, and a dissolution of the Union ensue.” In everything related to telecommunications law going back from the early 1900s to the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, foreigners, especially those from adversaries, are simply treated differently. For instance, even Rupert Murdoch had to become an American citizen to buy certain regulated media assets. Recently, the U.S. government forced the gay dating app Grindr to divest from Chinese ownership over fears of blackmail and coercion. Zephyr Teachout and Joel Thayer have a good amicus brief explaining the history. I wrote up the backstory in March, when the bill passed. In 2020, Donald Trump, as part of this tradition, issued an executive order under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act mandating a divestment of TikTok within 45 days to a non-Chinese owner, at which point it would be banned. But his order was struck down by a conservative judge on the legitimate grounds that the then-existing law prohibited the President from regulating the flow of information. Congress needed to act to give such authority. Congress would have to authorize action on TikTok. For several years, the Biden administration negotiated with TikTok, but couldn’t satisfy its national security concerns. Congress nearly acted several times over concern with China, but despite widespread concern, the GOP was worried Democrats might use expansive powers for censorship of conservatives, and Democrats felt that the conservative drafting of the law wouldn’t pass Constitutional muster. As a result, Congress didn’t pass the law in final form until March of 2024, with some of the final holdouts expressing concern that the Chinese government might be manipulating views of the Israeli-Hamas conflict. So Congress passed a law mandating that TikTok be sold to someone who is not controlled by the Chinese state, which is considered, in the statute, a “foreign adversary.” You can read that law here. The penalty for refusing to sell the American TikTok is that it can no longer operate in the U.S. TikTok and many others have framed the law as a TikTok ban, but it’s really a divestment law, with a ban as a last resort. By 2024, however, Trump reversed his position. Whether the change was due to TikTok generating support for his candidacy, or one of his big donors Jeff Yass owning a stake in ByteDance, or some other reason, it was a significant shift. So what does a divestment mean? A “qualified divestiture” means the app is no longer controlled by the Chinese state. But it also has implications for the technology as well. There can not be “any operational relationship” involving “cooperation with respect to the operation of a content recommendation algorithm” between the new firm and a ‘foreign adversary’ controlled operation. You can’t sell TikTok U.S. but keep using the Chinese controlled algorithm, because Congress made it clear that the Chinese state controlling what Americans see was not ok. The law specifically named TikTok, but also applies to other applications as the President determines, though there is an appeals process. And there’s a strict timeline. 270 days after its enactment, TikTok must either be sold to a buyer that is not controlled by the Chinese government or it must shut down in the United States. That deadline hits today, at which point app stores will face legal liability if they allow the distribution of the TikTok app. After the law was signed, TikTok had 270 days to sell its U.S. operation. But it refused to consider doing so. There were multiple potential buyers for this valuable property, but the Chinese government prohibited any sale, using its authority over the algorithm, which it subjected to export controls as a valuable technology that cannot fall into the hands of foreigners. That said, despite the 270 deadline, in the law, there’s also a 90 day extension the President is able to offer if he thinks that there is a path to divesting the app. The specific section is as follows: During the 270 days, TikTok and a bunch of creators went to the courts, arguing it is an unconstitutional abridgment of their free speech rights. The Supreme Court on Friday ruled against TikTok. It’s a very important case, not just for TikTok, but because it was part of a series of cases - such as Citizens United and NetChoice - attempting to prohibit government regulation of important industries through an expansive reading of the First Amendment. Google et al were hoping the court would suggest that a corporate divestment or regulation impacting expressive behavior would become unconstitutional. Fortunately, the Supreme Court allowed government regulation of the ownership of communications platforms, as long as such rules don’t explicitly implicate what is being said and are reasonably tailored. The court has not “treated a regulation of corporate control as a direct regulation of expressive activity or semi-expressive conduct,” and “we hesitate to break that new ground in this unique case.” To draw a metaphor, the government can regulate microphones, just not what people say using them. Regardless of what you think of TikTok, it’s an excellent ruling for those concerned with the power of tech platforms. All that being said, the initial 270-day deadline is today. As a result, Google and Apple stopped letting TikTok be downloaded from their app store, and TikTok itself went dark and sent users a message when they logged on the app. Then, 14 hours later, TikTok turned back on, offering a different popup message. Basically, TikTok said it is subject to a law banning the app, and praised Donald Trump for somehow thwarting that law. In truth, Trump just said he’d offer the 90 day extension that’s in the law itself. Trump, for his part of this ordeal, said he will use an executive order to give TikTok that reprieve, and focus on cutting a deal to keep the app functional. “The order will also confirm that there will be no liability for any company that helped keep TikTok from going dark before my order.” He also said he wants the “United States to have a 50% ownership position in a joint venture. By doing this, we save TikTok, keep it in good hands and allow it to say up.” Much of the political world exploded, musing on whether this whole episode was a ‘win’ for Trump. Some politicians, like Chuck Schumer, said they’d like to soften the TikTok law itself, while others, such as Tom Cotton, said the law will still be in force. In the meantime, a variety of suitors have lined up to buy or merge with TikTok, such as Frank McCourt, Jeff Bezos-backed AI firm Perplexity, and rumors of Elon Musk or Steve Mnuchin leading a coalition of Saudi money. Regardless, Donald Trump is clearly heavily involved in dealmaking here. And that brings us to the Chinese government, which has veto power over whether TikTok gets sold, because it can block the sale of the algorithm. Xi Jinping cannot afford to lose face in letting Trump force a divestment of TikTok U.S. without getting something in return. Trump has expressed a desire to go to China, and may be interested in cutting a broader deal involving not just TikTok, but trade, economics, cybersecurity, farm commodity sales, semiconductor sales, and perhaps issues like protections over Taiwan. In his first term, he cut such a deal, in which China committed to buying an extra $200 billion of U.S. products. Unfortunately China didn’t follow through, but Trump likely thinks he has more cards to play this time. TikTok might just be one part of this broader arrangement. It’s possible Trump brokers the sale of the accounts, data, and brand without the recommendation engine, but that opens up difficult operational questions, and is likely still in violation of the law. Trump tends to mesh public and private interests to get things done, so I suspect whatever resolution is likely to be messy. Regardless, it’s cleanest legally if the whole thing gets sold. If not, Trump is in a weird spot after 90 days, because he will be openly refusing to enforce a detailed law. Of course, Congress could always change the statute. Or TikTok could still be banned. What does happen if the ban kicks in? If TikTok gets prohibited, then, as happened in India when there was a ban, Meta and Google will likely benefit most. Most people won’t really care after a month or two, as it’s not a particularly hard technology to reproduce. More broadly, TikTok, as well as Meta and Google, were all in serious trouble for for violating laws around tracking children, and Meta and Google also face antitrust suits. And there has been useful progress in rolling back the lawlessness of data brokers in terms of selling sensitive information. So the TikTok law is best understood as part of the attempt to regulate social media markets in general. Ultimately, saving TikTok will require either convincing Congress to allow China to keep controlling it, Trump to simply not enforce the law, or a broader deal between the U.S. and China. There’s a lot more to say about TikTok, and the politics of the divestment/ban. But I thought I’d offer what isn’t really out there in the reporting, which is a description of the law itself, the court case, and the implications for media regulation going forward. And now, after the paywall, the rest of the monopoly news, including an absolutely insane series of crackdowns on corporate America that made into the courts just before Trump takes office. As I said, Lina Khan went full Scarface. The details are on the flip... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |