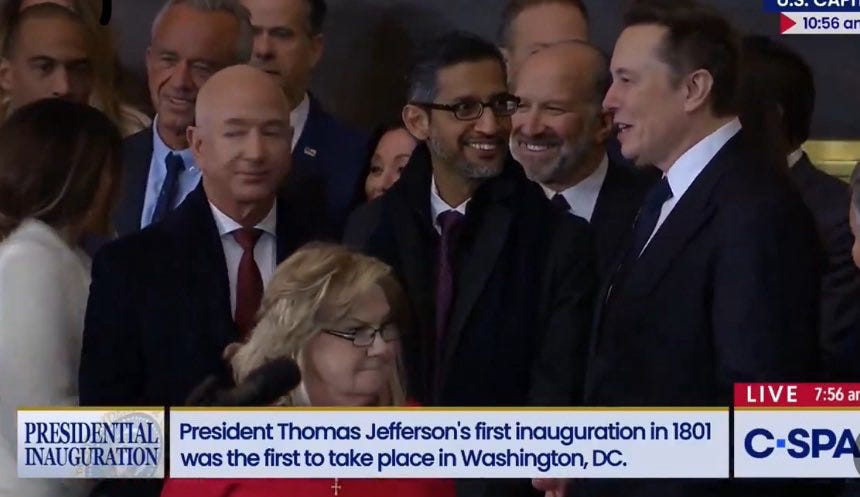

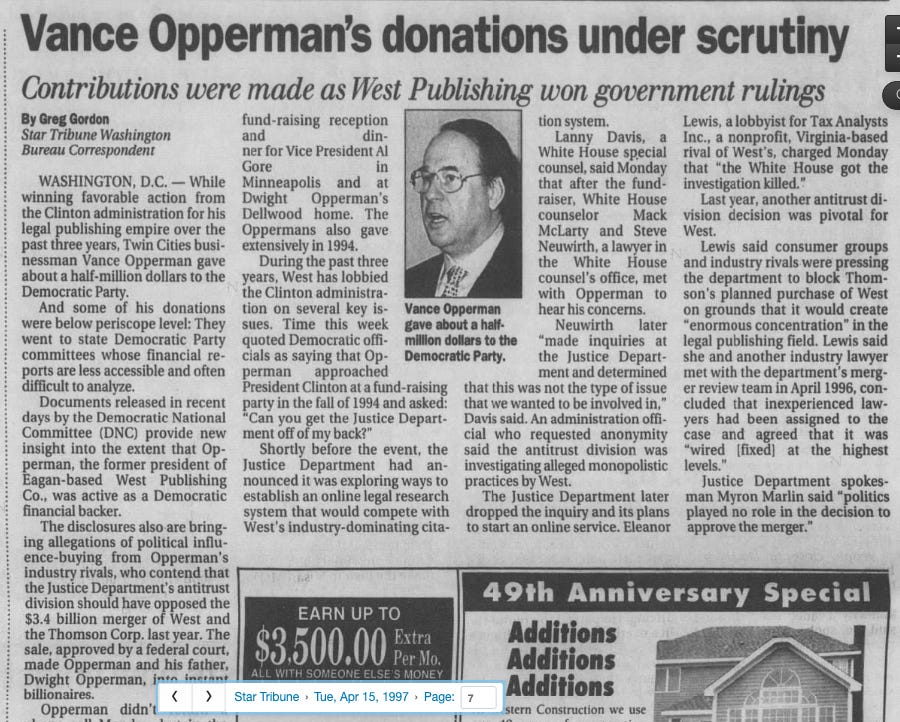

Antitrust in an OligarchyTech executives started gaining power under Bill Clinton, and haven't stopped. How does antitrust law work in a society run by billionaires and foreign governments?The first time Trump took power, in 2017, the resistance was quite annoying. The monopolists aligned with the Democrats and said to Trump, ‘Yes you are rich but you are not in our club.’ This time, they are seeking to lock arms with Trump, which is why big tech billionaires had a special seating arrangement at the inauguration on Monday. With a flurry of executive orders out the door, it’s clear that this time, Trump is organized and has a coherent vision of how to run the government. Is the symbolism of the inauguration a signal of coming policy choices on antitrust? Certainly, that’s the consensus. CNBC is broadcasting interviews with happy private equity executives from Davos, and there’s a sense of overwhelming joy from dealmakers who think that Trump will foster more mergers. This morning, Pepsi’s CEO Ramon Laguarta publicly praised the Republicans on the Federal Trade Commission for opposing the Robinson-Patman Act lawsuit last week, suggesting he thinks that the company is going to get out from under the law. There’s a hope that flattery and donations can lead to the end of pesky antitrust cases. The Washington Dulles airport runways were full of private jets ferrying people to and from the inaugural festivities, and there are rumors that the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, will be involved in everything from buying TikTok to taking over Intel. There are other rumors that Trump is seeking a broader deal with China. Here is the Wall Street Journal editorial page making the point with the subtlety for which it is known. At the same time, there are indications of overconfidence on the part of the superrich. The new acting chief of the Antitrust Division, Trump official Omeed Assefi, according to Bloomberg, did a video message to the department in which he “praised the work of the Biden Administration under antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter, and pledged to continue with the aggressive stance going forward, according to one of the people. There will be no “relaxation” of enforcement, he said.” There are other hints. Tucked away in one of the new executive orders was a demand to “eliminate unnecessary administrative expenses and rent-seeking practices that increase healthcare costs.” Still, these are just hints, a reading of tea leaves. So what does all of this mean for antitrust enforcement? Well, the short answer is I don’t really know. But I have three observations. Antitrust Is Here to StayFirst, antitrust enforcement is not going away. Trump and Republicans want to use this law for a variety of purposes. They dislike pharmacy benefit managers, and may want to keep the cases against PBMs going. There is a significant overhang of other complaints, against everyone from Google to Visa to Agri-Stats, and while settling them all would be a logical thing to do if Trump were a libertarian, it’s not clear how he thinks about this area. So who knows what he does? Also, antitrust is a body of law that’s designed for business leaders to fight with one another. Elon Musk is suing Microsoft, OpenAI, Reid Hoffman and Sam Altman for antitrust violations. Microsoft’s CEO testified against Google in the case against Google’s search monopoly. Fubo sued Disney/Fox/Warner Bros over a sports streaming joint venture. A bunch of conservative Republican state attorneys general are going after Blackrock for a conspiracy in which they forced coal companies to cut output and raise prices. Just rolling back antitrust enforcement in a blanket way, versus settling specific cases, seems unlikely. Antitrust Is a Dealmaking WeaponSecond, decision-making around antitrust cases will become opaque and overtly politicized, instead of by line prosecutors deciding to bring cases. While there’s always some politics involved in enforcement choices, there has been a norm that one should at least pretend to enforce the law in a neutral manner. That norm is likely gone. We’ll see a lot of deal-cutting, or rather, we won’t see it, but it’ll be happening, behind the scenes. Trump will negotiate over TikTok, or LIV Golf and the PGA Tour, or the Amazon cases, or whatever, in return for concessions he seeks. You’re not supposed to do that, the Tunney Act was passed in the 1970s to give judges a say over corrupt settlements. But it’s 2025, and Trump sees himself as a deal-maker. I don’t see why antitrust would be exempt from that. Now, to be clear, this observation doesn’t mean the old system was good, it just means that some of the ways it seemed untoward will be different. The way to corrupt that old model was to drop cases entirely. Biden antitrust enforcers were actually squeaky clean and neutral, but the old consumer welfare adherents were not. To take a random example, in 1997, Bill Clinton got his Antitrust Division to drop a case against the merger of West and Thomson - creating the overpriced Westlaw system - in return for a a half million dollar donation to the Democratic Party by Vance Opperman, the owner of West, who asked Clinton at a fundraiser “Can you get the Justice Department off my back?” That indeed happened, and West “soon thereafter won a $14.2 million contract to provide Justice with online legal research.” That example is a pretty consistent illustration of how corruption in antitrust worked from the 1980s onward; the first episode of Organized Money was about the corrupt scheming that led the Obama administration to drop the antitrust case against Google in 2012. One way to understand the oligarchy that is cementing its control over American society is that they owe their success to the lax antitrust policies of Reagan, Clinton, Obama, and Bush. That’s how venture capitalist Marc Andreessen explained it in an interview in the New York Times, anyway. There was an unspoken deal that Democrats had with tech oligarchs, Andreessen said, that they could basically do whatever they wanted without any interference, as long as they paid taxes and were nice liberals. That deal ended under Biden, which took an anti-crypto and anti-consolidation stance. The Reckoning for Democrats Is HereAnd Andreessen’s point leads me to the third observation, which is that anti-monopoly policy could become a more important part of politics for the Democratic Party, which will create some awkward dynamics, as most of the party leadership was elected during the oligarch-friendly tenure Andreessen describes. On a procedural level, there are Democratic state enforcers who have antitrust authority and are co-plaintiffs in cases brought by the Federal government. And there is interest in holding the line against attempts to settle those cases on the cheap. Some state enforcers may pick up the slack in challenging mergers, like the Capital One-Discover deal, that everyone in the capital markets assumes will go through. On a political level, Democrats are deeply unpopular and lack any sort of confidence. The Obama model failed. The Biden model failed. Their social issue claims failed. Their foreign policy approach failed. What else do Democrats have to offer other than economic populism? New York Governor Kathy Hochul has called for legislation to ban algorithmic rental price fixing. Philadelphia and San Francisco have already banned the practice, and Colorado may join them. Hochul is as corporate-friendly as you get in Democratic politics, so it says something that she’s engaged in this level of pandering. Moreover, many party members were radicalized by the image of big tech titans at Donald Trump’s inauguration, iconography revealing that Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Sundar Pichai, and Mark Zuckerberg paid $1 million apiece to secure political influence. But still, it’s awkward for party leaders who never really internalized the threat of oligarchy, growing up in a system run by Clinton and Obama. Here’s the likely next Chair of the Democratic National Committee, Ken Martin, making a cringeworthy distinction between “good” and “bad” billionaires, trying to navigate how much Democrats have come to hate “the tech-industrial complex,” as he puts it. All of which is to say that Trump’s policy choices this time could be much clearer than they were in his first term. He is the dominant politician of our age, and will create the contrast that allows for the creation of a new political agenda. Thanks for reading. Send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or comments by clicking on the title of this newsletter. Or if you work for or adjacent to a monopoly and have interesting confidential stuff to share, go ahead and do that. If you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues of BIG, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |