An 'always on' OpenAI device is a massive backlash waiting to happenIf the thing ever gets made, it will be like Google Glass all over again, but worseLast week, the big tech news was that OpenAI had acquired Jony Ive’s design studio in yet another deal worth so many billions of dollars, to build some vaguely defined “AI devices.” While the announcement itself was void of meaningful information about the apparently forthcoming products, details of OpenAI’s plans and what the they’re supposed to look like soon started leaking out. As those details leaked, basically all I could think about was how much people are going to hate these things. If an OpenAI hardware product ever does launch, there’s going to be plenty of, let’s say, rather justified hostility towards them. An OpenAI-branded device might make the public vitriol spewed at the Google Glass—which was banished by backlash for a decade—tame by comparison. <BLOOD IN THE MACHINE is 100% reader-supported and made possible by my excellent paying subscribers. I’m able to keep the vast majority of my work free to read and open to all thanks to that support—if you can, for the cost of a beer a month, or, uh, a Nintendo Switch game a year, you can help me keep this thing running. On top of that, you can access the Critical AI reports, a short installment of which you’ll find at the bottom of this article. That’s a perk for paid supporters, and today, we’ll wade into artists taking the fight to AI in Sweden, the self-driving trucking boom, and a study that reveals AI is terrible at therapy. Thanks everyone, for all you do. Onwards./> According to the Wall Street Journal, Altman told OpenAI staff that the incoming device won’t be a phone or glasses, but that it will be portable and always on, to gather data about its users’ environment, and, of course, that it will be a phenomenal success: Altman said it will add $1 trillion to OpenAI’s value. He also said that the products, which he referred to as “companions,” will ship by the end of next year, and that they will sell them “faster than any company has ever shipped 100 million of something new before.” The supply chain analyst Ming-Chi Kuo, meanwhile, reported that according to his research, mass production is expected to begin in 2027, and that

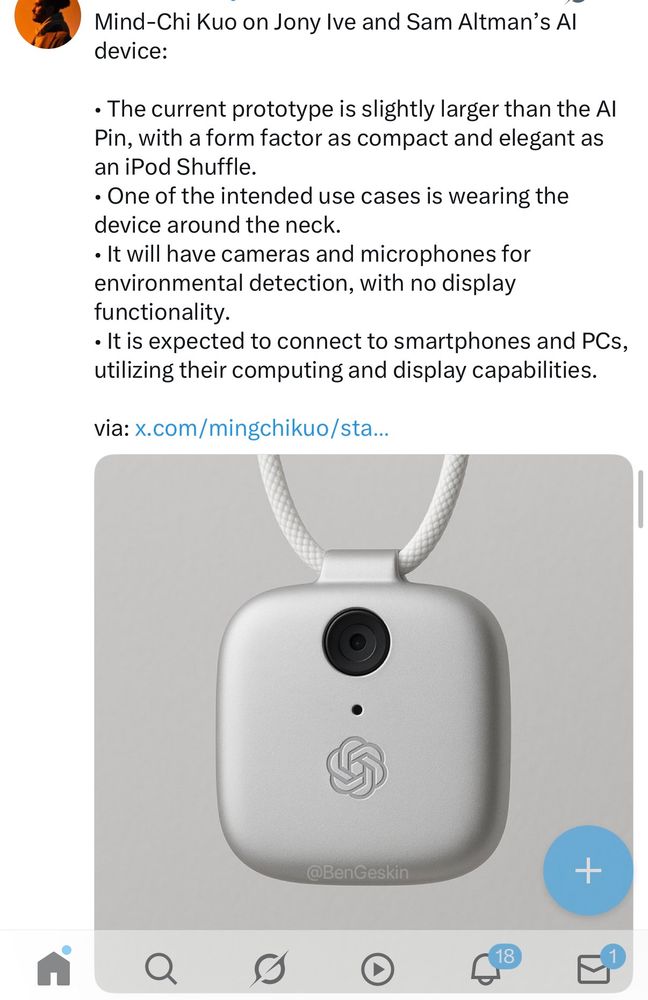

The self-described AR/VR/AI Content Creator Ben Geskin made an AI-generated design mockup using the above details, which looked like this: Obviously, this is not a rendering of the final product, or even a prototype of the product, it’s one guy on social media sharing an AI-generated image (which, humorously, he watermarked). But it’s effective enough at conveying what an always-listening, always data-collecting OpenAI device would be, so it’s been passed around social media a good deal since. Surprise, people hate it. I’m a little disappointed this doesn’t have a shock collar  Tue, 27 May 2025 12:12:11 GMT View on BlueskyFor good reason: well, this is what silicon valley is cooking up

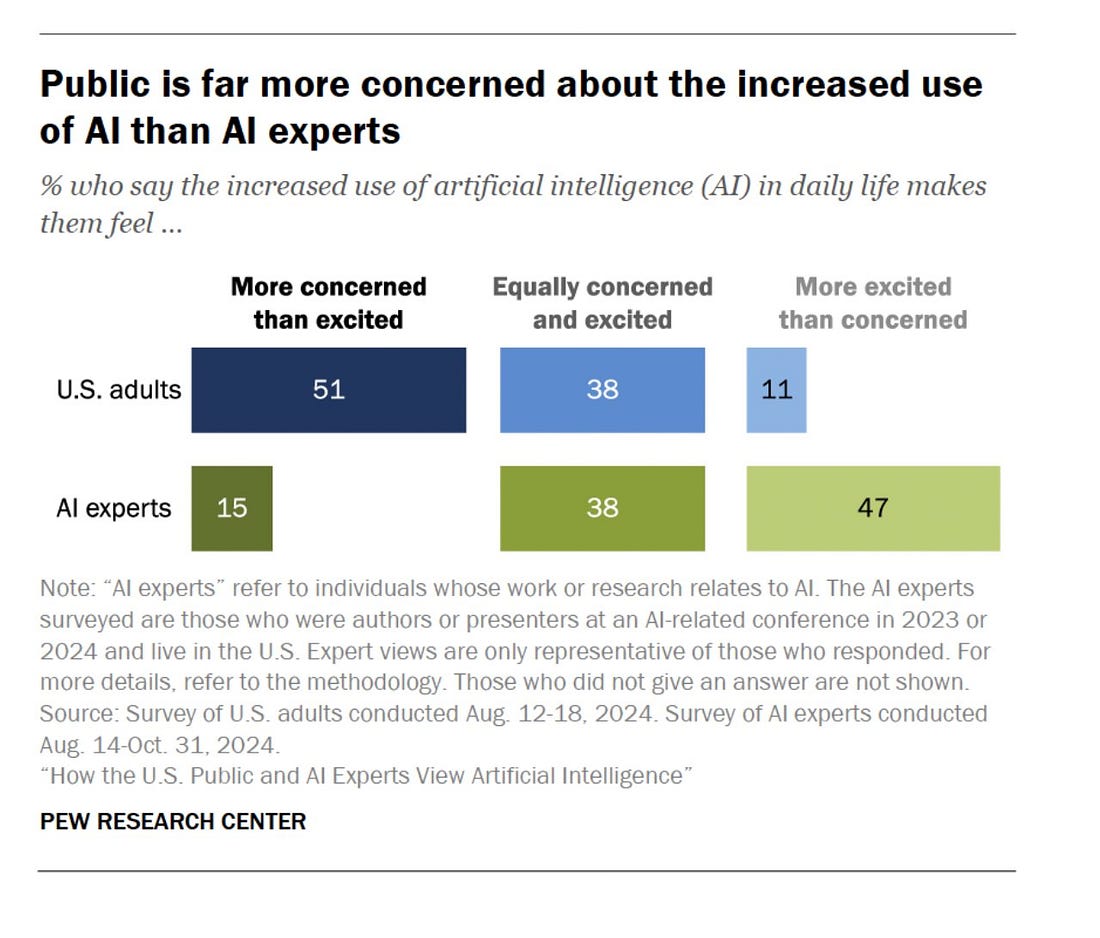

a device that's always on. so when a user goes about their life talking to people, everyone who comes within a certain capture radius will have their data (raw and natural conversation data) enrolled  Fri, 23 May 2025 11:53:04 GMT View on BlueskyNow, this is still mostly speculation; some reports are saying it will be worn like a necklace, others that Ive doesn’t want it to be a “wearable,” others just that it will be a “third device” in addition to your phone and computer etc etc etc. But given what we do know—that it will always be on to receive data—and will necessarily contain instruments to collect that data—microphone, camera, sensors— it is safe to assume that it will be a surveillance machine of considerable proportions. So that’s one strike against it right out the gate, and a valid reason for people to reject its very premise; ChatGPT collects user input to train its models already, now just imagine that everything you hear, see, or say becomes training data owned by OpenAI. If you’re old enough to remember the debut of Google Glass in 2013, then you’re old enough to remember one of the most pronounced bouts of public backlash against a tech product in the 21st Century. Early users of Google Glass—the search giant’s augmented reality glasses—were dubbed Glassholes and endlessly mocked on social and regular media. In particular, people recoiled against the idea of normalizing a device that allowed them to be photographed or documented against their will. The device flopped among developers and early users, too, and that public outcry, and the sense of utter rejection of Glass it stamped into popular culture, basically banished the very concept of such a device for nearly a decade. A lot has changed since then, of course. There’s a case to be made that courtesy of other “always on” devices like Alexa, Ring, and a decade-plus of total smartphone saturation, public tolerance for mass surveillance and tech company-orchestrated privacy violations has been chipped away. Then again, sometimes we just need a blunt reminder of how bad things have gotten to get angry all over again. Notably, Google had been involved in a number of privacy-violating scandals in the run-up to Glass’s launch, which the glasses then crystalized; the device, in other words, also became something of a beacon for the discomfort, distrust, and ambient anger people had at Google in general. It’s very easy to see the same happening to OpenAI. And remember, Google wasn’t particularly unpopular in 2013. People had privacy concerns, but Google still carried its don’t be evil aura, and Silicon Valley was widely seen as a beneficent engine of progress. It’s a different landscape today, and a very different story with OpenAI and AI products more generally. Poll after poll finds that the public is more concerned than excited about AI. There’s a widespread distrust of Sam Altman and OpenAI. And, perhaps most importantly, there’s a sustained anger at the very foundations that the modern AI industry is built on. There’s anger among artists, writers, creatives, and other workers at the way AI systems were built on their work without consent or compensation, at the way AI output is being used to degrade their livelihoods, at the way AI companies have benefitted at their expense. There’s anger over the growing energy, water, and resource costs of powering the AI systems. There’s anger among the AI safety crowd at the way the major AI companies are developing consumer products without guardrails or accountability. There’s widespread anger over the specter potential job loss. There’s a lot of anger. Throw a bunch of OpenAI-branded pendants—or orbs, or AI iPod shuffles, or whatever it ends up being—around early adopters’ necks, and my guess is you’ll see another serious round of public shaming, of what you might call AI-generated Glassholing. The stakes are higher; we’re not just talking about privacy, which is of course very important, but often not as viscerally felt as threats to people’s livelihoods. And there are a lot of people who would no doubt see OpenAI device users as gleefully wearing their contempt for others around their necks. This is a recipe for mass backlash, in other words. Look, the thing could be total vaporware—we might hear a couple updates on io progress from Altman here and there before it fades away, the announcement alone having done its part to keep the AI narrative rolling. It could also launch and be laughably awkward and bad, with the most obnoxious people you can imagine repeating questions too loud in the restaurant to the hunk of plastic strapped to their necks, and thus go the way of the reviled Humane Pin—which Altman also invested in, recall—all on its own. I doubt Altman and Ive launch something that sucks so obviously overtly, they’d probably rather not launch at all. So if the thing comes to fruition, then we really might see users boasting OpenAI pendants in the open, embracing their a roles as a consumer avatars of technological inequality, as proud real-world AI influencer blue X checkmarks. In that case, well, in a world where Google’s Waymos are coned and torched, where Tesla dealerships are firebombed for what they stand for—well, things might get interesting. In this context, it’s also important to remember that backlashes are often not only well-deserved, but hold the potential for political and social progress, too. The successful pushback against Glass, as writers like Rose Eveleth have argued, helped establish boundaries for what rights we were willing to cede to tech companies. “Google Glass is a story about human beings setting boundaries and pushing back against surveillance,” Eveleth wrote for Wired, “a tale of how a giant company’s crappy product allowed us to envision a better future.” Looks like we’re going to need to tell a story like that again pretty soon. The CRITICAL AI REPORT: Artists take a hard line against AI, the brewing self-driving truck crisis, and why AI should never replace your therapistIt’s not all grim news out there—artists and workers are banding together to fight for their livelihoods, and finding legally binding ways to push back on big AI. One example:... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |