Synergies: When Customer Service Signs Off as 'Joseph Stalin'Primo Brands is the child of Nestle, Danone, and Suntory, a roll-up of water delivery companies and bottled water brands. I've rarely seen the internet hate a company more.In 2022, Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” to describe the process whereby an online platform degrades in quality after acquiring market power, moving from an enjoyable place to spend time into an extractive experience. Doctorow’s term took off, not just because it’s a little naughty, but also because it describes something we’re all experiencing on a regular basis. Enshittification was initially meant to describe what’s happening with online platforms, but people regularly use it to describe all parts of our economy. And there’s a reason for that. Over the past couple of months, several readers encouraged me to look into a company called Primo Brands, America’s number one seller of bottled water, or in its own corporate-speak, “healthy and sustainable hydration solutions.” A little less than half of its business is delivering water jugs and coolers to homes and offices of affluent consumers, the rest is selling water in retail outlets and supermarkets, as well as restaurants.

I’m writing about Primo Brands because I rarely encounter a company with as much online hatred from its customers and employees as this one. The corporation has an F rating from the Better Business Bureau, there are multiple bitter threads on Reddit where company employees anonymously beg for someone to sue their own company, and even on anodyne announcements on LinkedIn, angry commenters chime in. Obviously not everything on the internet is true, but what is written online is consistent with multiple frustrated customers who told me about similar experiences. And when I put up a Twitter request for info, I got multiple responses within just a few minutes. One customer even sent me a note from a customer service representative who signed off on a cancelation request under the name “Joseph Stalin.” I’m not kidding. Here’s the note.

Now, there’s a slight chance that the person’s name really is “Joseph Stalin Y,” though I doubt it. I asked the company if they employ anyone with that name, they wouldn’t say. More likely it’s black humor from a self-aware customer service representative, akin to an old Friends episode. There are many ways to define a monopoly, from the ability to raise prices without losing customers, to certain market share levels imparting the ability to exclude rivals. I’m not sure it’s foolproof, but I’m guessing there could be a market power problem if your customer service representatives are impersonating genocidal dictators, even as a joke. How does a water cooler delivery service come to have such corporate representatives? And are there larger implications? Well, let’s start with the business itself. You may not recognize the name Primo Brands, but there’s a good chance you know some of the brands it owns or controls. Over the last twenty years it has purchased all the big domestic spring brands: Poland Springs, Arrowhead, Saratoga Spring Water, Mountain Valley, Zephyrhills, Sierra Springs, Crystal Springs, Crystal Rock, Deep Rock, Alhambra, Deer Park, Hinckley Springs, Ice Mountain, Ozarka, Pure Life, Sparkletts, and Pure Flo, among others. As billionaire Dean Metropoulos, who put the company together, said in November at an investor conference, “We control all the spring brands in the U.S. across the country.” While a publicly traded company, Primo Brands is, as S&P noted, controlled by two large private equity financiers, One Rock Capital and Metropoulos & Co., who own 57% of the stock value. Metropoulos is a well-known investor in the food and beverage space, buying and then selling Hostess with its iconic Twinkie brand, and owning such firms as Bumblebee tuna, Pabst Blue Ribbon and Morton Salt. Primo Brands’ most important line of business is delivery, which went under the name “ReadyRefresh” (though it has other names as it merges other companies with their own services). While it has a direct line to millions of customers, it also goes through retailers. If you order Costco home water cooler service, you’re buying from Primo Brands. Home Depot, Walmart, and Lowes also resell it. Bottled water is a competitive market, but water delivery is less so. Here’s bond analysts at S&P making that point. I bolded the relevant part.

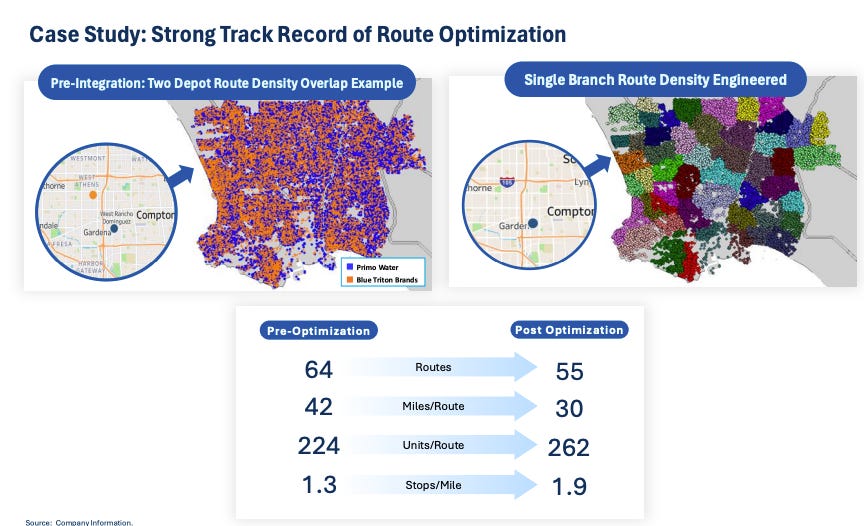

In other words, water delivery is quite profitable. In 2003, the Wall Street Journal reported that supplying water coolers to homes and offices delivered margins of up to 60%, and there’s no reason to think the margins have gone down since then. Now, it’s hard to imagine that delivering jugs of water could foster monopoly or even have significant barriers to entry. But according to the architect of the company, it does. “We're building a business that's very, very unique,” Metropoulos said. “Its infrastructure cannot be displaced. Its brands cannot be displaced.” So what are those barriers? Delivering water to homes and businesses is a network service. Like portable toilets, propane tank refills, garbage pickup, or package delivery, it gains efficiency when its trucks can serve more customers per route. As Joe Wiggetman, Chief Customer Officer put it, “As more households adopt a large format water, we build greater route density, making our distribution network even that much more efficient.” The brands are also iconic and difficult to replicate. Customers who like water delivery do so because it’s a premium product, from domestic natural springs. Primo Brands has permits and the legal muscle to pump spring water from 90 different springs all over the country. Water is also heavy, a large case of heavy water doesn’t travel cost efficiently. So it requires a lot of distribution infrastructure - depots, factories, distributors, retail outlets, exchange rack for five-gallon bottles, and self-service refill stations, dispersed nationwide. Cycling an empty bottle, cleaning it, and refilling is a scale business. So we’re talking tens of thousands of refill and exchange locations, three million direct customers who get deliveries, springs nationwide, and hundreds of thousands of retail outlets. Its executives also stress as one of its advantages that it is vertically integrated, meaning that its facilities for refill or bottling or delivery can only be used by Primo Brands product, which is the kind of self-preferencing at issue in certain big tech cases. It’s also useful that Primo Brands can reach 90% of the country, because it means national retailers have to deal with one company as a vendor instead of cobbling together a set of regional networks.. Retailers like being the distributor for Primo Brands because it can bring traffic back into the store when people bring back empty bottles. It’s hard to know what percentage of the national market is controlled by Primo Brands for a couple of reasons. The main one is that there is no real national market; water delivery is regional, so we’re talking city by city, town by town. And some places have local water delivery companies. Another problem with market definition is that there are competitors who offer similar but not identical services; Culligan, for instance, installs water systems and does some water delivery, though it mostly offers water filtration, which is not the same as spring water. The company itself wouldn’t give me market share data. “We don’t disclose those publicly,” wrote someone who signed off as “the Primo Brands team.” The most powerful argument against Primo being a monopoly is that it faces a powerful competitor everywhere - the faucet, along with various systems like the Brita filter. That said, people buying this kind of service don’t want to drink tap water. In fact, according to Primo Brands, 88% of Americans drink bottled water, and 18% of Americans will only drink bottled water. As you would expect, the company is encouraged by recent distrust in tap water. Here’s Metropoulos, to investors, on one “tailwind” for the company: “Whether it's on television or in the headlines, toxic lead found in majority of America's tap water across the country, that isn't going away, and everybody's very concerned about it all across the country and actually across the world.” The following slide from their February investor day emphasizes the point the “Wellness” trend, with its rootedness in distrust of public systems, is helpful marketing. The best data on market shares in this space is from reporting on the bevy of mergers over the years. Primo Brands is a merger of the water subsidiaries of food giants Nestle, Suntori, and Danone, in a complex interplay of corporate roll-ups and private equity that took place over the last fifteen years. It started with Nestle. From the 1980s to the 2000s, Nestle bought up a host of domestic bottled water brands (Arrowhead Water, Deer Park Spring Water, Ice Mountain, Pure Life, Splash, Saratoga, Ozarka, Poland Spring, and Zephyrhills). Nestle took about a third of the home delivery market as of 2015. The “close second” was DS Waters, which was the joint venture of Suntori and Danone that formed in the early 2000s. Once people start subscribing to a water service, they probably don’t switch often, so the market share numbers likely haven’t changed that much. But who owns them does. Over the course of the next ten years, Nestle’s water business and DS Waters were rolled up as part of other mergers, and then, in 2024, they merged with each other. The details of that decade of acquisitions are tedious. Nestle sold its US. water business to private equity in 2021, naming the now independent business Blue Triton. In 2024, Blue Triton merged with Primo Waters, which had bought DS Waters ten years earlier, when it was named Cott. There were also many other deals: DS Waters-Hillcrest (2013), DS Waters-Splash (2013), Cott-DS Waters (2014), Cott-Aquaterra (2016), Cott-Mountain Valley Spring (2018), Cott-Primo Waters (2018), Primo Water-Highland Mountain (2022). The point is, it’s likely that the end result is Primo Brands has at least 65% of the home water delivery market, if not more, though that’s assuming the market hasn’t changed that much since 2015. There are a few other reasons I suspect market power at work. Primo Brands executives are sort of bragging about market power, in their own way, to investors. Here’s Jeff Johnson, Chief Transformation Officer, in 2024, saying Primo Brands will save a lot of money because the two companies that just merged “have depot locations in the same cities, neighborhoods, and even streets.”

Here’s the slide, which is map of the change in delivery routes in Los Angeles. It appears to be shutting down head-to-head competition, which is a pillar of the 2023 merger guidelines. Primo executives showed another map to investors describing overlaps of Blue Triton and Primo Water facilities. They were discussing what they can shut down to help save money, but it’s useful in helping identify areas likely to have significantly elevated market power. Glancing at this map shows overlaps in metro areas around San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston, Chicago, Omaha, Indianapolis, Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, New York City, Albany, Hartford, Providence, Boston, Orlando, Miami, Tampa, Jacksonville, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Charleston, Washington, D.C., and Phoenix. So far, on recent earnings calls, executives have not suggested they are driving substantial price hikes. They are talking about raising margins via hundreds of millions of “synergies,” which is to say, cost cuts. Executives are telling investors that these cuts are coming from increased efficiencies, like denser routes, better IT, and so forth. In a competitive market, such cost cuts would theoretically be passed through to customers in the form of lower prices, and I haven’t found evidence of that happening. It’s also likely that the quality of the service is declining, as the company is undertaking layoffs of customer support staff. I heard from multiple customers that when they try to switch from Primo Brands because they can’t get anyone on the phone to schedule a refill, there are often no direct alternatives. I spoke with Steve Hunt, who does member support for Costco, and he told me that he recently noticed a “huge influx” of complaints about Primo Brands from Costco customers. Decreased quality is its own form of price hike, because customers are paying the same amount for a worse service. In some ways, the market power of any water delivery service is about switching costs. Customers themselves are locked into the service, similar to a software platform, which allows for the high margins the Wall Street Journal discussed. Today there are a litany of complaints about Primo Brands - the app not working to reschedule deliveries, bad customer service, promises to refill water that are never kept, impossibly long hold times to get on the phone, and deceptive billing. Employees are posting anonymously on Reddit about the firm’s market power, bad service, hidden fees, and coming price hikes, as well as “AI generated scripts” they are supposed to read to angry customers. Here’s one post: I asked Primo Brands about this customer service issue. They sent me a note on complaints about the quality of their customer service, saying they were “aware that certain customers have been experiencing disruptions in their delivery service” and were working “with them to resolve these issues as quickly as possible.” They blamed upgrades of “facilities, routes, and technology” for the disruptions. I don’t want to discount it out of hand, maybe the bad customer service is temporary, so I’ll post the full note after my signature, and you can see their explanation. It does seem that executives understand they have customer service issues. Deutsche Bank analyst Steve Powers actually asked CEO Robbert Rietbroek about it, and Rietbroek gave a similar answer to the one I got. I wanted to know why Powers asked the question, but he didn’t respond. Neither would the former CEO of Primo Water. My guess is that they aren’t particularly concerned about legal repercussions, because they likely force customers and employees to sign arbitration agreements restricting their ability to sue. I asked if they use arbitration agreements, they wouldn’t say. (It’s notable that the Supreme Court is slowly rolling back this protection for corporations.) BIG is a reader-supported publication on monopoly and finance. If you are not yet a paid subscriber, please consider becoming one. We invest in finding out the truth. And yeah, that costs a few bucks, but in the long run it’s much cheaper.While drawing firm lessons about this situation would require more evidence, I would point to a few tentative conclusions. The first is that we need to find a way to make sure that employees have more power over their companies, whether that’s more unionization, putting workers on the boards of companies by statute like they do in Germany, letting them vote on mergers, or some other organizing principle. Customer service representatives do not like being yelled at, and if they had some power to fix the situation causing that dissatisfaction, they probably would. The second is that antitrust law is too permissive. Over the last fifteen years, there were many mergers that could have been stopped, but the law as it’s read now only allows blocking the biggest ones. That’s a problem - the monopolization started in its incipiency in the early 2010s, and should have been blocked there. But even when there was a big merger between Primo Brands and Blue Triton in 2024 - the Federal Trade Commission didn’t challenge it. And it’s not like it was a leadership willpower issue, Biden enforcers were historically tough. Agencies are understaffed, so it could be a resource issue. There are about the same number of FTC employees as there are guards at the Smithsonian museum, around 1,200 to manage consumer protection and antitrust in a $30 trillion economy. Yet at the time of the big merger, they were dealing with merger litigation against Kroger-Albertsons, the Novant hospital merger, and gearing up for a Temper Sealy/Mattress Firm challenge. It’s rare to have the FTC litigate a few cases a year, here were three cases litigated by the same division of the commission. They may not have had time to look in depth at a merger for affluent people that like bottled water, as well as businesses and gyms. Still, there’s no real reason for the resource limit; if Trump can increase the number of ICE agents by 10,000, why can’t Democrats add 10,000 antitrust enforcers? Unfair methods of competition cause at least as much harm as anything else in America these days. Finally, I’d say that we should eliminate arbitration agreements so that individuals can vindicate their own rights through class action lawsuits. If the complaints against Primo Brands are accurate, then there’s a case that this company is violating its contracts with customers en masse, secure that it doesn’t make economic sense for an individual customer to bring an water delivery complaint to arbitration. Allowing the public access to the courts as a collective class would restructure the market in a way that creates the right incentives for a company like Primo Brands. And it would reduce the importance of government enforcement, offering more certainty to business people. I don’t want to overstate the situation here, so without speaking to Primo Brands itself, it’s worth noting that every example of a degraded service contributes to a sense of powerlessness and frustration within America, a sense that things are only going to get worse. That’s why Doctorow’s word enshittification took root. Hopefully we can flip this situation on its head, and eventually it will become necessary to invent a word that means the opposite. Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. cheers, Matt Stoller Here’s what Primo Brands sent me about their customer service issues:

This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. |